Полная версия

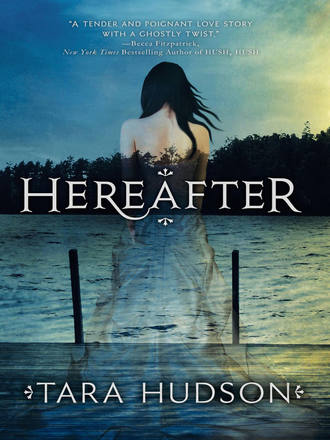

Hereafter

Like my nightmares, the flashes occurred unexpectedly. But instead of terror and pain, the flashes brought something infinitely more appealing: what I could only assume were memories of my life before death.

Nothing significant had appeared yet: a black ribbon fluttering in the wind; the sound of a tire squealing on pavement; the earthy smell of a spring storm. No people, no names, no fleshed-out scenes to give me some clue as to who I was or why I’d died. Nor did I really experience the tastes and smells. The things that occurred in the flashes were more like ghosts of those sensations. But they were enough.

However little I saw, I became more and more certain that these images were mine. My memories from life, breaking free of the fog that death had wrapped around my mind.

And it was because of him. Because of his eyes on mine. Because of his hand upon my cheek, placed there as naturally and easily as it would have been had we been made of the same stuff. Skin, blood, bone. Breathing, seeing, touching.

The mere memory of his skin on mine made me tingle. But not some fleeting, imaginary tingle—this was a sensation. An actual, physical sensation. And the next, most miraculous, change in my new existence.

The first time I’d felt something had occurred on the night of the accident. While I stood on the riverbank watching the lights of the ambulance fade, I’d become aware of an odd, pins-and-needles sensation in the soles of my feet. I stared down at them, confused and afraid. Suddenly, I could feel the mud between my toes and the tickling of the dry grass upon my bare feet. Then, just as abruptly as it had begun, the sensation had ended.

The event had stunned me, to say the least. For so long I’d been desperate for a waking, physical sensation. I’d wanted to feel something, anything. Yet I could place my hand on an object, press myself against it, and it would never matter. I felt nothing. Nothing but a dull pressure that prevented me from going further.

My afterlife had proved all the supernatural stereotypes wrong. I couldn’t walk through walls or float amorphously from room to room. The living people who came close to me didn’t walk through my body but instead seemed to move unthinkingly around me, as though I were just an obstacle in their path.

The only thing I could feel, could affect, was myself. I could touch my hair, my dress, my own skin. After a while this exception provided me no comfort. Actually, it became more of a big, hideous joke: I was trapped in a prison of one. It was as if I existed in my own little dimension, unseen and unheard by others but maddeningly aware of my surroundings.

I have no words to describe the way that made me feel: not only invisible, but also without the power of smell, taste, even touch. Then, how to describe the way I felt when I realized my only physical sensations occurred in the nightmares through which I reexperienced my death?

Or, alternately, how to describe the touch of a hand on my cheek after so long?

Not only was the touch itself extraordinary, but it had also opened some sort of floodgate of sensations.

In the two days following the accident, and at the strangest moments, I would feel things from the living world. Such as the rough bark of the blackjack oak tree against which I’d leaned, or a tiny drop of rain when a brief shower had passed over the river. These feelings came and went quickly, outside of my control.

Yet I found I could control one of them: the little thrill in my veins each time I thought of his skin. This thrill bore a haunting similarity to a quickened pulse in my wrists and neck, so I sought ways to replicate it as often as I could.

I was thinking of his skin again when another flash occurred. Without warning, a scent overwhelmed me, capturing me completely. I froze where I stood, smelling a cluster of late-summer blackberries that clung to a bramble along the tree line. I leaned closer to them, breathing in their smell, tart and overripe under the noonday sun. Although the scent soon vanished and the numbness began to creep back over me, I laughed aloud.

This was the second laugh of my afterlife, and I wanted more of them. Without another thought, I dashed up the steep, grassy embankment to the bridge.

