Полная версия

Listen to This

After reaching a peak of refinement in the works of Ockeghem’s disciple Josquin Desprez, polyphony faded in importance in the later sixteenth century. Listeners demanded new, often simpler styles. The marketplace for music expanded dramatically, with the printing press fostering an international, nonspecialist public. Dance fads such as the chaconne indicated the growing vitality of the vernacular. The Church, shaken by the challenge of the Reformation and its catchy hymns of praise, saw the need to make its messages more transparent; the Council of Trent decreed that church composers should formulate their ideas more intelligibly, instead of giving “empty pleasure to the ear” through abstruse polyphonic designs.

For a host of reasons, then, emotion in music became a hot topic. The theorist Gioseffo Zarlino, in his 1558 text Le istitutioni harmoniche, instructed composers to use “cheerful harmonies and fast rhythms for cheerful subjects and sad harmonies and grave rhythms for sad subjects.” Zarlino went on: “When a composer wishes to express effects of grief and sorrow, he should (observing the rules given) use movements which proceed through the semitone, the semiditone, and similar intervals”—a reference to the sinuous chromatic scale, which had long been discouraged as musically erroneous but which in these years became a modish thing. Various scholars promoted the idea of a stile moderno, or “modern style”—music strong in feeling, alert to the nuances of texts, attentive to the movement of a singing voice.

The passions of the late Renaissance primed the scene for opera, which emerged in Italy just before 1600. In the decades leading up to that breakthrough, the great laboratory of musical invention was the madrigal—a secular polyphonic genre that allowed for much experiment in the blending of word and tone. While early madrigals tended to be straightforwardly songful, later ones were at times willfully convoluted, comparable in spirit to Mannerist painting. High-minded patrons encouraged innovation, even an avant-garde mentality; the dukes of Ferrara commissioned a repertory of musica secreta, or “secret music.” The arch-magus of musical Mannerism was Carlo Gesualdo, a nobleman-composer who put forward some of the most harmonically peculiar music of the premodern epoch. His madrigal Moro lasso—“I die, alas, in my grief”—begins with a kaleidoscopic sequence of chords pinned to a four-note chromatic slide; Dolcissima mia vita ends with a briar patch of chromatic lines around the words “I must love you or die.” The words are ironic in light of Gesualdo’s personal history: in 1590, he discovered his wife in bed with another man and had both of them slaughtered.

The madrigal fad spread to England, where Elizabethan intellectuals were raising their own banners of independence. Drowning oneself in sorrow was one way of resisting the outward hierarchy of late-Renaissance society, the beehive ideal of each human worker performing his assigned task. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which was first performed around 1601, is the obvious case in point. The grief of the Prince of Denmark shines like a grim lantern on Claudius’s rotten kingdom, exposing not only Hamlet’s private loss but the hollowness of all human affairs: “I have that within, which passeth show; / These, but the trappings and the suits of woe.” Music was a favorite site for brooding in the Danish style. The composer Thomas Morley set down some guidelines in his 1597 textbook A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke: “If [the subject] be lamentable, the note must goe in slow and heavy motions, as semibriefs, briefs, and such like … Where your dittie speaketh of descending, lowenes, depth, hell, and others such, you must make your musick descend.” This echoed Zarlino’s literal-minded directive of 1558. In Elizabethan England, an inordinate number of ditties spoke of lowness, depth, and hell, leaving the heavenly register somewhat neglected.

The supreme melancholic among English composers was the lutenist John Dowland. Like so many of his international colleagues, Dowland indulged in chromatic esoterica, but he also showed a songwriter’s flair for hummable phrases: his lute piece Lachrimae, or Tears, achieved hit status across Europe in the last years of the sixteenth century. When, in 1600, Dowland published his Second Book of Songs, he included a vocal version of Lachrimae, with words suitable for a Hamlet soliloquy:

Flow my tears, fall from your springs,

Exil’d forever let me mourn

Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.

The first four notes of the melody have a familiar ring: they traverse the same intervals—whole tone, whole tone, semitone—that usher in Ockeghem’s “Fors seulement.” Underscoring the personal significance of the theme, Dowland made it the leitmotif of his 1604 cycle of pieces for viol consort, also titled Lachrimae.

