Полная версия

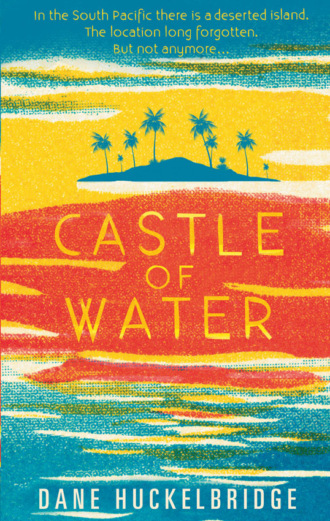

Castle of Water

DANE HUCKELBRIDGE was born and raised in the American Middle West. He holds a degree from Princeton University, and his fiction and essays have appeared in a variety of journals, including Tin House, The New Delta Review, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic. Castle of Water is his first novel, although he has also authored two historical works on American whiskey and beer, respectively. He lives with his wife in Paris, France, and New York City.

To you, my love, my Piment d’Espelette.

Thank you.

The cyclone ends. The sun returns; the lofty

coconut trees lift up their plumes again; man

does likewise. The great anguish is over; joy

has returned; the sea smiles like a child.

—PAUL GAUGUIN

Moi je t’off rirai des perles de pluie

Venues de pays où il ne pleut pas.

Je creuserai la terre jusqu’après ma mort

Pour couvrir ton corps d’or et de lumière.

—JACQUES BREL

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Two

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Part Three

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Acknowledgements

Copyright

PART ONE

1

The flat is in the tenth arrondissement of Paris, on a derelict street called Château d’Eau. To find it is simple: Just take a right at the arch, go down rue Saint-Denis, steer clear of the dog shit, and you cannot miss it. To find beauty in it, however, is a bit more daunting. The charms of the alley do exist, if one squints past the worn-out tabacs and disheveled filles de joie that ply their trades along its curbs. Fortunately, the man who lives there is accustomed to squinting and proud to call the place his home.

He wakes earlier than usual on this particular morning. He does not rise immediately but lies awake for a moment, savoring the stillness of the chill blue hour. Then, at last, he decides to get up. A splash of water on the face, a quick brushing of teeth, a puckering spit, and a satisfied gargle. He smiles at his scarred and bearded reflection—grayer, it seems, with each passing day.

Ablutions complete, it’s time to get dressed. First he slips on an old moth-hounded sweater, followed by corduroy trousers flecked with white paint. A Harris Tweed jacket is pulled from the closet, the elbows of which are worn down to fuzz. Oh, and shoes—can’t forget those. The man puts on argyle socks and scuffed leather brogans and tiptoes out of his bedroom door. He considers briefly leaving a note in the kitchen but doubts he’ll be gone long enough to even be missed. He does, however, pause at the end of the hallway, to press his ear to another door and give it a listen. Satisfied with the silence, he leaves the flat, padding delicately down the winding stairs, past the dim halos of hall lights conferred upon wallpaper, only to realize halfway down that he’s forgotten yet again to put in his contacts. Damnit. He trundles back up and plops them in without so much as a glimpse in the mirror. Then he leaves.

The man decides to have breakfast at a café in the neighborhood, and he sits outside despite the chill. Huddled in his chair, fingers laced around his coffee, he watches the city yawn back to life. The rising sun scrubs the indigo out of the air; the streets for once smell washed and clean. Shopkeepers are slowly raising their shutters, starch-crisp waiters are unstacking their chairs. Even the femmes de la nuit have called it a night. It’s all part of a timeless ritual, one of which he never tires.

The man finishes only one of his two tartines, perhaps because he is not very hungry, possibly because of something more. The untouched piece of toast is wrapped in a napkin and pocketed away for general safekeeping. He pays the waiter, slurps back the last of his coffee, and heads next door to a Turkish grocer. The door chimes and he vanishes inside, only to reemerge seconds later with a paper bag tucked under his arm. With his free hand he hails a taxi and asks to be taken to Père Lachaise.

