Полная версия

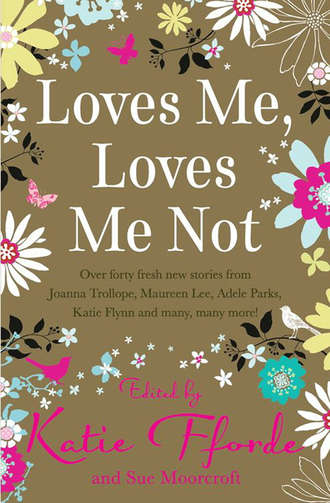

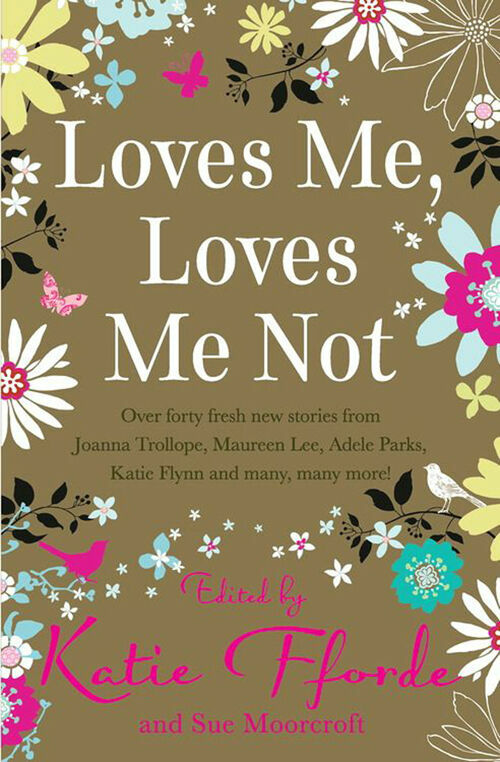

Loves Me, Loves Me Not

Loves Me,

Loves

Me Not

Edited by

Katie Fforde and Sue Moorcroft

Loves Me,

Loves Me Not

Joanna Trollope

Nicola Cornick

Judy Astley

Benita Brown

Jane Gordon-Cumming

Sue Moorcroft

Victoria Connelly

Amanda Grange

Jean Buchanan

Anna Jacobs

Nell Dixon

Liz Fielding

Anita Burgh

Joanna Maitland

Adele Parks

Rita Bradshaw

Elizabeth Bailey

Annie Murray

Jane Wenham-Jones

Rosie Harris

Trisha Ashley

Carole Matthews

Louise Allen

Sue Gedge

Rosemary Laurey

Charlotte Betts

Elizabeth Chadwick

Katie Fforde

Sophie King

Jan Jones

Janet Gover

Maureen Lee

Linda Mitchelmore

Christina Jones

Geoffrey Harfield

Margaret Kaine

Theresa Howes

Gill Sanderson

Debby Holt

Sophie Weston

Katie Flynn

Margaret James

Eileen Ramsay

Diane Pearson

www.mirabooks.co.uk

To the wonderful, talented members of the

Romantic Novelists’ Association

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Romantic Novelists’ Association would like to thank all of its members who contributed to this fabulous anthology. And also, Caroline Sheldon, for her help and support.

FOREWORD by Katie Fforde

I have been a member of the Romantic Novelists’ Association since before the dawn of time or before I can remember, anyway. It’s hard to say if I would have become a published novelist without them but I suspect not. Like reading romantic fiction, which has always been what got me through the tough times and still does, the RNA is a constant support. Without them I might well have given up, without them I would never have known the many writers who are now my friends. The joy of my first meeting when I realised I was not the only mad woman in the attic, typing away when I should have been ironing, cooking or generally being a wife and mother, was immense.

Thus, it is a complete pleasure to be asked to be involved with this fabulous anthology. It really is a box-of-chocolates of a book. There is everything in here, whatever your taste. There’s sophisticated chic lit, tender romance—funny stories, scary stories and even fairy stories—and every other sort of story you can think of, including a vampire story.

One of the things I particularly like is it represents the vast range of writers and writing that the RNA embraces and shows the sparkling talent that our organisation represents.

Romantic fiction is a very popular, and demonstrably broad, genre and in here you don’t just get a lot of wonderfully good reads, you get real value for money.

Enjoy—you can dive into this without putting on an ounce!

