Полная версия

Paddington Here and Now

Copyright

First published in hardback in Great Britain by

HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2008

This edition published in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF.

www.harpercollinschildrensbooks.co.uk

Text copyright © Michael Bond 2008

Illustrations copyright © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2008

Cover illustration copyright © Peggy Fortnum and HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2008

The author asserts the moral right to be identified

as the author of the work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins eBooks.

Conditions of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition

that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise,

be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated

without the publisher’s prior consent in any

form, binding or cover other than that in which

it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on

the subsequent purchaser.

Source ISBN: 9780007269419

eBook Edition June 2008 ISBN: 9780007281916

Version: 2018-05-23

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

1. Parking Problems

2. Paddington’s Good Turn

3. Paddington Strikes a Chord

4. Paddington Takes the Biscuit

5. Paddington Spills the Beans

6. Paddington Aims High

7. Paddington’s Christmas Surprise

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Chapter One

PARKING PROBLEMS

“MY SHOPPING BASKET on wheels has been towed away!” exclaimed Paddington hotly.

He gazed at the spot where he had left it before going into the cut-price grocers in the Portobello Market. In all the years he had lived in London such a thing had never happened to him before and he could hardly believe his eyes. But if he thought staring at the empty space was going to make it reappear he was doomed to disappointment.

“It’s coming to something if a young bear gent can’t leave ’is shopping basket unattended for five minutes while ’e’s going about ’is business,” said one of the stallholders, who normally supplied Paddington with vegetables when he was out shopping for the Brown family. “I don’t know what the world’s coming to.”

“There’s no give and take any more,” agreed a man at the next stall. “It’s all take and no give. They’ll be towing us away next, you mark my words.”

“You should have left a note on it saying ‘Back in five minutes’,” said a third one.

“Fat lot of good that would have done,” said another. “They don’t give you five seconds these days, let alone five minutes.”

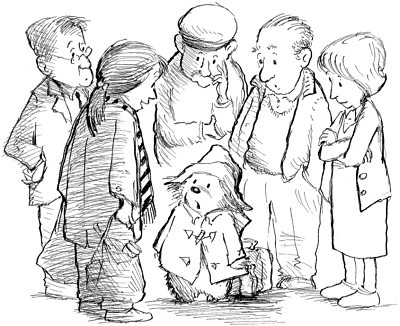

Paddington was a popular figure in the market and by now a small crowd of sympathisers had begun to gather. Although he was known to drive a hard bargain, he was much respected by the traders. Receiving his custom was regarded by many as being something of an honour: on a par with having a sign saying they were by appointment to a member of the Royal Family.

“The foreman of the truck said it was in the way of his vehicle,” said a lady who had witnessed the event. “They were trying to get behind a car they wanted to tow away.”

“But my buns were in it,” said Paddington.

“Were, is probably the right word,” replied the lady. “I dare say even now they’re parked in some side street or other wolfing them down. Driving those great big tow-away trucks of theirs must give them an appetite.”

“I don’t know what Mr Gruber is going to say when he hears,” said Paddington. “They were meant for our elevenses.”

“Look on the bright side,” said another lady. “At least you’ve still got your suitcase with you. The basket could have been clamped. That would have cost you £80 to get it undone.”

“And you would have to hang about half the day before they got around to doing it,” agreed another.

Paddington’s face grew longer and longer as he listened to all the words of wisdom. “Eighty pounds!” he exclaimed. “But I only went in for Mrs Bird’s bottled water!”

“You can buy a new basket on wheels in the market for £10,” chimed in another stallholder.

“I dare say if you haggle a bit you could get one for a lot less,” said another.

“But I’ve only got ten pence,” said Paddington sadly. “Besides, I wouldn’t want a new one. Mr Brown gave mine to me soon after I arrived. I’ve had it ever since.”

“Quite right!” agreed an onlooker. “You stick to your guns. They don’t come like that these days. Them new ones is all plastic. Don’t last five minutes.”

“If you ask me,” said a lady who ran a knickknacks stall, “it’s a pity it didn’t get clamped. My Sid would have lent you his hacksaw like a shot. He doesn’t hold with that kind of thing.”

“Pity you weren’t here in person when they did it,” said another stallholder. “You would have been able to lie down in the road in front of their truck as a protest. Then we could have phoned the local press to send over one of their photographers and it would have been in all the papers.”

“That would have stopped the lorry in its tracks,” agreed someone else from the back of the crowd.

Paddington eyed the man doubtfully. “Supposing it didn’t?” he said.

“In that case you would have been on the evening news,” said the man. “Television would have had a field day interviewing all the witnesses.”

“You’d have become what they call a martyr,” agreed the first man. “I dare say in years to come they would have erected a statue in your honour. Then nobody would have been able to park.”

