Полная версия

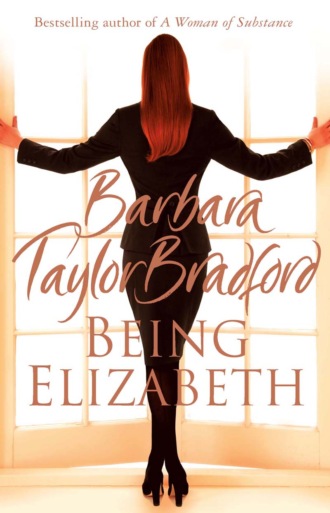

Being Elizabeth

‘What is it? You’re staring at me in the most peculiar way,’ said Elizabeth, and walked into the study, her expression one of puzzlement.

‘Three peas in a pod,’ Cecil answered with a faint laugh. ‘That’s what I was thinking as you stood there in the doorway. The sunlight was streaming in, and the marked resemblance between you and your father and great-grandfather was … uncanny.’

‘Oh.’ Elizabeth turned around, her eyes moving from the portrait of her father to the one of her great-grandfather, the famous Edward Deravenel, the father of Bess, her paternal grandmother. It was he she admired the most, he who had been the greatest managing director of all time, in her opinion … the man she hoped to emulate. He was her inspiration.

‘Well, yes, I guess we do look as if we’re related,’ she answered, her black eyes dancing mischievously. Taking a seat opposite Cecil, she went on, ‘Just let’s hope that I can accomplish what they did.’

‘You will.’

‘You mean we will.’

He inclined his head, murmured, ‘We’ll do our damnedest.’

Shifting slightly in the chair, Elizabeth focused her eyes on Cecil with some intensity, and said slowly, ‘What are we going to do about the funeral? It will have to be here, won’t it?’

‘No other place but here.’

‘Have you any ideas about who we ought to invite?’

‘Certainly members of the board. But under the circumstances, I thought it was a good idea to turn the whole thing over to John Norfell. He’s one of the senior executives, a long-time member of the board, and he was a friend of Mary’s. Who better than him to make all the arrangements? I spoke to him a short while ago.’

Elizabeth nodded, a look of relief on her face. ‘The family chapel holds about fifty, but that’s it. And I suppose we’ll have to feed them –’ She shook her head, sighing. ‘Don’t you think it should be held in the late morning, so that we can serve lunch afterwards and then get them out of here around three?’

Amused, Cecil began to chuckle. ‘I see you’ve already worked it out. And I couldn’t agree more. I hinted at something of the sort to Norfell, and he seemed to acquiesce. I doubt that anyone even really wants to come up here in the dead of winter.’

She laughed with him and pointed out, ‘It’s so cold. I put my nose outside earlier, and decided not to take a walk. God knows how my ancestors managed without central heating.’

‘Roaring fires,’ he suggested, and glanced at the one burning brightly in the study. ‘But to my way of thinking, fires wouldn’t have been enough … we’ve got the central heating at its highest right now, and it’s only comfortable.’

‘That’s one of the great improvements my father made, putting in the heating. And air conditioning.’ Rising, Elizabeth strolled over to the fireplace, threw another log on the fire, and then turning around, she said quietly, ‘What about the widower? Do we invite Philip Alvarez or not?’

‘It’s really up to you … but perhaps we should invite him. Out of courtesy, don’t you think? And look here, he was always well disposed towards you,’ Cecil reminded her.

Don’t I know it, she thought, remembering the way her Spanish brother-in-law had eyed her somewhat lasciviously and pinched her bottom when Mary wasn’t looking. Pushing these irritating thoughts to one side, she nodded. ‘Yes, we’d better invite him. We don’t need any more enemies. He won’t come though.’

‘You’re right about that.’

‘Cecil, how bad is it really? At Deravenels? We’ve touched on some of the problems these last couple of weeks, but we haven’t plunged into them, talked about them in depth.’

‘And we can’t, not really, because I haven’t seen the books. I haven’t worked there for four and a half years, and you’ve been gone for one year. Until we’re both installed, I won’t know the truth,’ he explained, and added, ‘One thing I do know though is that she gave Philip a lot of money for his building schemes in Spain.’

‘What do you mean by a lot?’

‘Millions.’

‘Pounds sterling or euros?’

