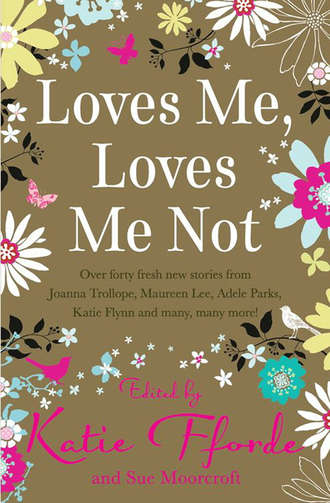

Loves Me, Loves Me Not

Полная версия

Loves Me, Loves Me Not

Жанр: исторические любовные романызарубежные любовные романыисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литературасерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу