Полная версия

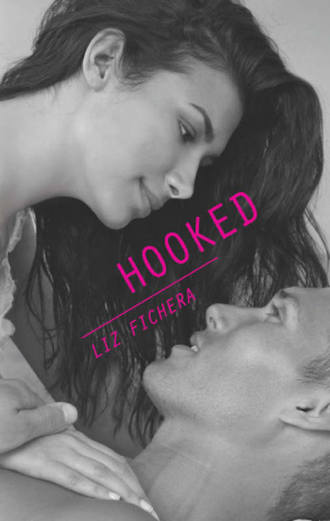

Hooked

Get Hooked on a Girl Named Fred...

HE said: Fred Oday is a girl? Puh-leeze. Why is a girl taking my best friend’s spot on the boys’ varsity golf team?

SHE said: Can I seriously do this? Can I join the boys’ team? Everyone will hate me—especially Ryan Berenger.

HE said: Coach expects me to partner with Fred on the green? That is crazy bad. Fred’s got to go—especially now that I can’t get her out of my head. So not happening.

SHE said: Ryan can be nice, when he’s not being a jerk. Like the time he carried my golf bag. But the girl from the rez and the spoiled rich boy from the suburbs? So not happening.

But there’s no denying that things are happening as the girl with the killer swing takes on the boy with the killer smile....

Ryan

The anger behind Seth’s eyes got worse. The blood vessels around his forehead looked freakishly ready to explode. “Some girl named Fred Oday got my spot.”

“A girl?” I was speechless. My eyes narrowed.

“Here’s the best part,” Seth continued, his voice growing raspier. “Coach isn’t even making her try out.” He chuckled darkly. “He handed my spot right to her.” His glassy eyes stared back at me. “Sweet deal, huh?”

I shook my head. Hardly.

I didn’t even know this girl, but I already hated her.

Fred

I’d been in Ryan Berenger’s classes since freshman year, and he picked today to finally acknowledge my existence.

I’d seen him tons of times at the Ahwatukee Golf Club over the summer, too. He and his short stocky blond friend were always speeding by the driving range in a golf cart. Lucky them, they

didn’t have to wait till after five o’clock for the chance to play for free like I did. Ryan could play whenever he wanted.

And now we were teammates. As my brother would say, that was irony.

That would also explain why he’d glared at me in English class and gripped my book as if he wanted to shred it to pieces. Apparently he’d gotten the news that I was on the team, too. What else would make him so angry?

It’s game-on for Fred and Ryan!

Hooked

Liz Fichera

www.miraink.co.uk

For the memory of my mother and father,

Mildred and Joseph F. Fichera

Contents

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Epilogue

Golf Girl Gab

Acknowledgments

When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced. Live your life so that when you die, the world cries and you rejoice.

—Chief White Elk (Oto Nation)

Chapter 1

Fred

I BELIEVED THAT my ancestors lived among the stars. Whenever I struck a golf ball, sometimes the ball soared so high that I thought they could touch it.

Crazy weird, I know.

But who else could have had a hand in this?

Coach Larry Lannon towered over Dad and me, his shoulders shielding us from the afternoon sun. “So, what’s it gonna be?” he said, his head tilted to one side with hair so blond that clear should be a color. “Are you in?” He paused and then lowered his chin. “Or out?”

I drew in a breath. Even though Coach Lannon had said that I could smack a ball straighter than any of his varsity players at Lone Butte High School, his confidence still rocked me off my feet sometimes. He wanted me on the team. Bad.

“Chances like this don’t happen every day,” he added, and I ached to tell him that they never happened, not to my family. Not in generations.

See, here’s the thing about Coach Lannon. I met him by accident at the end of the summer as I waited for Dad at the Ahwatukee Golf Club driving range. At first I thought he was some kind of golf-course stalker or something. He kept gawking at me as I hit practice balls. It was kind of creepy. I figured he’d never seen an Indian with a golf club.

