Полная версия

Out of the Hitler Time trilogy: When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, Bombs on Aunt Dainty, A Small Person Far Away

“Do you like your school?” Max suddenly asked as they were walking back.

“Yes,” said Anna. “Everybody is very nice, and they don’t mind if I can’t understand what they say. Why? Don’t you like yours?”

“Oh yes,” said Max. “They’re nice to me too, and I’m even beginning to understand French.”

They walked in silence a little way and then suddenly burst out with, “But there’s one thing I absolutely hate!”

“What?” asked Anna.

“Well – doesn’t it bother you?” said Max. “I mean – being so different from everyone else?”

“No,” said Anna. Then she looked at Max. He was wearing a pair of outgrown shorts and had turned them up to make them even shorter. There was a scarf dashingly tucked into the collar of his jacket and his hair was brushed in an unfamiliar way.

“You look exactly like a French boy,” said Anna.

Max brightened for a moment. Then he said, “But I can’t speak like one.”

“Well, of course you can’t, after such a short time,” said Anna. “I suppose sooner or later we’ll both learn to speak French properly.”

Max stumped along grimly.

Then he said, “Well, in my case it’s definitely going to be sooner rather than later!”

He looked so fierce that even Anna who knew him well was surprised at the determination in his face.

Chapter Sixteen

One Thursday afternoon a few weeks after Anna had started school she and Mama went to visit Great-Aunt Sarah. Great-Aunt Sarah was Omama’s sister but had married a Frenchman, now deceased, and had lived in Paris for thirty years. Mama, who had not seen her since she was a little girl, put on her best clothes for the occasion. She looked very young and pretty in her good coat and her blue hat with the veil, and as they walked towards the Avenue Foch where Great-Aunt Sarah lived, several people turned round to look at her.

Anna had put on her best clothes too. She was wearing the sweater Mama had knitted, her new shoes and socks, and Onkel Julius’s bracelet, but her skirt and coat were horribly short. Mama sighed, as always, at the sight of Anna in her outdoor things.

“I’ll have to ask Madame Fernand to do something with your coat,” she said. “If you grow any more it won’t even cover your pants.”

“What could Madame Fernand do?” asked Anna.

“I don’t know – stitch a bit of material round the hem or something,” said Mama. “I wish I knew how to do these things, like her!”

Mama and Papa had been to dinner with the Fernands the previous week and Mama had come back bursting with admiration. In addition to being a wonderful cook Madame Fernand made all her own and her daughter’s clothes. She had re-upholstered a sofa and made her husband a beautiful dressing-gown. She had even made him some pyjamas when he could not find the colour he wanted in the shops.

“And she does it all so easily,” said Mama, for whom sewing on a button was a major undertaking – “as though it weren’t work at all.”

Madame Fernand had offered to help with Anna’s clothes, too, but Mama had felt perhaps that would be too much to accept. Now, however, seeing Anna stick out of her coat in all directions, she changed her mind.

“I will ask her,” she said. “If she just showed me how to do it perhaps I could manage it myself.”

By this time they had arrived at their destination. Great-Aunt Sarah lived in a large house set back from the road. They had to cross a courtyard planted with trees to reach it and the concierge who directed them to her flat wore a uniform with gold buttons and braid. Great-Aunt Sarah’s lift was made of plate glass and carried them swiftly upwards without any of the groans and shudders Anna was used to, and her front door was opened by a maid in a frilly white apron and cap.

“I’ll tell Madame you’re here,” said the maid, and Mama sat on a little velvet chair while the maid went into what must be the drawing room. As she opened the door they could hear a buzz of voices and Mama looked worried and said, “I hope this is the right day …” But almost at once the door opened again and Great-Aunt Sarah ran out. She was a stout old lady but she moved at a brisk trot and for a moment Anna wondered whether she would be able to stop when she reached them.

“Nu,” she cried, throwing her heavy arms round Mama. “So here you are at last! Such a long time I haven’t seen you – and such dreadful things happening in Germany. Still, you’re safe and well and that’s all that matters.” She relapsed into another velvet chair, overflowing on all sides, and said to Anna, “Do you know that the last time I saw your Mama she was only a little girl? And now she has a little girl of her own. What’s your name?”

