Полная версия

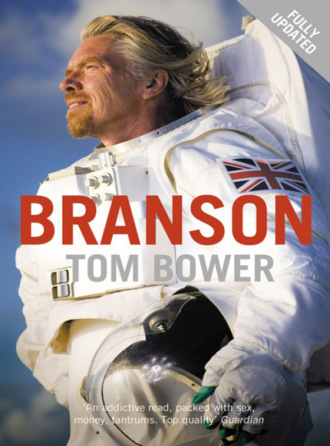

Branson

TOM BOWER

BRANSON

Dedication

To Jennifer

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Preface to the 2008 edition

Introduction

1 The crime

2 The beginning

3 Honeymoons and divorces

4 Frustrations

5 Dream thief

6 The people’s champion

7 Confusion and salvation

8 Returning to the shadows

9 Finding enemies

10 War and deception

11 Sour music

12 Double vision

13 Unfortunate casualties

14 The underdog

15 Another day, another deal

16 Another day, another target

17 The cost of terrorism

18 Sinking with dinosaurs

19 Honesty and integrity

20 Indelible tarnish

21 A slipping halo

22 Fissure

23 Squeezing friends

24 ‘House of cards’

25 Seeking salvation

26 An enduring suspicion

Postscript – 2008

Sources

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

On 16 December 1998, Sir Richard Branson was preparing to set off from Marrakesh in an attempt to become the first person to circumnavigate the world in a hot-air balloon. Over the previous days I had sought to join his party in Morocco to witness a Branson extravaganza. I was still undecided whether to write a book about Branson but expected that the experience might influence my decision. That morning, my place on Virgin’s chartered jet on behalf of a national newspaper was suddenly cancelled.

To my surprise, at lunchtime the same day, I received a brutal, defamatory and untrue letter from Branson, whom I had never met, faxed by his London office. Branson alleged that he had received ‘a number of calls over the last six weeks from various friends and relatives who have been upset by your researchers/detectives’. He claimed that on my behalf these hired hands had ‘doorstepped’ a woman and uttered ‘untrue accusations that her son is, in fact, my son’. Not surprisingly, he continued, that behaviour had ‘caused a lot of upset to all the people concerned including the real father’. Since those same people were flying to Marrakesh for the launch of the balloon, he felt it would be ‘inappropriate’ for me to be present. ‘To be perfectly honest,’ he added, ‘none of them would particularly welcome it.’ Branson concluded that after the trip was completed we could discuss ‘what exactly it is you are after’.

I was flabbergasted by Branson’s letter. I had never heard of the people he mentioned. I had not employed any detectives nor had I asked or heard of anyone doorstepping these people. In a faxed reply, I immediately protested.

Three days later, I received a response. In an unexpected call to my mobile phone, an unfamiliar voice announced, ‘Tom, I’m sorry about that.’

‘Who is that?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘It’s Richard,’ he replied.

‘Richard who?’

‘Richard Branson.’

‘But I thought you were in a balloon.’

‘I am.’

‘Where are you?’

‘Dunno,’ he replied and could be heard asking about his location. ‘Over Algeria,’ he continued and then said, ‘Look, I’m sorry. When I get back, let’s meet and talk things through.’

His bizarre behaviour persuaded me that the real Branson, his methods and his operation remained, despite all the publicity, unknown.

About ten weeks earlier, a tiny announcement in an obscure part of the Financial Times about a management resignation from Victory, Branson’s new clothing corporation, had alerted my curiosity. The senior director, the newspaper’s four-line report recorded, was departing after just five months because ‘there was no role for an executive chairman’.

Branson’s new company, I knew, was spiralling into debt. The management change could only have been caused by anxiety. Virgin’s official denials of problems fuelled my suspicions.

Hence, in January 1999, I began this book. Despite his suggestion that we should meet, I never heard from Branson personally, though I soon became aware of his attitude. Several people I approached for interviews told me that, ‘after checking’, they would prefer not to meet. I had the distinct impression that Branson or the Virgin press office was discouraging people. From other comments, it appeared that Branson was unwilling to either help or meet me.