Bounding tall hills in a single breath. Or no breath at all. Super Dead Girl. I laughed again, feeling giddy as I arrived at the top of the hill and began to stride across the grass.

When I crossed the shoulder to the road, however, I froze, one bare foot on the pavement and one on the grass, arms out in an imitation of a trapeze artist.

High Bridge Road.

The words whispered like a threat in my mind, and I immediately had an urgent desire to get away from this place. I could feel a gnawing at the back of my mind, an itch creeping up and down my skin.

Did I sense the stirrings of another nightmare? No, this felt like an entirely different kind of foreboding, one I’d never before experienced.

I shook my head. I was being ridiculous. After all, I was dead. What could be scarier than me?

I forced one foot off the grass and the other farther onto the pavement. My legs moved almost involuntarily, and each step along the shoulder of the road sent unpleasant tingles up my spine.

This is stupid, I thought. I straightened my back. I refused to skulk on the side of the road like a dog with its hair on end.

“Move it,” I commanded myself aloud. I strode forward with purpose, albeit still a little stiffly. Each step unnerved me further, but I didn’t slow until I made it almost halfway across the bridge.

I only stopped when I reached the jagged gap in the waist-high metal railing to my right. Yellow police tape and a few wooden sawhorses stood between the gap and the road, ready and willing to keep absolutely nothing from plummeting off the bridge. The torn railing hung out over the edge of the bridge on both sides of the gap, swaying lightly in the breeze. His—Joshua’s—car had torn a hole at least six feet wide into the railing before flying into the river.

I shivered from the very idea of the crash as well as from the sound of his name in my head. Wrapping my arms around my body, I spared a timid glance at the ground. Streaks of black rubber crisscrossed the pavement where his tires had made a futile attempt to keep him from going over the edge.

It was then I heard the scream, a terrible, pealing sound that shrieked from behind me.

I actually jumped up in the air. An expletive, one I didn’t even know I knew, flew out of my mouth as I turned to face the sound.

Only then did I see that the horrible noise hadn’t been a scream after all. It had been the sound of tires squealing to a sudden stop. Only ten feet away from me, a black car parked, and the door opened.

Without thinking, I relaxed. My ghostly instincts kicked in and told me there was no need to run, no need to fear anything. Because if it drove a car, it couldn’t hurt me. It couldn’t even see me.

But, obviously, my instincts had forgotten the one exception to this rule, even if my heart hadn’t.

A boy climbed out of the driver’s side of the car and slammed the door shut. From his profile I could see he had full lips and a fine nose with just the slightest curve in it, as though it had been broken once but set well. He had almost black hair and large, dark eyes. When he cast those eyes on me, I absently mused that he was a much healthier color than when I’d last seen him.

“You! It’s you!” he cried, pointing right at me.

Without another thought, I turned and ran.

Chapter

FOUR

I was just full of foolish impulses lately. There he stood, the boy about whom I’d been thinking—obsessing, really—for the past two days. Yet I ran, as fast as I could, in the opposite direction. Had any of my adrenaline still existed, it would have burned in my legs as I fled.

Apparently, and as I’d suspected, my ghostly instincts had become as strong as my living ones had been. Ghosts weren’t meant to be seen, no matter how much they wanted to be. Anything to the contrary was cause enough to run away, and fast.

At least those would have been my thoughts were I capable of any. But at that moment I was only capable of blind terror. Fear buzzed in my brain, and it nearly blocked the voice that rang out from behind me.

“Stop! Come on, stop! Please.”

It was the quality of the voice that did it—low, and still a little hoarse from the river water he’d swallowed. Hearing the break in it, I felt a little ache right in the middle of my chest. Just a small, inconspicuous, and completely incapacitating ache.

I skidded to a stop, almost at the other end of the bridge. Ever so slowly, I turned around to face him.

“Thanks,” he called out roughly, settling back on his heels. From his stance he looked as if he’d just been about to take off after me.

I gave him one tense nod. There was a noticeable pause, and then he asked, “So, will you come back here?”

I shook my head. No way.