“Anna,” said Anna.

“Hannah – how nice. A good Jewish name,” said Great-Aunt Sarah.

“No, Anna,” said Anna.

“Oh, Anna. That’s a nice name too. You must excuse me,” said Great-Aunt Sarah, leaning perilously towards her on the little chair, “but I’m a bit deaf.” Her eyes took in Anna properly for the first time and she looked astonished. “Goodness, child,” she exclaimed. “Such long legs you have! Aren’t they cold?”

“No,” said Anna. “But Mama says if I grow any more my coat won’t even cover my pants.”

As soon as the words were out of her mouth, she wished she had not said them. It was not the sort of thing one said to a great-aunt one hardly knew.

“What?” said Great-Aunt Sarah.

Anna could feel herself blushing.

“A moment,” said Great-Aunt Sarah and suddenly from somewhere about her person, she produced an object like a trumpet. “There,” she said, putting the thin end not to her mouth as Anna had half-expected, but to her ear. “Now say it again, child – very loudly – into my trumpet.”

Anna tried desperately to think of something quite different that she could say instead and that would still make sense, but her mind remained blank. There was nothing for it.

“Mama says,” she shouted into the ear-trumpet, “that if I grow any more my coat won’t even cover my pants!”

When she withdrew her face she could feel that she had gone scarlet.

Great-Aunt Sarah seemed taken aback for a moment. Then her face crumpled up and a noise somewhere between a wheeze and a chuckle escaped from it.

“Quite right!” she cried, her black eyes dancing. “Your mama is quite right! But what is she going to do about it, eh?” Then she added to Mama, “Such a funny child – such a nice funny child you have!” And rising from the chair with surprising agility she said, “So now you must come and have some tea. There are some old ladies here who have been playing bridge, but I’ll soon get rid of them” – and she led the way, at a gentle gallop, into the drawing room.

The first thing that struck Anna about Great-Aunt Sarah’s old ladies was that they all looked a good deal younger than Great-Aunt Sarah. There were about a dozen of them, all elegantly dressed with elaborate hats. They had finished playing bridge – Anna could see the card tables pushed back against the wall – and were now drinking tea and helping themselves to tiny biscuits which the maid was handing round on a silver tray.

“Every Thursday they come,” whispered Great-Aunt Sarah in German. “Poor old things, they have nothing better to do. But they’re all very rich and they give me money for my needy children.”

Anna, who had only just got over her surprise at Great-Aunt Sarah’s old ladies, found it even more difficult to imagine her with needy children – or indeed with any children at all – but she did not have time to ponder the problem for she was being loudly introduced along with Mama.

“My niece and her daughter have come from Germany,” shouted Great-Aunt Sarah in French but with a strong German accent. “Say bongshour!” she whispered to Anna.

“Bonjour,” said Anna.

Great-Aunt Sarah threw up her hands in admiration. “Listen to the child!” she cried. “Only a few weeks she has been in Paris and already she speaks French better than I!”

Anna found it difficult to keep up this impression when one of the ladies tried to engage her in conversation, but she was saved from further efforts when Great-Aunt Sarah’s voice boomed out again.

“I have not seen my niece for years,” she shouted, “and I have been longing to have a talk with her.”

At this the ladies hurriedly drank up their tea and began to make their farewells. As they shook hands with Great-Aunt Sarah they dropped some money into a box which she held out to them, and she thanked them. Anna wondered just how many needy children Great-Aunt Sarah had got. Then the maid escorted the ladies to the door and at last they had all disappeared.

It was nice and quiet without them, but Anna noticed with regret that the silver tray with the little biscuits had disappeared along with the ladies and that the maid was gathering up the empty cups and carrying them out of the room. Great-Aunt Sarah must have forgotten her promise of tea. She was sitting on the sofa with Mama and telling her about her needy children. It turned out that they were not her own after all but a charity for which she was collecting money, and Anna who had briefly pictured Great-Aunt Sarah with a secret string of ragged urchins felt somehow cheated. She wriggled restlessly in her chair, and Great-Aunt Sarah must have noticed for she suddenly interrupted herself.

