Полная версия

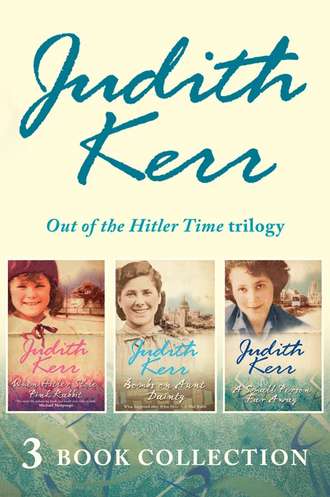

Out of the Hitler Time trilogy: When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, Bombs on Aunt Dainty, A Small Person Far Away

It was terribly hot but just bearable.

“That wasn’t so bad, was it?” said Mama.

Anna was much too angry to answer and the room was beginning to spin again, but as she drifted off into vagueness she could just hear Mama’s voice: “I’m going to get that temperature down if it kills me!”

After this she must have dozed or dreamed because suddenly her neck was quite cool again and Mama was unwrapping it.

“And how are you, fat pig?” said Mama.

“Fat pig?” said Anna weakly.

Mama very gently touched one of Anna’s swollen glands.

“This is fat pig,” she said. “It’s the worst of the lot. The one next to it isn’t quite so bad – it’s called slim pig. And this one is called pink pig and this is baby pig and this one …what shall we call this one?”

“Fräulein Lambeck,” said Anna and began to laugh. She was so weak that the laugh sounded more like a cackle but Mama seemed very pleased just the same.

Mama kept putting on the hot fomentations and it was not too bad because she always made jokes about fat pig and slim pig and Fräulein Lambeck, but though her neck felt better Anna’s temperature stayed up. She would wake up feeling fairly normal but by lunch time she would be giddy and by the evening everything would have become vague and confused. She got the strangest ideas. She was frightened of the wallpaper and could not bear to be alone. Once when Mama left her to go downstairs for supper she thought the room was getting smaller and smaller and cried because she thought she would be squashed. After this Mama had her supper on a tray in Anna’s room. The doctor said, “She can’t go on like this much longer.”

Then one afternoon Anna was lying staring at the curtains. Mama had just drawn them because it was getting dark and Anna was trying to see what shapes the folds had made. The previous evening they had made a shape like an ostrich, and as Anna’s temperature went up she had been able to see the ostrich more and more clearly until at last she had been able to make him walk all round the room. This time she thought perhaps there might be an elephant.

Suddenly she became aware of whispering at the other end of the room. She turned her head with difficulty. Papa was there, sitting with Mama, and they were looking at a letter together. She could not hear what Mama was saying, but she could tell from the sound of her voice that she was excited and upset. Then Papa folded the letter and put his hand on Mama’s, and Anna thought he would probably go soon but he didn’t – he just stayed sitting there and holding Mama’s hand. Anna watched them for a while until her eyes became tired and she closed them. The whispering voices had become more quiet and even. Somehow it was a very soothing sound and after a while Anna fell asleep listening to it.

When she woke up she knew at once that she had slept for a long time. There was something else, too, that was strange, but she could not quite make out what it was. The room was dim except for a light on the table by which Mama usually sat, and Anna thought she must have forgotten to switch it off when she went to bed. But Mama had not gone to bed. She was still sitting there with Papa just as they had done before Anna went to sleep. Papa was still holding Mama’s hand in one of his and the folded letter in the other.

“Hello, Mama. Hello, Papa,” said Anna. “I feel so peculiar.”

Mama and Papa came over to her bed at once and Mama put a hand on her forehead. Then she popped the thermometer in Anna’s mouth. When she took it out again she did not seem to be able to believe what she saw. “It’s normal!” she said. “For the first time in four weeks it’s normal!”

“Nothing else matters,” said Papa, and crumpled up the letter.

After this Anna got better quite quickly. Fat pig, slim pig, Fräulein Lambeck and the rest gradually shrank and her neck stopped hurting. She began to eat again and to read. Max came and played cards with her when he wasn’t out somewhere with Papa, and soon she was allowed to get out of bed for a little while and sit in a chair. Mama had to help her walk the few steps across the room but she felt very happy sitting in the warm sunshine by the window.

