Полная версия

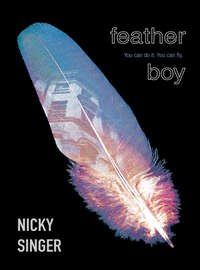

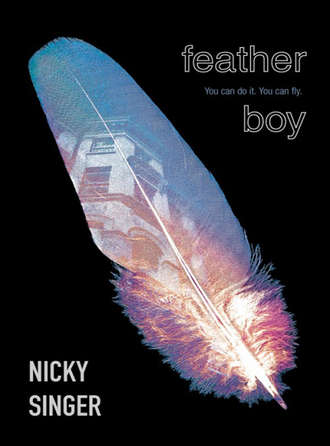

Feather Boy

I make my route decision the moment I let the back-gate latch fall. Click – I’m going to the sea. Click – I’m going past the Library. Only, to be honest, I do choose the sea more often than the other routes, because I love the sea. Especially in winter. Sometimes, when it’s really rough, the sea throws pebbles on to the promenade, and walking there is like treading on fists.

Today I choose the sea, but I don’t go as far as the prom, just down to the main road (where I stand a moment to look at the colour of the waves) before turning inland again. It doesn’t really matter which of the northerly roads I take, Occam, The Grove, St Aubyns, they all arrive pretty much at the gas works and then it’s just a few hundred yards to school. Today I select St Aubyns, which is a wide, ugly street with gargantuan four-floor buildings, most of which have now been turned into guest houses. One of them is called the Cinderella Hotel. It has a flight of ballroom-type steps up to its huge front door. And I’m looking, as I always do, for the glass slipper, when my eye is drawn to the building next door. It’s a colossal edifice, grim, square, semi-derelict. And, painted in gold on the glass above the boarded front door, are these words: Chance House, 26 St Aubyns.

I read the words and then I read them again. After which I shut my eyes, turn a full circle, and open my eyes again. The words are still there. As they must have been every one of the hundred times I’ve walked up this street.

“You can go there. Walk. It’s not far.”

And of course I know it’s Edith Sorrel’s house because it is precisely what I have been expecting. It’s the place I saw before I slept last night, the one I pretended to imagine. The one I knew was here but, perhaps, would rather not have known, which is why I suppose I chose to hear Edith Sorrel say “St Albans” when her clear-as-a-bell voice actually said, “St Aubyns”.

Do you sometimes feel drawn and repelled in the same moment? I call it the car-crash mentality – you don’t want to look but you just can’t help yourself. Even though you know you are going to see something appalling. Well, Chance House is my car crash. I’ve tried ignoring it but it won’t go away. So now I’m going to have to look. Worse than that, I’m going to have to go in, though every sensible fibre in my body is willing me to walk away.

There are two bits of good news. One is that I have to be at school in less than ten minutes. The other is that Chance House is boarded up. And I don’t just mean with a few nails and a bit of chipboard. Each of the eight-foot ground-floor windows has been secured with a sheet of steel-framed, steel-meshed fibreglass. The front door is barricaded with a criss-cross of steel bars, and although the second-floor windows are not obstructed, they are twenty foot from any hand-hold I can see. Of course it could be different around the back.

I look up the road and then down the road. No-one is watching. No-one I can see anyway. I slip into the shadow of the side of the house. Grass sprouts through the concrete paving. There’s a small door, set into the wall of the house about four foot above ground level. It’s not barred but it doesn’t look like it has to be. There are no steps to it, and as well as being overgrown with brambles, it’s swollen shut, rotted into its doorframe.

I advance, slowly, towards the back of the house, as if I’m scared of the corner. As if I expect someone to be lying in wait, just out of view. My heart pounds as I walk. But I can’t stop now. I come to the edge of the house, just one more step, I turn…

The garden is empty, overgrown. There are dandelions in the long grass. Bluebells and a smashed white-wine bottle. The sun is remarkably warm. I compose my breathing. There is steel mesh on the first window. And on the second. There is no way I will be able to get into the house.

And then I see it. French doors on to the garden. The mesh hanging free, ripped from the wall as if it were paper.

I don’t know who’s moving my legs but I’m going towards that open door. Walking fast now, past the dirty Sainsbury’s bag and the length of washing line, past the patch of scorched earth where someone has lit a fire. Of course if the door is open there will be people. Squatters, vagrants, drug addicts. Who knows? My heart’s back at it again. Bang, bang, bang. Like my rib cage is a drum. What am I going to tell these people? That I’ve come because some batty old lady asked me to? I should be creeping, slithering along the walls like they do in the movies. But I’m not. I’m walking with the boldness of the bit-part guy who gets shot. Somebody screams, and for a moment I think it’s me. But actually it’s a seagull, wheeling overhead.

