Полная версия

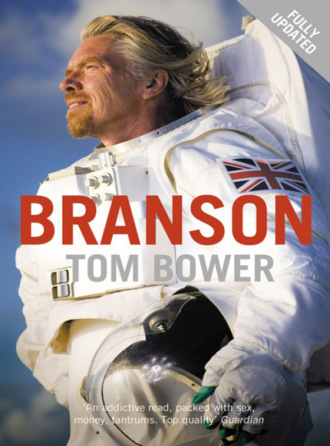

Branson

Once again in his office, speaking again between telephone calls, Branson admitted there was a problem. ‘It’s so close to the deadline I can’t arrange it in the time. It normally takes three weeks.’ Oliver became visibly distressed. ‘But I could pull some strings,’ offered Branson, ‘if you would do a favour for me.’ The businessman’s proposition was simple.

‘BBC TV,’ he explained, ‘are featuring me in a programme called “Tomorrow’s People”. They want to feature my Student Advisory Centre. If you agree to be filmed visiting me, I’ll pull strings and fix up your abortion.’

‘But I don’t want anyone to know about me,’ said Oliver. ‘I want secrecy.’

‘Well, wear a disguise,’ suggested Branson.

‘Is there no other way?’ she asked.

‘There’s nothing else I can do. Think about it.’

Four days later, Oliver believed she had no option but to agree. ‘Great,’ said Branson. ‘Come to my office. We’ll be filmed and then we’ll go straight to Birmingham.’ Their destination was the Pregnancy Advisory Centre, a respectable organisation which had agreed to the filming. The documentary, celebrating Branson as a rising personality, was transmitted shortly afterwards. Oliver’s disguise, a wig, was ineffective. Branson appeared unaware of her embarrassment. His name, though, was increasingly mentioned among the lists of fashionable youth.

Benefiting from other people’s labour and ideas hardly matched the image of the sixties rebel but his style encouraged Branson’s trusting tenants and employees to literally plonk ideas on his bed. One morning, as he sat in bed with Mundy Ellis talking simultaneously on two telephones and reaching for papers, Tom Newman entered. Tall, long haired with a hint of cool mystery which attracted women, Newman was the stereotype rock guitarist: an uneducated rake immersed in drugs, sex and rock and roll. Bobbing on the fringes of the music world after graduating from bruising battles with bikers at the Ace Café, he relied upon others to pull his life together after fleeing his home and his father, a drunken Irish salmon poacher. Newman felt socially inferior to the younger Branson described by his girlfriend, an employee of Virgin Records, as ‘fascinating but tyrannical’.

‘Why don’t you build your own recording studio?’ asked Newman. ‘You could make a lot of money from that. I’ll run it.’

‘Sounds good,’ stuttered Branson as Mundy dropped a grape into his mouth. Quickly Branson warmed to the idea. He encouraged Newman’s trust. ‘He was the first bloke I ever spoke to who spoke posh,’ Newman told a friend. ‘But he was approachable, charming and keen.’

‘Let’s find a studio,’ Branson agreed, conjuring visions of a music empire.

Like generals in battle, putative tycoons also rely upon luck. In January 1971, Simon Draper, a twenty-one-year-old second cousin, introduced himself in South Wharf Road. ‘I’ve just arrived from South Africa,’ he smiled. Over breakfast, as Branson excitedly unveiled his ambitions to own a record label and a chain of record shops, Draper revealed his encyclopaedic knowledge of modern music. Even better for Branson, his unknown cousin, like Steve Lewis, was more interested in music than money. Branson, who confessed that his favourite tune that week was the theme from Borsalino, recognised that Draper’s arrival was a godsend. Draper was invited to join the empire and work with Nik Powell, a childhood friend of Branson’s and his neighbour in Surrey. In return for leaving university prematurely, Powell had negotiated with Branson a 40 per cent stake in Virgin Music which embraced Virgin Records.*

Powell was a perfect complement to Branson. Quiet, cerebral and unimpulsive, he imposed order on the chaos of Branson’s stream of initiatives, restrained his friend’s excesses and managed the ramshackle finances of a business not even incorporated within a company. Carefully set apart from other employees, Branson, Draper, Powell and a few other public school friends formed a tight cabal.

Powell’s organisation, Branson acknowledged, had saved Virgin’s mail-order business from the destruction threatened when the postal workers went on strike. Together, they had rapidly opened a record shop in Oxford Street. ‘We’ll put an ad in Melody Maker,’ suggested John Varnom, ‘about lying on the floor, listening to music, smoking dope and going home.’

