Полная версия

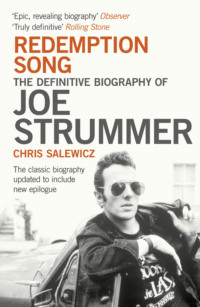

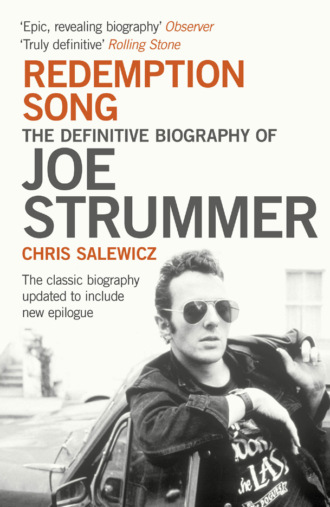

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

The bar is packed with people and a grey atmosphere of grief. I see Lucinda and hold her for a moment. Simultaneously she feels as frail as a feather and as strong as an oak beam. But she is clearly floating in trauma. I tell her how sorry I am, and as I speak my words feel inadequate and pathetic. From a stage at one end speakers are batting out reggae. The pair of pretty barmaids are struggling with the crush. I am handed a beer, which I down, pushed into a corner. I see a woman with a familiar face: Marcia, the wife of Jem Finer, effectively leader of The Pogues – I used to enjoy spending time with them at evenings and parties at Joe’s house when he still lived in Notting Hill. I am incredibly flattered by what she says to me. She says, ‘Joe always used to say that you were the only journalist he trusted. And he said he loved you as a friend. He really loved you.’ I am unbelievably touched by this. I want to talk to her more, but she is clearly looking for someone. I nearly burst into tears when what she has said fully registers with me. (I’m not unusual in being in such a state: all around me I see men putting their hands to their eyes, sobbing for a few moments.) Later Jem Finer, Marcia with him, deliberately seeks me out and tells me this again, both of them together this time.

Next to the cloakroom I find a couple more rooms, where food has been laid out. I grab a plate: smoked salmon, feta cheese salad, pasta – good nosh. And sitting down I find a middle-aged woman. The sister of Joe’s mum, and a great person, Sheena Yeats now lives in Leeds, where she teaches at the university. She’s very Scottish, however: ‘Well, this is the best funeral I’ve ever been to,’ she burrs, with a smile. ‘Joe would have really appreciated it.’ She tells me how Joe had been up to Scotland a month ago, to a wedding, and that he had been in touch with everyone in his family recently. She reminds me that Joe’s mum Anna had passed on in January 1987. ‘Although he chose to call himself Joe, because it was such an everyman name, his real name was John, a name with the common touch,’ she explains.

Bob Gruen tells me how Joe had been in New York a couple of months ago, in some bar, leading the assembled throng in revelry and having a great time. Seated nearby is Gerry Harrington, a Los Angeles agent who had guided Joe’s career when he was working on Walker and Mystery Train and releasing 1989’s Earthquake Weather. Joe had written a song for Johnny Cash last April, at Gerry’s house in LA, entitled ‘Long Shadow’: he plays it for me on an I-Pod, an extraordinary valedictory work that could have been about Joe himself, with lines about crawling up the mountain to the top.

I talk to Rat Scabies, former drummer with the Damned. He tells me he and Joe had been working together in 1995 on the soundtrack of Grosse Pointe Blank, but that they fell out over that hoary old rock’n’roll chestnut – money. ‘I was stupid,’ he admits. ‘I thought I knew everything from playing with the Damned. But working with Joe was like an entirely new education. He understood how to trust his instincts and go with them every time. I couldn’t believe how fast he worked.’

I run into Mick Jones. He puts his arms around me and kisses me on the cheek. We hold each other. He tells me how he’d loved the message I’d left on his voice-mail after seeing the JOE STRUMMER R.I.PUNK graffiti on Christmas Day; it had touched Mick as deeply as it touched me. He tells me how great the Fire Brigades Union have been, and that the police have behaved similarly. At the Chapel of Rest where Joe had been laid in Somerset a sound system had blared out 24-7. When the police came round in response to complaints from neighbours, and were told it was Joe who was lying there, instead of telling them they must turn down the music they responded by placing a permanent two-man unit outside the chapel: a Great Briton getting a fitting guard of honour, an irony Joe would have appreciated as his mourning bredren consumed several pounds of herb.

