Полная версия

Listen to This

As Pruiksma explains, the sight of world cultures happily intermingling provided a mythological justification for Louis XIV’s marriage into the Spanish Habsburg family in 1660. Given the Hispanic origins of the chaconne, the music fit the occasion.

In these same years, the chaconne underwent its epic mutation, taking on a markedly more serious visage. Other dances of the day evolved in much the same way: the racy zarabanda became the stately sarabande, a medium of sober reflection for the likes of J. S. Bach and George Frideric Handel. Composers seemed to compete among themselves to see who could most effectively distort and deconstruct the popular music of the seventeenth century. They must have done so in a spirit of intellectual play, demonstrating how the most familiar stuff could be creatively transformed; such is the implicit attitude of Frescobaldi’s Partite sopra ciaccona and Cento partite. Louis Couperin, a keyboard composer of questing intellect, carried on the game by writing chaconnes that, in the words of Wilfrid Mellers, “proceed with relentless power, and are usually dark in color and dissonant in texture.” The same dusky aura hangs over a Chaconne raportée by the august viol player Sainte-Colombe, which, in a fusion of the chaconne and lamento traditions, begins with a lugubrious chromatic line.

English chaconnes, too, assumed both light and dark shades. The restoration of the English monarchy in the wake of Oliver Cromwell’s republican experiment called for musical spectaculars in the Lully vein, replete with sumptuous dances of enchantment and reconciliation. Several exquisite specimens came from the pen of Henry Purcell, the leading English composer of the late-seventeenth century. In his semiopera King Arthur, nymphs and sylvans in the employ of an evil magician attempt to lure the hero king with a gigantic passacaglia on a Lamento della ninfa bass. Purcell’s The Fairy Queen, a very free adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, culminates in a decorous, Lullyesque chaconne titled “Dance for Chinese Man and Woman.” (The play ends in a not very Shakespearean Chinese Garden.) In works of more intimate character, Purcell often reverted to the lachrymose manner of Dowland and other Elizabethan masters. The lamenting chromatic fourth worms its way through the anthem “Plung’d in the confines of despair” and the sacred song “O I’m sick of life.”

In 1689 or shortly before, Purcell produced the most celebrated ground-bass lament in history: “When I am laid in earth,” Dido’s aria at the end of the short opera Dido and Aeneas. Could Purcell have known Cavalli’s Didone? Probably not, but he did make unforgettable use of the same chromatic-ostinato device that Cavalli implanted in Hecuba’s song. Purcell takes care first to introduce the bass line on its own, so there is no mistaking its expressive role. This is from an eighteenth-century copy:

The notes are like a chilly staircase stretching out before one’s feet. In the fourth full bar there’s a slight rhythmic unevenness, a subtle emphasis on the second beat (one-two-three). You can hear the piece almost as an immensely slow, immensely solemn chaconne. Nine times the ground unwinds, in five-bar segments. Over it, Dido sings her valediction, a blanket of strings draped over her:

When I am laid in earth, may my wrongs create

No trouble in thy breast,

Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

The vocal line begins on G, works its way upward, and retreats, with pointed repetitions of the phrases “no trouble” and “remember me.” Dido’s long lines spill over the structure of the ground, so that she finds herself arching toward a climactic note just as the bass returns to the point of departure. First she reaches a D, then an E-flat. With the final “remember me” she attains the next higher G, the “me” falling on the second beat. When the song is done, there is a debilitating chromatic slide, undoing, step by step, the effort of the ascent. The ostinato of fate seems triumphant. Yet Dido’s high, brief cry is the sound we remember—a Morse-code signal from oblivion.