Anyway, I pretended not to notice and concentrated on my swing. I smacked two buckets of golf balls beside him with my mismatched clubs as if breathing depended on it. After my last ball, Coach Lannon walked straight up into my face and declared that I had the most natural swing he’d ever seen. The compliment shocked me. And when I told him that I was going to be a junior at Lone Butte, one of only a handful from the Gila River Indian Reservation, the man practically leaped into a full-blown Grass Dance.1 He’d been stalking me at the driving range ever since.

Now that school had started, he was making his final pitch to get me to join his team.

“Will you at least come to practice on Monday and give the team a try? Please? If you don’t like it, you’re perfectly free to quit. No questions asked.” Coach Lannon’s lips pressed together as he waited for my answer, although the question was directed mostly at Dad.

From the knot in Dad’s forehead, I could tell he was unconvinced. And the coach didn’t bother hiding his urgency, especially after telling us that he was tired of coaching the worst 5A golf team in Maricopa County. Another losing year and Principal Graser would send him back to teaching high school history full-time, something he didn’t relish. I’d never had a teacher confide something so personal to me like that, not even at the Rez2 school.

Dad pulled his hand over the stubble on his chin, studying Coach Lannon. Deep red-and-black dirt outlined each of his fingernails and filled the crevices across his knuckles, one of the consequences of being the golf club’s groundskeeper. “I don’t know,” Dad said in his lightly accented tones.

Coach Lannon leaned down to hear him.

“Is it expensive?” Dad asked.

“Won’t cost you a thing,” the coach said quickly.

“But how will she get to the tournaments? We only have one car.”

“A bus takes the team. There and back. I can drive her home, if it’s a problem.”

“Are the tournaments local?”

“All except one, but don’t worry about that. I’ll have her back the same day.”

Dad exhaled long enough for Coach Lannon’s eyes to widen with fresh anxiety.

“I’d look after Fred like she was my own daughter,” the coach blurted out. “I’ve got three of my own, so I know how you feel.”

I sucked in another breath as I waited for Dad’s answer. I knew that he wasn’t fond of me traveling off the Rez. The daily trip to the high school was far enough, and not just in miles. He’d agreed to Lone Butte only because our tribe didn’t have a local high school.

After another excruciatingly long pause, Dad said, “I guess when it comes right down to it, the decision isn’t mine. It belongs to her.” He turned to me and placed a steadying hand on my shoulder.

I exhaled.

Dad’s forehead lowered, and he looked at me squarely with eyes that were almond-shaped echoes of mine. “It’s time you made up your mind, Fredricka. Is this what you want?”

I cringed at my old-lady name, but as quickly as it took me to blink, I answered Dad with the lift of my chin. Coach Lannon had said that there’d be a chance I could get a college scholarship if I played well for the team. He said college recruiters from some of the biggest universities attended high school golf tournaments flashing full tuition rides for the best players. No one in my family had ever gone to college. No one even uttered the word. How could I refuse? I only hoped Coach Lannon understood the power of his promises. I wanted college as badly as he wanted me on his team, probably more.

Only a few silent seconds hung between us, but it seemed another eternity. This was the moment I’d been waiting for these past few weeks—my whole life, really. I’d been hoping for something different to happen, something special.

There was only one answer.

“I’ll be there on Monday. I’ll join your team.”

Coach Lannon’s shoulders caved forward, and for a moment I thought he’d collapse into Dad’s arms. He’d probably wondered whether I had the courage to join an all-boys’ team, and why shouldn’t he? It wouldn’t be easy for anybody, least of all a Native American girl from the other side of Pecos Road and the first girl to join the Lone Butte High School golf team.

Before I could change my mind, Coach Lannon extended his beefy hand.

I placed mine in his and watched my fingers disappear.

“We’ll all look forward to seeing you on Monday after school, Fred. Don’t forget your clubs.” Coach Lannon turned to Dad. “Hank?” He extended his hand, along with a relieved grin. “You’ve got quite a daughter. She’s got one heck of a golf swing. She’ll make you proud.” He smiled at me, and my eyes lowered at another compliment.

