Полная версия

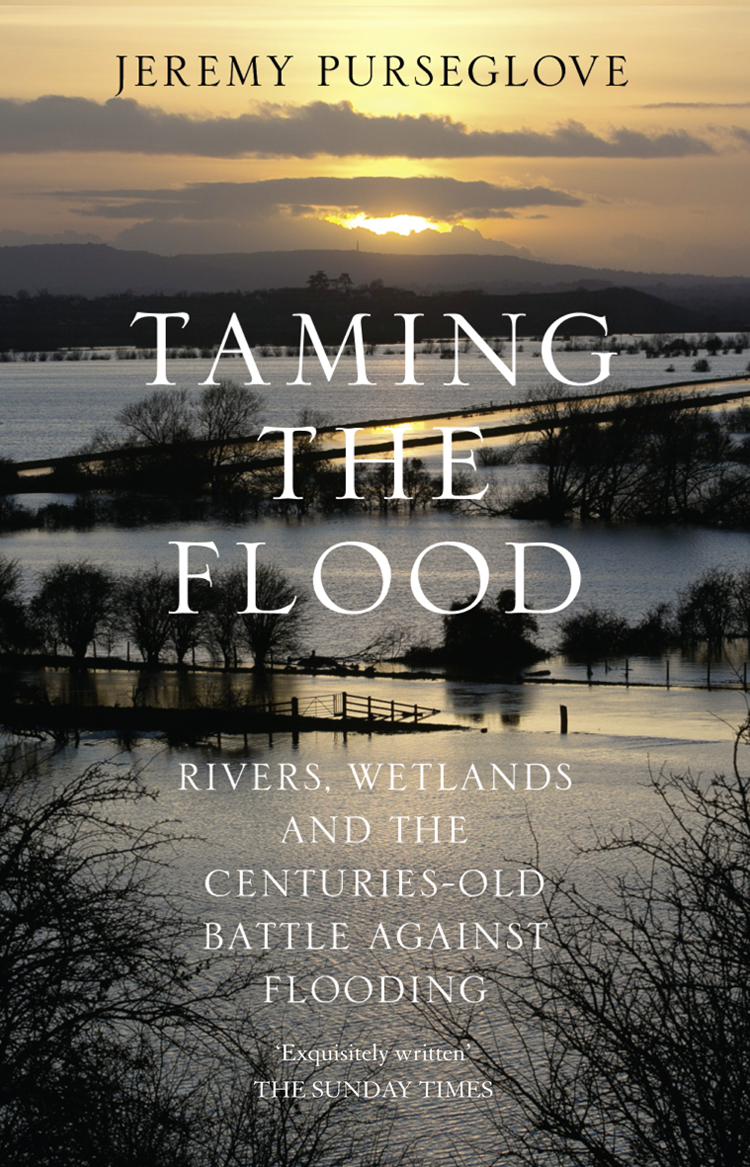

Taming the Flood: Rivers, Wetlands and the Centuries-Old Battle Against Flooding

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in the United Kingdom by Oxford University Press, 1988

This revised and updated second edition first published by William Collins in 2015

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2017

Text © Jeremy Purseglove 1988, 2015, 2017

Cover photograph showing sunset over the flooded Somerset Levels, February 2014 © Matt Cardy/Getty Images

Jeremy Purseglove asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008132217

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008132224

Version: 2017-03-08

Praise for Jeremy Purseglove:

‘Taming the Flood most deserves its status as a classic […] for its evocation of place […] the descriptions of wetlands are exquisitely written. This fine book calls for, and takes, a longer view.’

The Sunday Times

‘His original determination remains the driving force of this compelling book. Mr Purseglove’s mission was to show why rivers really matter to England and how our wetlands are a vital part of the natural scene. His descriptions are wonderfully accurate, his writing captivating and his enthusiasm catching. On any level, it’s a good read, but, as a call to action, it’s outstanding […] It is his love of the subject, his deep knowledge and poetic insight that wins us from the very first page.’

John Selwyn Gummer, Country Life magazine

‘Jeremy Purseglove has a gift that is increasingly rare in these days of scientific specialisation – of joining practical wisdom about working with nature and the land to an imaginative appreciation of their place in our history and culture.’