Even this far apart I could hear him sigh.

“O-kay.” He dragged out the sound of the O as if he was taking the seconds of extra pronunciation to deal calmly with a frustrating puzzle. “Then … can I come over there to you?”

I frowned, not indicating an answer one way or another. I guess he took my indecision as a yes, because he began to walk toward me. He kept his steps intentionally slow, and he held his hands in front of his body in the universal gesture of “I won’t hurt you, wild animal.”

“I come in peace,” he called out, and I could see him grin just a little. The grin was all at once wry, and sweet, and cautious.

So I couldn’t help but grin right back.

The boy dropped his hands and smiled fully at me. And, with that, the little ache exploded in my chest like a bomb, warming every limb.

Warmth. I felt warmth. Really felt it, just like I’d felt the touch of his hand in the water. My smile widened.

“Does that smile mean I can keep walking toward you?”

“No,” I said quietly.

He stopped moving, surprised by my words, or maybe just by the sound of my voice. “Really?” he asked after a moment.

“Walk over to the grass,” I instructed.

He frowned, knitting his dark eyebrows together. “Why?”

“I don’t like this road. I want to go back over there.” I jerked my head in the direction of the embankment I’d only recently left.

He kept frowning, but that grin twitched at the corners of his mouth again.

“O-kay.” He gave me a thoughtful look, holding my gaze. The message was clear: I was the frustrating puzzle with which he was calmly dealing.

Then he smiled, closed lipped and dimpled like a little boy, and gave me a quick nod. He shoved his hands in the pockets of his jeans, turned on one heel, and began strolling back to the embankment.

Slowly. Too slowly. Swinging his legs in an exaggerated, deliberate way. I sighed loudly.

“Could you hurry up, please?”

He laughed, still walking away from me.

“You have a way with giving orders, you know that? Not a master of the casual chat, are you?”

Given that you’re the first person I’ve talked to in God knows how long since my death …

Aloud I muttered, “You have no idea.”

I could tell he’d heard me because he hesitated just a little. Then he kept walking forward, minus the mocking swing of his legs. After he’d gone about ten feet, I began to follow him. I walked even slower than he did, trying to think, think, think of what I was going to do, or say, when he stopped.

Blessedly, he kept going, past the black car and past the end of the bridge. Then onto the grass of the embankment. I was worrying so deeply about our upcoming exchange, I didn’t notice when he stopped and turned toward me. I looked up in time to jerk to a stop just a foot from him, within touching distance.

Terror raced through me. I could have run into him. If that had happened, I would have either felt him, skin against glorious skin, or I would have felt nothing but the numbing, impossible barrier. Either way, he surely would have realized something was wrong and do exactly what he should: get away from me.

“So,” he began, casually enough.

“So,” I responded, my eyes going to my bare feet. I felt ashamed, terrified, excited.

“I’m Joshua.”

“I know.”

“I thought so.”

The humor in his voice made me look up, finally meeting his eyes. As I suspected, his eyes were very dark, but not brown. They were a strange, deep blue—an almost midnight sky color. I was certain I’d never seen eyes that color before, and they had a disconcerting effect on me. I felt even more flustered just staring into them.

I was suddenly, uncomfortably aware of my own appearance: the tangles in my hair; my deathly pale skin; my hopelessly inappropriate dress with its strapless neckline, tight bodice, and filmy skirt. I probably looked as if I was headed to some sort of dead girls’ beauty pageant. For the first time in a very long time, I wished I had access to a mirror, whatever good it would do someone who couldn’t cast a reflection or change clothes.

He didn’t seem to notice my discomfort, however. Instead, he looked right into my eyes and grinned at me, although his expression had lost some of its amusement. He looked more speculative now, as if he knew there were mysteries between us. Questions.

“So,” he started again.

“You already said that.”

“Yeah, I did.” He laughed lightly and looked down at his shoes, absentmindedly running one hand through his hair and then leaving it on the back of his neck.