On 22 October 1999, having made substantial progress, I nevertheless wrote to Branson asking ‘whether you would reconsider your position and agree to meet?’ On 6 December, explaining that my letter had only just arrived, he replied: ‘I have been called by a large number of people who you have interviewed about me. Most told the same story, namely that you have a fixed agenda and that no amount of persuasion or argument by them to the contrary appeared to have any influence on you. As it would therefore appear that you have pre-judged me, it would seem that little benefit or pleasure would come from our meeting.’

That was, I believed, impolite and inaccurate. By then, I had interviewed over two hundred people. Many were his sympathisers. I had deliberately sought their opinions to produce an objective book. Certainly, I posed as a devil’s advocate in testing his admirers’ opinions. The technique is reliable and is even favoured by Sir Richard himself. But there was no justification for concluding that my questions confirmed prejudice. On the contrary, I had striven to understand a man who declined my attempts to meet to hear his opinions.

In his letter of 6 December 1999, Branson did offer to answer any written questions and also requested to read the manuscript of the book. He would later express himself to be ‘very disappointed’ that I had not allowed him to vet and approve this book prior to publication.

On 11 January 2000, I submitted nine questions. On 18 February, he sent his replies. They contained one serious error, namely about the circumstances and timing of a Japanese investment in Virgin Music in 1989. The significance of Branson’s error will become apparent to the reader at the beginning of this book.

By February 2000, however, the relationship between Branson and myself had become complicated. Branson was upset by an article I had written in December 1999 in the Evening Standard about his bid for the National Lottery. He believed my comments to be defamatory.

As we exchanged letters about the article and I replied to his threat of commencing legal proceedings if I failed to publish an apology, I was reminded about his letter to the Spectator on 28 February 1998 protesting about another journalist, where he recorded, ‘I have never sued anyone to suppress criticism of myself or Virgin.’ Two years later, on 22 March 2000, that boast became redundant.

In an operation seemingly co-ordinated with The Times, a leather-clad motorcyclist served a writ issued by Branson while I was answering questions from a journalist who happened to telephone at the precise moment the writ was served. Branson’s action was considered of such importance that The Times prominently reported the writ on its front page the following day.

Of the many unusual aspects of Branson’s resort to legal action, few were more significant than his decision to sue me exclusively and not, as is customary, also the newspaper which published the article. Branson’s decision to deliberately exclude the newspaper was interpreted by my legal advisers as an attempt to undermine the publication of this book. The plan was obvious.

Confronted by the impossibility of matching Branson’s self-proclaimed fortune to finance a team of lawyers, I would have been forced to capitulate and apologise, and inevitably discredit my own book. Fortunately, Max Hastings, the Evening Standard’s editor, pledged in a prominent article to finance the defence of the piece which his newspaper had published.

At the time I wrote this book, there had been two biographies and one autobiography about Richard Branson. All three benefited from Sir Richard’s vetting and approval. I resisted that blessing. This book is offered as a balanced review of Britain’s most visible entrepreneur, an eager recipient of hero worship, trying to influence practically every aspect of British society, who, in his attempt to market a Virgin lifestyle, seeks the widest possible circle of influence.

Preface to the 2008 Edition

Sir Richard Branson did not appreciate this unauthorised biography when it was originally published in 2000. Indeed, to prevent its publication, he took exception to a critical article which I had written for the London Evening Standard about his first bid for the National Lottery, and decided to issue a writ for defamation against myself, but not against the newspaper. Some interpreted this as an attempt to put me under financial pressure to settle the case in his favour. Had it succeeded, the credibility of this biography would have been destroyed even before its publication. Eventually, without my having offered any concession or agreeing to any of his demands, Sir Richard withdrew his complaint and his case was abandoned. The legacy was twofold. The rulings by Mr Justice Eady and the Court of Appeal during the lengthy hearings of Branson vs Bower have become enshrined as a cornerstone of British libel law. Newspapers, publishers, journalists and authors are, in some circumstances, now protected in publishing critical comment so long as the author wrote in good faith.