In Dowland’s instrumental masterpiece, no reason for the flow of tears is given, no biblical or literary motive. Music becomes self-sufficient, taking its own expressive power as its subject. Lachrimae could have been cited as an illustration in Robert Burton’s 1621 treatise The Anatomy of Melancholy, which meditates on music’s capacity to conquer all human defenses: “Speaking without a mouth, it exercises domination over the soul, and carries it beyond itself, helps, elevates, extends it.” Music might inject melancholy into an otherwise happy temperament, Burton concedes, but it is a “pleasing melancholy.” That phrase encapsulates Dowland’s aesthetic. His forlorn songs have about them an air of luxury, as if sadness were a place of refuge far from the hurly-burly, a twilight realm where time stops for a while. The Lachrimae tune becomes, in a way, the anthem of the eternally lonely man. Indeed, as the musicologist Peter Holman points out, Dowland anticipated Burton’s thought in the preface to his collection: “No doubt pleasant are the tears which Musicke weepes.”

It has long been understood that music has the ability to stir feelings for which we do not have a name. The neurobiologist Aniruddh Patel, in his book Music, Language, and the Brain, lays out myriad relationships between music and speech, and yet he allows that “musical sounds can evoke emotions that speech sounds cannot.” The dream of a private kingdom beyond the grasp of ordinary language seems to have been crucial for the process of self-fashioning that so preoccupied Renaissance intellectuals: through music, one could make an autonomous, unknowable self that stood apart from the order of things. In a wider sense, Dowland forecast the untrammeled emotionalism of the Romantic era, and even the moodier dropout anthems of the 1960s, the likes of “Nowhere Man” and “Desolation Row.” As Oscar Wilde wrote of Hamlet, “The world has become sad because a puppet was once melancholy.”

OPERA

In 1589, Ferdinando de’ Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany, married Christine of Lorraine. The duke had acquired his title two years earlier, after the sudden demise of his older brother, Francesco. Modern analysis has confirmed what rumor long held: Francesco died of arsenic poisoning. Against this suitably sinister backdrop the art of opera arose. For decades, Medici festivities had offered dramatic musical interludes within a larger theatrical presentation. These intermedi, as they were called, grew ever more extravagant as the century went on, serving, in the words of the poet Giovanni Battista Strozzi the Younger, to “stun the beholder with their grandeur.” The play accompanied the music rather than the other way around. The writers and composers of Florence eventually decided to let the music run continuously. It was a new kind of sung drama, modeled on the theater of ancient Greece.

The first true opera was apparently Jacopo Peri’s Dafne, presented in Florence in 1598, with a text by Ottavio Rinuccini. Two years later, for another Medici wedding, Peri set Rinuccini’s Euridice, telling of the unhappy adventures of the poet and musician Orpheus. In a preface to the score, Peri announced the ascendancy of “a new manner of song,” through which grief and joy would speak forth with unusual immediacy. Peri’s chief rival, the singer-composer Giulio Caccini, wrote an opera on the same Euridice libretto not long after, and managed to get his version into print first. Claudio Monteverdi, an ambitious younger composer from Cremona, trumped them both with his five-act opera Orfeo, which had its premiere in 1607, at the court of the Gonzagas in Mantua, and which still holds the stage more than four centuries later.

Without the lament, opera might never have caught fire. The story of Orpheus is little more than a string of lamentations: the bard bewails the loss of Euridice, goes down into the underworld to rescue her (his plaint wins Hades over), and then, with one ill-timed backward glance, loses her again. Both Euridice operas, despite their tacked-on happy endings, perform familiar gestures of musical weeping. Peri briefly applies the falling four-note figure to Orpheus’s words “Chi mi t’ha tolto, ohime” (“Who has torn you from me, alas”). There’s a noteworthy expansion of the motif in Caccini’s treatment of the same text. After Orpheus finishes his lament, a nymph and various other voices echo him, bemoaning “Cruel death.” Caccini’s version is slower and grander than Peri’s, making more deliberate use of repetition. Seven times the chorus sings the formula “Sospirate, aure celesti, / lagrimate, o selve, o campi” (“Sigh, heavenly breezes / Weep, o forests, o fields”), with four-note laments threaded through the voices. The spaciousness of the sequence seems essentially operatic.