My legs are still on remote control but there’s something wrong with my breathing. I seem to have lost the knack of it. I instruct myself to breathe normally. In out, in out. The ‘out’ seems OK, but the ‘in’ is too quick and too shallow. How long does it take a person to die of oxygen starvation anyway? In out, in out. I’ve come to the door. In.

In. The room has been stripped. There are brackets but no cupboards, the dust shape of what might have been a boiler, plumbing for a sink that isn’t there and a mad array of cut and dangling wires. On the left-hand wall is a rubble hole where a fireplace has been gouged out and the floor is strewn with paper, envelopes and smashed brick.

At the far end of the room is a glass door. An internal door which must lead to the rest of the house. I look behind me and then I step inside. The door’s closed but obviously not locked because someone has put a brick at its foot, to stop it swinging. A final look over my shoulder and I’m moving towards that door. But I’ve only gone a couple of paces when I hear the scraping. A rhythmic, deliberate noise that stops me dead. The sort of noise you’d make if you were watching someone, and wanted them to know you were watching, without yourself being seen.

Scrape, scrape, scrape. Pause. Scrape.

It’s coming from my right. From the small kitchen window over the absent sink. This window is almost opaque, darkened by the steel-mesh glass and the shadow of some bush or tree that’s growing too close to the house.

Scrape. Pause. Scrape.

I see the finger now. And the knuckle – which looks deformed. But perhaps that’s just the trick of the light, the refraction of bone through fibreglass. My heart is beating like a warrior drum. Tom torn torn torn torn torn. But I’m not going to panic. I’m emphatically not going to panic.

I panic.

I leap out of the room into the garden.

I scream: “I can see you!”

A holly bush continues to scrape one of its branches against the glass of the kitchen window. Scrape. Pause. Scrape. In time with the wind.

I’m so relieved I sob. Huge foolish tears rolling down my cheeks. Norbert No-Brain. Norbert No-Botde. At least Niker isn’t here to see. Or Kate. When the boo-hooing stops I look for a hanky. But I don’t have one so I pick a dock leaf and blow my nose on that.

Right. That’s it. I’m going back in. I make for the glass door. I stride there, kick the brick out of the way and go through into a thin corridor. Then I worry about the brick. If anyone sees the brick’s been moved, they’ll know someone’s in the house. I go back out into the kitchen (which compared with the corridor is light and airy and pleasant) and retrieve the brick. Then I discover I can’t shut the door with me on the inside and the brick on the outside. Or I can, just, if I squeeze my fingers around the gap between door and doorpost, edging the brick back into place. Hang on, what if someone jams the brick right up against the door, barricading me in? Change of plan. Better to have the brick on my side of the door after all. That way at least if someone comes in from the garden, they’ll knock it over getting into the house and I’ll hear them. I bring the brick in, lean it against the door my side. Now I’m safe. If the people are outside.

But what if they’re inside?

I look at my watch. Six minutes to nine. I really have to get to school. Absolutely can’t be late. Have to go right now. The skirting board in the corridor has been ripped off. There’s a gap between the base of the wall and the floorboards through which I can see down to some sort of basement. In the dark cavity there are flowerpots, lamp bases, lamp shades, a desk, a filing cabinet and a sink, the old ceramic sort. There’s also the sound of water. Not a small drip drip, but a gushing, the noise of a tap on full bringing water pouring from a tank. Or maybe a cistern filling, or a bath emptying or…

Crash!

It’s the brick. The brick has fallen. I wheel around, catch my foot in the hole in the floor, fall, twist my ankle, drag myself up, never once taking my eyes from the swinging door. But nobody comes through. Nobody comes through! Why don’t they come through! I’m not an impetuous person, but I burst through that door, hopping across the kitchen faster than normal people run. And then I’m in the garden, and actually my ankle’s all right, so I do run. Run, run, run – flowers, washing line, burnt ground, smashed glass, corner of house, swollen door, front wall. Front wall of Chance House. Safety of St Aubyns. I collapse on to the pavement.

“Run rabbit run rabbit, run, run, run.” A familiar voice croons softly above me. “Don’t be afraid of the farmer’s gun.”

I look up. About a hand’s breadth from my head is a pair of feet.

“Hello, Norbert,” says Niker.