The driver is a friendly West African named Noël. The melodies of his homeland pulse quietly through the radio. The man likes the music and asks the driver where it is from. Senegal, the driver says. The man settles back into his seat, absorbing the rhythms and enjoying the ride. He gazes out at the fountains etched in verdigris, and the monuments steeped in history, and the streets lined with cracked cobblestones. He clutches his paper bag both tightly and tenderly, as if it is a precious thing that someone might take. He closes his eyes and lets the light bleed through his eyelids, as marimbas hint at warmer climes.

The sun is still low but fully risen when the man arrives at the gates of Père Lachaise—which are, incidentally, in the process of being opened by a jumpsuited groundskeeper lame in one leg. Bonjour, Claude, the man says to the groundskeeper. Bonjour, monsieur, the groundskeeper replies. Also waiting beside the entrance is a quartet of American art students, smoking cigarettes and laughing to themselves. Unlike the man with the paper bag, they are young and have been up all night. In a burst of drunken enthusiasm, they decided to pay the famous cemetery a visit.

One of the Americans thinks he recognizes the man with the paper bag—he looks very familiar. The boy’s eyes bulge, the beard and the scars. Holy shit, he whispers, his unlit Lucky Strike tumbling from his lips. Is that who I think it is? His friends cast glances over their hunched shoulders. It is. To think, they came to see a dead rock star and instead happened upon a living legend. They titter among themselves, giddy just to be standing so close. They know he lives in Paris. And they’ve certainly heard all the stories. Should they follow him in? The groundskeeper stands aside and the man with the paper bag enters. They should, and they do.

The man with the paper bag does not notice them, however. His mind is on other things. He walks with serene intent through the inordinate quietude and beauty of the place, a monument to France itself. The fading names above the crypts are soft as feathers when uttered upon the lips—which he does, without a breath, with hardly a sound, the downy purr of double r’s, the agile sweep of accents aigus.

His path takes him beneath a wicker of frosted elm trees, down a brief and chestnut-scattered embankment, to a cluster of old family plots on the cemetery’s edge. He goes delicately but with purpose—he knows the way, he is intimate with these surroundings. The American students trail behind by a respectful distance. They are curious but have no wish to disturb him. Wait until we tell our friends back home, they say, the insatiable lot of them murmuring as one.

The man stops at last in front of a grave, newer and less faded than the rest. The moss has yet to even stake its claim. The students hold back; they suddenly feel guilty, unintentionally intrusive. But they know they can’t turn away. They look on as the object of their curiosity kneels before the grave. His head is bowed, and his hands are resting upon the headstone. He seems to be speaking—but what is he saying? They can’t make out a single word. Whatever it is, it goes on for some time, until at last, his vigil concluded, the man wipes his eyes and rises to his feet. He takes something from the paper bag, something thick and clustered—what, they’re not certain—and sets it down upon the grave. Then he turns and walks away.

The students wait until he is well out of sight before they dare approach. They are flabbergasted by what they have seen. Whose grave is this, anyway? they wonder aloud. And, like, what kind of flowers were those, exactly? They gather about the headstone in the cold morning light, the four of them shivering and goosefleshed and dying to know.

The marble is inscribed with a name they don’t recognize—it sounds French, but they’ve never seen it before. And as if that weren’t enough, the flowers the man left behind are not flowers at all. Instead, resting atop the grass and loam and dried husks of chestnuts is something bizarre, something out of place, something that they can neither understand nor believe.

A single bunch of green bananas.

The American students shake their heads and relight their cigarettes. They purse their lips and exhale in wonder. What exactly just happened? one of them asks, a girl in blue jeans and artfully trimmed bangs. I mean, like, do you think the stories are true? I have no idea, another answers, scuffing the cobblestones with his canvas sneaker. But it beats the hell out of Jim Morrison any day. And I’m, like, totally starving. Anybody want to go get breakfast?

