Полная версия

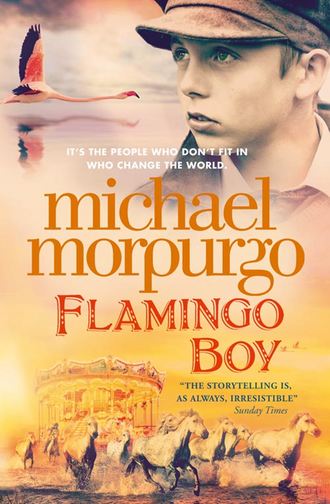

Flamingo Boy

As you will hear, Nancy was later to become like an aunt to me – or more like a fairy godmother, I sometimes think. She told me often that, when Lorenzo was born, it was the greatest joy of their lives. He seemed a healthy child, always cheerful and loving. But then, when he was about two or three, they began to notice that he did not seem to want to get up and walk like other children, but sat there, watching the world go by. He was often bewildered and agitated, inconsolable sometimes, and for no reason they could understand. Neither was he learning to talk as other children did. Whenever they went into town, to Aigues-Mortes, which they did every week to set up their stall to sell their produce, other stallholders and customers would begin to comment on their beloved Lorenzo. They were not being deliberately unkind, but from time to time they did say that Lorenzo did not seem to be like other children.

Becoming more and more anxious about him as the years passed, and upset by some talk in the town that was not so kindly meant, Nancy took him at last to the town doctor who examined him. He told her that Lorenzo was not developing as a normal child should, and informed her that there was an institution, in nearby Arles, for children like Lorenzo, where he could be cared for. When Nancy cried, the doctor simply said that these things happen, and that an institution was what would be best for the child. “Such strange and unnatural children,” the doctor told her – and she never forgot his words – “do not belong amongst normal people in normal society.”

These words, Nancy always said, stopped her tears. Anger stopped her tears. She told the doctor: “This is my child, our child, and he belongs with us.” She never went to see that doctor again.

At home, on the farm, Lorenzo grew up strong and happy, in his own way, at his own speed. He learned to walk – though he was never as coordinated as other children. His legs and arms always seemed too long for him to manage, and he found it hard to run, but grow he did. He grew and he grew.

“He shot up as fast as a sunflower,” Nancy told me once, “and just as beautiful too!”

Speech he also found difficult. But he loved to play with words, repeat them endlessly, rhythmically, whole sentences sometimes too, and he loved to sing, hum songs – words seemed to come easier to him when he sang them. Nancy and Henri soon realised he had a genius, a real genius, for imitating the sounds and movements of animals and birds, especially flamingos.

He loved above all else to be outside with Nancy and Henri on the farm. He was strong, so always happy to fetch and carry. He liked to feel useful. He would bring fodder and water to the animals, and loved to stay close to them, crouching down to watch them as they fed. Everyone noticed that horses, bulls, sheep, hens were always calm around him. The wildest of black bulls, the fiercest of the white stallions needed only to hear him humming, to feel his touch on their neck, his breath in their nostrils, and they were as gentle as lambs.

But it was the flamingos he loved to be with best of all. “Flam flam”, Nancy always said, were the first words he ever spoke. He would sit down for hours on end, in his favourite place – on an upturned rowing boat by the side of a lake – looking out over the island, just to be with them. His great treat as a little boy was to be rowed by his papa out to the island to be near the little flamingo chicks, watching them finding their legs, trying their wings. He would call to them and they would come to him. He knew instinctively how to tread softly, move slowly, be still amongst them, and become one of them. He loved them, and they trusted him.

Whenever he came back in the boat, Nancy always told me, he would run about the farm like a flamingo, honking as they did, imitating their run through the shallows before take-off, the spread of their great wide wings, the stretching of their necks in flight and then their elegant landing, his timing as perfect as theirs. Nancy told me once that when Lorenzo was being a flamingo he was at his happiest, that he became who he really was, his natural self.

And Lorenzo loved to ride. It was often the best way to get around the farm anyway, to move the bulls or see the brood mares, or to gather in the sheep, and, of course, to see the flamingos in the lakes all around. So whenever one of them went out on the horse – usually it was Henri – Lorenzo always had to go with him, whatever the weather, whatever the time of day. He loved to be up on that horse – Cheval, Lorenzo always called him – clinging on behind Henri, laughing and singing. Sometimes Nancy would be there too, all three of them riding together, with Lorenzo in the middle – rising and rocking to the rhythm of the ride.