Dad nodded, but his smile was cautious. He was still uncomfortable with me competing with boys, especially a bunch of white boys, the kind who grew up in big fancy houses with parents who belonged to country clubs. That was why it had taken me two weeks to mention it to him.

But Coach Lannon had explained that there wasn’t enough interest in a girls’ golf team. “Maybe there’ll be a girls’ team next year,” he’d said. “Or the next.” Except by that time I’d be long gone. It was the boys’ team for me or nothing.

And Dad knew me better than anyone. When I’d finally told him, I hadn’t been able to hide my excitement. It would have been easier to hide the moon. Truth be told, it had surprised him. He’d never dreamed that I’d love golf like breathing; he’d never dreamed I’d become so good.

Neither had I.

Fortunately, Dad never had the heart to say no to his only daughter.

“Happy?” he said after the coach disappeared down the cart path, leaving the air a little easier to breathe.

I nodded, my eyes still soaking in the attention. I was beginning to kind of like Coach Lannon. He was okay, for a teacher.

“Good,” he said. “Then I’m happy, too. For you.”

Still dizzy from my decision, I nodded.

Dad sighed at me and smiled. Then he picked up my golf bag, one of his many garage-sale purchases last summer, along with my clubs. The red plaid fabric was torn around the pockets and the rubber bottom was scuffed, but it held all fourteen of my irons and drivers with room to spare. Dad had told me yesterday that he’d try to buy me a new one, but between his job and Mom’s waitressing, there wasn’t a lot of money for extras. And the plaid bag worked just fine.

“Come on, Fred,” Dad said, threading the bag over his shoulder. “Let’s go home and tell your mother. We’re late. She’ll be worried.”

“Uh-huh,” I replied absently as I smashed one last golf ball across the range with my driver. The ball cracked against the club’s face and made the perfect ping. It rose above us like a comet before it sailed high into the clouds.

Thank you, I said silently to the sky, shielding my eyes from the setting sun with my left hand. I waited for the sky to release the ball. One one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand, I chanted to myself like a kid gauging a thunderstorm. The ball hung in the air an extra second before it dropped into the grass and rolled over a ridge.

And that’s when I knew.

My ancestors heard me. I imagined that they asked the wind to whisper, You are most welcome, Daughter of the River People. I was as certain of their loving hands on my destiny as I was of my own name.

* * *

We drove south on the I-10 freeway to the Gila River Indian Reservation in our gray van that was still a deep green in a few spots on the hood. Despite the peeling paint, it ran most of the time. Somehow Dad always found a way to make sure it got us to school and work and then back home.

Home was Pee-Posh, at the foot of the Estrella Mountains where the earth was as dark as my skin. That’s where we lived; that’s where my grandparents had lived and my great-grandparents before them. To reach it, we had to drive for miles along narrow roads with no stoplights, over bumpy desert washes dotted with towering saguaros and tumbleweeds that scattered across the road whenever it got windy. Most days, I wished Dad would keep driving, especially on the days when Mom started drinking.

“Maybe we shouldn’t tell her that I joined the team. Not yet anyway,” I said to Dad without turning. My bare arm folded across the open window as the air tickled my face. I closed my eyes and pretended that the wind was a boy kissing my cheeks. When Dad didn’t answer, I opened my eyes and sighed. “Let’s wait a while. A week, maybe.” Good news only stoked Mom’s bitterness, especially after a few beers.

“You sure?” A frown fell over his voice.

“Positive. Please don’t say anything.”

He smacked his lips, considering this. “If that’s what you want,” he said with a shrug. “Maybe waiting a week is wise. By then we’ll see if you still like being on the team. You could always change your mind—”

“I won’t,” I interrupted him, turning. How could he even suggest it? “Why? You think I’ll fail?”

“Hardly.” Dad turned his head a fraction. “That’s not what I said.”

“You don’t think I’m good enough?”