‘Great,’ laughed Branson. Nothing more was said or expected. Branson often communicated only in monosyllables. Miraculously, dozens of admiring customers regularly queued to enter the first-floor shop. Long-haired hippies slouched on waterbeds listening to music on headphones while others waited outside to enter. A truth had dawned on Branson. Most people were born to be servants and customers. He would be master, provider and richer.

The increasing flow of cash from the record sales and the growing popularity of Virgin among music fans encouraged Branson’s dreams of expansion. Profiting from his employees’ agreement to earn just £12 per week, Branson was secretly accumulating a fortune. Rifling through Branson’s desk, John Varnom had discovered a building society cash book showing a £15,000 deposit in the name of Richard Charles Nicholas, Branson’s three Christian names. ‘Cheeky bastard,’ whispered Varnom. Even in 1970 Branson’s finances were attracting controversy. Private Eye reported that Branson had received £6,000 for advertisements in Student but only admitted to £3,000, which Branson vigorously denied. Indeed there was no evidence that he had. Varnom said nothing about the cash book. The amount was too large to envy and the notion of equality, Varnom knew, was bogus. Besides, he knew no better alternative to working and living in Branson’s kingdom, especially after the realisation of Tom Newman’s idea.

The search for a recording studio had terminated in March 1971 at a seventeenth-century Cotswold manor house in Shipton, five miles from Oxford. The price was £30,000. ‘How are you going to pay for it?’ asked Newman, mystified. Branson smiled enigmatically. ‘You’re an imperialist,’ Newman, a rocker without a bank account and unaware of overdrafts, grunted. He remained puzzled how a twenty-one-year-old hippie could find the present-day equivalent of £275,000 while his employees were earning £12 per week. The unspoken explanation was Branson’s unique fearlessness about debt. Money was unthreatening to a man certain of success who assumed that risk would be rewarded.

To buy and convert the manor and outhouses into bedrooms and a recording studio required capital. Branson approached an aunt for a gift. She was advised by her stockbroker to offer only a loan. Branson received £7,500, a sufficient sum for an application to Coutts, the bank shared by the Bransons and the royal family, to advance a mortgage for the remainder. The trusting bankers, reassured by the Branson family’s reputation, did not question Virgin’s cash flow from the shop and mail-order business, or discover the purchase tax fraud and the sale of bootleg records. Even after his arrest, there was no unpleasantness between the bankers and their client.

As for the £60,000 tax payments and fines, his cabal assumed the same Masonic relationships which had saved Branson from conviction and public humiliation would arrange the money. None could imagine that his imminent collapse could be forestalled only by a bravura performance.

‘On my life,’ Branson bluffed to his creditors, ‘Virgin’s finances are fine.’ The company, he repeated, was not in financial peril. The flow of cash from fifteen new Virgin record shops opened across the country substantiated the denials of fragility. Branson and Powell precisely timed the opening of each shop in a different town to secure interest-free cash for two months before payments were required. Other sources of income remained undisclosed. Walking a tightrope was intoxicating but the chaos had become perilous. Virgin Records was not incorporated as a company. Branson had forgotten the legalities. His employees paid neither tax nor national insurance. For four years, he had been trading without proper financial accounts. Bereft of cash, Branson was perplexed how to equip Tom Newman’s recording studio at the manor. ‘Let’s play roulette at the Playboy Club in Park Lane,’ he suggested to Newman. ‘I’ve got a winning system.’ Using £500 taken that night from the till of Virgin’s shop in Notting Hill Gate, he and Newman shuttled between two tables as Kristen Tomassi, his blonde American girlfriend, gazed with increasing bewilderment. ‘It’s the last bet,’ Branson gritted at 5 a.m., clutching a few chips. He had risked everything; his system had failed. The flick of the wheel was lucky. ‘Great,’ he sighed as he stepped into Park Lane with £700. Before the shop opened later that morning, the original money was restored and the profits divided with Newman. Twenty-five years later he could speak from experience that the National Lottery compared to the roulette wheel was ‘a licence to print money’.

Tom Newman’s enthusiasm, Branson discovered, was not matched by his technical expertise. The guitarist knew little about the technology of recording music. For reassurance, Branson consulted George Martin, the Beatles’ producer. Martin laughed. Branson was proposing a four-track studio while Martin was installing sixteen tracks and much more. ‘We can’t afford all that,’ Branson told Newman. ‘We’ll have to busk it.’ They would buy second-hand equipment and Newman would learn on the way. ‘I’ve found some cheap mixers and old speakers,’ announced Newman proudly. ‘But the acoustics won’t be much good.’