“What you need,” said the fruit and vegetable man, summing up the whole situation, “is a good lawyer. Someone like Sir Bernard Crumble. He lives just up the road. This kind of thing is just up his street. He’s a great one for sticking up for the underdog…” he broke off as he caught Paddington’s eye. “Well, I dare say he does underbears as well. He’d have their guts for garters. Never been known to lose a case yet.”

“Which street does he live in?” asked Paddington hopefully.

“I shouldn’t get ideas above your station,” warned another trader. “If you’ll pardon the pun. They do say ’e charges an arm and a leg just to open ’is front door to the postman.”

“If I were you,” said a passer-by, “before you do anything else, I suggest you go along to the police station and report the matter to them. I dare say they’ll be able to arrange counselling for you.”

“Whatever you do,” advised one of the stallholders, “don’t tell them you’ve been towed away. Be what they call non committal. Just say your vehicle has gone missing.”

He gazed at the large pack of bottled water Paddington had bought in the grocers. “You can leave those with me. I’ll make sure they don’t come to any harm.”

Paddington thanked the man for his kind offer and after waving goodbye to the crowd he set off at a brisk pace towards the nearest police station.

But as he turned a corner and a familiar blue lamp came into view, he began to slow down. Over the years he had met a number of policemen and he had always found them only too ready to help in times of trouble. There was the occasion when he’d mistaken a television repairman for a burglar, and another time when he had bought some oil shares from a man in the market and they had turned out to be dud.

But he had never actually gone into a police station all by himself before, and not knowing what to expect he began to wish he had consulted his friend, Mr Gruber, before taking the plunge. Mr Gruber was always ready to help, and he most certainly would have done so had he heard their buns were missing. He might even have closed his shop for the morning.

And if he couldn’t do that for any reason, there was always Mrs Bird. Mrs Bird looked after the Browns, and she didn’t stand for any nonsense, especially if she thought Paddington was being hard done by.

However, as things turned out, he was pleasantly surprised when he mounted the steps and pushed the door slightly ajar. Apart from a man in uniform behind a counter, the room was completely empty.

The man was much younger than he had expected. In fact, he didn’t seem much older than Mr and Mrs Brown’s son, Jonathan, who was still at school. He looked slightly apprehensive when he caught sight of Paddington, rather as though he didn’t know quite what to make of him.

“Er… Sprechen Sie Deutsch?” he ventured nervously.

“Bless you,” said Paddington, politely raising his hat. “You can borrow my handkerchief if you like.”

The policeman gave him a funny look before trying again.

“Parlez-vous français?”

“Not today, thank you,” said Paddington.

“Pardon me for asking,” said the officer. “But it’s ‘Be Polite to Foreigners Week’. Strictly unofficial, of course. It’s the Sergeant’s idea because we get a lot of overseas visitors at this time of the year, especially round the Portobello Road area, and I thought perhaps…”

“I’m not a foreigner,” exclaimed Paddington hotly. “I’m from Darkest Peru.”

The policeman looked put out. “Well, if that doesn’t make you a foreigner, I don’t know what does,” he said. “Mind you, it takes all sorts. I must say you speak very good English, wherever you’re from.”

“My Aunt Lucy taught me before she went into the Home for Retired Bears in Lima,” said Paddington.

“Well, she did a good job, I’ll say that for her,” said the policeman. “What can we do for you?”

“I’ve come to see you about my vehicle,” said Paddington, choosing his words with care. “It isn’t where I left it.”

“And where was that?” asked the policeman.

“Outside the cut-price grocers in the market,” said Paddington. “I always leave it there when I’m out shopping.”

“Oh, dear,” said the officer. “Not another one gone missing. There’s a lot of it about at the moment, especially round these parts…” He reached for a computer keyboard. “I’d better take down some details.”

“It had my buns in it,” said Paddington.

“That’s not a lot to go on,” said the policeman. “I was wondering what make it is?”

“It’s not really a make,” said Paddington vaguely. “Mr Brown built it for me when I first went to stay with them.”

“Home-made,” said the officer, typing in the words. “Ahhhhh! Colour?”

“I think it’s called wickerwork,” said Paddington.

“I’ll put down yellow for the time being,” said the man. “Did you leave the handbrake on? That always slows them down a bit when they want to make a quick getaway.”

“It doesn’t have a handbrake,” said Paddington. “It doesn’t even have a paw brake. If I need to stop on a hill I usually put some stones under the wheels. Especially if I’ve been to get the potatoes.”

“Potatoes?” echoed the policeman. “What have potatoes got to do with it?”

“They weigh a lot,” explained Paddington. “Especially King Edwards. If my vehicle started to roll down a hill I don’t know what I would do. I expect I would close my eyes in case it hit something and all the potatoes fell out.”

The policeman looked up from his keyboard and stared at Paddington. “I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that,” he said, not unkindly. “That sort of thing wouldn’t go down too well if it was read out in court. You might find yourself ending up in prison.