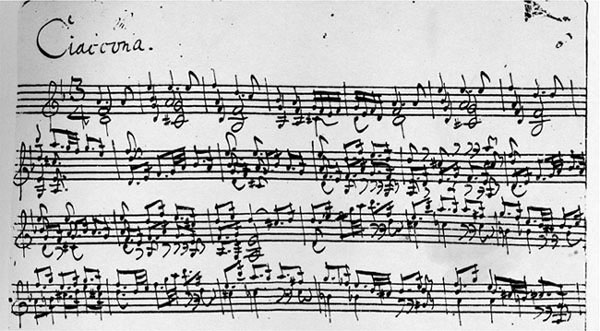

CIACCONA IN D MINOR

Bach’s Ciaccona for unaccompanied violin, a quarter-hour-long soliloquy of lacerating beauty, stands at such a distance from the hijinks of the Spanish chacona that the title seems almost ironic. With its white-knuckle virtuosity, its unyielding variation structure, and its tragic D-minor cast, this is a piece from which la vida bona appears to have been banished utterly. Yet the ghost of the dance hovers in the background. The image of Bach as a bewigged, sour-faced lawgiver of tradition has caused both performers and listeners to neglect the physical dimension of his work. To hear the Ciaccona played on the guitar—there are richly resonant recordings by Andrés Segovia and Julian Bream—is to realize that bodily pleasure has its place even in the blackest corners of Bach’s world.

Bach made his name as an organist, joining a starry lineage of northern European organ players that went back to the Dutch composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621). Sweelinck, in turn, drew on the tortuous chromatic techniques of late-Renaissance Italy and Elizabethan England. In his Fantasia chromatica, Sweelinck subjects a descending chromatic figure and two companion themes to various contrapuntal manipulations, forming a spidery mass of intersecting lines. The finger-twisting brilliance of the writing is held in check by a taut tripartite scheme: in the first third, the theme proceeds at a regular tempo; in the second, it is slowed down; in the third, it goes faster and faster still. Such music marks the beginning of the Bachian art of the fugue.

The organists of the German Baroque, who included Dietrich Buxtehude and Johann Pachelbel, embraced the practice of “strict ostinato,” in which a short motif repeats in the bass while upper voices move about more freely. (The inescapable Pachelbel Canon is an ostinato exercise in a lulling major key.) The interplay between independent treble and locked-in bass acquires additional drama when the bass lines are bellowed out on the organ’s pedal notes—sixteen- and even thirty-two-foot pipes activated by the feet. Bach’s Passacaglia in C Minor, a looser kind of ostinato piece, begins with the bass alone, in a pattern that winds upward from the initial C before spiraling down an octave and a half to a bottom C that should be heard less as a note than as a minor earthquake. Bach was especially attracted to bass lines that crawled along chromatic steps. One of these shows up in the third movement of the playful little suite Capriccio on the Departure of a Beloved Brother, one of Bach’s earliest extant works. In the 1714 cantata “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen,” a corkscrew chromatic bass portrays the “weeping, wailing, fretting, and quaking” of Christ’s followers.

When, in 1723, Bach took up the position of cantor at St. Thomas School in Leipzig, he pledged that his music would be “of such a nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion.” In employing Italian opera devices such as the lamento bass, he might have been trying to sublimate them, taming a dangerously sultry form. A man of religious convictions, Bach wrote in the margins of his favorite Bible commentary that music was “ordered by God’s spirit through David” and that devotional music showed the “presence of grace.” At the same time, though, his arioso melodies had the potential to undermine the austerity of the Lutheran service; even if he never wrote an opera, he displayed operatic tendencies. He presumably understood these contradictions, and possibly relished them. His comment about the “presence of grace” pertained to a faintly occult description of music-making at the Temple, in the second book of Chronicles: “It came even to pass, as the trumpeters and the singers were as one, to make one sound to be heard in praising and thanking the Lord … The house was filled with a cloud, even the house of the Lord.”

The Ciaccona for solo violin, which Bach composed in 1720 as part of his cycle of Sonatas and Partitas, possesses something like that ominous, cloudlike presence. It takes the form of sixty-four variations on a four-bar theme in D minor, with each four-bar segment generally repeated before the next variation begins. But the melodic strands of the opening bars—both treble and bass—disappear for long stretches as Bach explores new material. The “theme” is really a set of chords, framing limitless flux. (The copy reproduced on the previous page was probably made not long after Bach’s death.) Lament figures crop up throughout, sometimes plainly presented and sometimes hidden in the seams. A D-major middle section functions as a respite from the prevailing gloom of the piece, yet the apparition of a descending chromatic line high in the treble hints that these brighter days won’t last. Soon after, D minor returns, with a four-note lament motif planted firmly in the bass—the shade of “Fors seulement,” Lachrimae, and Lamento della ninfa.

