Полная версия

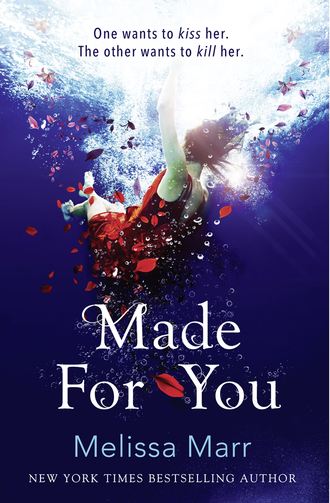

Made For You

“I don’t think I … I don’t remember anything,” I tell her. My voice wavers a little, but I’m not as upset as I probably should be. I feel sort of like I’m in a haze, which raises another question. “What am I on?”

“An antiseizure drug, a muscle relaxer, and … I’m not sure what else.” Grace glances at the bag of medicine. “Sugar water or something for hydration. Plus sedatives and stuff from the surgery.”

“Where’s your mom?” I ask. I’d heard Mrs. Yeung earlier, but I don’t see her.

When my parents travel, she’s my unofficial mom. Truthfully, she fills that function even when they’re home, but when they’re away, she has a signed power of attorney form for emergencies. My parents trust her completely—and for good reason. Mrs. Yeung has all the traits that “good Christians” in the South are supposed to have, including a few that my parents lack. She’s a stay-at-home mom who gave up a career to move to our little backwater town in North Carolina with her husband when he got a chance at his dream job.

“She had to leave,” Grace says. “We’ve been here a lot, and Jimmy had to miss a game already. She wanted to stay till you woke, but—”

“She was here when I needed her,” I interrupt. “She’s awesome.”

Grace scoffs. “Yeah, you say that because you don’t live with her. The other day …”

I know that Grace is still talking, but I can’t focus on what she’s saying. Things don’t add up. I remember leaving the coffee shop. Robert was to meet me, but he didn’t show. We didn’t argue at the party the night before. He was distant, but we didn’t fight or anything. We never really fight. We’re friends who’ve known each other since the cradle and decided to date last year, but honestly, we still mostly feel like friends who sometimes have sex. Fighting isn’t an issue for us, so when he didn’t show for our date and didn’t answer when I called—or when I texted him—I was confused.

Both my parents and Grandfather Cooper were out of town. Grandfather Tilling was home, but he goes to bed early, so I didn’t want to bother him, and I felt stupid calling Grace to come pick me up when it was only a couple miles to walk. Really, it would’ve taken longer for Grace to get there than it would for me to walk it.

“I was on my way home. I remember that. Robert forgot me or something.” I look at Grace, as if her face holds the secrets I can’t find inside my memories. Sometimes with Grace it kind of does. She’s very readable. She squeezes my fingers, and I notice that I’m still holding on to Grace’s hand.

“You got hit by a car when you were walking, sweetie.”

“Hit? Like someone ran over me?” I try to remember, but I have nothing. It’s a bright blur there when I try to think about it.

“Yes.” She starts to tear up and adds quickly, “But you’ll be okay. You hit your head; they call it a traumatic brain injury. That’s why you can’t remember things, and you have a broken leg, some bruised ribs, and … lots of black and blue.”

But Grace looks down and won’t meet my eyes, and I know there’s more.

My mouth feels like the desert looks, and I have to swallow before I can prompt, “And? Am I …” I look down at my feet and quickly wiggle my toes. Then I glance at my stomach and arms. There’s a bandage on my right forearm, as well as scrapes and cuts on my hands. The cuts aren’t as bad on my left arm, but my right biceps is liberally decorated with slashes and dots. My left arm is scratched and cut, but nothing severe. Looking at my skin isn’t going to tell me if there’s something really wrong under it though. “Did I lose an organ or …”

“No! You still have all your organs; you’re not paralyzed. You’ll be fine,” Grace hurriedly assures me. “They put a plate in your leg, but that’s not going to mean much other than physical therapy. You hit your head pretty hard, and we were scared about that. You were out for a while, but you’re awake now and seem okay so … that’s good, too.”

She’s still avoiding saying something though. I know her too well for her to succeed at it. For someone so eager to dive into confrontation with most people, she treats me like I’m in need of sheltering. I take a deep breath and ask, “And? Just tell me.”