The second legacy was the generation of enormous publicity, which propelled the success of this book. Following his recent successes in the libel court, Sir Richard had apparently anticipated another scalp. Yet over the following months many concluded that he had scored a spectacular own-goal.

Throughout the world, those interested in the Branson phenomenon were alerted to an alternative interpretation of a remarkable career. Over the past eight years I have received a steady stream of enquiries and congratulations as a result of this biography of the controversial tycoon. With some nostalgia I recall listening to BBC Radio 4’s World at One and hearing Sir Richard’s triumphant boast outside the Royal Palaces of Justice in Fleet Street after his libel victory against Guy Snowden, the chairman of Camelot, a rival bidder for the original lottery licence. ‘My mother taught me to always tell the truth,’ Branson told his excited audience.

This book was to cast an objective interpretation on his career just as his bid for the National Lottery was being reconsidered after a bitter court case. To Branson’s distress, the original decision to award him the lottery licence was overturned. Partly, he knew, this book’s revelations had turned opinion against him. Now, eight years later, Branson’s recent activities, self-promotion and solecisms, especially during his bid for the distressed bank Northern Rock, have warranted an updated version of the original book.

Over the past eight years I have occasionally been invited to write articles for newspapers about Branson. Each article automatically provokes Branson to complain about ‘multiple inaccuracies’ and demand the publication of his version of the truth. Invariably, identical facts provoke starkly different interpretations. My articles published during his bid for Northern Rock especially provoked his ire. I did not think that his controversial past justified the government’s original decision to entrust over £50 million of taxpayers’ money to the Virgin group. For whatever reason, the government finally agreed with me. The loss of Northern Rock could be as grave a blow to Branson’s fortunes as his failure to win the Lottery licence.

Sir Richard nevertheless remains one of the world’s most popular tycoons. Countless ambitious and intelligent young people, aspiring to become successful businessmen, voraciously read his autobiography and other publications in their attempts to understand the secret of his success. If they believe that his version is the Holy Grail, they are mistaken. During my own career following the lives of other tycoons including Robert Maxwell, Mohamed Fayed, Tiny Rowland, Geoffrey Robinson and Conrad Black, one common denominator has always emerged. An important element of their success has been the myths generated to conceal their aggressive journeys up the greasy pole. Similarly, once they bask in the spotlight, they share a brazen aggression to maintain their version of the ‘truth’ against those posing honest questions. However outstanding a personality Branson may be, he is weakened by his forceful attempts to silence his critics and his victims; and it is the latter, his hapless business partners, who remain frustrated by his remorseless success.

Eight years ago, Branson had reached a precipice, and his empire’s prosperity was endangered. Brilliantly, his juggling snatched victory from possible defeat. Now, once again, his fortunes are challenged. Whether he can stage another resurrection is a tantalising question. The Branson rollercoaster never stops.

Tom Bower

London, July 2008

Introduction

In early June 1988, Ken Berry, a discreet director of the Virgin Group, arrived in Tokyo on a secret assignment. Berry, a deal-maker trusted by Richard Branson, was searching for $150 million.

Although Virgin Music was a publicly owned company, Richard Branson preferred not to reveal Berry’s mission to his British shareholders and his two non-executive directors.

Berry had arranged to meet Akira Ijichi, the president of Pony Canyon, a subsidiary of a giant Japanese media company. Their introduction at the Intercontinental Hotel in the Shinjuku district lasted two hours.

‘This meeting has got to remain secret,’ stipulated Berry. Ijichi nodded his agreement. Berry continued: ‘Virgin needs money to expand. We’re looking for $150 million.’ That was not the complete reason for Berry’s search for money.

Three months later, in September, Akira Ijichi arrived in London with his translator Moto Ariizumi, a junior executive in the company. Both stayed at the Halcyon Hotel, in Holland Park, conveniently close to Branson’s home. By then, their New York bankers had undertaken an external examination of the Virgin Group’s business and finances. Negotiations, the bankers had suggested, should start at $125 million for a 25 per cent stake.