Joanna Trollope

Joanna Trollope has been writing for over thirty years. Her enormously successful contemporary works of fiction, several of which have been televised, include The Choir, A Village Affair, A Passionate Man and The Rector’s Wife, which was her first number one bestseller and made her into a household name. Since then she has written The Men and the Girls, A Spanish Lover, The Best of Friends, Next of Kin, Other People’s Children, Marrying the Mistress, Girl from the South, Brother and Sister and Second Honeymoon. Her latest novel is Friday Nights. Joanna also wrote Britannia’s Daughters—a non-fiction study of women in the British Empire, as well as a number of historical novels now published under Caroline Harvey. Joanna was awarded the OBE in 1996 for services to literature.

Find out more at www.joannatrollope.com

Rembrandt at Twenty-Two

I promise you, I saw him from the stage. I couldn’t miss him, not the way he was looking at me. I was up there, front row, final chorus, stockings and suspenders, and he was out there, in the stalls, centre, only two rows back. Our eyes met. Well, not just met. Our gazes kind of fused. I’d never known anything like it, and there isn’t a name for it, that kind of attraction, and perhaps there shouldn’t be, because it’s different every time, different for everyone.

Well, of course, he was waiting at the stage door.

He said, ‘Hello, gorgeous.’

I said, ‘You foreign?’

He smiled. He had a fantastic smile. He said, ‘I’m Dutch.’

I said, rudely, because I was so wildly excited, ‘You can’t be. Dutch boys aren’t tall, dark and handsome. Dutch boys are blond and look like potatoes.’

He laughed. Then he kissed me. Can you imagine being kissed by a total stranger and wanting him never to stop? And then we went for drinks, somewhere hot and dark and noisy, and then he said he’d got to go.

‘Go?’

‘To catch a plane.’

‘Where?’

‘Home. Back to Amsterdam.’

‘You can’t, you can’t—’

‘Come, too.’

‘I can’t. I’ve got a show to do—’

‘Come tomorrow.’

‘I can’t—’

‘Come.’

I looked at him. He looked back, like he was looking right into me, like he knew me. Then he picked up a paper serviette and wrote something on it.

‘Meet me there. Sunday. Three p.m.’

I peered at his scribble. ‘Can’t read it—’

‘Meet me,’ he said, ‘in front of my favourite painting. In the Rijksmuseum. Three o’clock Sunday.’

‘I’ve never been to Amsterdam—’

‘It’s easy,’ he said. ‘Everyone speaks English.’ He leaned forward and kissed me. ‘See you there, gorgeous.’

I said, ‘Can I have your number?’

He took my hands. He said, ‘No need. This is special. This is something else. This is a beginning.’

Of course, I went. I danced myself to a standstill in the Saturday matinee and the evening show, and when I came off stage, Sam, the stage manager, who could do praise as well as he could fly, said, ‘Nice work,’ looking straight at me. And then I went out of the theatre without a word to anyone and got a night bus to Stansted Airport and the first flight out to Amsterdam. I was so high on the thought of seeing him that you could have powered a city off me. Two, maybe.

That energy carried me through the night, through the next morning. It was like surfing a big wave that never quite got to shore. I bought coffee, I bought apple cake, I went brazenly into a big hotel and used the ladies’ room to wash and do my make-up and my hair. I talked to people and he was right, they spoke English, and they smiled, and they talked back to me. And at a quarter to three I was where he told me to be, in this huge old museum, crammed with visitors, standing in front of a painting of a boy with a big mop of frizzy hair and a face like a potato. Zelfportret ca. 1628, it said underneath. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn at twenty-two. I stared at him. He looked back out of his painting, over my shoulder as if he was waiting for someone.

He had a long wait. No one came. I waited two hours, and my Dutchman never came. I went out and drank gin, which there seems to be a lot of in Amsterdam, and got myself a weird hotel room near the station, and drank and cried and drank and cried until I fell asleep.

I went back the next day, in case he’d said Monday, not Sunday. And then I went back on Tuesday and Wednesday and Thursday. And, on Friday, something clicked in my brain, and I actually registered the messages on my phone, and a different sick fear slid down into my stomach. The fear of being let down was added to by the fear of losing my job.

‘Where the hell are you?’ Sam kept saying. He sounded furious. And then, ‘There are plenty more where you came from. Plenty.’

I don’t really want to talk about that journey home. You can imagine how I felt—we’ve all been there. We haven’t all been as stupid as to go all the way to Amsterdam to get there but we’ve all done the dumped, humiliated, disappointed, how-do-I-go-on thing. I looked at myself in my compact mirror as I sat on the bus from Stansted to London and I thought that nobody would ever fancy me again, and that if I were them I wouldn’t fancy me, either.