Richard Mabey

‘An authoritative history of British wetlands and the centuries-old battle to control them. It is a celebration – beautifully illustrated – of life in and around the water and it is an eloquent plea to water authorities, to farmers and to Government to respect that life.’

BBC Wildlife

‘Delightfully written and beautifully illustrated.’

Observer

‘A pioneering and counter-cultural work.’

Oliver Rackham

Dedication

To all those engineers, digger-drivers and farmers who are taking nature conservation seriously.

*

HOTSPUR. See how this river comes me cranking in,

And cuts me from the best of all my land

A huge half-moon, a monstrous cantle out.

I’ll have the current in this place damm’d up,

And here the smug and silver Trent shall run

In a new channel, fair and evenly;

It shall not wind with such a deep indent

To rob me of so rich a bottom here.

GLENDOWER. Not wind! It shall, it must; you see it doth.

SHAKESPEARE, I Henry IV, III. i.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION

PREFACE

1. River versus Drain: The Conflict within Traditional Flood Management

2. The Fear of the Flood: Traditional Attitudes to Wetlands

3. The Winning of the Waters: A History of the Fight against Flooding until the Post-War Era

4. The Wasting of the Waters: The Real Cost of Orthodox River Management

5. Riverside Riches: The Need for Management on Wet Land and some Alternative Economic Uses

6. Civilizing the Rivers: The New Approach to River Management

7. Creative Flow: Rules for Good Practice in River Management

8. The Last-Ditch Stand: The Wetlands Debate, 1974–1988

9. The Flood Untamed: Rivers and Wetlands, 1988–2017

PICTURE SECTION

FOOTNOTES

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THIS BOOK

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PREFACE

Taming the Flood, first written in 1986, was long accepted as a standard work on the conflicts between flood alleviation and nature conservation in England and Wales and how to manage rivers in an integrated way. It finally went out of print and then it rained. It rained a lot. Large areas of the country went under water. Floods and all the dilemmas and controversies that come with them are back on the agenda. For these reasons it seems very timely to revise and update this book. In an additional final chapter I have examined the latest twists and turns in these issues leading to 2016.

Between 1977 and 1989, as one of the first environmentalists in the British water industry, I was employed by the Severn Trent Water Authority and, as it became later, the National Rivers Authority. One of the prime duties of this organization was to reduce flooding. This led it into regular conflict with nature conservation, which it was my duty to defend. I therefore found myself in the middle of a long-standing environmental debate concerning river and wetland management, which in the 1980s became increasingly controversial and under the national spotlight. This debate led to major reforms and initiatives whereby landowners were paid compensation to maintain important habitats on their land. Higher environmental standards were also set for river management, and the old world of farmer-dominated land drainage began to evolve to the more rounded system of modern flood defence that we know today. These changes were recorded in chapter 8, which concluded the original book.

Taming the Flood was published on the eve of water privatization, which appeared to bring in a new age of responsible river and wetland management under what is now the Environment Agency. The issues and conflicts that I described seemed to settle down. But they did not go away. With the onset of climate change over the past decade and especially during the winters of 2013–2014 and 2015–2016, the floods have returned with a vengeance. The old issues and conflicts recounted in these pages have resurfaced with an even greater urgency as the dredging debate over how to deal with unprecedented flooding is back in the national media.

In revising the book I have realized that it is both impossible and inappropriate entirely to rewrite the first eight chapters. They belong to the period in which they were written. As such, they must largely remain. Some passages may now seem outdated by the march of history and the benefit of hindsight, particularly with subsequent reforms to both administration of flood defence and the Internal Drainage Boards. Whenever possible, I have appended footnotes at the bottom of the page so that the reader can discover the subsequent developments that have affected particular wetlands or issues under discussion. The original book now reads as a chronicle that hugely informs the events from 1989 to 2016, which are covered in a new chapter 9.