Berry, a natural deal-maker, could sense Ijichi’s enthusiasm. The Japanese was flush with cash. During their discussions in Virgin’s offices on the Harrow Road, Berry emphasised on several occasions, ‘We don’t want any publicity. We don’t want the shareholders to know.’ The secrecy suited the Japanese: they wanted the deal to succeed.

Later, at the end of their second day in London, the two Japanese met Richard Branson for dinner at his home. Their host was charming but firm: ‘The company’s worth $600 million. Not a dollar less.’ Ijichi nodded.

The following morning, the two Japanese were welcomed by Branson on his houseboat in Little Venice. Amid the stripped pinewood floors, cane furniture and leafy plants Branson shone, in Moto Ariizumi’s opinion, as a ‘quite extraordinary but fashionable’ representative of the alternative culture.

Before their departure, Akira Ijichi agreed to pay $150 million for a 25 per cent stake although several important details remained unresolved. Branson and Berry were untroubled by the delay. In the meantime, Branson had dramatically announced his decision to privatise the Virgin Group. His unexpected decision to buy back the shares from the public had caused considerable surprise although everyone was grateful that he valued the Virgin Group at £248 million, double the stock market’s value. However, when Virgin’s shareholders met in November 1988 to formally approve Branson’s proposed privatisation, neither the shareholders nor Virgin’s two non-executive directors were aware of Berry’s continuing negotiations with the Japanese. If the shareholders had known about Pony Canyon’s agreement that the Virgin Group was worth $600 million, or £377 million – £129 million more than the sum offered to shareholders – they might have demanded that Branson buy back the shares at the same valuation.

Pony Canyon’s investment was formalised in May 1989. The public would remain unaware that the relationship had been initiated before Branson’s announcement of the privatisation.

Within two years, Virgin’s status would be utterly transformed. Branson was hailed as a genius after selling Virgin Music for £560 million or $1 billion. Since his deal with Akira Ijichi, Branson had doubled his fortune and become one of a rare breed: a legend in his own lifetime, an icon and a billionaire.

Eight years later, on 8 November 1999, Branson was invited as a British hero to deliver a Millennium Lecture at Oxford University. The Examination Room was packed with admirers, students and elderly academics. Mr Cool Britannia, the blameless face of New Britain, was introduced by Lord Butler, the former Cabinet Secretary, as ‘a lighthouse for enterprise who owns 150 companies and all of them are profitable’. Branson, dressed casually in his characteristic pullover, smiled. He knew that Butler’s praise was inaccurate. With the exception of his airline and rail franchises, all of his major companies in 1999 were trading at a loss.

Branson was rarely asked to face unpleasant contradictions. Voted Britain’s favourite boss, the best role model for parents and teenagers, and the most popular tycoon, he was widely admired by most Britons. Branson, the public believed, was at heart a charitable public servant whose companies just happened to earn handsome profits. Idealism was his business.

The opening of Branson’s sermon to his young idolaters in Oxford emphasised the irrelevance of education. Only those rejecting university would become millionaires, he preached.

His second theme foretold the future of industry: it was dead. ‘Don’t go into industry to make money,’ he urged. Manufacturers with assets would soon be worthless. ‘Focus on customers,’ was his gospel. Only brands would be valuable in the future. ‘I believe there’s no limit to what a brand can do,’ he enthused. Expertise was also worthless: ‘If you can run one business, you can run any business.’ He personally had known little about the music and airline businesses, the sources of his two fortunes, which naturally led to his third article of faith urged on his audience: ‘get the right people around you and just incentivise them’. His secrets of success were bold and liberating to an audience unaware of Branson’s increasing inability to attract and retain the brightest young brains.

His admirers in the audience sought from Branson an inspiring vision for his personal and Britain’s future prosperity. ‘What,’ one asked, ‘is your major ambition in the new millennium?’ The hero paused. Bill Gates would have anticipated the next generation of developments of the computer and the internet. Rupert Murdoch, whom Branson once aspired to overtake, would have expounded the future of global communication. But Branson avoided such complicated speculations. The icon’s face assumed the countenance of destiny as he intoned his reply: ‘To run the national lottery.’ Branson gazed thoughtfully across the hundreds of placid faces, unaware of the frisson of disappointment which enveloped his audience.