The next step was to back away from aristocratic refinement and incorporate elements of popular song and dance. Spain served as a primary source. Back in 1553, the viol player Diego Ortiz published a set of improvisations over a repeating bass line—a basso ostinato, or ground bass. The art of improvising on an ostinato went back centuries, although it had gone largely undocumented in notated music. When composers finally took hold of it, the effect was exhilarating, as if someone had switched on a rhythmic engine. Renaissance harmony in all its fullness was wedded to the dance. As Richard Taruskin observes, in his Oxford History of Western Music, this mammoth event—the birth of modern tonal language—was a revolution from below. A “great submerged iceberg” of unrecorded traditions, in Taruskin’s phrase, came into view, not least because publishers realized there was money in it.

The chaconne was one such bass-driven dance. The first major composer to impose his personality on the form was the magisterial Italian organist Girolamo Frescobaldi, another beneficiary of the largesse of the dukes of Ferrara. In 1627, Frescobaldi published Partite sopra ciaccona, or Variations on the Chaconne, in which the popular formula is sent through the compositional wringer: the bass line breaks away from its mold, the rhythmic pulse speeds up and slows down, and the harmony darkens several times from major to minor, with a spooky dissonance piercing the texture just before the end. Frescobaldi also wrote Partite on a related ostinato dance, the passacaglia, holding to the minor mode until the very end. (Chaconnes were generally in major keys and passacaglias in minor ones, although composers enjoyed subverting the rule.) A decade later, Frescobaldi upped the ante with his Cento partite, a dazzling sequence of one hundred variations that includes both passacaglias and chaconnes. In the words of the scholar Alexander Silbiger, Cento partite is “a narrative of the flow and unpredictability of human experience.” It deserves comparison with Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, and other consummate displays of compositional virtuosity.

Monteverdi, the reigning Italian master, appropriated the chaconne at around the same time. Although he held the lofty title of maestro di cappella, or director of music, at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice, he never lost his ear for the music of the streets. A rocketing chaconne propels the 1632 duet Zefiro torna, on a Rinuccini text:

Zephyr returns and blesses the air

with his soft perfume, draws bare feet to the shore,

and, murmuring among the green branches,

makes the flowers dance in the meadows to his pretty tune.

The buoyant rhythm neatly captures Rinuccini’s springtime imagery. The voices imitate one another and tease against the beat, like dancers weaving around a maypole. In the final lines, the sonnet takes a surprising turn: the protagonist of the poem reveals himself to be a disconsolate loner, singing and weeping over the absence of two fair eyes. And the bouncing beat gives way to a heaving lament. As in Lorca’s flamenco, sobs and kisses, pleasure and anguish, coincide.

Zefiro torna was a certifiable hit of the 1630s, grabbing the attention of many rival composers. Monteverdi deployed ostinato basses in several other pieces, most memorably in Lamento della ninfa, or Lament of the Nymph, which he published in his Eighth Book of Madrigals, of 1638. In an introduction to the volume, Monteverdi declared that he wished to give a complete musical picture of what he called the three passions—“anger, temperance, and humility or supplication.” Anger, he said, had never been properly depicted in music before, and he proudly underlined the groundbreaking achievement of his “madrigals of war.” But the Lamento is no less inventive in the way it goes about illustrating the third passion, that of the humbled soul. A solo female voice, representing a distraught nymph, sings a plaint—

Let my love return to me

as he was before

or take me then and kill me

so I rack myself no more.

—while three male voices paraphrase her woe (“unhappy one, ah, no more, she cannot suffer so much ice”). The bass line follows the classic lamenting shape. The notes A-G-F-E are heard thirty-four times in succession, never yielding.