They all do. And they count the crumpled remainder of the night’s euros to make sure they have enough, and they leave the bananas behind for the departed to keep.

2

At the first sputter of the engine and hint of a downward pitch, Barry Bleecker had uttered a prayer. He had prayed for a miracle. And a miracle was precisely what he received, although perhaps not one as helpful as he had hoped. For despite his entreaties to God, Buddha, Allah, and Vishnu, the engine did not kick back to life, the little Cessna 208 Caravan did not cease its dive, and no, he was not spared the soul-wrenching impact. The screams, the weeping, the bracing for death—all of that went on as fate had planned. But Barry, still semiconscious amid the floating debris and flaming oil, was spared his contact lenses and a single bottle of saline solution—neither of which seemed particularly miraculous, drifting by in a sealed Ziploc baggy at that dark and desperate moment. He almost forgot to gather them up, preoccupied as he was with staying afloat and expelling the salt water from his lungs. But gather them he did, perhaps compelled by the hint of buoyancy that the baggy provided. He tucked it up under his shirt, moaned once more toward the god(s) he assumed had forsaken him, and pushed off from the smoking hunk of fuselage to which he had been clinging barnacle tight . . . from the blue haze of the horizon, a fringe of palm beckoned.

The promise of firm ground proved more elusive than Barry had thought. The swim felt interminable, and in the dips between swells, when he lost sight of his destination, he nearly gave up hope. But the pure, reptilian desire to prevail goaded him on. His leaden arms kept paddling, his wooden legs never ceased to kick. When his body was finally washed up, dragged back, and then washed up again onto the sand, he wept like a baby, rolling onto his back, roaring with grief, although for what he did not know. Once that wellspring of emotion ran itself dry, he sat up, blinked, and looked at his surroundings. Or at least attempted to look—what met his eyes was a myopic blur. At some point—possibly in the crash, but more likely during his ordeal in the water—Barry Bleecker had lost both of his contact lenses. A loss of vision that could easily lead to a loss of life for a horribly nearsighted man stranded on a desert island 2,359 miles from Hawaii, 4,622 miles from Chile, and 533 miles from the nearest living soul. And at that moment, on the palm-lined rim of an uninhabited South Pacific atoll, Barry Bleecker was just such a fellow. Or almost such a fellow. For no sooner had he realized his predicament than he remembered the Ziploc baggy, which by then had tumbled from beneath his sopping Charles Tyrwhitt dress shirt and settled atop the soggy crotch of his Brooks Brothers slacks. At which point Mr. Bleecker, nerves and clothing equally frayed, laughed hysterically. A miracle, after all.

Barry dragged himself a few yards to drier ground, whisked the sand from his fingers, and peeled open the precious plastic bag. The foil top of the first contact lens package (there were six packages, which meant three pairs) was stubborn but gave. He set one on the tip of his index finger and examined it like the precious jewel that it was. Then, after a quick and cleansing splash with the saline solution, he plunked it into his eye. Hallelujah! What had been an inscrutable haze transformed with a blink into a vivid seascape. With a pirate’s one-eyed squint, Barry took stock of the foam-wreathed shoreline, the waltzing fronds, and the dappling of cirrus clouds that crawled across an otherwise impeccably blue sky (the storm that downed them having by that point passed). It was midday, and the sun was high. Quickly, he inserted the other contact as well and took to absorbing his new environs in their full three-dimensional splendor. On rubbery legs he executed his first tottering steps, calling out for help as he explored the beach. He walked for some time, shouting through cupped hands and listening through cupped ears, with waves and rustling the only response. And then his heart leapt—up ahead, a set of footprints in the sand. A tart joy overtook Barry as he raced forward, nearly tripping over the tattered cuffs of his slacks. Footprints! It could only mean . . . And then he stopped in his tracks. Literally his tracks. The footprints were his own. He had circled the entire island, and he was suddenly horrified by both his loneliness and its tininess. Circumnavigating the thing had taken less than ten minutes. And Barry wept, not for the first time on that diminutive island and certainly not for the last.