‘Euros.’

‘Five? Ten million? Or more?’

‘More. A great deal more, I’m afraid.’

Elizabeth came back to the desk and sat down in the chair, staring at Cecil Williams. ‘A great deal more?’ she repeated in a low voice. ‘Fifty million?’ she whispered anxiously.

Cecil shook his head. ‘Something like seventy-five million.’

‘I can’t believe it!’ she exclaimed, a stricken look crossing her face. ‘How could the board condone that investment?’

‘I have no idea. I was told, in private, that there was negligence. Personally, I’d call it criminal negligence.’

‘Can we prosecute someone?’

‘She’s dead.’

‘So it was Mary’s fault? Is that what you’re saying?’

‘That is what has been suggested to me, but we won’t have the real facts until we’re in there, and you’re managing director. Only then can we start digging.’

‘It won’t be soon enough for me,’ she muttered in a tight voice. Glancing at her watch, she went on, ‘I think I had better go and change. Nicholas Throckman will be arriving here before we know it.’

Elizabeth was in a fury, a fury so monumental she wanted to rush outside and scream it into the wind until she was empty. But she knew it would be unwise to do that. It was an icy morning and there was a bone-chilling wind. Dangerous weather.

And so instead she rushed upstairs to her bedroom, slammed the door behind her, fell down on her knees and pummelled the mattress with her fists, tears of anger glistening in those intense dark eyes. She beat and beat her hands on the bed until she felt the anger easing, dissipating, and then suddenly she began to weep, sobbing as if her heart was breaking. Eventually, finally drained of all emotion, she stood up and went into the adjoining bathroom where she washed her face. Returning to the bedroom she sat down at her dressing table and carefully began to apply her make-up.

How could she do it? How could she tip all the money into Philip’s greedy outstretched hands? Out of love and adoration and wanting to keep him by her side? The need to keep him with her in London? How stupid her sister had been. He was a womanizer, she knew that only too well. He chased women, he had even chased her, his wife’s little sister.

And the duped and besotted Mary had poured more money into his hands for his real estate schemes in Spain. And without a second thought, led by something other than her brain. That urgent itch between her legs … driving sexual desire … how it blinded a woman.

Well, she knew all about that, didn’t she? The image of that hunk of a man Tom Selmere was still there somewhere in her head even after ten years. Another man on the make, lusting after his new wife’s stepdaughter, and a fifteen-year-old at that. Married to Harry’s widow Catherine before Harry was barely cold in his grave. And wanting to get Harry’s daughter into his bed as well. Hadn’t the widow woman been enough to satisfy the randy Tom? She had often wondered about that over the years.

Philip Alvarez was cut from the same cloth.

What the hell had Philip done with all that money? Seventy-five million. Oh God, so much money lost … our money … Deravenels’ money. He had seemingly never really accounted for it. Would he ever? Could he?

We will make him do so. We have to do so. Surely there was documentation? Somewhere. Mary wouldn’t have been that stupid. Or would she?

My sister’s management of Deravenels has been abysmal. I have long known that from my close friends inside the company, and Cecil had his own network, his own spies. He knows a lot more than he’s telling me; trying to protect me, as always. I trust my Cecil, I trust him implicitly. He’s devoted, and an honourable man. True Blue. So quiet and unassuming, steady as a rock, and the most honest man I know. Together we’ll run Deravenels. And we’ll run it into the black.

Rising, Elizabeth left the dressing table, moved towards the door. As she did so her eyes fell on the photograph on the chest. It was a photograph of her and Mary on the terrace here at Ravenscar. She’d forgotten it was there. Picking it up, she gazed at it. Two decades fell away, and she was on that terrace again … five years old, so young, so innocent, so unsuspecting of her treacherous half-sister.

‘Go on, Elizabeth, go to him. Father’s been asking for you,’ Mary said, pushing her forward.

Elizabeth looked up at the twenty-two-year-old, and asked, ‘Are you sure he wants to see me?’

Mary looked down at the red-headed child who irritated her. ‘Yes, he does. Go on, go on.’

Elizabeth ran forward down the terrace, ‘Here I am, Father,’ she called as she drew nearer to the table where he was sitting reading the morning papers.

He lifted his head swiftly, and jumped up. ‘What are you doing here? Making all this noise? Disturbing me?’