“There was a lot of glass. That’s all. You got some cuts, like on your arm. The big injuries were your leg and your head … your brain, really, but it seems like they’ll be fine.” She holds my gaze as if staring at me will keep me from reading whatever secrets she wants to hide. I know she’ll tell me; she always tells me even when she doesn’t want to do so. Earlier this year, when Amy blabbed to everyone at school that I had slept with Robert, Grace tried to protect me. She shielded me from the things people were saying, but even then, she gave in after a couple of days and spilled. I don’t want to wait this time.

“Gracie … what aren’t you saying?”

She sighs and hedges, “You’re going to have some scars on your face. It’s not really that b—”

“Mirror.”

“Sweetie, maybe not yet.”

“Mirror,” I repeat, louder this time.

“Eva, let’s just wait until you’re feeling better, and it’s heal—”

“Please.”

I watch Grace dig through her bag and pull out the little silver compact that her grandmother gave her for her sixteenth birthday. For a moment, Grace holds it in her hand, squeezing it so tightly that her knuckles look like the skin has grown thinner there.

She holds it out to me, and I don’t let myself hesitate. I’m not vain, not really. I’m not the most beautiful girl in the world, but I’ve always been pretty enough to not be jealous or insecure. I have dark blue eyes, a smallish nose, lips that look pouty, and cheekbones that are defined without looking razor-sharp. I’m not opposed to wearing makeup, but I’ve always been happy that I don’t need it.

I gaze at the reflection in the glass. The girl I see now needs makeup badly. Red lines crisscross my face. Dark blue stitches highlight some of them. As much as I want to, I can’t look away from the tiny reflection of myself, and I’m glad that Grace’s mirror is so small.

I reach up to touch the black-and-blue marks and cuts on my throat, but before I can, Grace grabs my hand. “No touching. The nurses said you shouldn’t irritate the wounds. We had to keep your wrists restrained at first.”

Even as she tells me that I was tied to my bed, which is disturbing on some basic level, I can’t look away from my reflection. I dart my tongue out to touch the cut on my lip and promptly wince. I don’t hurt like I should, and I know that it’s because of the medicine coursing through my body. One particularly long cut runs from just under my eye to the side of my cheek where it curls under my ear and vanishes into my hair. That one has been stitched. Vaguely it registers that the ones deep enough to need stitches are the ones that’ll scar the most. Some of the others are only shallow cuts like the ones on my arm, so I think they’ll fade.

The tiny cuts vanish under the top of my shirt, and I look at my arms again. I was wearing a long-sleeved shirt when I walked home. Maybe that protected them a little, or maybe it was just how I hit the ground or how the car hit me. All I know for sure is that it’s my face that took the worst of the impact. I glance back at the mirror, hoping for a moment that it isn’t as bad as I first thought. It is though. No amount of healing is going to make these all vanish.

I close my eyes, and Grace takes the mirror from my hand. She doesn’t tell me that everything is okay or that it’s not as bad as it looks. She might try to hide things from me when she thinks it’s for my own good, but she doesn’t ever lie to me.

The day of the accident was the last day I was pretty.

DAY 5: “THE VISIT”

Judge

WHEN THE CAR HIT Eva, the thump of her body was louder than I expected. It reminded me more of hitting a deer than a possum. I’m not sure why I was surprised. Girls aren’t the same size as possums, but I suspect I thought more of her nature than her size. The initial thump of her body was followed by a thud as she fell against the car hood. I’ve dreamed about it twice since I hit her, since I thought I’d killed her.

I swallow and keep walking toward the entrance. No one looks at me any more than they do the nurses and techs that fill the halls at Mercy Hospital. I’m part of the scenery here. I’m nobody important.

Neither is she.

I can’t tell anyone that though. They wouldn’t understand. It’s not that I need approval. I don’t. I don’t need a lot of things. What I do need is to see Eva. I’ve been thinking about it—thinking about her—since she fell. I have to know if she’s really alive.

The article in the Jessup Observer says she is. I carefully clipped it out to save for my book, but after the fourth read, I needed a second copy because the ink was smeared and the edges were crumpled. I was careful with the second copy. Now, though, I hold the original clipping in my hands.