He swings himself down from the wall.

“You want to watch yourself.” He brushes imaginary specks of dust from his trousers. “Bad place, Chance House.” He smiles.

“What?”

“Bad place, Norbert. Bad house. Bad karma.”

He looks at my blank face. “You don’t know, do you? Everyone in town knows. But you don’t.” He turns towards school.

“Niker…”

He pauses. “Yes, Norbert?”

“Tell me.”

“Please. Pretty please, Norbert.”

“Pretty please.”

He looks at me pityingly. “A boy died in there, Norbert.”

“What?”

“You heard.”

“What boy? Who?”

“Just a boy, Norbie. Pasty little thing, by all accounts. Fluffy hair. Pale. Pocked. Bit like you, really. But his mum couldn’t see it. Doted on him, apparently. Told him he was wonderful. So wonderful he could fly. So what does he do? Opens the window of the Top Floor Flat and gives it a go. Pretty nasty mess on the concrete by all accounts.”

“Top Floor? Top Floor Flat, Chance House? Are you sure?”

“You feeling all right, Norbert?”

“Niker, are you sure?”

“Higher the window, more the strawberry jam. Lots of strawberry jam in this boy’s case, Norbert. Top Floor Flat for certain.” He grins. “Come on now, bunny, you’re going to be late for school. Better hop it, eh?”

I remain sitting on the pavement.

“Suit yourself.” He turns away.

As I watch his retreating back, the little swagger in his step, I want to believe it’s all just a story. One he’s made up to frighten me. But I know what’s really frightened me is Chance House itself. You see, it smells like The Dog Leg. It smells of fear.

5

Let me tell you about Kate. She’s slim and has a small round face with a pointed chin and freckles over the bridge of her nose. Her hair is light brown and straight and she keeps it cut short, usually with a fringe. Her eyes are hazel and, when she smiles, a little dimple appears in her right cheek. Niker says she looks like a cat. She’s my idea of an angel.

It took me two terms to pluck up courage to invite her to my house. I chose a Friday, because that’s a day I know she’s normally free. Both times she went back with Niker it was a Friday.

“Thanks for asking, Robert,” she said. “But I can’t. I’m busy.” She smiled and I watched the dimple appear.

“Fine,” I said. “Another time maybe.”

“Sure.”

But I didn’t ask again. When someone says they’re busy, you never know if they’re really busy or just busy for you. And I thought if I asked again I might find out. And perhaps I didn’t want to find out. Besides it was clear I had left the door open. She could invite herself any time. But she didn’t.

So you can imagine how I feel when, next time we get onto the minibus to visit the Mayfield Rest Home, Kate chooses to sit by me. OK, so it’s not exactly a free choice. She’s late and there are only two seats left, one next to student teacher and damp sponge, Liz Finch, the other next to me. On the other hand, I have the seat over the wheel with the restricted leg room and Miss Finch has the front seat with the view. So if Kate’s just looking for somewhere to sit, Finch’s seat is closer and comfier. So I reckon it has to be significant that it is at my feet that she dumps her bag.

“Hi,” I say.

“Hello,” she replies.

I once set the dream alarm on Kate. Lay on my back in bed and asked myself how to make that dimple come more often for me. At 3 am I was dreaming that a boy was throwing stones in a lake. Every time he hit the surface it made a dimple. The water was radiating dimples. But the boy wasn’t me. I left it alone after that.

Hey – but who cares about the past? Right now Kate Barber is sitting next to me. The journey to the Mayfield Rest Home is ten minutes. I spend two of those ten minutes trying to open my mouth, which seems to have got stuck on closed. I want to say stuff like: did anyone ever tell you how insanely beautiful you are, Kate? But even I can see that’s nerdy, and I don’t want her opinion of me to drop from woodlouse to unicellular organism. So, after four minutes (Kate’s reading her book now) I say:

“Do you know anything about Chance House?”

“Sorry?”

“Chance House, twenty-six St Aubyns.” It’s not such a wild remark. Kate lives on Oakwood, which is just two roads from St Aubyns. “That big house that’s all boarded up?”

“No.” Kate returns to her book.

“Spooky. Spooky, spooky, creepy, spooky.” Wesley Parr’s face appears around my headrest. “Boy died in dat dere housie, Norbert No-Chance.” He looks at Kate. “Norbert No-Chance-at-all.”

“Oh, that house,” says Kate.

“Boy about your littlie, littlie age, Norbert,” says Weasel.

“So about your age too then, Weasel,” says Kate smartly.