Aspiring tycoons in the hall, regarding Branson as a model for ‘shaking up industries and offering a better product’, were fed a simplistic, reductive homily from Britain’s greatest entrepreneur. To create real wealth, they were urged by the acceptable face of capitalism, rely on a label. Ignore education, ignore expertise and ignore technology. In a citadel of academic excellence, Branson had preached anti-knowledge. The new generation, he urged, should believe that sustainable businesses could be created without ‘a great business plan or strategy. Just instinct.’

The generational division among those inside the Examination Hall was blatantly evident. To those dozens of students, eager to shake their hero’s hand, proffering scraps of paper for his autograph, Branson’s self-generated image of a buccaneer bestriding his own world was laudable. They admired the champion of the underdog who advertised himself as a product. He was the admirable, fun-loving millionaire.

The older, more sceptical members of the audience, as they slipped out of the hall for a glass of sherry in the Master’s lodgings, mentioned a fallacy. Unlike Bill Gates, they murmured, Branson’s fortune was forged on old ideas that ignored innovation. The result was, they sniffed, self-evident. While Bill Gates’s fortune was valued at $100 billion and constantly rising, Richard Branson’s wealth was a disputed $3 billion and possibly falling.

Three days later, on 11 November 1999, in Leicester Square, London, Branson was sitting on a bright red sofa in a huge Perspex container fixed on a trailer. Six naked young girls were grouped around the master of self-promotion. His latest extension of the brand was Virgin Mobile, a belated bid to join the New Economy developed and dominated for some years by Vodafone, Cellnet and others. Branson never paused to contemplate the relevance of six naked girls clutching mobile telephones to herald his entry into the New Age. Nor was he concerned that his latest marketing stunt technically broke the law. Securing free advertising in the following day’s tabloid newspapers was his sole ambition. ‘Public relations is an important part of running our business,’ Branson once explained. ‘About 20 to 25 per cent of my time is spent on PR.’ No one sold Branson like Branson. His business skills included the publicity skills of a salesman unafraid to yell for attention in a market even if, as he had confided to his Oxford admirers, he lacked any presence or expertise.

Seeing a policeman striding across Leicester Square, Branson abruptly abandoned the naked girls and scurried to a waiting taxi. While the girls were ordered to dress, Branson had time to reflect that it was just another ordinary day, promoting himself and his ambitions.

‘We intend to sell 100,000 telephones by Christmas,’ he pledged that morning, emphasising Virgin’s core values of quality and fun. ‘And one million by Christmas next year.’ By January 2000, just over 100,000 telephones had indeed been sold, although the figure included 20,000 offered at a discount to Virgin employees and their families, but four weeks later Virgin’s telephone network temporarily collapsed. The Virgin brand, promoted by himself as a ‘global business’, was limping. Anti-knowledge, balanced on the edge of a financial precipice, was an uncertain guarantee for success.

Later on the same day as the launch of the Virgin Mobile, Branson was swigging a bottle of beer at a good humoured promotion party for one thousand young men and women advertised as ‘Very Sexy. Very Decadent.’ A constant flow of admirers sought a few minutes in his company and the opportunity for a photograph. All were attracted by his courage, his blokeishness and his social conscience. The ‘daredevil’s’ oft repeated ambition to ‘make the world a better place’ appealed to those attracted by a pleasant, friendly and unthreatening superstar. Calmly, he stood beside his wife, Joan, personifying the Virgin Dream. At 10.15 p.m., his wife signalled their departure. Outside, a car waited to drive the Bransons to their two adjoining houses in Holland Park worth £10 million. One house, after a recent fire, was for sale. A portent, some unkind observers carped, of the fate of a man who, after thirty years within the warm embrace of tabloid headlines, had become unexpectedly imperilled.