Outside the sky was blue and she saw that the people in the street below were not wearing overcoats. There was a lady selling tulips at a stall on the opposite pavement and a chestnut tree at the corner was in full leaf. It was spring. She was amazed how much everything had changed during her illness. The people in the street seemed pleased with the spring weather too and several bought flowers from the stall. The lady selling tulips was round and dark-haired and looked a little bit like Heimpi.

Suddenly Anna remembered something. Heimpi had been going to join them two weeks after they left Germany. Now it must be more than a month. Why hadn’t she come? She was going to ask Mama, but Max came in first.

“Max,” said Anna, “why hasn’t Heimpi come?”

Max looked taken aback. “Do you want to go back to bed?” he said.

“No,” said Anna.

“Well,” said Max, “I don’t know if I’m meant to tell you, but quite a lot happened while you were ill.”

“What?” asked Anna.

“You know Hitler won the elections,” said Max. “Well, he very quickly took over the whole government, and it’s just as Papa said it would be – nobody’s allowed to say a word against him. If they do they’re thrown into jail.”

“Did Heimpi say anything against Hitler?” asked Anna with a vision of Heimpi in a dungeon.

“No, of course not,” said Max. “But Papa did. He still does. And so of course no one in Germany is allowed to print anything he writes. So he can’t earn any money and we can’t afford to pay Heimpi any wages.”

“I see,” said Anna, and after a moment she added, “are we poor, then?”

“I think we are, a bit,” said Max. “Only Papa is going to try to write for some Swiss papers instead – then we’ll be all right again.” He got up as though to go and Anna said quickly, “I wouldn’t have thought Heimpi would mind about money. If we had a little house I think she’d want to come and look after us anyway, even if we couldn’t pay her much.”

“Yes, well, that’s another thing,” said Max. He hesitated before he added, “We can’t get a house because we haven’t any furniture.”

“But …” said Anna.

“The Nazis have pinched the lot,” said Max. “It’s called confiscation of property. Papa had a letter last week.” He grinned. “It’s been rather like one of those awful plays where people keep rushing in with bad news. And on top of it all there were you, just about to kick the bucket …”

“I wasn’t going to kick the bucket!” said Anna indignantly.

“Well, I knew you weren’t, of course,” said Max, “but that Swiss doctor has a very gloomy imagination. Do you want to go back to bed now?”

“I think I do,” said Anna. She was feeling rather weak and Max helped her across the room. When she was safely back in bed she said, “Max, this …confiscation of property, whatever it’s called – did the Nazis take everything – even our things?”

Max nodded.

Anna tried to imagine it. The piano was gone …the dining-room curtains with the flowers …her bed …all her toys which included her stuffed Pink Rabbit. For a moment she felt terribly sad about Pink Rabbit. It had had embroidered black eyes – the original glass ones had fallen out years before – and an endearing habit of collapsing on its paws. Its fur, though no longer very pink, had been soft and familiar. How could she ever have chosen to pack that characterless woolly dog in its stead? It had been a terrible mistake, and now she would never be able to put it right.

“I always knew we should have brought the games compendium,” said Max. “Hitler’s probably playing Snakes and Ladders with it this very minute.”

“And snuggling my Pink Rabbit!” said Anna and laughed. But some tears had come into her eyes and were running down her cheeks all at the same time.

“Oh well, we’re lucky to be here at all,” said Max.

“What do you mean?” asked Anna.

Max looked carefully past her out of the window.

“Papa heard from Heimpi,” he said with elaborate casualness. “The Nazis came for all our passports the morning after the elections.”

Chapter Six

As soon as Anna was strong enough they moved out of their expensive hotel. Papa and Max had found an inn in one of the villages on the lake. It was called Gasthof Zwirn, after Herr Zwirn who owned it, and stood very near the landing stage, with a cobbled courtyard and a garden running down to the lake. People mostly came there to eat and drink, but Herr Zwirn also had a few rooms to let, and these were very cheap. Mama and Papa shared one room and Anna and Max another, so that it would be cheaper still.