Elizabeth stopped dead in her tracks, gaping at him. She began to tremble.

He took a step towards her, his anger apparent. He stared down at her, and his eyes turned to blue ice. ‘You shouldn’t be on this terrace, in fact you shouldn’t be here at all.’

‘But Mary told me to come,’ she whispered, her lower lip trembling.

‘To hell with Mary and what she said, and I’m not your father, do you hear? Since your mother is dead, you are … nobody’s child. You are nobody.’ He stepped closer, shooing her away with his big hands.

Elizabeth turned and ran, fleeing down the terrace.

Harry Turner strode on behind her, followed her into the Long Hall, shouting, ‘Nanny! Nanny! Where are you?’

Avis Paisley appeared as if from nowhere, her face turning white when she saw the bewildered and terrified child running towards her, tears streaming down her face. Hurrying forward, Avis grabbed her tightly, held her close to her body protectively.

‘Pack up and go to Kent, Nanny. Today,’ Harry Turner told her in a fierce voice, glaring at her.

‘To Waverley Court, Mr Turner?’

‘No, to Stonehurst Farm. I shall telephone my aunt, Mrs Grace Rose Morran, and tell her you are arriving tonight.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Without another word Avis led Elizabeth towards the staircase, cursing Harry Turner under her breath. What a monster he was. He punished the child because of the mother. She loathed him.

Elizabeth looked at the photograph again, and then threw it into the wastepaper basket. Good riddance to bad rubbish, she thought, as she left the bedroom.

THREE

Elizabeth ran down the wide staircase and crossed the Long Hall, then she paused, listening. She could hear male voices in the nearby library, and hurried there at once. She pushed open the door and went in, and immediately came to a stop, taken by surprise.

Having expected to see Nicholas Throckman, she was startled by the sight of Robert Dunley. Her childhood friend, whom she had known since they were both eight years old, was standing with Cecil near the window. The two men were deep in conversation and oblivious to her arrival.

But as if he sensed her sudden presence, Robert unexpectedly swung around. Instantly his face lit up. ‘Good morning, Elizabeth!’ he said, as he strode towards her.

‘Robin! I didn’t expect to see you here!’

‘You know I always turn up like the proverbial bad penny.’ He grinned as he swept her into his arms and hugged her to him. He released her, kissed her cheek, and explained, ‘When I spoke to Cecil earlier, I asked him not to tell you I was coming. I wanted to surprise you.’

‘Well, you certainly did that,’ she exclaimed, laughing with him. Tucking her arm through his, the two of them joined Cecil.

Elizabeth was glad Robin was here; he had always been her devoted friend, and she still remembered the nice things he had done for her when she was in disfavour with her sister. She never forgot that kind of gesture. Dear Robin, so special to her.

Cecil, staring at her through those clear, light-grey eyes of his, said in a quiet voice, ‘Only a bit of minor deception on my part, Elizabeth.’

‘I know,’ she answered, smiling at him.

‘Would you like a glass of champagne? Or something else perhaps?’ Cecil asked, walking over to the drinks cart.

‘The champagne, please.’ Letting go of Robert’s arm, Elizabeth stationed herself in front of the window, gazing out at the panoramic view of the North Sea and the cream-coloured cliffs that stretched endlessly for miles, all the way to Robin Hood’s Bay and beyond.

What a breathtaking view it was, and most especially today. The sun was brilliant, the sky the perfect blue of a glorious summer’s day, and, in turn, the sea itself looked less threatening and grim, reflecting the sky the way it did. This view had always thrilled her.

‘It looks like a pretty spring day out there,’ Robert murmured, coming to stand next to her. ‘But it’s an illusion.’

‘Oh, I know that.’ She eyed him knowingly. ‘Like so much else in life …’

He made no response, and a moment later Cecil handed her the flute of champagne. She thanked him, sat down, and looking at both men, said, ‘I wonder what has happened to Nicholas? Shouldn’t he be here by now? It’s almost one.’

‘I feel certain he’ll arrive at any moment,’ Cecil reassured her. He glanced at Robert, raised a brow and asked, ‘How was the traffic?’

‘Not too bad. But Nicholas might be a bit more cautious than I am. I’m lucky I didn’t get stopped by a traffic cop. I drove like a fiend.’