The ostinato in Zefiro torna exudes a giddy, carefree air. The one in Lamento della ninfa is different. First, obsessive repetition focuses and magnifies the melancholy affect of the stepwise descent. Indeed, as the musicologist Ellen Rosand maintains, this work made the association almost official; the falling motif became an “emblem of lament,” one that composers employed consciously, with reference to Monteverdi’s model. Second, the ostinato has a symbolic function, carrying a tinge of psychological compulsion. The voice keeps tugging against the bass line, pushing upward, stretching its phrases beyond the two-bar unit, giving rise to dissonant clashes, breaking down into chromatic steps. The implacability of the bass suggests that these attempts at escape are in vain. Instead, the piece ends in a mood of shattered acquiescence, as the voice subsides to the note from which it began. Even so, there is no denying the seduction of repetition, the psychic pull of the circling motion. The ceremony of lament interrupts the ordinary passage of time, and therefore, paradoxically, holds mortality at bay.

In the early seventeenth century, opera spread across Italy, becoming more of a commercial entertainment in the process. In 1637, one year before Monteverdi published Lamento della ninfa, a touring troupe brought opera to the republic of Venice. The season took place during Carnival, the time of dissolution and self-reinvention. Opera was reborn as a many-layered, stylistically ravenous form, combining lyric tragedy with lewd comedy—the musical counterpart of the high-low drama of Shakespeare and Lope de Vega. Mythological subjects took on a modern edge; castrato singers flamboyantly restyled classical heroes; star divas enacted scenes of madness and lament; and a diverse public showed lusty approval. For the remainder of the century, up to five theaters were operating in Venice at one time, drawing an audience that included not only the upper crust but also courtesans, tourists, well-born students, and a smattering of ordinary people. In Ellen Rosand’s words, “opera as we know it assumed its definitive identity.”

Monteverdi was nearly seventy when opera came to Venice, but the phenomenon allowed him to experience a second youth. His two surviving late operas, The Return of Ulysses and The Coronation of Poppea, revel in extreme emotions, oscillating between suicidal angst and orgiastic joy. The two extant scores of Poppea—a drama of lust and greed in the high Roman Empire—both end with a disarmingly blissful duet between Nero and his lover Poppea, “Pur ti miro” (“I gaze upon you”), over a caressing major-key ground bass. Although scholars now believe that this duet was added by another composer, it communicates the heady allure of opera in its early days.

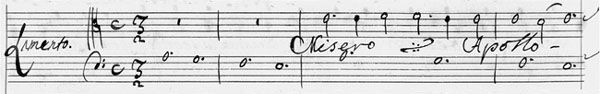

When Monteverdi died, in 1643, Francesco Cavalli, a gifted protégé, took his place. No less than his mentor had, Cavalli shaped the opera genre as we know it today, perfecting the transition from speechlike recitative to fully lyrical arioso singing. He had a particular gift for arias of lament, embedding them in velvety harmonic progressions. An early example appears in the 1640 opera Gli amori d’Apollo edi Dafne, which tells of Daphne’s transformation into a laurel tree. Toward the end, the god Apollo realizes that his beloved nymph has slipped from his grasp, and he declares himself miserable. Cavalli promptly unfurls the A-G-F-E bass line from Lamento della ninfa, making it the motor of a truncated arioso passage that bears the title Lamento:

As in Monteverdi, the repetition in the bass mimics the obsessive, circular thinking of the unhappy lover—the painful recollection of happy moments, the sick-hearted imagining of alternate outcomes. It follows the psychological rhythm of depression: the spirit sinking step by step, straining to recover, then sinking again.

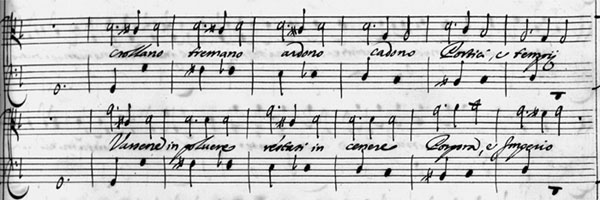

The Venetian public evidently enjoyed Apollo’s monologue of misery, for Didone, Cavalli’s opera for the following season, features laments galore. In the first act, survivors of the fall of Troy—Hecuba, King Priam’s widow; her daughters Cassandra and Creusa; and the hero Aeneas, Creusa’s husband—bewail the end of their world even as more mayhem descends on them. Cassandra has hardly finished mourning for her beloved Coroebus when Creusa is abruptly slain. Hecuba enters, seeking to voice a feeling “beyond the tears,” and she finds release in an incantation that seems to portray not only the recent fall of Troy but also the future demise of Greece:

Porticos, temples are

Shaking and trembling,

Burning and tumbling.