It could be argued that, without reading those earlier pages, it is impossible properly to understand the current debate. This was a passionately campaigning book when I first wrote it, but I have found that, revisiting the current issues after 25 years, rivers and wetlands are still in desperate need of a passionate campaign. Back in the 1980s the big new idea was that the machines that dredged and straightened rivers could also be used to enhance their habitats as part of the normal duties of reducing flooding. Now, the big new idea is that we can use the whole landscape to absorb much of the rain before it reaches the rivers. In this way we can also restore many of our damaged landscapes, especially the most intensive farmland. It remains to be seen whether in this latest crisis of climate change we will rise to the challenge.

CHAPTER 1

RIVER VERSUS DRAIN

The Conflict within Traditional Flood Management

I never thought for one moment that my life would become bound up with rivers. It all began when a woman threatened to tie herself to a willow tree. I had just started working as a landscape architect for a water authority, and my duties were to involve planting trees around reservoirs and new office buildings. I had never heard of river engineers until one morning a very harassed engineer rang to ask me to persuade the woman in question not to tie herself to the ancient pollard, which he intended to fell. Indeed, he asked me, as the authority’s environmentalist, to suggest ways of calming the local community’s very vocal outrage at what he was intending to do to their river. The engineer explained his problem. All he was attempting to do was to prevent the river from flooding these ungrateful people’s houses. For this, however, many trees would have to be removed, and the river would have to be deepened and straightened. It would cease to be recognizable as the river that the local people enjoyed, but it would become a very efficient drain, so that their sitting-rooms would no longer be ruined periodically, and farmers with land adjacent to the river would be able to grow more and better crops to feed the very people who were complaining. So the case was put: river versus drain.

This book is about that conflict of values, the efforts made to come to terms with that conflict, and its implication for one of the major issues of our time—the reshaping of our farm policy, which, with the single aim of increased food production, has transformed the countryside in what is perhaps the greatest agricultural revolution since the settling of England began.fn1

Seldom has the conflict over what a river means to different people been more dramatically highlighted than in the case of the river Stour at Flatford Mill. Here John Constable painted The Hay Wain. Reproduced in calendars, on birthday cards, and in coffee-table books, this painting has become almost a ritualized symbol of the reverence that English people have for their countryside. I remember once dealing with a particularly brutal river scheme, and seeing hanging in the engineers’ portacabin, which overlooked the now canalized river, a calendar showing The Hay Wain. The connection was not made. In 1984 the Anglian Water Authority applied for permission to carry out a land-drainage scheme on the Stour between Stratford St Mary and Flatford Mill, with the purpose of converting the riverside pasture to oil-seed rape. Mr John Constable, the painter’s great great grandson, protested in The Times: ‘Believe me, rape is what we’re talking about.’ The water authority responded with its case: ‘We are up against a lot of pressure from landowners to do something about the flooding.’1

A river is a symbol of changeless change. Overnight, in a flash flood, it will dramatically move its banks, depositing shoals and cutting new channels. In recent decades, the Severn has been steadily undercutting the riverside churchyard at Newnham. The skeletons of the village forefathers are regularly exposed and then claimed by the river, and now the church itself is threatened. The local diocese has appealed to the water authority to do something about it; but something as elemental as the ever-moving Severn is beyond the resources of even the richest and most powerful water authority. At Crowland in Lincolnshire stands a medieval bridge, stranded high and dry in the middle of the town. The three streams which once ran beneath it have long since vanished, but, at the back of the town, the water still finds its way to the sea, as it has from the beginning of time. William Wordsworth described the river Duddon as something that would always be recognized by succeeding generations:

I see what was, and is, and will abide

Still glides the stream and shall for ever glide.2

Nowadays, however, we are capable of transforming rivers so that they become quite unrecognizable. If, while waiting in the rush-hour queue at Sloane Square tube station, you chance to look up, you will see a large iron pipe. It is, or was, the river Westbourne. This is the ultimate in human domination of a river, although many city rivers might just as well be piped. The Rea in Birmingham and the Medlockfn2 in Manchester hurry down through their straitjackets of steel and concrete, unnoticed by the passing crowds.