It would appear that Bach has gone beyond rituals of mourning to a solitary, existential agony. In the words of Susan McClary, “the lone violinist must both furnish the redundant ostinato and also fight tooth and nail against it.” For McClary, the chaconne has become a formal prison for the struggling self. But Bach hasn’t entirely forgotten the sway of the dance. Alexander Silbiger, in a revealing essay, draws attention to passages of “repeated strumming,” “rustling arpeggiations,” “sudden foot-stamping.” Often Bach tests the limits of his variation scheme and lands back in D minor with a precarious lunge: “Some of these ventures bring to mind a trapeze artist, who swings further and further, reaching safety only at the last instant and leaving his spectators gasping.” The violin’s more florid gestures also make Silbiger think of jazz artists and sitar players, who “create the illusion of taking momentary flight from the solid ground that supports their improvisations, to the occasional bewilderment of their fellow performers.” In the end, the Ciaccona might be a grave dance before the Lord, the ballet of the soul in the course of a life.

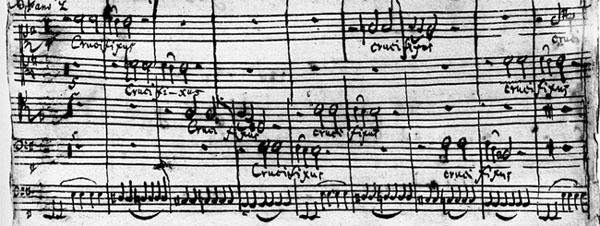

In 1748 and 1749, the last full years of his earthly existence, Bach assembled his Mass in B Minor, rearranging extant works and writing new material in a quest for a comprehensive union of Catholic and Lutheran traditions. At the heart of the Mass is the section of the Credo that deals with the death of Jesus Christ on the cross:

Crucifixus etiam pro nobis He was also crucified for us

sub Pontio Pilato, passus under Pontius Pilate, suffered,

et sepultus est. and was buried.

To find music for this text, Bach went back thirty-five years in his output, to the “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen” chorus, with its twelve somber soundings of a chromatic bass. But he stepped up the pulsation of the ground, so that instead of three half notes per bar we hear a faster, tenser rhythm of six quarter notes per bar. He changed the instrumentation, adding breathy flutes to tearful strings. He inserted a brief instrumental prelude, so that, as in Purcell, we first hear the bass line without the voices. Bach thus expanded the structure from twelve to thirteen parts. Whether he intended any symbolism in the number thirteen is unknown, although most of his listeners would have been aware that the Last Supper had thirteen guests. This is in Bach’s own hand:

As in Didone and Dido and Aeneas, the chromatic pattern evokes an individual pinned down by fate. This time, the struggler is not a woman but a man, one who knows full well what fate has in store. Bach makes Jesus Christ seem pitiably human at the moment of his ultimate suffering, so that believers may confront more directly their own grief and guilt. (Martin Luther vilified the Jews, but he also preached that Christians should hold none but themselves responsible for Christ’s killing.) It is a quasi-operatic scene, although it is witnessed at a properly awed distance. The voices wend away from the bass, moving in various directions. There are slowly pulsing chords of strings on the first and third beats, flutes on the second and third: they suggest something dripping, perhaps blood from Christ’s wounds, or tears from the eyes of his followers. In the thirteenth iteration, the bass singers give up their contrary motion and join the trudge of the continuo section. The sopranos, too, follow a chromatic path. The upper instruments fall silent, as if the dripping has stopped and life is spent. Fate’s victory seems complete. But then the bass suddenly reverses direction, and there is a momentous swerve from E minor into the key of G major. On the next page, the Resurrection begins.

ROMANTIC VARIATIONS

Bach died in 1750, and the Baroque era more or less died with him. Forms of rigid repetition lost their appeal as the Baroque gave way to the Classical period and then to the Romantic: increasingly, composers valued constant variation, sudden contrast, unrelenting escalation. Music became linear rather than circular, with large-scale structures proceeding from assertive thematic ideas through episodes of strenuous development to climaxes of overwhelming magnitude. “Time’s cycle had been straightened into an arrow, and the arrow was traveling ever faster,” the scholar Karol Berger writes. Music would no longer react to an exterior order; instead, it would become a kind of aesthetic empire unto itself. In 1810, E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote a review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in which he differentiated the Romantic ethos from the more restrained spirit of prior centuries: “Orpheus’s lyre opened the gates of Orcus. Music reveals to man an unknown realm, a world quite separate from the outer sensual world surrounding him, a world in which he leaves behind all feelings circumscribed by intellect in order to embrace the inexpressible.”