‘Nicholas is bringing me the black box,’ Elizabeth announced, looking at Robert. But before he could respond, she changed the subject abruptly. ‘If I’m not mistaken, you were rather friendly with Philip Alvarez, weren’t you? Didn’t you go to Spain with him a while ago?’

Robert nodded. ‘Yes. But I can’t say I was very friendly with him. Let’s put it this way – he was always pleasant to me, and at one moment he needed advice, mostly from my brother Ambrose. Actually, we went to Spain together, to do a small job for him.’

Elizabeth opened her mouth to say something and instantly closed it when she saw the warning look on Cecil’s face.

Cecil cleared his throat. ‘I don’t think we ought to get into a long discussion about Philip Alvarez at this particular moment. Robert, you might be able to shed some light on that resort he was building in Spain, so do let’s plan to have a little talk. Later. I think Nicholas has just arrived.’ Rising, Cecil walked out into the Long Hall, said over his shoulder, ‘Yes, it’s him.’

A second later, Nicholas Throckman was greeting Cecil, Elizabeth and Robert, a wide smile on his face. They were all old friends, and enjoyed being together. After accepting a glass of champagne, and raising his glass to them, Nicholas said, ‘I’m so sorry to deliver this in such an unconventional fashion, Elizabeth.’ He chuckled. ‘In a Fortnum and Mason shopping bag, of all things. But actually, this is how it came to me. Anyway, here it is.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with a Fortnum and Mason shopping bag,’ Elizabeth replied as she took it from him. Placing it on the floor next to her, she lifted out the black box; holding it in both hands, she stared down at it and felt a shiver run through her. The box was, in fact, more like a jewel case, and embossed across the lid in now-faded gold letters was the name she revered: Edward Deravenel.

Placing it on her knee, with her hands on top of it, she said slowly, it in a shaky voice, ‘When I was eleven, two years after my father had accepted me as his daughter again, he showed me this box. And he told me a story about it. Or rather, about what’s inside. Come and sit down for a minute or two. I’d like you to hear what Harry Turner told me fourteen years ago.’

The three men did as she asked, nursing their glasses of champagne. All were curious, wanted to hear the story.

Elizabeth did not immediately begin. Instead she looked down at the box once more, smoothed her hand over it, seemed suddenly thoughtful, far away, lost in memories.

Robert Dunley, watching her intently, could not help thinking how beautiful her hands were, long and slender with tapering fingers and perfect nails. He had half-forgotten her lovely hands …

For his part, Nicholas was admiring her gumption and disregard for convention. Here she was, wearing a bright red sweater and matching trousers on the day her sister had died, and she didn’t give a damn what any of them thought. But that was Elizabeth, honest to the core. He knew, only too well, that there had been no love lost between the sisters, and he admired Elizabeth for not pretending otherwise.

Cecil’s thoughts were on Elizabeth’s quick, keen mind, the way she had mentioned Philip, quizzed Robert about the trip to Spain. Dunley might well be a good source of information about the disastrous investment Mary had made … he would talk to him later.

Elizabeth shifted her position on the sofa, glanced up at the painting which had hung above the fireplace here in this library for seventy years or more … The life-size portrait of Edward Deravenel … what a handsome man he had been: her father had truly looked like him, and so did she.

Focusing on the three men, she said, ‘This box once belonged to him, my father’s grandfather, as you all know.’ She gestured to the portrait, then, lifting the lid off the box, she took out a gold medallion on a slender chain and held it up for them to see. It glinted in the sunlight.

On one side was the Deravenel family emblem of the white rose and fetterlock, the rose enamelled white; on the other side of the medallion was the sun in splendour, commemorating the day Edward had taken the company away from the Grants of Lancashire in 1904. Around the edge of the medallion, on the side bearing the rose, was engraved the Deravenel family motto: Fidelity unto eternity.