I got to the theatre early, about four-thirty, three hours to curtain up and nobody much in yet but the technicians. I went into the big dressing room that all us girls in the chorus shared and to my relief there was no one in there except Monica, who’d been cleaning up and calming down in that dressing room for about a hundred years. We called her Mon and sometimes, when we were tired or upset because we’d fluffed a move or got kicked on stage, we called her Mum by mistake and she never minded.

She was sweeping the floor. Clots of cotton wool and chocolate wrappers and hairballs. She stopped sweeping when I came in.

‘Where’ve you been?’

I slumped in a chair and looked at myself in a mirror with all those light bulbs round it. I said, ‘Amsterdam.’

She leaned her broom against the wall. ‘What for?’

I fished around in my bag and pulled out a postcard. I put it down in front of me. ‘To look at him.’

She came over. She smelled, as she always did, of fags and carnation soap. ‘And?’

‘It’s Rembrandt. When he was twenty-two.’

Monica said, ‘I know about Rembrandt.’

I said, ‘I’ve screwed up. I haven’t got a love life and I’ve lost my job.’

Monica looked at the postcard. ‘Twenty-two. How old are you?’

‘Twenty-three.’

She sucked her teeth.

I put my head down on my arms, on Rembrandt. I said, ‘What am I going to do?’

‘When he painted that painting,’ Monica said, ‘he didn’t know his future. Did he? He didn’t know he was going to be the greatest. He just knew he could paint. That he’d got to paint.’

‘I can’t paint,’ I said, into my arms.

‘You can dance,’ Monica said. ‘You can dance better than most of them. You can sing.’

‘Sam won’t let me. Not any more.’

‘You know,’ Monica said, ‘about Samuel Beckett?’

I lifted my head. My eyes and nose were red. ‘I’ve heard of him.’

‘He said, “You try, you fail, you try again, you fail better.” You’ve got to try. You’ve got a future to make. You’ve got to try.’

I sniffed.

‘Get up,’ she said. ‘Get up and get moving. Wash your face. Find Sam.’

Sam was on stage, with the techies. They were fixing something to do with the steps we had to come down, high kicking and singing. There were places where they didn’t feel too solid, those steps, and we used to shove each other about to avoid those places. I went and stood beside Sam. He had a clipboard. He didn’t look at me.

‘Push off,’ Sam said.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t move.

‘You heard me,’ Sam said.

‘I’m sorry—’

‘Too late,’ Sam said. ‘I’ve replaced you.’

I said, ‘I’m back.’

‘Without your Dutchman.’

I said, ‘They look like potatoes.’

He wrote something on his clipboard. Then he said, ‘At least I don’t look like a potato.’

I looked at him. He didn’t. He looked fine.

Sam shouted something at the techies. Then he said, ‘Go and get me a coffee.’

I went on looking at him. I said, ‘How d’you know about the Dutchman?’

‘I make it my business to know.’

‘About all of us?’

There was a beat.

‘No,’ Sam said.

‘I brought one back,’ I said. ‘A Dutchman. On a postcard. Rembrandt, when he was twenty-two. I don’t think I’ve ever looked at a man so long. I thought he looked like a potato but he doesn’t. He looks great.’

Sam shouted something else. He glanced at me. ‘I think I can cope with a postcard.’

I waited.

‘Go and get me a coffee,’ Sam said again.

‘Please.’

‘Please. Get two coffees.’

‘Two?’

He looked at me, red eyes, red nose, dirty hair. He said, very clearly, ‘Two coffees. One for you. One for me. Scoot.’

I felt my arms moving at my sides, like wings rising. Maybe I was going to hug him. He took a step away.

‘Scoot,’ he said.

‘But Sam—’

‘Scoot!’ he shouted, so all the techies could hear, and then he dropped his voice. ‘Don’t be long,’ he said. He smiled at me. He actually smiled. He had beautiful teeth. ‘Don’t be long.’

Nicola Cornick

Nicola Cornick studied history at London University and Ruskin College, Oxford, earning a distinction in her Masters degree with a dissertation on heroes and hero myths. She has a ‘dual life’ as a writer of historical romance for Harlequin Mills & Boon and a historian working for the National Trust. A double nominee for both the Romantic Novelists’ Association Romance Prize and the Romance Writers of America RITA award, Nicola has been described by Publishers Weekly as ‘a rising star of the Regency genre’. Her most recent book, Kidnapped, is available now from M&B Books. Her website is www.nicolacornick.com

The Elopement

It was a fact universally acknowledged in the village of Marston Priors that Amanda, Lady Marston, although young, was the unchallenged arbiter of good manners.