Downstairs there was a large comfortable dining room decorated with deers’ antlers and bits of edelweiss. But when the weather became warmer tables and chairs appeared in the garden, and Frau Zwirn served everybody’s meals under the chestnut trees overlooking the water. Anna thought it was lovely.

At weekends musicians came from the village and often played till late at night. You could listen to the music and watch the sparkle of the water through the leaves and the steamers gliding past. At dusk Herr Zwirn pressed a switch and little lights came on in the trees so that you could still see what you were eating. The steamers lit coloured lanterns to make themselves visible to other craft. Some were amber, but the prettiest were a deep, brilliant purply blue. Whenever Anna saw one of these magical blue lights against the darker blue sky and more dimly reflected in the dark lake, she felt as though she had been given a small present.

The Zwirns had three children who ran about barefoot and, as Anna’s legs began to feel less like cotton wool, she and Max went with them to explore the country round about. There were woods and streams and waterfalls, roads lined with apple trees and wild flowers everywhere. Sometimes Mama came with them rather than stay alone at the inn. Papa went to Zurich almost every day to talk to the editors of Swiss newspapers.

The Zwirn children, like everyone else living in the village, spoke a Swiss dialect which Anna and Max first found hard to understand. But they soon learned and the eldest, Franz, was able to teach Max to fish – only Max never caught anything – while his sister Vreneli showed Anna the local version of hopscotch.

In this pleasant atmosphere Anna soon recovered her strength and one day Mama announced that it was time for her and Max to start school again. Max would go to the Boys’ High School in Zurich. He would travel by train, which was not as nice as the steamer but much quicker. Anna would go to the village school with the Zwirn children, and as she and Vreneli were roughly the same age they would be in the same class.

“You will be my best friend,” said Vreneli. She had very long, very thin, mouse-coloured plaits and a worried expression. Anna was not absolutely sure that she wanted to be Vreneli’s best friend but thought it would be ungrateful to say so.

On Monday morning they set off together, Vreneli barefoot and carrying her shoes in her hand. As they approached the school they met other children, most of them also carrying their shoes. Vreneli introduced Anna to some of the girls, but the boys stayed on the other side of the road and stared across at them without speaking. Soon after they had reached the school playground a teacher rang a bell and there was a mad scramble by everyone to put their shoes on. It was a school rule that shoes must be worn but most children left them off till the last possible minute.

Anna’s teacher was called Herr Graupe. He was quite old with a greyish yellowish beard, and everyone was much in awe of him. He assigned Anna a place next to a cheerful fair-haired girl called Roesli, and as Anna walked down the centre aisle of the classroom to her desk there was a general gasp.

“What’s the matter?” Anna whispered as soon as Herr Graupe’s back was turned.

“You walked down the centre aisle,” Roesli whispered back. “Only the boys walk down the centre aisle.”

“Where do the girls go?”

“Round the sides.”

It seemed a strange arrangement, but Herr Graupe had begun to chalk up sums on the blackboard, so there was no time to go into it. The sums were very easy and Anna got them done quickly. Then she took a look round the classroom.

The boys were all sitting in two rows on one side, the girls on the other. It was quite different from the school she had gone to in Berlin where they had all been mixed up. When Herr Graupe called for the books to be handed in Vreneli got up to collect the girls’ while a big red-haired boy collected the boys’. The red-haired boy walked up the middle of the classroom while Vreneli walked round the side until they met, each with a pile of books, in front of Herr Graupe’s desk. Even there they were careful not to look at each other, but Anna noticed that Vreneli had turned a very faint shade of pink under her mouse-coloured hair.

At break-time the boys played football and horsed about on one side of the playground while the girls played hopscotch or sat sedately gossiping on the other. But though the girls pretended to take no notice of the boys they spent a lot of time watching them under their carefully lowered lids, and when Vreneli and Anna walked home for lunch Vreneli became so interested in the antics of the red-haired boy on the opposite side of the road that she nearly walked into a tree. They went back for an hour’s singing in the afternoon and then school was finished for the day.

“How do you like it?” Mama asked Anna when she got back at three o’clock.

“It’s very interesting,” said Anna. “But it’s funny – the boys and girls don’t even talk to each other and I don’t know if I’m going to learn very much.”

When Herr Graupe had corrected the sums he had made several mistakes and his spelling had not been too good either.