Eva Tilling, the granddaughter of both Davis Cooper IV (Cooper Winery owner and CEO) and of the esteemed Reverend Tilling, suffered multiple serious injuries after a hit-and-run earlier this week.

Miss Tilling, 17, underwent surgery this week and remains at Mercy Hospital in Durham, where she was transported after the incident. She is in critical but stable condition.

The victim was walking unaccompanied when she was run down by an as yet unknown vehicle. Authorities believe Tilling was only alone for moments after being struck when another passing vehicle saw her unconscious along the road and called 911.

The Jessup sheriff’s office is looking for witnesses to the incident. They said evidence has been recovered but declined to discuss specifics.

An arrest has not been made at this time.

The staff at the Jessup Observer would like to extend our prayers and thoughts to both the Tilling and Cooper families during this difficult time.

I know the staff writer has to suck up to the Cooper-Tilling family. No matter what They do, they’re always thought innocent. The paper is only one of the many things They control. I didn’t realize it a few years ago, but I see it now: Jessup is owned by Them, the ones who support the crazy rules that govern every interaction in Jessup. I’m not ruled by Them, not now, not ever again. Eva wasn’t either, but that changed. She became corrupt. I have seen it, dirt on her flesh where the corruption has begun to take root. She was the shining light, the proof that not everyone believed Their lies. Then she fell. She became just as guilty as the rest of Them, so I had to act before the corruption consumed her. It’s like a disease, eating away at all that’s good and pure.

I ran over her to save her.

I was willing to let her die in order to save her. I’m like Abraham with Isaac, willing to sacrifice the one I love above all others. Like Abraham, I lowered the knife—or car, in my case—but God spared my beloved one. Now, I am waiting, hoping, praying for a reward for my faithfulness.

I’m praying that her acceptance will be my reward.

As I approach the metal detector at the hospital, I wrap my arm around the large arrangement of flowers as I fish out my wallet with my other hand. I don’t have an ID in it, but I brought an empty one so as not to draw attention. I drop it and my clipboard into the bin, and then I step through the arch with the flowers. The guard barely looks at me.

I look a little older than I am, and with the scruffy facial hair and hat, the guard probably assumes I’m in my early twenties. He sees the flowers and uniform, and he fills in the rest of the facts to match the image. It’s enough for him to shift his attention to the next person. I gather my items and keep moving.

The flowers aren’t ostentatious, but they’re still large enough to be believable as a gift from the paper. My clothes are nondescript enough—black trousers, navy button-up, and a navy-and-white ball cap. My shoes are plain black, too. Nothing here stands out. Still, I tug the ball cap down a bit farther to shade my face and hold the floral arrangement up and to the side. I stopped in earlier to get a look around the lobby. A camera aims at the door, and another sits in the back far corner of the ceiling behind the reception desk.

A bored woman glances up as I approach the desk.

“Pediatrics,” I say.

“Fourth floor.” She motions toward the elevators.

A second security guard stands nearby, but he’s not here to stop deliveries. Being the intersection of the east–west I-40 and north–south I-85, Durham has long been a high drug-trafficking area. It’s not as bad as it once was, but the hospitals have security due to drug-related crimes.

Inside the elevator, I look at the flowers. We talked about the language of flowers in one of our lit classes because of Hamlet, so I know that Eva will figure it out. The flowers I picked are yellow roses (for apology and a broken heart), white roses (for silence and purity), red carnations (for passion), and white daisies (for innocence). The daisies were in Hamlet too, so I know she’ll see them as a clue. She’ll figure it out.

I’ve already removed the Harris Teeter grocery price tag, but I check again to be sure there are no other identifying marks that will ruin my disguise. I keep my eyes downcast in case there’s a camera in here, too. By the time I reach the fourth floor, where Eva is, my hands are trembling a little, not noticeably enough that strangers would see, but I feel it. Intentionally, I step on the long piece of my shoelace as I walk, untying it as I approach the desk. I tied and retied it repeatedly to get the length right. I’d practiced as I walked around at home, too. Today, I’m doing everything right. Today, I’m not going to get impatient. It’s hard though. I didn’t think I’d ever see her again—aside from her funeral. I knew what I’d say there. I’d planned it. The words, the pauses, I practiced. I may change it some now that I have more time.