“Oh creepy, creepy, bye, bye, spooky.” Weasel’s head disappears.

“So you do know?”

“Not really,” says Kate. “Or only as much as everyone knows. That a boy is supposed to have died there. And that it’s never been much of a lucky house since. Keeps changing hands.”

“Who was the boy?”

“I don’t know. It was ages ago, Robert.”

“How many ages?”

“Thirty years. Forty years. I don’t know. Why are you so interested anyway?”

“My Elder, Edith Sorrel. She lived there.”

“Oh right. Why don’t you ask her then?”

“Mm. Maybe I will.”

But of course I won’t. Can you imagine it?

Me: “Oh hello, Miss Sorrel, would you mind telling me about the boy who died in your house? I mean the one that fell out of the top-floor window? The plenty strawberry jam one?”

Her: (giving me that witchy look where she appears to be able to see right through me and out the other side) “No.”

End of conversation. But not end of story. Miss Sorrel picks up silver-topped ebony cane, bangs it three times on floor and kazzam! I’m a frog. That would be the happy ending. The miserable one would be the ending where…

“Robert. Robert!”

The bus has stopped. Almost everyone has got off.

“Robert Nobel, you are a dreamer.” Liz Finch is waving her hands in front of my face. She looks almost animated.

I pick up my bags and follow the others into the lounge of the Mayfield Rest Home. Today Catherine has arrived in advance of us. She has set up trestle tables with paper, paint, pencils, scissors, magazines and glue. The protective newspaper she’s laid on the carpet is already rucked up with the traffic of wheelchairs.

“Hello, hello,” she says. “Come in. Find your Elder, everyone. Sit down.”

There is a hubbub of greetings.

“Afternoon, Mr Root,” says Kate.

“Eh up,” says Albert.

“How you been, Dulcie?” says Weasel.

“What?” says Dulcie.

“Hi,” says Niker, tapping Mavis on the chicken-wing shoulder.

“Please explain,” says Mavis. “Don’t keep me guessing.”

“It’s me,” says Niker. “Me, moi, myself. Niker. Jonathan Niker. Double O one and a half.”

“Oh,” says Mavis. “Is that a poultice?”

“Could be,” says Niker.

“Sit down, sit down,” calls Catherine gaily. “Sit down by your Elder please, everyone.”

But I have no Elder. Edith Sorrel is not in the room. I remain standing.

“Sit down, Robert. It is Robert isn’t it?”

I sit.

Behind me Niker sets up a soft hum. Do, do der doo, do der do der do der doo. It’s a funeral march. “Never mind, Norbie,” he whispers. “I’m sure it wasn’t your fault.” Do, do der doo…

“Quiet now, please. Well, today I hope we’re going to move on to actually making some work,” says Catherine. “Some little illustrations of the wisdoms that we were talking about last week. I was speaking to Albert before you all arrived and he mentioned paths to me…”

“Primrose path to hell,” squawks Mavis.

“Right on,” says Niker.

“Well,” says Catherine, “I think Albert was thinking more of paths of wisdom. And path as visual image. Which I thought was a very good idea. Because paths are things that lead us on, take us from one place to another. So perhaps that could be our starting point for today. We might think of an individual paving stone, perhaps with a wisdom inscribed on it, or something growing round it, or something or someone treading on the stone… You can use any of the materials here and…”

People begin to drift towards the tables. In the noise and movement I slip away into the corridor. I remember exacdy where Edith Sorrel’s room is. Third on the right. I knock softly, in case she’s asleep. There is no answer. Quietly, I ease open the door. The room is small and institutional. There is a bed, a chair, a wardrobe, a basin and a bedside cabinet. Except for a toothbrush, flannel and soap, there are no personal items at all: no photos, no china, no knick-knacks, not even a book.

Miss Sorrel is asleep, breathing quietly and evenly. Sitting in the chair at the bottom of her bed is a man.

He rises, as if startled by me. He’s tall, white-haired and, despite the heat of the room, he’s wearing a full-length black overcoat. There’s something hunched about him, something glittering, that makes me think crow, hooded crow. He stares like I owe him an explanation, so I say:

“Hello, I’m Robert. I’m on the project.”

“Ernest,” he replies edgily. “Ernest Sorrel.”

“Oh,” I say. “You must be her brother then.”

“No. Not exactly.” His eyes bore into me. “I’m her husband.”

I try to keep my face neutral but, as Edith Sorrel told me quite emphatically that she didn’t have a husband, it isn’t easy.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.