‘For,’ as Mrs Duke said to Mrs Davy, ‘if Lady Marston feels it is inappropriate to travel even the shortest distance in a carriage without one’s personal maid, I am sure that you will never see me defying convention by going out alone.’ Mrs Davy, who could not afford to employ a lady’s maid, agreed glumly.

Amanda Marston woke slowly and luxuriously that morning. She knew that the day was well advanced because Benson had drawn back the curtains and the spring sunshine was drawing out the rich and vivid colours from the beautiful new Axminster carpet. She knew she had an eye for design. It was one of her greatest accomplishments.

The scent of the hot chocolate lured her and she reached out a languid hand for the cup. Her fingers brushed the crisp parchment of a letter and she picked it up, still mulling over whether the bed drapes required refurbishment and whether pale green gauze might look dangerously like a harlot’s boudoir…Not that she knew anything of such things…

She read the first line of the letter with vague attention, the second with concentration and the third with outrage.

My dear Amanda

It is with great pleasure that I can inform you that I have eloped with Mr Sampson. I have always hankered after participating in an elopement so you may imagine my pleasure. I believe that the usual form of words on these occasions is: ‘Pray do not come after us.’ I am of age several times over and know my own mind, so there is no point in either you or Hugo trying to fetch me back. Indeed,

I hope you will both wish me happy.

Your loving grandmother-in-law, Eleanor Pevensey

Amanda shrieked, an action that startled her as much as it did the footman on the landing outside. Amanda never screamed, not even in a ladylike manner over a dead mouse or small spider. She had always considered having the vapours to be a vulgar way of attracting attention. Now, however, she shrieked again.

Lady Pevensey had eloped.

Lady Pevensey was entrusting herself and all her lovely fortune into the hands of a penniless curate.

Of all the outrages perpetrated by her husband’s seventy-seven-year-old grandmother, this was by far the most shocking. Lady Pevensey had been living at Marston Hall for six months and Amanda had found her a serious trial. Lady Pevensey rode to hounds, swore like a trooper and forgot all about visiting hours.

But none of these offences against propriety was as dreadfully scandalous as an elopement.

Amanda actually spilt drops of chocolate on the beautiful linen of her bedclothes. Never had she felt so overset, not even when the silk for her new evening gown had been quite the wrong shade of rose-pink.

She shoved the chocolate cup aside and tumbled from the bed, grabbing her swansdown-trimmed wrap and hurrying to the door that connected her room to that of her husband.

She turned the knob. The door was locked. She remembered that it had not been used in the past six months and only at very irregular intervals in the three years of her marriage. For some reason this state of affairs suddenly made her feel more than a little troubled.

She ran barefoot to the door onto the landing, only to be confronted by the footman, whose Adam’s apple bobbed with shock at the sight of her ladyship en déshabillée. Normally Lady Marston would not emerge from her room until she was immaculately attired. This was unprecedented.

‘Where is Lord Marston?’ Amanda demanded, waving the letter agitatedly in the footman’s face. ‘I require to speak with him immediately!’

The footman boggled. Lady Marston never required to know where her husband was, treating his whereabouts as a matter of utmost indifference. Red to the tips of his ears, he managed to stammer that Lord Marston had breakfasted several hours earlier and, he believed, was out on the estate.

‘Then pray send to find him,’ Amanda snapped, ‘and send for Crockett. At once!’

Choosing her morning outfit was usually one of Amanda’s favourite occupations but this morning she found that the merits of her cherry-red promenade dress or her pale yellow muslin did not interest her. She had grabbed a lilac gown when her maid arrived and dressed with a lack of care that startled the poor woman severely. When Crockett enquired how she would like her hair arranged, Amanda said, ‘I do not have the time!’ scooped up the letter and positively ran down the stairs.

Lord Marston had not yet been found but Amanda remembered vaguely that he had said something about his sheep at dinner the previous night and so she set off towards where she imagined the pastures might be. Following a mixture of bleating and hammering, she located Lord Marston a good mile away, by which time her dainty slippers were ruined and the hem of her lilac gown three inches deep in mud.