‘I’m aware you’ve all seen this medallion before, as have I. But my father first showed it to me when I was eleven years old, as I just told you. He explained that his grandfather had designed it, and had had six of them made. For himself, his two cousins, Neville and Johnny Watkins, his best friend Will Hasling, and two colleagues, Alfredo Oliveri and Amos Finnister. They were the men who had helped him take control of the company, and were devoted to him for the rest of his life. Father then went on to confide that his mother, Bess Deravenel, had actually given it to him when he was twelve … just before she died. Apparently, her father had asked her to keep it safe for her younger brother, who would one day inherit the company. Well, you know that old story about the two Deravenel boys disappearing in mysterious circumstances. My grandmother explained to Father that she had been keeping it for his elder brother Arthur, who had unexpectedly died when he was almost sixteen. And now she wanted Harry to have it, because he would become head of the company –’

‘Didn’t Bess ever give the medallion to her husband, Henry Turner?’ Robert asked, cutting in peremptorily.

‘Obviously not,’ Elizabeth answered. ‘Actually, now that I think about it, my father never mentioned his father in that conversation about the medallion, he just told me how thrilled he’d been to get it, and proud. He said he treasured it because of its historical significance. He adored his mother, and I suspect it was extra special to him because it was one of her last gifts to him.’

‘And now it’s yours,’ Nicholas said, gazing at her fondly, his eyes benign and caring. Like Cecil and Robert, he was extremely protective of her, and would always defend her and her interests.

Elizabeth went on, ‘My brother Edward received it after my father’s death, even though he was too young to run the company, as you all know. It was his by right. And then it went to Mary when Edward died. Whoever wears it is the head of Deravenels, but basically it is only a symbol. Still, it’s always been tremendously important to the Turners, and it’s passed on to the next heir immediately.’

Cecil said, ‘It’s a beautiful thing, and when your father wore it on special occasions he did so with great pride.’

She nodded. ‘Yes, he did. You know, there’s another bit of family lore attached to this particular medallion, which Father told me about. Seemingly, Neville Watkins and Edward Deravenel had a terrible falling out, a genuine rift that went on for years and was devastating to everyone.’ She took a sip of champagne, and continued, ‘Johnny, Neville’s brother, was torn between the two of them, and tried to broker a rapprochement, but couldn’t. Ultimately, he had to take his brother’s side, he had no choice. When he was killed in a car crash in 1914 he was wearing the medallion under his shirt. Edward’s brother Richard brought Johnny’s medallion to him, and Edward wore it for the rest of his life. His own he gave to his brother.’

Now picking up the medallion again, leaning forward, Elizabeth showed them the side bearing the image of the sun in splendour. ‘If you look closely, you can see the initials J.W. which apparently Edward had engraved on the rim here, then he added his own initials. When my father received the medallion, he added his initials, as did Edward, and also Mary.’ She passed the medallion to Cecil, who looked at it closely then gave it to Nicholas, who did the same and handed it to Robert.

After staring at the series of initials, Robert glanced at her, and announced, ‘You must wear it today, Elizabeth. Now. Because it’s yours and it signifies so much, the history of your family. Next week I’ll have your initials added to the rim, if that’s all right with you?’

‘Why that’s lovely of you. Thank you, Robin.’

Rising, he went over to her, opened the clasp and fastened the gold chain around her neck. ‘There you are,’ he said, smiling down at her. ‘You’re now the boss!’

Before she could say anything, Lucas appeared in the doorway of the library. ‘Lunch is served, Miss Turner,’ he announced.

‘Thank you, Lucas, we’ll be right in.’

Jumping up, Elizabeth hugged Robert, and said softly against his ear, ‘You always manage to do the right thing, ever since we were little.’

‘And I can say the same thing about you,’ he answered, taking her arm and leading her out of the library into the Long Hall, followed by Cecil and Nicholas.

Once they were in the dining room, Elizabeth turned to Cecil, and said, ‘Come and sit next to me, and Nicholas, Robin, please sit opposite.’

They all took their seats, and Elizabeth said, ‘We’re having Yorkshire pudding first, then leg of lamb, roast potatoes and the usual vegetables. I hope you’re going to enjoy it.’

Nicholas grinned. ‘A traditional Sunday lunch is my favourite meal of the week. I’ve been looking forward to it all morning.’

‘I bet you didn’t get many of those in Paris, did you, old chap?’ Cecil said. ‘And by the way, I for one am glad you’re back.’

‘So am I,’ Nicholas asserted. ‘And from what I’ve gathered from our phone conversations, there’s a lot for us to do.’

Cecil nodded. ‘That’s true, but before we start reorganizing the company, and getting it on a more profitable level, I think we have to do something about the board. It’s top heavy.’