The arrival of night brought Barry little solace. The screams of tree frogs and the pitched chatter of insects, yes, but no solace. Crouched and shivering in a crude bower of palm fronds, surrounded by darkness, he reached instinctively to his pocket for a cigarette, only to dump out their mashed remains. In doing so, however, he remembered the plastic Bic that was tucked in the cellophane. And that, unlike his Parliament Lights, was still serviceable—he flicked at the flint and summoned a flame. And an idea came to him: a signal fire. Surely rescue planes would be out combing the waves. They would likely even pass over the island in their search for survivors. Barry struggled to his feet, again tripping over his tattered cuffs, and began gathering the driest palm fronds he could. After several trips to the beachhead, he had a rather impressive pile and, after a few dabs of his lighter, a convincing flame. He stood beside it, watching and waiting, certain the spotlights of some chopper or seaplane would come blazing from the murk. When they didn’t, and the fire burned down to embers, he scurried for more fronds to resuscitate it—an exercise that proved less than fruitful. Halfway into his second armful, it began to rain. Not a demure tropical sprinkle, but an honest-to-goodness downpour. Barry hurried back to his palm bower and huddled beneath its meager shelter. At some point, exhausted, he curled up to sleep, but on the cusp of obtaining it, he realized he had forgotten to take out his contacts. Crap. With exquisite tenderness, he removed each from its respective eye and deposited it carefully into its respective holder. He placed the plastic case in his pocket, beside the suddenly priceless Bic, and finally, blanketed by chill rains, lulled by the high whine of midges, he fell headfirst into a cavernous slumber.

3

Barry awoke to a parched throat, sore muscles, a mild sunburn, and the sickening realization of the predicament he was in. But first things first. Water, and then food. He had swallowed a considerable amount of ocean the previous day, and his last meal had been a granola bar consumed at the airport in Tahiti. Slowly, achingly, he crawled from beneath his little teepee of palm fronds and rose to his feet. He cracked his neck and squinted into the sunlight; it was overcast, but still bright. The waves rolled in, steadily, incessantly. The air tasted faintly of brine.

After a quick and unsettling bathroom break (the darkness of his urine was a disturbing reminder of his dehydration), he put in his contact lenses and turned for the first time away from the sea, toward the little island’s bosky heart. And bosky it was. Columns of trunks propped up an ever-shifting ceiling of frond leaves, through which fugitive slats of sunlight escaped. He stepped gingerly over the prickly undergrowth, as he had lost both his loafers the day before. The terrain became increasingly rocky the farther in he ventured, until he came to the base of a mountain or, perhaps more accurately, very steep hill. Boulders, bedded with some form of ferny moss, rose to a peak some five or six stories overhead. And nested snugly in their crevices were birds: gulls or terns or cormorants. Barry didn’t know, but they were living creatures sharing in his fate. And even more important, he found water. Two separate rock pools, both about the size of Jacuzzis, were coolly waiting, filled to the brim with the previous night’s rain. Barry inspected the pools first before consuming their contents. They both looked clean enough—one had a few odd squigglies jetting about its edge, some larvae, perhaps, but nothing that screamed befoulment. Barry chose the slightly more pristine of the two and brought several handfuls of the water to his lips. Its flavor was fresh and deliciously minerally, not unlike a white wine he had once tasted while touring Napa Valley with his girlfriend—fine, ex-girlfriend—Ashley. Well, perhaps that was a slight exaggeration, but after all he’d been through, a gulp of clean, cold water was nothing to sneeze at.