“Mind you,” he continued. “It’s probably on its way to the Czech Republic or somewhere like that by now.”

“The Czech Republic!” exclaimed Paddington hotly. “But it’s only just gone ten o’clock.”

“You’d be surprised,” said the man. “These people don’t lose any time. A quick going over with a spray gun. Who knows what colour it is by now. A new numberplate… On the other hand we don’t let the grass grow under our feet.” He picked up a telephone. “I’ll put out an all stations call.”

“I don’t have one of those,” said Paddington, looking most relieved.

“One of what?” asked the policeman, holding his hand over the mouthpiece.

“A numberplate,” said Paddington.

The policeman replaced the receiver. “Hold on a minute,” he said. “You’ll be telling me next you haven’t renewed your road tax…”

“I haven’t,” said Paddington. He stared back at the man with growing excitement. It really was uncanny the way he knew about all the things he hadn’t got.

“I’m glad I came here,” he said. “I didn’t know you had to pay taxes.”

“Ignorance of the law is no excuse,” said the policeman sternly. Reaching under the counter he produced a large card showing a selection of pictures.

“I take it you are conversant with road signs?”

Paddington peered at the card. “We didn’t have anything like that in Darkest Peru,” he said. “But there’s one near where I live.”

The policeman pointed at random to one of the pictures. “What does that one show?”

“A man trying to open an umbrella,” said Paddington promptly. “I expect it means it’s about to rain.”

“It’s meant to depict a man with a shovel,” said the policeman wearily. “That means there are roadworks ahead. If you ask me, you need to read your Highway Code again. Unless, of course…”

“You’re quite right,” broke in Paddington, more than ever pleased he had come to the police station. “I’ve never read it.”

“I think it’s high time I saw your driving licence.” said the policeman.

“I haven’t got one of those either,” exclaimed Paddington excitedly.

“Insurance?”

“What’s that?” asked Paddington.

“What’s that?” repeated the policeman. “What’s that?”

He ran his fingers round the inside of his collar. The room had suddenly become very hot. “You’ll be telling me next,” he said, “that you haven’t even passed your driving test.”

“You’re quite right,” said Paddington excitedly. “I took it once by mistake, but I didn’t pass because I drove into the examiner’s car. I was in Mr Brown’s car at the time and I had it in reverse by mistake. I don’t think he was very pleased.”

“Examiners are funny that way,” said the policeman. “Bears like you are a menace to other road users.”

“Oh, I never go on the road,” said Paddington. “Not unless I have to. I always stick to the path.”

The policeman gave him a long, hard look. He seemed to have grown older in the short time Paddington had been there. “You do realise,” he said, “that I could throw the book at you.”

“I hope you don’t,” said Paddington earnestly. “I’m not very good at catching things. It isn’t easy with paws.”

The policeman looked nervously over his shoulder before reaching into his back pocket.

“Talking of paws,” he said casually, as he came round to the front of the counter. “Would you mind holding yours out in front of you?”

Paddington did as he was bidden, and to his surprise there was a click and he suddenly found his wrists held together by some kind of chain.

“I hope you have a good lawyer,” said the policeman. “You’re going to need one. You won’t have a leg to stand on otherwise.”

“I shan’t have a leg to stand on?” repeated Paddington in alarm. He gave the man a hard stare. “But I had two when I came in!”

“I’m going to take your dabs now,” said the policeman.

“My dabs!” repeated Paddington in alarm.

“Fingerprints,” explained the policeman. “Only in your case I suppose we shall have to make do with paws. First of all I want you to press one of them down on this ink pad, then on some paper, so that we have a record of it for future reference.”

“Mrs Bird won’t be very pleased if it comes off on the sheets,” said Paddington.

“After that,” said the policeman, ignoring the interruption, “you are allowed one telephone call.”

“In that case,” said Paddington, “I would like to ring Sir Bernard Crumble. He lives near here. He’s supposed to very good on motoring offences. I don’t know if he does shopping baskets on wheels, but if he does, they told me in the market that he will have your guts for garters.”

The policeman stared at him. “Did I hear you say shopping basket on wheels?” he exclaimed. “Why ever didn’t you tell me that in the first place?”

“You didn’t ask me,” said Paddington. “I have a special licence for it. It was given to me when I failed my driving test in a car. They said it would last me all my life. I expect Sir Bernard will want to see it. I keep it in a secret compartment of my suitcase. I can show it to you if you like. At least, I could if I had it with me and I was able to use my paws.”

He stared at the policeman, who seemed to have gone a pale shade of white. “Is anything the matter?” he asked. “Would you like a marmalade sandwich? I keep one under my hat in case of an emergency.”