Maybe I won’t have to say the words at all.

When I saw the article, when I found out she was alive, I knew it was a sign. God doesn’t want her to die yet. I understand that now. I was hasty. I have spent the past three days thinking about the right path, praying for clarity and considering my options. He’s giving me another chance, giving her another chance. Maybe I can make her see, and she can be redeemed. If I save her, she can live, and she’ll be so grateful for all that I’ve done to save her.

I stop at the desk and tell the receptionist, “Delivery for”—I glance at the clipboard as if I don’t know her name, as if I could ever forget her name, and read it—“Eva Tilling.”

“That girl gets more flowers than the rest of the floor combined!” the woman says as she signs on the clipboard where I silently indicate. The sheet is very convincing. I ordered my own flowers so I could have a good model for my form.

Once she walks away, I glance at my shoe as if I am just now seeing that it’s untied. No one seems to be watching, but you never know. I crouch, my posture allowing me to use my hat to hide my face as I watch her carry the flowers to a room. She taps on a door, and I finish tying the shoe as I watch her go inside.

Straightening, I glance around. No one pays much mind to delivery people. So many flowers arrive at the hospital. Why would they look at us?

I force myself not to hurry. We wouldn’t be in this situation if I had practiced patience in the first place. Hurrying is dangerous. Slow and steady wins the race, especially in the South. My grandmother told me that so often that I’m sure she’d take a switch to me if she knew that I’d messed everything up by being impatient.

I glance inside Eva’s room as I pass it. It’s only a moment, a split second, but she’s there. She’s awake and speaking softly. If I didn’t know better, I’d swear she was an angel. She’s not though. She’s one of Them. If I can’t save her, she’ll have to die. She’s been spared for now, but I need her to understand. If she doesn’t, she’ll be a sacrifice at the altar of venality.

Like the rest of Them should be.

My mouth is dry at the thought of how close I am to her now. I could walk straight into her room and visit her, but I’m not ready to talk to her. Still, I needed to see her.

I wonder if she’ll notice my name on the card. I listed several names—the editor, a few staff writers, and then I added my own in the middle. Judge. It’s not the name I was born with but it’s my true name, my soul name. I’m not really an executioner yet, and without Eva, I’m not a jury. Together, we could be a judge, jury, and executioner.

I’d despaired when I realized that she was one of Them. On the night I tried to kill her, I thought I would be always solitary. Now that she survived, I have hope again.

Outside, I pause to breathe the already thick air. Early summer in North Carolina isn’t as humid as the heat of July and August, but the air is heavy already. The sweet taste of wisteria fills my mouth, and I wonder if Eva likes the flowers. They’re not as sweet as the pale purple clusters of wisteria clinging to the trees. For her, I brought common flowers—like her, not truly special. That was my mistake before: I raised her up like a false idol. I know better now.

I cross the parking lot to the car I have today and slip on my gloves before I touch the handle. Like my uniform, it’s not memorable, a dark blue, four-door sedan. I’ll park it beside the one that has Eva’s blood on it.

DAY 5: “THE DETECTIVE”

Eva

I’M ALONE. SO FAR, my friends are respecting my “no visitors” stance, and my parents are still stuck in Europe. Apparently, there was another volcanic eruption in Iceland that pretty much shut down all the flights in and out of Europe. It was nothing but smoke, ash, and gas, but Dad explained that when that same thing happened back in 2010, flights were cancelled or disrupted for over a week. I’m not counting on them getting here anytime soon. I don’t need them to rush home anyhow. I’ve told them that several times. I told Grandfather Cooper the same thing when he called from somewhere in Alaska on one of his cruise-tour things.

Grandfather Tilling came by the hospital to sit with me, and of course, he had his congregation pray for me. It didn’t occur to me to ask him or Mrs. Yeung to be here for the police visit I’m about to have.

Right now, I wish it had.

“Are you sure you’re ready to talk to the detective, Eva?” my nurse asks again.

“Yeah.” I offer the nurse a smile, but I’m not sure if it’s encouraging with the way my cuts and bruises must still look.

“If it gets too much, you can stop the interview,” the nurse says kindly.