But they could never let him go riding on his own. He wanted to, longed to, but they dared not let him – he could not balance well enough. He had tried, often, but had always fallen off. It angered him and frustrated him, and when he was like that he would start to shout, to hit his head with his hands, and storm about the place, in a fit of rage, sometimes for hours on end before he calmed down.

There was one horse, though, that he discovered he could ride. This is where I come into the story, and how I first met Lorenzo.”

CHAPTER 7

The Charbonneau Carousel

“Lorenzo and I first saw one another on a spring morning forty years ago. It was market day in the town square in Aigues-Mortes, and holiday time for the children in town. Maman and Papa and I, we had spent all the day before setting up our beautiful carousel, the carousel that Papa had made with his own hands. He had carved all the animal rides himself, and Maman had painted them in bright colours, all the colours of the rainbow. Papa was very proud of it, so was she, and so was I, and so were all our Roma family.

We always caused quite a stir wherever and whenever we arrived, our carousel in bits and pieces, piled up into carts behind us. Family and friends would all come along to help put it up. It is what we always did during the spring and summer months, Vincent. We travelled the countryside with our carousel. We would set up in a village maybe, or in a field on the edge of a town, anywhere they would let us. We were quite a tradition, I can tell you. Remember, Vincent, this was a very long time ago. There was no television, of course, no films either, or very rarely. Just the Charbonneau Carousel. We were the big attraction.

But this was the first time we had ever brought the carousel to Aigues-Mortes. It was Papa’s idea. It was the biggest town around, he said. Business would be good there, with plenty of customers, lots of children, who might come again and again to have a ride on the carousel. We could stay for a while maybe. Maman liked the idea, as he knew she would. Roma families like us, travelling families, generally we like to keep moving on. But Maman always wanted to stay in a place longer than Papa. We Roma, Vincent, we have a saying. We like to follow the bend in the road, to be free to go where we want.”

My heart leaped. I hadn’t told her my story of the old traveller and the policeman, and I so wanted her to know it now, that in a way it was following the bend in the road that had brought me here. But I did not dare interrupt her again. I would tell her later.

“So that’s why we came to Aigues. We found a place for our caravan in a field down by the canal, just across the water from the town walls, where the horse had grass to graze, and water to drink. Honey, our horse was called. Unfortunately, I was the one who had to look after her, see she was fed and watered, pick out her hooves, groom her. Honey was not at all sweet. Badly named she was. Très méchant, ce cheval! She had a wicked temper. I never liked her and she never liked me. But for pulling the caravan she was the best horse we ever had.

They let us set up our carousel in the square, under the shade of a great plane tree, close to the church and the cafés and the shops, right in the heart of the town. It was a perfect pitch for the Charbonneau Carousel. The town was busy, the people seemed friendly, and, as Papa had said, there were lots of children about, so the rides on the carousel were almost always full. On fine days, when the wind was not blowing, and the rain was not driving in, we did good business.

We stayed there in Aigues-Mortes, of course, to earn money – everyone has to do that, Vincent, as I am sure you know. But there was another reason why Maman in particular was happy to stay put in one place much longer than usual, as I was soon to discover. Now that I was older – Maman broke the news to me soon after we arrived in Aigues – she told me we would be staying in the town long enough for me to be able to go to school for a while, to learn to read and write. And Aigues, she said, seemed the perfect place for me to start school. I never liked the idea at all. But Maman was very determined. So on weekdays I found myself, like it or not, going off to school, along with all the other children in town. But more of school later.

After school, and at the weekends, I was still where I most wanted to be, working on the carousel in the town square with Maman and Papa. Papa turned the handle to make it go round. He was as strong as an ox, shoulders and arms as hard as wood. Maman took the money and played the barrel organ, and I helped the children up, and looked after them once the carousel was turning, making sure they did not fall off nor try to jump off while it was turning. But, best of all, I was the one who had to bring in the customers, tempt them in, and I had my own special way of doing it.

I always chose Horse to ride, because he was the most popular. I would jump up on to his back, and, with the carousel turning, I would shout it out all over the square. “Roll up, roll up for the Charbonneau Carousel! Come along, come along! Have the ride of your life: on Lion, or Tiger, on Elephant, or Dragon, or Bull, or on Horse, this lovely white horse from the Camargue! Roll up, roll up!”