Once his thirst was slaked, all that remained was for his appetite to be sated, and that came courtesy of the island’s banana trees. Somehow he had missed the bunches of green, starchy fruit, dangling just above head level. But upon noticing their presence, he also became aware of their prevalence. Good, thought Barry, chewing on his sixth banana and fully prepared to eat six more. Water and bananas. I shall want for neither hydration nor potassium. And he laughed at his little joke, which, anyone with experience in survival situations can tell you, is a promising sign. Attitude is everything, and those that turn negative can be just as ruinous as diseased streams and toxic berries.

With his most basic of needs addressed for the immediate present, Barry returned to his post on the shore, ripping off the lower half of his slacks as he did so. They were shreds anyway, and cutoffs seemed more appropriate to the conundrums of a castaway. His sleeves he rolled up past his elbows, then muttered, “What the hell,” and took his shirt off entirely, wrapping it around his head in a sort of improvised French Foreign Legion hat. He breached the tree line and scanned the horizon, having transformed in a few short minutes from a high-yield-bond salesman at Lehman Brothers into a passable Robinson Crusoe. “Shit,” he muttered to himself. “Goddamn.” And goddamn was right—no rescue boats sat poised on the horizon, and no choppers hovered above the unfurling waves. He kicked sand at the remnants of his signal fire and considered his options. If only his cigarettes weren’t mush—he was dying for a smoke. After some deliberation, he vetoed a signal fire for being too labor-intensive and decided instead to write a message in the sand. After some scouring (he was surprised at how little loose wood there was, but then again palm trees didn’t exactly have branches), he settled on a rock with a jagged edge. Using it, he carved out SOS as large as he could. He then repeated this in several other locations, doing another lap of the island. He considered again starting a fire, but the palms he found were too damp, and he ultimately gave up on the idea altogether. A school of ominous storm clouds was quietly gathering, squirting its dark squid ink deep into the horizon; finding shelter took precedence over everything else.

Barry thought for a few minutes, studying the tree line and hoping for an idea. After considerable grumbling, head-scratching, and additional sand kicking, he came to one palm that hung especially low, jutting out over the beach at a shallow angle. Yes, it was just close enough to the ground to do the trick and was sheltered quite well by the surrounding trees. Newly inspired, Barry set to work, harvesting the larger fronds he could find and leaning them in thick layers against both sides of its trunk. Within an hour, he had something resembling a tent. When the rains came later that evening—and boy, did they come—he was even able to stay relatively dry. It was a definite improvement over the leaf pile of his first night, which offered some relief to Barry, although not much. He was still stuck alone on an island not much bigger than Madison Square Park. Still uncertain if anyone was searching for him. Still at the mercy of a negligent sea and a vastly indifferent sky. And then of course there was the pilot and the other two passengers. Christ. Barry hadn’t even thought about them in that flaming mess of twisted steel and surging water. Had he seen them, he would have certainly tried to help, but he had not. Chances were, they hadn’t survived the crash. No, the Filipino pilot with the Hawaiian shirt was probably at the bottom of the sea, the young French honeymooners were likely food for fishes—a thought that alarmed and saddened Barry, but comforted him in a strange way, too. It alarmed him because they had all seemed like nice people, in no way deserving of their fate. But it also served as a reminder of the fact that there were far worse places he could be at that moment. Like the ocean floor, for example. He stifled a shudder and listened to the rain, damp, weary, very afraid, but also very much alive, and in that fact alone he found vast reassurance. “Crap,” he said out loud, once again on the edge of sleep. He’d forgotten yet again to take out his contacts.

4

Had Barry not plucked out his contacts, had he taken a midnight stroll instead around the island’s sandy perimeter before hitting the hay—or palm fronds, as it were—he would have come to discover just how mistaken he was about the other passengers. Or at the very least, one of them, anyway. For on the shore directly opposite his, a Day-Glo orange raft was slowly deflating. And curled fetally inside its rubbery womb was Sophie Ducel, exactly one-half of the French honeymoon duo that Barry had assumed to be joined for eternity underwater. Her eventual destination proved identical to Barry’s, but the manner of her arrival was markedly different.