“The child is bored and hungry,” she cried and added to the maid, “Have the old ladies all gone?”

The maid replied that they had.

“Well then,” cried Great-Aunt Sarah, “you can bring in the real tea!”

A moment later the maid staggered back under a tray loaded with cakes. There must have been five or six different kinds, apart from an assortment of sandwiches and biscuits. There was also a fresh pot of tea, chocolate and whipped cream.

“I like cakes,” said Great-Aunt Sarah in answer to Mama’s look of astonishment, “but it’s no use offering them to those old ladies – they’re much too careful of their diets. So I thought we’d have our tea after they’d gone.” So saying she slapped a large portion of apple flan on to a plate, topped it with whipped cream and handed it to Anna. “The child needs feeding,” she said.

During tea she asked Mama questions about Papa’s work and about their flat, and sometimes Mama had to repeat her answers into the ear-trumpet. Mama talked about everything quite cheerfully, but Great-Aunt Sarah kept shaking her head and saying, “To have to live like this …such a distinguished man …!” She knew all Papa’s books and bought the Daily Parisian specially to read his articles. Every so often she would look at Anna, saying, “And the child – so skinny!” and ply her with more cake.

At last, when no one could eat any more, Great-Aunt Sarah heaved herself out from behind the tea-table and set off at her usual trot towards the door, beckoning to Mama and Anna to follow. She led them to another room which seemed to be entirely filled with cardboard boxes.

“Look,” she said. “All this I have been given for my needy children.”

The boxes were filled with lengths of cloth in all sorts of different colours and thicknesses.

“One of my old ladies is married to a textile manufacturer,” explained Great-Aunt Sarah. “So he is very rich and he gives me all the ends of material he does not want. Now I have an idea – why shouldn’t the child have some of it? After all it is for needy children, and she is as needy as most.”

“No, no,” said Mama, “I don’t think I could …”

“Ach – always so proud,” said Great-Aunt Sarah. “The child needs new clothes. Why shouldn’t she have some?”

She rummaged in one of the boxes and pulled out some thick woollen material in a lovely shade of green. “Just nice for a coat,” she said, “and a dress she needs, and perhaps a skirt …”

In no time at all she had assembled a pile of cloth on the bed, and when Mama tried again to refuse she only cried, “Such nonsense! You want the police should arrest the child for going about with her pants showing?”

At this Mama who had in any case not been protesting very hard, had to laugh and give in. The maid was asked to wrap it all up, and when it was time to leave Mama and Anna each had a big parcel to carry.

“Thank you very, very much!” Anna shouted into Great-Aunt Sarah’s ear-trumpet. “I’ve always wanted a green coat!”

“I wish you luck to wear it!” Great-Aunt Sarah shouted back.

Then they were outside, and as Anna and Mama walked back in the dark they talked all the way about the different pieces of material and what they could be made into. As soon as they got home Mama telephoned Madame Fernand who was delighted and said they must bring everything round the following Thursday for a great dress-making session.

“Won’t it be lovely!” cried Anna. “I can’t wait to tell Papa!” – and just then Papa came in. She told him excitedly what had happened. “And I’ll be able to have a dress and a coat,” she gabbled, “and Great-Aunt Sarah just gave it to us because it was meant for needy children and she said I was as needy as most, and we had a lovely tea and …”

She stopped because of the expression on Papa’s face.

“What is all this?” he said to Mama.

“It’s just as Anna told you,” said Mama, and there was something careful about her voice. “Great-Aunt Sarah had a whole lot of cloth which had been given to her and she wanted Anna to have some.”

“But it had been given to her for needy children,” said Papa.

“That’s only what it was called,” said Mama. “She’s interested in various charities – she’s a very kind woman …”

“Charities?” asked Papa. “But we can’t accept charity for our children.”

“Oh, why must you always be so difficult?” shouted Mama. “The woman is my aunt and she wanted Anna to have some clothes – that’s all there is to it!”

“Honestly, Papa, I don’t think she meant it in any way you wouldn’t like,” Anna put in. She was feeling miserable and almost wished she had never seen the cloth.

“It’s a present for Anna from a relative,” said Mama.

“No,” said Papa. “It’s a present from a relative who runs a charity – a charity for needy children.”