For composers of Mozart’s time and after, the chaconne, the passacaglia, and the lamento aria would have been antique devices learned from manuals of counterpoint and the like. Yet they never disappeared entirely. Beethoven studied Bach in his youth, and at some point he came across the B-Minor Mass, or a description of it; in 1810 he asked his publisher to send him “a Mass by J. S. Bach that has the following Crucifixus with a basso ostinato as obstinate as you are”—and he wrote out the “Crucifixus” bass line. Beethoven was undoubtedly thinking of Bach when, in his Thirty-two Variations in C Minor of 1806, he elaborated doggedly on the downward chromatic fourth. Eighteen years later, a “Crucifixus” figure cropped up in the stormy D-minor opening movement of the Ninth Symphony. Thirty-five bars before the end, the strings and bassoons churn out a basso lamento that has the rhythm of a dirge: you can almost hear the feet of pallbearers dragging alongside a hero’s casket.

Yet the ostinato is a nightmare from which Beethoven wishes to wake. The finale of the Ninth rejects the mechanics of fateful repetition: in the frenzied, dissonant music that opens the finale, the chromatic descent momentarily resurfaces, and when it is heard again at the beginning of the vocal section of the movement the bass soloist intones, “O friends, not these tones!” At which point the Ode to Joy begins. Beethoven might have been echoing the central shift of the B-Minor Mass—the leap from the chromatic “Crucifixus” to the blazing “Et resurrexit.”

The lamento bass would not stay buried. It rumbles in much music of the later nineteenth century: in various works of Brahms, in the late piano music of Liszt, in the songs and symphonies of Mahler. It is a dominating presence in Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony, which ends with a slow movement marked Adagio lamentoso. Even in the first bars of the first movement, double basses creep down step by chromatic step while a single bassoon presses fitfully upward. (The scenario is much like the contrary motion of the upper and lower voices in Dido’s Lament.) The final Adagio begins with a desperately eloquent theme that contains within it the time-worn contour of folkish lament. In the coda, Tchaikovsky combines the modal and chromatic forms of the lamento pattern, creating a hybrid emblem of grief, somewhat in the manner of Bach’s chaconne. The passage plays out over a softly pulsing bass note that recalls the eternal basses of Bach’s Passions.

The affect of the Adagio lamentoso could hardly be clearer. Tchaikovsky seems to have reverted to the mimetic code of Renaissance writers such as Ficino: as the music droops, so droops the heart, until death removes all pain. Indeed, the tone of lament is so fearsomely strong that many listeners have taken it to be a direct transcription of Tchaikovsky’s own feelings. The work had its premiere nine days before the composer’s sudden death, of cholera, in 1893, and almost immediately people began to speculate that it was a conscious farewell. Wild rumors circulated: according to one tale, Tchaikovsky had committed suicide at the behest of former schoolmates who were scandalized by his homosexuality. That last story is a fascinating case of musically induced hallucination, for the biographer Alexander Poznansky has established that no such plot could have existed and that Tchaikovsky was actually in good spirits before he fell ill. The Pathétique is best understood not as a confession but as a riposte to Beethoven’s heroic narrative, the progression from solitary struggle to collective joy. In the vein of Dowland, Tchaikovsky asserts the power of the private sphere—the contrary stance of the happily melancholy self. Indeed, lament has never made so voluptuous a sound.

THE LIGETI LAMENTO

In the twentieth century, time’s arrow again bent into a cycle, to follow Karol Berger’s metaphor. While some composers pursued ever more arcane musics of the future, others found a new thrill in archaic repetition. Chaconne and related forms returned to fashion. Schoenberg, hailed and feared as the destroyer of tonality, actually considered himself Bach’s heir, and his method of twelve-tone writing, which extracts the musical material of a piece from a fixed series of twelve notes, is an extension of the variation concept. (So argued Stefan Wolpe, an important Schoenberg disciple, in an essay on Bach’s Passacaglia in C Minor.) “Nacht,” the eighth song of Schoenberg’s melodrama Pierrot lunaire, is subtitled “Passacaglia,” its main theme built around a downward chromatic segment. The revival of Baroque forms quickened after the horror of the First World War, which impelled young composers to distance themselves from a blood-soaked Romantic aesthetic. The circling motion of the chaconne and the passacaglia also summons up a modern kind of fateful loop—the grinding of a monstrous engine or political force. In Berg’s Wozzeck, a passacaglia reflects the regimented madness of military life; in Britten’s Peter Grimes, the same form voices the mounting dread of a boy apprentice in the grip of a socially outcast fisherman.