My nurse helps me to sit up, and maybe’s it’s silly, but I have her get my brush so I can combat some of the snarls. I don’t use a mirror because I can’t stand seeing my own reflection. I’m not sure I ever want to see my face again. I certainly don’t want my friends to see it. I’d like to cling to the image in my memory, not replace it with this one. Without a mirror, I can’t put on even the little bit of makeup I might be allowed, so there’s nothing to be done for my face.

When the police officer comes into the room, she looks at me the same way she looks at everything else: like she’s taking mental notes. I realize that she’s the first person other than Grace, Mrs. Yeung, and the hospital staff to see my face. I’m glad the detective isn’t gawking at me.

“Hi,” I say because I’m not sure what else to say. I’ve never been interviewed by a police officer before. I’d rather deal with the doctors than talk to the police.

“I’m Detective Grant,” she says. Her hair is pulled tightly back in a knot, but it only makes her features more noticeable. She wears no makeup, but her skin is enviably perfect. I realize that I wouldn’t have envied it before the accident, but now I’m looking at her and can’t help thinking that no one will ever again look at me the way I’m studying her right now.

She holds out a business card as she introduces herself, and then drops it on the stand beside my bed between my lip balm and iPhone. “I’m going to record our talk so I don’t miss anything,” she starts. Once I nod, she turns on the recorder and continues, “Why don’t you tell me what happened?”

“I don’t remember much,” I admit, feeling embarrassed at not knowing the details of what is probably the most significant thing that’s ever happened to me.

She sits in the chair beside my bed. “Tell me what you do remember.”

“I was walking home right after sunset, so it was still sort of light out.” I feel idiotic as I try to explain what little I know. “My boyfriend wasn’t answering, and I didn’t want to bother my friends, and my parents were away, and really, I’ve walked home plenty of times.”

“Did you see the vehicle?”

I think about it again. Dr. Klosky says it’s normal for there to be memory issues with head trauma, but that doesn’t do much to make me feel okay with it.

“I don’t know,” I admit.

She nods. “Were you walking on the side of the road? Were you wearing something visible?”

I try again to think back to that day, but the details aren’t there. “I always walk on the shoulder,” I say, sounding slightly desperate even to myself. “I don’t remember, but I can’t think of any reason I wouldn’t do the same things I always do … Did they find me on the side of the road?”

“Yes. The driver who found you didn’t see a car at the scene, but you were visible from the road.”

I swallow. I was visible. It was dusk. Someone hit me and left me. As the facts and her tone register, it finally occurs to me that this might not have been an accident. The monitor that keeps track of my heart rate and blood pressure beeps. We both glance at it. I’m not sure what the numbers are supposed to be, but I know they’re increasing.

My nurse today, whose name I can’t remember, pops into the room and glares at Detective Grant. She does something with the monitor, and the beeping stops. “Do you need to rest, Eva?”

I suspect Detective Grant and I both hear the real question: does this police officer need to go away? It’s not the detective’s fault I’m upset, so I shake my head. “I’m okay.”

“Do you want me to stay?” she offers.

“No. I’m okay.” It’s funny how we lie to be polite even when the evidence is present to contradict us. The monitor’s recent beeping makes it very apparent that I’m not fine.

“I’ll be back to check on you shortly,” the nurse says, sounding a lot like she’s warning us.

Once she’s gone, I look back at Detective Grant. “I get where you’re going, but no one would want to hurt me. I’m not bullied or a bully. It just doesn’t make sense. This had to be an accident.”

“What about your social life? Has anything happened recently to cause waves? Any rivalries?”

I shake my head. “I don’t do sports or clubs or anything. My boyfriend’s on the basketball team, and my best friend does track. No enemies or dramas related to either of them … or anyone else really. My life is pretty routine.”

“What about your family? Are you aware of your parents having any unusual upheavals or strange events? Threats? Anything at all that’s stood out to you.” She has one of the least readable faces I’ve seen, and her tone is level.

The questions still unnerve me, and the monitor starts beeping again. I don’t need to look at it to know that my pulse is speeding. “Do you have a reason to think it wasn’t an accident?” I ask.

My nurse comes back in. She folds her arms over her chest and levels a stern gaze at Detective Grant, who stands but doesn’t answer me.