Then Maman would play her barrel organ for a while to entice everyone in, and I would go on with my shouting. I would hang on to the pole, one-handed, swinging myself out, as Papa turned the carousel round and round. I would leap from ride to ride, whooping with joy, showing the whole town how much fun it was. I loved to show off. I could put on quite a performance, Vincent – you should have seen me! We were a good team, Maman, Papa and me. Some days it could be slow, but most days, especially on market days and weekends, we would soon have children queuing up for a ride, all of them impatient to have their turn, to be off.

In the darkening summer evenings, the carousel would be a blaze of colour and lights – providing that Papa’s generator worked. Sometimes it did; sometimes it didn’t. It was – how do you say this? – a bit temperamental, that machine. Everyone in the town loved hearing Maman’s barrel organ and watching the carousel going round. In the spring and summer of every year, the Charbonneau family carousel was the heart and soul of Aigues-Mortes, and that made me very proud.

But, much as the townspeople might have loved the bright lights and music and the fun of our carousel, there were a few who did not like us, who shunned us in the street. I was still young, and I could not understand why. It upset me greatly, and made me angry too. Maman told me to pay no attention, that this was just how some people were, and that I would have to get used to it, that there were kind people in this world, and nasty people. That was just how it was. But I never really understood any of this properly, not until I went to school.”

CHAPTER 8

Rousel Rousel!

“I never wore shoes in the summer, as all the other children did. And the clothes that Maman had made for me – the long red skirt I always wore – did not look like anything they wore. And I had long, straggly dark hair down to my shoulders. My hair did not look like their hair. Some of them would sneer at me, and say how poor I must be to live in a caravan and not in a proper house. Soon enough, though, I realised there was more to it than that. There were other reasons, deeper reasons, I discovered, for their hostility. I was Roma, a “gypsy”, to them. I was “gyppo girl”. I looked different. I had darker skin than most of them – and that was true, of course – but they said I was dirty, which I was not. It was also because I could not read or write as they could – which was true as well. That, after all, was why Maman had sent me to school.

Some of them just avoided me, looked the other way, or walked off. I could tell also that they were nervous of me, and I did not understand why they should be. I mean it was true that if someone taunted me, if someone picked a fight – boy or girl – I always fought back and I always won. I was good at fighting. Winning was my way to survive in that school, whether in fights or in races. I found I could run faster, jump further, stand on my hands for longer than anyone else, do somersaults and backflips better than any of them. But none of that helped me to make friends.

There were some children – and a few teachers too, sad to say – who made it quite clear they did not like having me in their school, or even in their town. When I told Papa and Maman about all this, both of them told me to be proud and ignore them. But it was hard for me to realise that so many of those children who loved riding on our carousel, whom I had often helped climb up on to Tiger or Horse or Elephant, had in fact despised me all along, and not just me, but Maman and Papa too, all Roma people like us.

I was glad we lived away from them, in our caravan outside the town walls, on the other side of the canal. But I never minded at all being in the town square, working on the carousel. I was so proud of it, of Maman and Papa, and anyway I loved the bustle of the place. I did miss my Roma friends and family, though. I was away from my cousins, who were really my only friends, with whom we so often travelled during the rest of the year. Until the day I met Lorenzo, I had no one in that town I could really call a friend.

As I said, it was on a market day in spring in the school holidays that Lorenzo first came into my life. The carousel was turning, the music was playing, the rides were full of laughing children, all enjoying themselves. I was enjoying myself – everyone was. I noticed then a boy jumping up and down on the far side of the square. Even far away, I could see he was in a state of high excitement, waving his arms and clapping with joy at the sight of the carousel. Then he was taking his mother’s hand and dragging her towards us. I was used to seeing children come skipping up to the carousel, begging to be allowed to have a ride. The music drew them in – like moths to a flame, Papa always said – and I could see that this particular moth, this clapping boy, was fluttering with frantic excitement. The next time I came round on the carousel, he was still standing there, watching as the ride slowed down, calmer now, waiting, waiting, as children often did for their favourite animal ride to come by.

But, when the carousel came to a stop, I could see he was not looking at all at Elephant or Dragon, or Bull or Horse; instead, he was gazing higher up, mouth open in wonder, at the dozens of flying pink flamingos that Papa had carved, and Maman had painted, which made up the frieze that crowned our carousel.