He chuckled. “Now you’re being foolish. Of course I think you’re good enough. I just don’t want...” His lips pressed together, holding in his words.

“Don’t want what?”

He inhaled. “I don’t want you to get your hopes up and then be disappointed. That’s all. You’ve never played on a team before. And that coach, the boys you’ll play with—well, their ways are different than ours.”

I frowned at him. Of course I know that, I wanted to tell him. But I hated when Dad talked about the old ways. They sounded primitive. And hadn’t I already survived two years of high school?

“Don’t doubt me, Fred. You’ll learn soon enough.”

I turned back to the open window and lowered my chin so that it rested on my arm, considering this. It was true. He had a point. Sort of. I’d never played team sports. I’d never played much of anything; that was part of my problem. “Let’s just not tell Mom, yet. Okay?” I said without turning.

Dad sighed, just as tiredly. “Okay, my daughter. We’ll do as you wish.”

My brow softened with an unspoken apology for being curt, but there was no need. With Dad, forgiveness began the moment the wrong words left my lips. So I smiled at him. But my happiness faded as soon as we drove up the two narrow dirt grooves that led to the front of our double-wide trailer.

Our nearest neighbor lived a half mile away, which is to say that most days it felt like we were the only ones on the planet.

Two black Labs circled the van and started barking as Dad parked under a blue tarp alongside the house. The engine sputtered for a few seconds after the ignition turned off, and then the desert was quiet again except for the doves in the paloverde tree next to the trailer. They cooed like chickens.

Mom sat outside in the front yard on a white plastic chair. Her legs were crossed, and her right leg pumped up and down like it was keeping time. She had a silver beer can in one hand and another crushed next to her chair. “Where’ve you two been?” she yelled. Her words slurred, but there was still enough of a smile in her voice for my shoulders to relax a fraction.

Mom was still in the happy stage of her inebriation. But the happy stage usually morphed into the overly talkative stage, which then blended into the argumentative stage where she brought up a laundry list of regrets, like having gotten pregnant so young or earning a living waiting on stingy rich white people at the Wild Horse Restaurant at the Rez casino. “You’d think a five-star restaurant would attract a better class of people,” she’d complained a thousand times. And that’s exactly when I’d wish that I could disappear into the sky like one of my golf balls. I’d fly high into the clouds and never come back.

“Had to work late,” Dad said. His tone was cautious, like slow fingers checking the wires of a time bomb. “I brought dinner, though.” He raised a box of fried chicken in the air.

“Good.” Mom grinned. “After the day I had, I don’t feel like cooking.” She lifted her hands, spilling some of her beer, revealing splotchy fingers that had spent most of the day juggling hot plates.

Dad bent over to kiss her cheek before turning for the front door, and for a moment the corners of Mom’s eyes softened. “Just need to take a quick shower.” He reached for the torn screen door. It creaked whenever it opened. “I feel like I’m covered in golf course.”

Mom laughed and my throat tightened. Mom used to laugh a lot more. Everybody did.

Then Mom took a long swig from her shiny beer can before resting her narrowed eyes on me. Her head began to bob. “So, Freddy, tell me something that happened today. One happy thing.” She framed it like a challenge, as if answering was statistically impossible. A second beer can crunched underneath her sandal while she waited for my answer.

My mind raced. I sat in the plastic chair across from her and wondered how long it would be before I could retreat to the safety of my bedroom, if you could call it that. My room barely fit a twin bed and nightstand, but at least I didn’t have to sleep on the pull-out sofa in the living room like my older brother, Trevor. “Well,” I said, dragging my tongue across my lips to stall for time. There was no easy way to answer her question. I’d lose no matter what. “I got an A on a social-studies pop quiz today,” I said finally.

“Social studies?” Mom’s wet lips pulled back. She stared at me like I’d grown a third eye. Then she reached inside her blue cooler for another beer. “Who needs social studies? What exactly is that anyway? Social studies?” Her words ran into each other. “How’s that going to help you pay for your own trailer?”