WILDLIFE OF RIVERS

The endurance of rivers, which is part of what makes them such a potent symbol in our culture, is also precisely the reason why they matter so much to ecologists and scientists. In this country there is probably no river or wetland which is ‘natural’ in the sense that it has never had human interference; but river systems have two major characteristics which have enabled their wildlife in all its original complexity to survive interference better than most other systems. First, their continuous, linear nature provides plants and animals with an opportunity to move up and down them. In the modern landscape, woods, ponds, and heaths, for example, are increasingly isolated within enormous fields of pasture or arable land; and the other major corridor for wildlife, the hedge system, has, of course, been cheaper and easier for farmers to remove than the river itself. Second, because a river’s nature is one of changeless change, forever on the move, the creatures that live in it have evolved strategies for surviving sudden floods and disruptions and alterations of the river’s course. Broken pieces of many water plants have the ability to root again; others have seeds that float or resist digestion in the stomachs of birds, and so can be transported upstream. River insects develop wings in the last stage of their life cycle, and dragonflies are known to be able to fly many miles. Indeed, some of our dragonflies regularly migrate across the North Sea. In June 1900 the air over Antwerp ‘appeared black’ with swarms of four-spotted chaser dragonflies, as they headed towards England.3 Fish instinctively fight their way upstream against the current, and many water birds and animals have the ability to travel long distances.

Other species are less mobile, and exist there simply because a river has always been there. In 1983 a hairy snail was discovered in the Thames marshes near Kew, where its ancestors had lived for the last 10,000 years. It is believed to be the last living relic of the days when these islands were joined to Europe and the Thames was a tributary of the Rhine, where the same species of snail is still found. Now, within two years of its discovery, the snail’s survival is threatened by a Thames Water Authority scheme.fn3

Of rather more popular appeal than hairy snails, perhaps, the dragonfly best represents the ancient life of the river bank, that point where land and water meet, where life began, and where waterside plants still provide a slipway up which dragonfly larvae climb to emerge in their full splendour every spring. In the liassic rocks of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire fossil dragonflies have been found which are not very different from those still hawking along the streams that cut their way through those same rocks on their way down to the Severn estuary and the sea.

The ultimate taming of a river. The river Westbourne flows in an iron pipe above the platform at Sloane Square underground station.

Over the millennia, creatures that live in the specialized conditions of rivers have evolved by adapting to these conditions. A babbling upland brook is physically very different from a lazy lowland river, and there are subtle gradations all the way between. These differences are further modified by the local geology, which affects the water chemistry, the local climate, and the particular conditions created by the dominant local plants. Thus a river’s wildlife is adapted to, and expresses, its particular local character and that of its different reaches with an almost infinite variety.

Dragonflies are a good example of this. There are upland dragonflies and lowland dragonflies. The Norfolk hawker (Aeshna isosceles) is confined to the Norfolk Broads, while the brilliant emerald (Somatochlora metallica) is a speciality of Surrey, Sussex, and Hampshire. The Beautiful Damsel (Agrion virgo) favours clear, gravel-bottomed streams, while the Banded Damsel (Agrion splendens), distinguished from the former by the blue-black bar on the male’s wing, is abundant on muddy-bottomed, less acid waters. Where they co-exist, the former tends to prefer the gravel, while the latter chooses the clay reaches. The damsels are among the great sights of the midsummer river bank, along which they flutter, enamelled with peacock blue and green; and it is entertaining to ‘read’ the physical conditions of a particular stream from the band on a damsel’s wing.

A single rock in a stream provides at least four habitats. Algae grow on surfaces that are always wet; the dry top supports lichens; mosses thrive on the wetted margins between the two; and many creatures hide in crevices under the rock. On many upland streams a large boulder will often be the chosen perching spot of the dipper.

Further down a river, common reed is a feature of many watersides. Thickets of fawn papery stems, tender green as they unfurl in the spring, have a specialized ecology all of their own. Even quite small stands may support a pair of reed buntings, while a larger reed bed provides a home for the reed warbler. The latter is often a favourite host for the uninvited cuckoo. Look closer into the reeds, and you will find a world within a world. The twin-spotted wainscot moth lays its eggs in the bur reed, but the larvae later transfer to the common reed as they fatten up and need a thicker stem to tunnel into. In the summer dusk the pale hatched moths float out over the riverside. A specialized fly, Lipara lucens, also tunnels into the reed stems, creating noticeable swellings known as cigar galls. Once the fly has flown, the empty gall provides a winter home for two other reed specialists: a bee, Hylaeus pectoralis, and a wasp, Passaloecus corniger, whose eggs will hatch in the following spring.