‘Keep quiet about it,’ ordered Branson.

‘The best sound you can get,’ Branson boasted to musicians and their managers in a frenzy of telephone calls and personal visits to lure the unwary. ‘Sell them the image,’ suggested John Varnom, the inventor of the Virgin name. ‘Act the part of the alternative. No suits and ties like Decca.’ Compared to the unfriendly basements hired by the big studios in London, the manor offered a party. Unlimited meals and alcohol served in manorial splendour by four attractive girls, with the promise of huge bedrooms upstairs, created the illusion of a sex hotel with nightly orgies where drugs were served with the cornflakes. In truth, there was less actual sex at the manor than occurred in London nightclubs but Branson calculated that the promise of a party would conceal the inferior quality of the sound and enhance his profits. His intuition proved shrewd.

Branson persuaded Newman and the eager girls to accept low wages. Newman’s screaming protests when Branson frequently failed to send any money were brushed aside. ‘I’m also not being paid,’ lamented Branson, the victim. None of the uninquiring spirits enjoying his company realised that the principal beneficiary of their own low wages was Branson, focused entirely on his own agenda.

Circulating among his staff in the Sun in Splendour, the local pub on Portobello Road, puffing their cigarettes, sipping their beer and groping the girls amid jovial banter eased suspicions about an ambitious businessman. Touchy-feely embraces, pecking at cheeks and spasms of generosity defused the impression of a hierarchy and encouraged the notion of the Virgin family. Employment at Virgin, Branson had persuaded himself and his loyal staff, was benign, generous and equitable.

Occasionally providing a company car, invitations for meals in restaurants and organising holidays for some staff, he was the life and soul of his own party. Acting the fool in front of big audiences, skiing naked down alpine slopes and hosting hilarious mystery away-days terminating in Croydon solidified loyalty and trust in him. For those condemned to dreary office lives, Branson offered the chance to sense magic. Only the cabal, those close to Branson, understood that their garrulous host had created the family as protection from loneliness. Branson required perpetual company to protect himself from boredom. The anti-intellectual was incapable of self-entertainment. But his permanent party could not continue unchecked.

One year after the exposure of his purchase tax fraud, Branson was compelled to abandon the convenience of concealment through chaos. ‘You’ll have to become directors of proper companies,’ Jack Claydon, an accountant, told Branson. In September 1972, Virgin Records was incorporated and over the following months ten other companies were created. Legal compartmentalisation suited Branson’s instinct for secrecy and provided the machinery to transfer money from one company’s account to another’s, giving the appearance of solvency and preventing bankruptcy in one activity infecting the whole business. ‘I’m spending a lot of my time,’ Jack Claydon told a friend, ‘juggling banks and creditors in order to play one off against the other and help Branson to stay solvent.’ Claydon, an inconspicuous character, was ideal for many discreet shuffles.

Telephoning early in the morning, Branson summoned the accountant to his houseboat. Unlike a previous call when Branson had even had to ask for advice where to find a hooker for an American contact, Claydon was asked to give respectability to Branson’s latest venture. ‘I’m going to sign a deal and I need a letter to the bank to borrow more money.’ Claydon’s task was to bestow credibility on Branson’s optimistic financial projections of sales and profits. ‘Make it look good,’ urged Branson.

‘The bank wants to meet us,’ Claydon reported later that day.

Lunch with Peter Caston, his bank manager, at Simpsons was Branson’s opportunity to shine. Wearing a suit and tie, his enthusiastic projections of wealth were only marred, despite Claydon’s warning glances, by excessive talking. The conservative banker was bewildered and became cautious, especially after Branson’s cheque for lunch was rejected. The guest from Coutts reluctantly paid. Branson’s strength was his robust refusal to accept defeat. ‘You’re never morose,’ said Claydon in grudging admiration of a man whose energy exceeded conventional business talent. ‘You’ll always find an escape.’ Branson laughed. Claydon even urged him to ‘stop interfering in the business’ to avoid creating chaos. The accountant, whose audit validated the Virgin business, thankfully did not understand that chaos was an essential to Branson’s appearance as a classless wealth creator. Parroting the sixties mantra about ‘helping to make the world a better place’ concealed a more straightforward ambition: that it should be a better place for Richard Branson.

* Not her real name.

* Throughout the book Virgin Records is not distinguished from the Virgin Music Group.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.