Purple and empire,

Turn into dust,

Make clothes of ashes!

At this point Cavalli had a stroke of genius, one that reverberated through the centuries. He prolonged Monteverdi’s ostinato bass, so that it moved down by chromatic steps (G–F-sharp–F-natural–E–E-flat–D). There’s something claustrophobic about those close-set intervals: they give the feeling of a dismal shuffle, the gait of a lost soul.

The laments of Didone come mainly from the throats of women: Cassandra and Hecuba in the first act, Dido at the end. Almost from the start, male opera composers depended on the figure of the abandoned, vengeful, and/or maddened female. The musicologist Susan McClary, in her pioneering study Feminine Endings, identifies Monteverdi’s Lamento della ninfa as a harbinger of operatic mad scenes, describing the piece as “a display designed by men, chiefly for the consumption of other men.” McClary compares the music to a grille on an old asylum window through which passersby could watch mad people. Other scholars, though, have detected a certain defiant self-assertion in the female portraits set forth by Cavalli and other early operatic composers. Wendy Heller, in a discussion of Didone, describes the title character as a tragically constrained woman, but celebrates Hecuba as an intriguingly dangerous force of nature, her music charged with “a sense of the supernatural and the other-worldliness of [her] strength.”

The singer and composer Barbara Strozzi (1619–77), one of the few publicly recognized female composers of the Baroque period, reversed the standard equation in her cantata L’Eraclito amoroso (“The Amorous Heraclitus”). The text for this piece shows the Greek philosopher Heraclitus in a perpetual fit of despondency:

My only pleasure is in weeping,

I feed on tears alone.

Dolor is my delight,

And my joy is sighing.

Strozzi presumably sang the cantata herself, impersonating a male in extremis. An ornate vocal line unfolds over a steady iteration of the Lamento della ninfa bass. It is an ambiguous, even androgynous scene, with gender identity melting away into a purely musical space of lamentation. For Strozzi, as for Dowland, melancholy may have been a site of self-creation, even giving hints of future freedom.

FRENCH AND ENGLISH CHACONNES

The chaconne had its apotheosis at Versailles. The music master at the court of Louis XIV was Jean-Baptiste Lully, who, like the chaconne itself, came from lowly circumstances; the son of a Florentine miller, he started out laboring as a servant and tutor to a princess who was a cousin of the king. When Lully exhibited performing talent, Louis hired him as a dancer, and shortly after set him to work composing. Lully created a series of grand ballets that he and Louis danced side by side; in later years, he became the chief opera composer of the kingdom, his clout confirmed by his friendship with the sovereign and his scandalous homosexual affairs largely excused. Productions at Versailles were so staggeringly lavish that many in the audience came principally to see the theatrical machinery. Plots were taken from mythology and chivalric tales, with unhappy endings modified to meet the harmonious ideals of the Sun King’s world.

Lully’s theater works routinely culminate in a majestic chaconne or passacaille. The flowing motion of these dances symbolizes the reconciliation of warring elements and the restoration of happiness. At the same time, an exotic association remains; a scholarly study by Rose Pruiksma notes that Lully’s chaconnes and passacailles are linked to Italian, Spanish, North African, even Chinese characters and locales. In Cadmus, a chaconne is performed by “thirteen Africans dancing and playing the guitar.” In Armide, a four-note passacaglia bass stands for the sorcery of the title character. And in the Ballet d’Alcidiane, from 1658, the union of the island princess and the hero Polexandre prompts a Chaconne des Maures, or Chaconne of the Moors. Louis himself performed as one of eight Moorish dancers, donning a black mask. The verses for the scene invoke the irresistible attraction of the darker-skinned males:

One dreads the arms of these lovely shadowed ones

And everything gives way to their charms,

Blondes, I say farewell to you.