“All right then, we’ll give it back!” shouted Mama. “If that’s what you want! But will you tell me what the child is going to wear? Do you know the price of children’s clothes in the shops? Look at her – just look at her!”

Papa looked at Anna and Anna looked back at him. She wanted the new clothes but she did not want Papa to feel so badly about them. She tugged at her skirt to make it look longer.

“Papa …” she said.

“You do look a bit needy,” said Papa. His face looked very tired.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Anna.

“Yes, it does,” said Papa. “It does matter.” He fingered the stuff in the parcels. “Is this the cloth?”

She nodded.

“Well then, you’d better get it made up into some new clothes,” said Papa. “Something warm,” he said and went out of the room.

In bed that night Anna and Max lay talking in the dark.

“I didn’t know we were needy,” said Anna. “Why are we?”

“Papa doesn’t earn a lot,” said Max. “The Daily Parisian can’t afford to pay him very much for his articles and the French have their own writers.”

“They used to pay him a lot in Germany.”

“Oh yes.”

For a while they lay without talking. Then Anna said, “Funny, isn’t it?”

“What?”

“How we used to think we’d be back in Berlin within six months. We’ve been away more than a year already.”

“I know,” said Max.

Suddenly, for no particular reason, Anna remembered their old house so vividly that she could almost see it. She remembered what it felt like to run up the stairs and the little patch on the carpet on the landing where she had once spilt some ink, and how you could see the pear tree in the garden from the windows. The nursery curtains were blue and there was a white-painted table to write or draw on and Bertha the maid had cleaned it all every day and there had been a lot of toys …But it was no use going on thinking about it, so she closed her eyes and went to sleep.

Chapter Seventeen

The dressmaking session at the Fernands was a great success. Madame Fernand was just as nice as Anna remembered her, and she cut out Great-Aunt Sarah’s cloth so cleverly that there was enough for a pair of grey shorts for Max as well as a coat, a dress and a skirt for Anna. When Mama offered to help with the sewing Madame Fernand looked at her and laughed.

“You go and play the piano,” she said, “I’ll get on with this.”

“But I’ve even brought some sewing things,” said Mama. She dug in her handbag and produced an elderly reel of white cotton and a needle.

“My dear,” said Madame Fernand quite kindly, “I wouldn’t trust you to hem a handkerchief.”

So Mama played the piano at one end of the Fernands’ pleasant sitting room while Madame Fernand sewed at the other, and Anna and Max went off to play with the Fernand’s daughter Francine.

Max had had grave doubts about Francine before they came.

“I don’t want to play with a girl!” he had said, and even claimed that he could not come because of his homework.

“You’ve never been so keen on your homework before!” said Mama crossly, but it was not really fair because lately, in his efforts to learn French as fast as possible, Max had become much more conscientious about school. He was deeply offended and scowled at everyone until they arrived at the Fernands’ flat and Francine opened the door for them. Then his scowl quickly disappeared. She was a remarkably pretty girl with long honey-coloured hair and large grey eyes.

“You must be Francine,” said Max and added untruthfully but in surprisingly good French, “I have so much looked forward to meeting you!”

Francine had quite a lot of toys and a big white cat. The cat immediately took possession of Anna and sat on her lap while Francine searched for something in her toy cupboard. At last she found it.

“This is what I got for my birthday,” she said and produced a games compendium very like the one Anna and Max had owned in Germany.

Max’s eyes met Anna’s over the cat’s white fur.

“Can I see?” he asked and had it open almost before Francine agreed. He took a long time looking at the contents fingering the dice, the chessmen, the different kinds of playing cards.

“We used to have a box of games like this,” he said at last. “Only ours had dominoes as well.”

Francine looked a little put out at having her birthday present belittled.

“What happened to yours?” she asked.

“We had to leave it behind,” said Max and added gloomily, “I expect Hitler plays with it now.”

Francine laughed. “Well, you’ll have to use this one instead,” she said. “As I have no brothers or sisters I don’t often have anyone to play with.”