The policeman shook his head. “No, thank you,” he groaned, as he removed the handcuffs. “It’s my first week on duty. They told me I might have some difficult customers to deal with, but I didn’t think it would start quite so soon…”

“I can come back later if you like,” said Paddington hopefully.

“I’d much rather you didn’t…” began the policeman. He broke off as a door opened and an older man came into the room. He had some stripes on his sleeve and he looked very important.

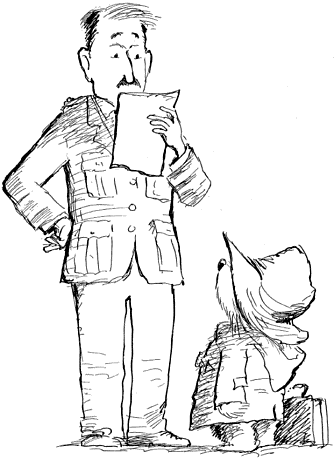

“Ah,” said the man, consulting a piece of paper he was holding. “Bush hat… blue duffle coat… Fits the description I was given over the phone… You must be the young gentleman who’s had trouble with his shopping basket on wheels.”

He turned to the first policeman. “You did well to keep him talking, Finsbury. Full marks.”

“It was nothing, Sarge,” said the constable, who seemed to have got some of his colour back.

“It seems there’s been a bit of a mix-up with the lads in the tow-away department,” continued the sergeant, turning back to Paddington. “They put your basket on their vehicle for safe keeping while they were removing a car and forgot to take it off again. It went back to the depot with them.

“They’ve put some fresh buns in it for you. Apparently, somehow or other, the ones that were in it got lost en route. Even now, the basket’s on its way back to where you left it. And there’s nothing to pay. What do you say to that?”

“Thank you very much, Mr Sarge,” said Paddington gratefully. “It means I shan’t have to speak to Sir Bernard Crumble after all. If you don’t mind, I shall always come here first if ever my shopping basket on wheels gets towed away.”

“That’s what we’re here for,” said the sergeant. “Although I think I should warn you; it may be a bit heavier now than when you first set out this morning.”

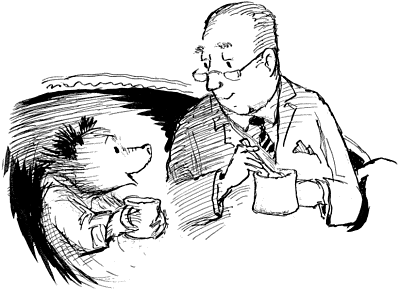

“Quite right too,” said Paddington’s friend, Mr Gruber, when they eventually sat down to their elevenses and Paddington told him the full story, including the moment when he got back to the market and found to his surprise that his basket on wheels was full to the top with fruit and vegetables.

“You have been a very good customer over the years and I dare say none of the traders want to see you go elsewhere. It is a great compliment to you, Mr Brown.

“All the same,” he continued, “it must have been a nasty experience while it lasted. If I were you, I would start your elevenses before the cocoa gets cold. You must be in need of it.”

Paddington thought that was a very good idea indeed. “Perhaps,” he said, looking up at the antique clock on the wall of the shop, “just this once, Mr Gruber, we ought to call it ‘twelveses’.”

Chapter Two

PADDINGTON’S GOOD TURN

LIKE MOST HOUSEHOLDS up and down the country, number thirty-two Windsor Gardens had its own set routine.

In the case of the Brown family, Mr Brown usually went off to his office soon after breakfast, leaving Mrs Brown and Mrs Bird to go about their daily tasks. Most days, apart from the times when Jonathan and Judy were home for the school holidays, Paddington spent the morning visiting his friend, Mr Gruber, for cocoa and buns.

There were occasional upsets, of course, but on the whole the household was like an ocean liner. It steamed happily on its way, no matter what the weather.

So when Mrs Bird returned home one day to what she fully expected to be an empty house and saw a strange face peering at her through the landing window, it took a moment or two to recover from the shock, and by then whoever it was had gone.

What made it far worse, was the fact that she was halfway up the stairs to her bedroom at the time, which meant the face belonged to someone outside the house.

She hadn’t seen any sign of a ladder on her way in; but all the same she rushed back downstairs again, grabbed the first weapon she could lay her hands on, and dashed out into the garden.

Apart from a passing cat, which gave a loud shriek and scuttled off with its tail between its legs when it caught sight of her umbrella, everything appeared to be normal, so it was a mystery and no mistake.

When they heard the news later that day, Mr and Mrs Brown couldn’t help wondering if Mrs Bird had been mistaken, but they didn’t say so to her face in case she took umbrage.

“Perhaps it was a window cleaner gone to the wrong house,” suggested Mr Brown.

“In that case he made a very quick getaway,” said Mrs Bird. “I wouldn’t fancy having him do our windows.”

“I suppose it could have been a trick of the light,” said Mrs Brown.