“Flam flam! Flam flam!” he cried, pointing up at the flamingos, clapping his hands and bouncing up and down, quite unable to contain his excitement. Some people were laughing at him, but he didn’t notice. He had eyes only for the flamingos. Other children were already climbing up on the carousel by now, choosing their animal for the next ride, and I was helping them up one by one, looking after them as best I could, telling them as usual to hold on tight, not to get off while the carousel was turning.

By the time I had finished doing all that, I could see this boy was becoming quite agitated. His mother was trying to encourage him to go for a ride on Horse, but he kept shaking his head and pulling away. “I can’t understand it,” the mother was calling up to me. “Lorenzo wants to get on – I know he does. He loves horses, but he loves those flamingos up there more.”

The boy was looking at me now and – don’t ask me how – I knew at once what he was thinking. I said to him: “Flamingos need to fly free, don’t they? You can’t ride them. They would not like it. But you could ride Horse. He would love you to ride him.” I was standing right beside Horse, patting the saddle, inviting him up. “He’s a kind horse, never bites or kicks, I promise. We could ride him together, if you like.”

He was unsure. He was still thinking about it. I held out my hand. After some moments of hesitation, and a nervous look back at his mother for reassurance, he reached up and took my hand. I helped him up, and settled him on Horse, showed him how to hold on to the pole in front of him with both hands. I mounted up behind him, and put my hands on his shoulders. By now, he was bouncing up and down in the saddle, longing to get going.

“He won’t fall off, will he?” his mother asked me. “You will look after him?”

“I will stay with him,” I told her. He turned to me then and gave me such an open-hearted smile, a smile of complete trust. I have never forgotten the warmth of that first smile.

“Renzo,” he said, tapping his head. “Renzo.”

Then he tapped mine. “Kezia,” I told him.

“Zia Zia,” he said. And that is what he has called me ever since.

I waved my hand high in the air, the signal for Maman and Papa to begin the ride, that everyone was settled and ready to go. She started up the music on the barrel organ – the first tune was always “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” – and then we were moving, turning.

I had one hand on Renzo’s arm now to reassure him. I felt his whole body tense, heard a sharp intake of breath, saw the white of his knuckles as he gripped the pole with both hands. He was letting out loud shrieks of alarm and excitement. After just one turn of the carousel, these shrieks had turned to peals of ecstatic laughter, screeches of joy. Within a few minutes, he was daring to hold on to the pole with only one hand, and was waving to his mother. He was not just sitting on Horse now, he was riding him, rising to the movement, and loving every moment of it. His mother was too. Every time we passed by her, she seemed to be enjoying it as much as he was, laughing with him.

“Val Val!” he called out to her.

“Val Val!” she echoed. I had no idea what they were saying. They had their own language, those two.

Then, all too soon, it was over and they were walking away under the trees, back towards the market stalls. He kept looking over his shoulder at me, skipping along beside his mother, hopping with happiness. I hoped that he would be back, that at last I might have made a real friend in this place. But then he was lost in the crowd around the market stalls and was gone. I looked for him day after day, after that first meeting on the carousel, but he did not come back.”

CHAPTER 9

Fly, Flamingo, Fly

“I was never more miserable than in the days that followed. At school, our teacher, Monsieur Bonnet – I still hate the sound of his name – was picking on me and punishing me continuously. He kept telling me in front of the whole class that I was an ignorant child, a stupid gypsy child, a wicked heathen child. In the playground, some of the children in my class – Joseph and Bernadette were always the ringleaders – began to gang up on me. They told me to my face that they had decided from now on that no one would speak to me, because I was a “gyppo girl”, who dressed in rags, they said, who couldn’t even read. They did not speak to “dirty gyppos”, they said. Joseph would grab at my skirt, and Bernadette would pull my hair!

There was only one teacher I liked, Madame Salomon. She would come over and talk to me sometimes when no one else would. She wasn’t my class teacher, but I wished she was. But then one day Monsieur Bonnet told us that Madame Salomon had left the school and would not be coming back. “A good thing too,” he said. “We don’t need her kind here.” I had no idea what he meant. Not then.

I ended every day at that school feeling I was utterly alone in the world. I begged Maman and Papa to let me stay home with them, to help them every day on the carousel, like I did in the evenings and at the weekends, but they were adamant. They had never learned to read or write, or to do their sums, they said, but the world was changing. Everyone needed school these days. The old ways were going, like it or not. Roma children had to learn just like other children, or else everyone would think we were ignorant. I had to go to school: that was all there was to it. I argued, I cried, I threw tantrums. Nothing would change their minds.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.