“Well, it doesn’t matter if you don’t,” said Mama. “It won’t hurt you to have a bit of a rest after your illness.”

“I like the singing,” said Anna. “They can all yodel and they’re going to teach me how to do it too.”

“God forbid!” said Mama and immediately dropped a stitch.

Mama was learning to knit. She had never done it before, but Anna needed a new sweater and Mama was trying to save money. She had bought some wool and some knitting needles and Frau Zwirn had shown her how to use them. But somehow Mama never looked quite right doing it. Where Frau Zwirn sat clicking the needles lightly with her fingers, Mama knitted straight from the shoulder. Each time she pushed the needle into the wool it was like an attack. Each time she brought it out she pulled the stitch so tight that it almost broke. As a result the sweater only grew slowly and looked more like heavy tweed than knitting.

“I’ve never seen work quite like it,” said Frau Zwirn, astonished, when she saw it, “but it’ll be lovely and warm when it’s done.”

One Sunday morning soon after Anna and Max had started school they saw a familiar figure get off the steamer and walk up the landing stage. It was Onkel Julius. He looked thinner than Anna remembered and it was wonderful and yet somehow confusing to see him – as though a bit of their house in Berlin had suddenly appeared by the edge of the lake.

“Julius!” cried Papa in delight when he saw him. “What on earth are you doing here?”

Onkel Julius gave a little wry smile and said, “Well, officially I’m not here at all. Do you know that nowadays it is considered very unwise even to visit you?” He had been to a naturalists’ congress in Italy and had left a day early in order to come and see them on his way back to Berlin.

“I’m honoured and grateful,” said Papa.

“The Nazis certainly are very stupid,” said Onkel Julius. “How could you possibly be an enemy of Germany? You know of course that they burned all your books.”

“I was in very good company,” said Papa.

“What books?” asked Anna. “I thought the Nazis had just taken all our things – I didn’t know they’d burned them.”

“These were not the books your father owned,” said Onkel Julius. “They were the books he has written. The Nazis lit big bonfires all over the country and threw on all the copies they could find and burned them.”

“Along with the works of various other distinguished authors,” said Papa, “such as Einstein, Freud, H. G. Wells …”

Onkel Julius shook his head at the madness of it all.

“Thank heavens you didn’t take my advice,” he said. “Thank heavens you left when you did. But of course,” he added, “this situation in Germany can’t go on much longer!”

Over lunch in the garden he told them the news. Heimpi had found a job with another family. It had been difficult because when people heard that she had worked for Papa they did not want to employ her. But it was not a bad job considering. Their house was still empty. Nobody had bought it yet.

It was strange, thought Anna, that Onkel Julius could go and look at it any time he liked. He could walk down the street from the paper shop at the corner and stand outside the white painted gate. The shutters would be closed but if he had a key Onkel Julius would be able to go through the front door into the dark hall, up the stairs to the nursery, or across into the drawing room, or along the passage to Heimpi’s pantry …Anna remembered it all so clearly, and in her mind she walked right through the house from top to bottom while Onkel Julius went on talking to Mama and Papa.

“How are things with you?” he asked. “Are you able to write here?”

Papa raised an eyebrow. “I have no difficulty in writing,” he said, “only in getting my work published.”

“Impossible!” said Onkel Julius.

“Unfortunately not,” said Papa. “It seems the Swiss are so anxious to protect their neutrality that they are frightened of publishing anything by an avowed anti-Nazi like myself.”

Onkel Julius looked shocked.

“Are you all right?” he asked. “I mean – financially?”

“We manage,” said Papa. “Anyway, I’m trying to make them change their mind.”

Then they began to talk about mutual friends. It sounded as though they were going through a long list of names. Somebody had been arrested by the Nazis. Somebody else had escaped and was going to America. Another person had compromised (what was “compromised”? wondered Anna) and had written an article in praise of the new regime. The list went on and on. All grown-up conversations were like this nowadays, thought Anna, while little waves lapped against the edge of the lake and bees buzzed in the chestnut trees.

In the afternoon they showed Onkel Julius round. Anna and Max took him up into the woods and he was very interested to discover a special kind of toad that he had never seen before. Later, they all went for a row on the lake in a hired boat. Then they had supper together, and at last it was time for Onkel Julius to leave.