After this they played Ludo and Snakes and Ladders all afternoon. It was nice because the white cat sat on Anna’s lap and there was no need for her to speak much French during the games. The white cat seemed quite happy to have dice thrown over its head and did not want to get down even when Madame Fernand called Anna to try on the new clothes. For tea it ate a bit of iced bun which Anna gave it, and afterwards it climbed straight back on to her lap and smiled at her through its long white fur. When it was time to leave it followed her to the front door.

“What a pretty cat,” said Mama when she saw it.

Anna was longing to tell her how it had sat on her lap while she had played Ludo but thought it would be rude to speak German when Madame Fernand could not understand it. So, very haltingly, she explained in French.

“I thought you told me Anna spoke hardly any French,” said Madame Fernand.

Mama looked very pleased. “She is beginning to,” she said.

“Beginning to!” exclaimed Madame Fernand. “I’ve never seen two children learn a language so fast. Max sounds almost like a French boy at times and as for Anna – only a month or two ago she could hardly say a word, and now she understands everything!”

It was not quite true. There were still a lot of things Anna could not understand – but she was delighted just the same. She had been so impressed with Max’s rapid progress that she had not noticed how much she herself had improved.

Madame Fernand wanted them all to come again the following Sunday so that Anna could have a final fitting, but Mama said, no, next time all the Fernands must come to them – and thus began a series of visits which both families found so pleasant that it soon became a regular arrangement.

Papa especially enjoyed Monsieur Fernand’s company. He was a large clever-looking man and often, while the children played in the dining room at home, Anna could hear his deep voice and Papa’s in the bedroom-turned-sitting-room next door. They seemed to have endless things to talk about and sometimes Anna could hear them laughing loudly together. This always pleased her because she had hated the tired look on Papa’s face when he had heard about Great-Aunt Sarah’s cloth. She had noticed since that this look occasionally returned – usually when Mama was talking about money. Monsieur Fernand was always able to keep the look at bay.

The new clothes were soon finished and turned out to be the nicest Anna had ever had. She went to show them to Great-Aunt Sarah the very first time she wore them and took with her a poem she had composed specially as a thanks offering. It described all the clothes in detail and ended with the lines.

“And so I am the happy wearer

Of all these nice clothes from Aunt Sarah.”

“Goodness, child,” said Great-Aunt Sarah when she read it. “You’ll be such a writer yet, like your father!”

She seemed terribly pleased with it.

Anna was pleased too because somehow the poem seemed to make it quite definite that the gift of cloth had not been charity – and also it was the first time she had ever managed to write a poem about anything other than a disaster.

Chapter Eighteen

In April it suddenly became spring, and though Anna tried to go on wearing the beautiful green coat which Madame Fernand had made for her she soon found it much too thick.

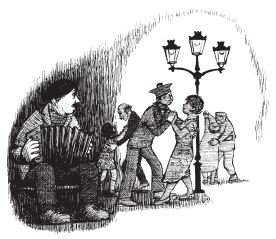

Walking to school became a delight on these bright, sunny mornings, and as the Parisians opened their windows to let in the warm air all sorts of interesting smells escaped and mingled with the scent of spring in the streets. Apart from the usual hot garlicky breath rising from the Metro she suddenly encountered delicious waftings of coffee, freshly baked bread, or onions being fried ready for lunch. As the spring advanced, doors were opened as well as windows, and while walking down the sunlit streets she could glimpse the dim interiors of cafés and shops which had been invisible all through the winter. Everyone wanted to linger in the sunshine, and the pavements in the Champs Elysées became a sea of tables and chairs amongst which white-coated waiters flew about, serving drinks to their customers.

The first of May was called the day of the lily-of-the-valley. Baskets piled high with the little green and white bunches appeared at every street corner and the cries of the vendors echoed everywhere. Papa had an early appointment that morning and walked part of the way to school with Anna. He stopped to buy a paper from an old man at a kiosk. There was a picture of Hitler on the front page, making a speech, but the old man folded the paper in half so that Hitler disappeared. Then he sniffed the air appreciatively and smiled, showing one tooth.

“It smells of spring!” he said.

Papa smiled back and Anna knew that he was thinking how lovely it was to be spending this spring in Paris. At the next corner they bought some lily-of-the-valley for Mama without even asking first how much they cost.