There went my little ache again, flowing out of my core like a pulse. That absentminded gesture—the guileless sweep of a hand through his hair—was utterly endearing. He looked so vibrant, so alive, that the words spilled right out of me.

“You want to know what happened, don’t you?”

I recoiled from my own words, blinking like an idiot. Stupid, stupid, stupid.

“Yeah, I do. I really do.” He dropped the hand from his neck and stared at me more intently, the playfulness entirely gone from his eyes.

Crap.

“Well, that’s a matter of opinion, Josh,” I said aloud.

“Joshua. Joshua Mayhew,” he corrected instantly. “But my name’s not really important right now.”

Deflect. I had to deflect, and fast, so I blurted out the first question that came to mind.

“Why am I supposed to call you Joshua if everyone else calls you Josh?”

“You’re not everyone,” he said bluntly. “Anyway …”

He knew I was stalling and meant to lead me back to the original trail of conversation, that much was clear. What was less clear was whether or not he meant any flattery by his words.

“Um …,” I floundered, and did something I hadn’t done since my death: I fidgeted. I grabbed at my skirt and began to twist it. I had no idea where to go from here.

Neither did he, it seemed. He watched me worry at my skirt and then he stared at my face until I eventually met his gaze.

“What’s your name?” His question was soft, gentle. He wasn’t trying to lead me back to the conversation. He really wanted to know.

“Amelia.”

“What’s your last name, Amelia?” His voice wrapped so well around my name, I flustered out yet another stupid answer.

“I don’t know my last name.” Or, at least, I’d never felt brave enough to try and find it in the graveyard.

He blinked, taken aback.

“Huh. Where do you live?”

“I don’t know that, either.”

Disarmed. I was completely disarmed. That was the only reasonable explanation for my stupidity.

“O-kay.” The long O again. He wasn’t as playful with the sound this time.

He stared down at his canvas sneakers, frowning and digging the toe of one shoe into the grass. He shoved his hands back into his pockets and rolled his shoulders forward, a reflexive gesture that made him look boyish and sweet. After a few more silent moments, he looked back up at me.

“You know, we have a lot to talk about.” His eyes, serious and urgent, met mine. My little ache curled out even farther in my chest as he continued. “I would have come and found you sooner, but they wouldn’t let me out of the hospital. Apparently my heart may have … Well, I may have … died, a little. In the water.”

He tilted his head to one side, clearly gauging my reaction. I shivered, but I didn’t look away. I probably didn’t look too surprised by his choice of words, either. After all, I was there when it happened. My face obviously answered some unasked question of his, because he nodded again.

“So,” he went on, “after I got out of the hospital, I started asking around about you. But nobody saw you that night. Not my family, not my friends, not even the paramedics. Not only did nobody see you on the shore, but nobody saw you in the water with me. Which I find weird. Because you were in the water with me, weren’t you?”

I bit my lower lip and nodded slightly.

“I knew I didn’t imagine you. Well, maybe when I was, you know, dead.” He said the word as if he was afraid of it. “But not after. Not when I swam to the surface or when I made it out of the water.”

Still biting my lip, I shook my head. No. You didn’t imagine me. You saw me.

“I practically had to steal my dad’s car to get out of the house today, and I came right here—to the scene of the crime. And here you are.”

“Yes,” I whispered, totally lost for a clever response. “Here I am.”

“So,” he whispered back, “we have a lot to talk about.”

“You already said that.”

He laughed, and the sound surprised us both. Then he nodded decisively.

“Well, here’s how I see it, Amelia. We don’t have to talk now. I have to get the car back to my dad soon anyway, since I’ve spent the whole morning stalking you. Besides, this doesn’t seem like a conversation you want to have, especially in this place. Can’t say that I blame you.” He glanced quickly at the hole in the railing, shuddered, and then looked back into my eyes. “So, tomorrow I’m going to be at Robber’s Cave Park. Do you know where that is?”

Stunningly, impossibly, I nodded yes.

I knew the park. I suddenly knew it as well as I knew my first name, and I knew the direction of the park from where I stood now. I knew it from memory, a genuine one that hadn’t flashed into and out of my mind but just … was.