“I miss our outings to the Zoo,” he said as he kissed Anna.

“So do I!” said Anna. “I liked the monkeys best.”

“I’ll send you a picture of one,” said Onkel Julius.

They walked down to the landing stage together.

While they were waiting for the steamer Papa suddenly said, “Julius – don’t go back. Stay here with us. You won’t be safe in Germany.”

“What – me?” said Onkel Julius in his high voice. “Who’s going to bother about me? I’m only interested in animals. I’m not political. I’m not even Jewish unless you count my poor old grandmother!”

“Julius, you don’t understand …” said Papa.

“The situation is bound to change,” said Onkel Julius, and there was the steamer puffing towards them. “Goodbye, old friend!” He embraced Papa and Mama and both children.

As he walked across the gangplank he turned back for a moment.

“Anyway,” he said, “the monkeys at the Zoo would miss me!”

Chapter Seven

As Anna went on attending the village school she liked it more and more. She made friends with other girls apart from Vreneli, and especially with Roesli, who sat next to her in class and was a little less sedate than the rest. The lessons were so easy that she was able to shine without any effort, and though Herr Graupe was not a very good teacher of the more conventional subjects he was a remarkable yodeller. Altogether what she liked best about the school was that it was so different from the one she had been to before. She felt sorry for Max who seemed to be doing very much the same things at the Zurich High School as he had done in Berlin.

There was only one thing that bothered her. She missed playing with boys. In Berlin she and Max had mostly played with a mixed group of both boys and girls and it had been the same at school. Here the girls’ endless hopscotch began to bore her and sometimes in break she looked longingly at the more exciting games and acrobatics of the boys.

One day there was no one even playing hopscotch. The boys were turning cartwheels and all the girls were sitting demurely watching them out of the corner of their eyes. Even Roesli, who had cut her knee, was sitting with the rest. Vreneli was particularly interested because the big red-haired boy was trying to turn cartwheels and the others were trying to teach him, but he kept flopping over sideways.

“Would you like to play hopscotch?” Anna asked her, but Vreneli shook her head, absorbed. It really was too silly, especially as Anna loved turning cartwheels herself – and it wasn’t as though the red-haired boy was any good at it.

Suddenly she could stand it no longer and without thinking what she was doing she got up from her seat among the girls and walked over to the boys.

“Look,” she said to the red-haired boy, “you’ve got to keep your legs straight like this” – and she turned a cartwheel to show him. All the other boys stopped turning cartwheels and stood back, grinning. The red-haired boy hesitated.

“It’s quite easy,” said Anna. “You could do it if you’d only remember about your legs.”

The red-haired boy still seemed undecided, but the other boys shouted, “Go on – try!” So he tried again and managed a little better. Anna showed him again, and this time he suddenly got the idea and turned a perfect cartwheel just as the bell went for the end of break.

Anna walked back to her own group and all the boys watched and grinned but the girls seemed mostly to be looking elsewhere. Vreneli looked frankly cross and only Roesli gave her a quick smile.

After break it was history and Herr Graupe decided to tell them about the cavemen. They had lived millions of years ago, he said. They killed wild animals and ate them and made their fur into clothes. Then they learned to light fires and make simple tools and gradually became civilized. This was progress, said Herr Graupe, and one way it was brought about was by pedlars who called at the cavemen’s caves with useful objects for barter.

“What sort of useful objects?” asked one of the boys.

Herr Graupe peered indignantly over his beard. All sorts of things would be useful to a caveman, he said. Things like beads, and coloured wools, and safety pins to fasten their furs together. Anna was very surprised to hear about the pedlars and the safety pins. She longed to ask Herr Graupe whether he was really sure about them but thought perhaps it would be wiser not to. Anyway the bell went before she had the chance.

She was still thinking about the cavemen so much on the way home to lunch that she and Vreneli had walked nearly halfway before she realized that Vreneli was not speaking to her.

“What’s the matter, Vreneli?” she asked.

Vreneli tossed her thin plaits and said nothing.

“What is it?” asked Anna again.

Vreneli would not look at her.