No modern composer manipulated the lament and the chaconne more imaginatively than György Ligeti, whose music is known to millions through Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Indeed, Ligeti inspired the present essay. In 1993, I heard the composer give a series of dazzlingly erudite talks at the New England Conservatory, in Boston, during which he touched many times on the literature of lament. At one point Ligeti sang the notes “La, sol, fa, mi”—A, G, F, E, the Lamento della ninfa bass—and began cataloguing its myriad appearances in Western music, both in the classical repertory and in folk melodies that he learned as a child. He remembered hearing the bocet in Transylvania: “I was very much impressed by these Romanian lamentos, which old women sing who are paid when somebody is dead in a village. And maybe this is some musical signal which is very, very deep in my subconscious.” He noted a resemblance between Eastern European Gypsy music and Andalusian flamenco. He also spoke of Gesualdo’s madrigals, Purcell’s “When I am laid in earth,” Bach’s “Crucifixus,” and Schubert’s Quartet in G Major—about which more will be said in a later chapter.

Ligeti first encountered the older repertory while studying at the Kolozsvár Conservatory, in the early 1940s. The Second World War interrupted his schooling: after serving in a forced-labor gang, he returned home to discover that many of his relatives, including his father and his brother, had died in the Nazi concentration camps. His first major postwar work, Musica ricercata for piano (1951–53), dabbled in various Renaissance and Baroque tricks; the final movement, a hushed fugue, draws on one of Frescobaldi’s chromatic melodies. After leaving Hungary, in 1956, Ligeti entered his avant-garde period, producing scores in which melody and harmony seem to vanish into an enveloping fog of cluster chords, although those masses of sound are in fact made up of thousands of swirling microscopic figures. In the 1980s, Ligeti resumed an eccentric kind of tonal writing, in an effort to engage more directly with classical tradition; perhaps he also wished to excavate his tortured memories of the European past. The finale of his Horn Trio is titled “Lamento”; at the outset, the violin softly wails in a broken chromatic descent. Although the motif recurs in chaconne style, this is a somewhat unhinged ceremony of mourning, its funereal tones giving way to outright delirium. In the climactic passage, the three instruments execute musical sobs in turn, as if mimicking village cries that Ligeti heard as a child.

In the last phase of his career, Ligeti devised his own lament signature. Richard Steinitz, the composer’s biographer, defines it as a melody of three falling phrases, dropping sometimes by half-steps and sometimes by wider intervals, with the note of departure often inching upward in pitch and the final phrase stretching out longer than the previous two. That heightening and elongating of the phrases is another memory of folk practice. The Ligeti lamento cascades through all registers of the piano etude “Automne à Varsovie”; it also figures in several recklessly intense passages of the Violin Concerto (whose fourth movement is a Passacaglia) and of the Piano Concerto. And in the Viola Sonata, chaconne and lament once again intersect. The final movement of the sonata is titled “Chaconne chromatique,” and the rhythm of the principal theme—short-long, short-long, short-short-short-short long—recalls the languid motion of Dido’s Lament. Then the motif begins to accelerate, becoming, in Steinitz’s words, “fast, exuberant, passionate.” As in Hungarian Rock, Ligeti’s rollicking chaconne for harpsichord, the specter of the old Spanish dance returns, writhing behind a modernist scrim.

THE BLUES

In 1903, the African-American bandleader W. C. Handy was killing time at a train depot in Tutwiler, Mississippi—a small town in the impoverished, mostly black Mississippi Delta region—when he came upon a raggedly dressed man singing and strumming what Handy later described as “the weirdest music I had ever heard.” The nameless musician, his face marked with “the sadness of the ages,” kept repeating the phrase “Goin’ where the Southern cross’ the Dog,” and he bent notes on his guitar by applying a knife to the strings. The refrain referred to the meeting point of two railway lines, but it conjured up some vaguer, supernatural scene. Handy tried to capture the phantom singer of Tutwiler in such numbers as “The Memphis Blues,” “The Yellow Dog Blues,” and “The St. Louis Blues.” The last, in 1914, set off an international craze for the music that came to be known as the blues.