Few species have adapted so closely to their particular rivers as caddis flies, stoneflies, and mayflies, which, in their turn, have been cunningly imitated for bait by generations of anglers. In the larval stages, caddis flies build themselves cases out of the materials of the river bed. These provide them with camouflage and, depending on the speed of flow, either ballast or a means of transport. The faster the stream, the heavier the material chosen, while those species occupying slow-flowing rivers or ditches construct a case of wood around themselves to help them float to fresh feeding grounds.

The nymphs, or first larval stages of mayflies, are also adapted to very particular conditions. Some nymphs have specially shaped heads and legs, so that, when facing the current, they are pushed against stones into which they fit, and which save them from being washed away – certainly a case of going with the elements! The yellow may nymph is best adapted for rough boulders, while the marsh brown nymph fits against smooth stones, upon which its gill-like plates press down, thereby creating a vacuum. While some species are streamlined for fast flows, others are burrowers and bottom-crawlers. The claret dun nymph is at home in slow, peaty streams. It is peat-coloured, and its gills both camouflage it by breaking up its outline and enable it to breathe in still water. The blue-winged olive nymph lives among weeds such as water crowfoot. It is neatly shaped to lodge in close-packed vegetation, from which it can be in close contact with the fast-flowing oxygenated water it requires.

Reed buntings and common reed.

The culmination of all this unseen evolution on the river bed is one of the great phenomena of the English countryside, once seen, never forgotten. This is the day in the life of the mayfly. Very punctually in mid-May, the nymphs will rise from the bed of the river and hatch through a final nymph stage known to anglers as ‘duns’. Then, when the air is still, the elegant adults, the ‘spinners’, float upwards in their thousands and perform their mating dance. This is the sight that stays with even the casual observer. The gauzy tides of swarming males, waiting for the females, rise and fall as if on invisible yo-yos. Having mated, grey clouds of females glide to the water, lay their eggs, and die. With all the poignancy of a Shakespeare sonnet, it is over in the space of a summer day, until next spring.

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment.4

The life of a river has nothing to show more resonant of changeless change than the life cycle of the mayfly, a genus known even in the dry language of science as Ephemera.

Yet the return of the mayflies is no longer as inevitable as the return of May. They are steadily declining in many rivers, and have vanished from others. Pollution and the removal of riverside hedges have played their part; but above all, dredging and drainage have ironed out the varied bed conditions of gravel and silt to which the larvae of these and many other insects were so minutely adapted.

The otter, sliding up a river like a sleek cat and whistling to its mate under the moon, is truly king of the waters, and the presence of otters on a river system sets the final seal of well-being on its wildlife. The otter has captured popular imagination ever since the classics of Henry Williamson and Gavin Maxwell. It achieved tabloid status in April 1985, when it was on the front page of the Daily Mirror’s conservation shock issue; and, as a symbol of wildlife under threat, it is a sure money-maker for such causes as the World Wildlife Fund. The fact that people will give money to save the otter, a nocturnal animal whose presence is detected even by full-time otter survey teams only by its tracks and droppings, is the best answer I know to that mean-spirited and illogical argument: ‘What’s the use of saving it, if I can’t see it?’ It was enough simply to know that otters were out there somewhere. Alas, no longer. In 1977 leading conservationists produced a report showing that the otter had declined with disastrous suddenness.5 Whereas otters were present, even common, throughout the country in the 1950s, they are now abundant only in the extreme north-west of Scotland, leaving core populations in Wales and the West Country, and a dwindling interbred group of individuals in East Anglia. Hunting, disturbance, and pesticide residues had all played their part; but the major culprits were river boards and their successors which scoured the banks of undergrowth in which otters lay up during the day, and felled the mighty riverside trees, such as ash and sycamore, in whose buttress roots otters made their holts. Since 1977 otter hunting has been illegal, and the ban on the pesticide Dieldrin is starting to have a beneficial effect. But the many miles of treeless river inhibits recolonization by otters, and even in the 1980s there have been cases of water authority workers felling known otter holts.fn4