Amanda did not notice, however, for as she drew near she realised that it was Hugo himself who was hammering in fence posts. His jacket discarded, his rolled up shirtsleeves revealed strong, bronzed forearms. The muscles moved beneath his skin as he worked with grace and precision. Amanda, who had been about to exclaim over the inappropriateness of her husband undertaking manual work, discovered that her mouth was suddenly dry.

Hugo caught sight of her and straightened. In the spring sunshine his eyes gleamed vivid blue in his tanned face. He rubbed his brow and Amanda saw a drop of sweat run down the strong brown column of his neck. She should feel disgusted but suddenly there was a curl of something quite other than disgust in the pit of her stomach. Why had she never noticed before that Hugo was so attractive?

‘Amanda?’ Hugo came up to her and caught her elbow. The warmth of his hand seemed to burn through the silk of her gown. ‘What the devil are you doing here?’

His gaze, normally so inscrutable, slid from the tips of her muddy slippers to her flushed cheeks and lingered on the hair loose about her face. Suddenly there was something speculative and heated in his eyes that made Amanda feel even more light-headed. It was not the sort of look a man should give his wife of three years. She could not remember Hugo ever looking at her like that. It was not respectable. Nor was his bad language. But it seemed incredibly hard to drag her gaze away from his, let alone to correct him.

‘I…um…’ Amanda made a huge effort to remember why she had needed to talk to him. Lady Pevensey. She held out the letter. ‘Your grandmother, Hugo! The most disastrous thing! She has eloped with Mr Sampson! We simply have to stop her.’

Hugo dipped his head over the note, affording her a most enjoyable view of his broad shoulders under the damp linen of his white shirt. He wore an old pair of breeches that Amanda would normally have scorned. But how well they fitted his muscular thighs and what a fine figure he had. She blinked. What on earth was wrong with her? Lady Pevensey’s elopement had overset her nerves, of course, and running around in the sunshine without a bonnet was very bad for her. She needed to lie down in a darkened room.

With Hugo.

The thought slipped into her mind and she was so shocked that she blushed. She saw that Hugo was watching her, a quizzical smile in his eyes. Another curl of excitement lit her blood, only stronger than before. To cover her embarrassment she snapped, ‘Well? What are you going to do, Hugo? Your grandmother has run off with a man half her age!’

The smile did not fade from Hugo’s eyes. ‘I do not think you are quite correct there, my dear. Mr Sampson came late to ordination and I believe he is now in his sixties—’

‘He is still young enough to be her son,’ Amanda said. ‘And that is not the point, Hugo. The point is—’

‘That she is rich and we wanted her money and now there is a danger she will leave it to her new husband instead,’ Hugo finished.

Amanda gaped. ‘How very vulgar you sound!’

Hugo shrugged his broad shoulders. ‘Is that not what you meant, Amanda?’

Amanda struggled. ‘Well, I suppose…But I would not have put it so bluntly.’

‘Why not?’ Hugo’s smooth tones seemed to hold the very slightest hint of mockery. ‘We both know that Grandmama’s twenty thousand pounds would be most welcome.’

‘Yes,’ Amanda said, still struggling, ‘but I wish to save her from a terrible mistake.’

‘Rot,’ Hugo said cheerfully. ‘The only mistake you wish to save her from is leaving her money away from us!’

Amanda wondered whether too much fresh air had gone to Hugo’s head. He never normally spoke to her like this. Usually he was courteous to the point of indifference. She felt an unexpected pang at the thought.

‘You are mistaken,’ she said carefully. ‘I do not think it right for Lady Pevensey to marry a man even twenty years her junior.’

‘Because of the scandal.’

‘For her personal happiness!’ Amanda burst out, though admitting to herself that her husband was absolutely right.

‘Oh, I should not worry about that. Sampson is a fit and vigorous gentleman for his years. I imagine he will make her very happy.’

‘Hugo!’ Amanda was appalled, her mind awash with most inappropriate images of Lady Pevensey and her new husband disporting themselves in the bedroom.

‘I mean that they have a shared interest in hunting and the outdoors,’ Hugo said, ‘as well as a lively interest in more academic matters. That is more than many couples can boast. Whatever did you think I meant, Amanda?’

‘Nothing!’ Amanda shook her head slightly, trying to dispel the images and at the same time trying not to take too personally Hugo’s comment about couples who had nothing in common.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘since it seems I cannot persuade you to try to prevent this elopement, Hugo, I shall set out for Gretna Green immediately.’

Hugo gave a crack of laughter. ‘You? You do not even know where Gretna Green is!’