My jaw clenched as I coaxed my breathing to slow. I knew this was only Mom’s warm-up, and I wouldn’t be dragged into it, not today. It wasn’t every day a high school coach begged you to join his team. I only hoped that Mom would drink the rest of her six-pack and pass out like she always did. Then I could practice next to the house where Dad had built me a putting green with carpet samples from the dump.

“I’m not real sure,” I said. “Anyway, it’s not that important.” I certainly wouldn’t share that I’d earned the highest score. That would only make the night more painful, especially for Dad, and I often wondered how much more he could take. He’d left us once, two years ago, and that had been the worst three months of my life.

Mom jabbed her third beer can at me, and a few foamy drops trickled down her fingers. “Don’t lie to me, girl.” Her face tightened into the mother I didn’t recognize. “I can always tell when you’re lying.” Her dark eyes narrowed to tiny slits as she peered at me over her beer can.

“I’m not. Really.” I rose from my chair, my toes pointed toward the trailer, anxious to be inside. “You want me to get you anything?” My voice turned higher. “I’ll heat up the chicken.”

Mom sighed heavily, slurped from her can and let her head drop back. She stared up at a purplish-blue sky where stars had begun to poke out like lost diamonds. The beer can crinkled in her hand. “No,” she said. “Just leave me alone. Everybody, just leave me the hell alone.”

I climbed the two concrete steps to the front door, biting my lower lip to keep from screaming. Even though we were surrounded by endless acres of open desert, sometimes it seemed like I lived in a soap bubble that was always ready to pop.

“Hey, Fred,” Mom said, stopping me.

I gripped the silver handle on the screen door and turned sideways to look at her.

“They’re short a couple of bussers at the restaurant. Wanna work tomorrow night?”

My jaw softened. “Sure. I need the money.” I’d been saving up for a new pair of golf shoes. A little more tip money and I’d have enough. And, thanks to Coach Lannon, I now had a reason to own a real pair.

Mom smiled and nodded her head back like she was trying to keep herself from falling asleep in her chair. “Good girl,” she slurred. “You’ll want to make sure the chef likes you so you’ll have a job there when you graduate.”

I bit the inside of my lip again till it stung. Then I quickly opened the door wider and darted inside. The screen door snapped shut behind me.

* * *

A crescent moon hung in the sky by the time Trevor coasted his motorcycle down our dirt driveway. Low and deep like a coyote’s growl, the engine blended with the desert. I knew it was Trevor because he always shut off the front headlights the closer he got to the trailer. Less chance of waking anyone, even the dogs.

I waited for him on the putting green. With my rusty putter, I sank golf balls into the plastic cups that Dad had wedged into the carpet samples. Dad had even nailed skinny, foot-high red flags into each of the ten cups to make it look authentic. The homemade putting green wasn’t exactly regulation, but it was better than nothing, and he had been so excited to surprise me with it for my birthday last year. The moon, along with the kitchen light over the sink from inside the house, provided just enough of a glow over six of the twelve holes.

“Hey, Freddy,” Trevor said after parking his bike next to the van. The Labs trailed on either side of him, panting excitedly.

“Hey, yourself,” I said after sinking another putt, this time into a hole near the edge that I couldn’t see. I liked the hollow sound the ball made every time it found the edges of the cup. It was strangely comforting. And predictable. The ball swirled against the plastic like it was trapped before resting at the bottom with a satisfied clunk. “How was work?”

“Oh, you know, same shit, different day.” Trevor’s usual reply.

I smirked at his answer. I should be used to it by now, but a small part of me wished that once, just once, he’d surprise me with something different. Something better. Something that could take my breath away.

Trevor worked at a gas station in Casa Grande off the Interstate doing minor car repairs like fixing tires and replacing batteries when he wasn’t making change for the never-ending cigarette and liquor purchases. His long fingers ran through the sides of his thick black hair as he waited for me to pull back my club for the next putt. His hair hung past his shoulders, all knotty and wild from his ride. If he wasn’t my brother, I’d have to say that he looked like one scary Indian.