What was this boy doing to me?

“Okay, good. I’m going to sit at the emptiest park bench I can find. I’m going to be there at noon, because, unfortunately, I’m healthy enough to go back to school tomorrow. I think I can talk my parents into letting me skip fifth period—play the sympathy card with them—but noon’s the earliest I can get there. So I’m going to go to the park. And I’m going to wait for you.”

“And if I don’t show?”

He shrugged. “I’ll respect your privacy. Or I’ll pursue you all over the earth like I’ve been trying to do since they let me out of the hospital. Probably the latter.”

I should have been afraid. I should have run away again, hid until the years passed and Joshua became an old man and the fog wrapped around my dead brain again.

Instead, I smiled.

He gave me a slight nod, grinned, and walked past me back to his car.

“Till tomorrow,” he called out with one small, backward glance.

I watched him walk away, once more unsure of everything. But when he opened his car door, my incapacitating ache curled again. My impulses, it seemed, were still doing unfamiliar things to me, because the ache seemed to have incapacitated everything but my big mouth.

“Joshua?” I called out, a slight hitch in my voice.

“Yeah?” He spun around immediately. I could swear he looked expectant, maybe even eager.

“What do I look like to you?”

He tilted his head to the side, frowning.

“What do I look like to you?” I repeated urgently, afraid that if I didn’t talk fast enough, I would have time to realize how absolutely, mind-bogglingly stupid I sounded.

Joshua smiled. He answered me, so quietly I almost couldn’t hear him.

“Beautiful. Too beautiful for people not to have noticed you the other night.”

“Oh.” The little sound was all I could manage.

He stood up straight then and cleared his throat. “So … um … I’m going to leave before I say anything else that makes me sound like an idiot. Tomorrow?”

I nodded, stunned. “Tomorrow.”

Joshua, too, nodded. Then he got into his car and reversed it back off the bridge, giving wide berth to the gap in the railing. With one quick, final spin, the car pulled away, disappearing from sight around a curve.

Chapter

FIVE

Hours can pass like years when you wait impatiently for something, especially something you crave and dread in equal measure.

What I craved, in a manner so intensely I nearly ached from it, was to see Joshua’s face and to hear his voice. Wandering and dreaming of him, I’d never imagined Joshua would be able to see me and talk to me again, much less that he would want to. I hadn’t anticipated how much I would want it too. How much my longing to be seen, and specifically by him, would intensify each time I was.

But seeing him again meant telling him the truth.

Sitting on the riverbank after Joshua left, I felt certain I wouldn’t be able to lie to him the next day. Not if my completely ridiculous behavior on the bridge proved any indication of my ability to deceive him. If I saw him in the park, and we spoke, I would undoubtedly tell him everything: what I’d seen under the water, and what I really was. Which, in turn, would undoubtedly drive him away from me.

So even if I went to the park, I probably wouldn’t see him again afterward. Presuming this, I had to ask myself what would hurt worse: the numb loneliness of invisibility or the aching loneliness of an outright rejection from the living world? I knew the awful boundaries and depths of the former, but I had no idea how excruciating the latter could, and likely would, be.

Following this line of reasoning, I came to a decision about my course of action the next day. I wouldn’t go. I would hide. I would protect my dead heart from anything worse than numbness.

And I would probably feel miserable about it for years. I lay my arms across my knees in a posture of defeat.

That’s when something made my head jerk upward and then made me jump up into a crouch on the grass. At first I couldn’t be sure what made me react this way. When I tried to glean some clue from my surroundings, I noticed that the sun had nearly set while I sat feeling sorry for myself. It threw a fiery glow across the water and cast deep shadows into the woods.

Yet it wasn’t the dying sunlight that had frightened me. It was instead the thing that contrasted so sharply with the burning light of the sunset: a bitterly cold wind that now lashed across my bare legs and through my hair.

I’d been experiencing so many unexpected sensations lately that perhaps I shouldn’t have been so alarmed by the wind. But I was.