Pearl Harbour, Paul’s ex-wife, is there, talking to Joe Ely, the Texan rockabilly star who had often played with the Clash. She tells me how this trip has brought closure for her by bringing her back to what, she admits, was the happiest time in her life.

A moment later Tricia – Mrs Simonon – comes over as Pearl departs and proceeds to tell me how the absent Clash manager Bernie Rhodes had been contacted and invited to come to the funeral, but after the usual over-lengthy conversation it was impossible to discover what Bernie really felt or thought. ‘It seemed that he was more intent on getting on to the next agenda, which was that he desperately wanted to be invited to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction for the Clash next March. What he didn’t realize was that it was already decided that he would be invited.’

‘I always had a soft spot for Joe,’ Bernie later told me. ‘But I couldn’t go to the funeral because I didn’t like the people he was hanging around with.’

Joe and Mick had both wanted a re-formed Clash to play at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. But the one refusenik? Paul Simonon, painter of Notting Hill. Trish admits that the last communication Paul had from Joe was on the morning that he died. Joe sent Paul a fax – he loved faxes, hated e-mails – saying, ‘You should try it – it could be fun.’ Paul, however, was adamant that the group shouldn’t re-form for the show.

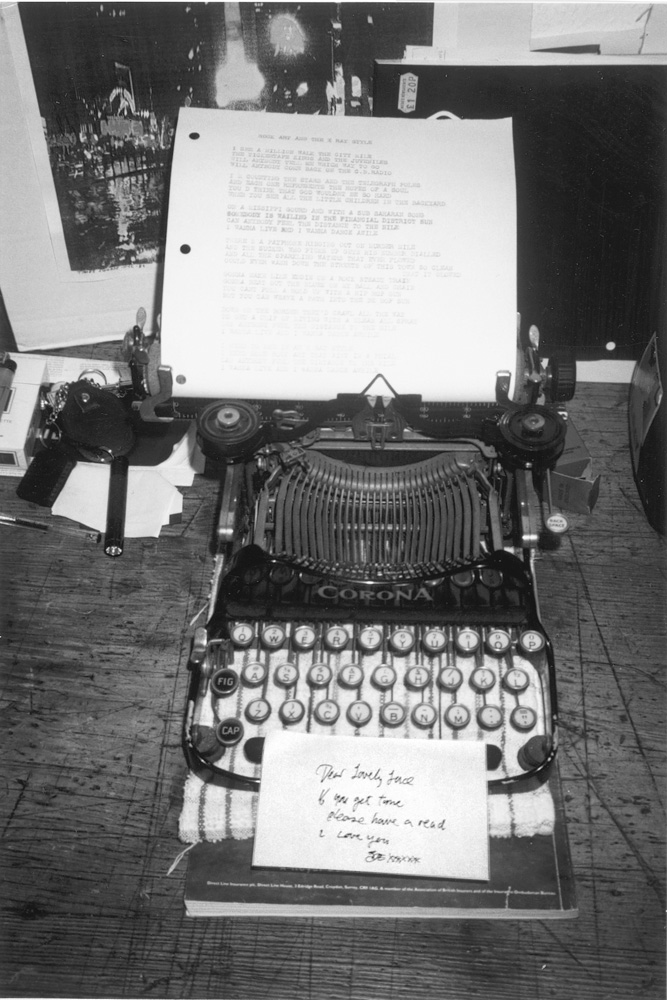

Never too computer-literate, Joe wrote on a typewriter to the end. (Lucinda Mellor)

Next I find myself in a long conversation with Jim Jarmusch’s partner, Sara Driver, who commissioned Joe to write the music for When Pigs Fly, a film she made in 1993, starring Marianne Faithfull, that suffered only a limited release after business problems, and Bob Gruen’s wife Elizabeth. Jim is sitting next to us, deep in conversation with Cosmic Tim, a mutual friend of Joe and myself, from completely separate angles of entry. I had walked into the main upstairs bar as Cosmic Tim was standing on the stage with a microphone. It was the usual stuff that had gained him his sobriquet, and I groaned inwardly. ‘And this man Baba had been to the mountains of Tibet and lived there for twenty-five years, meditating.’ Other people in the packed crowd were groaning too (‘Get on with it.’). But then Cosmic Tim turned it around: ‘And one day when he returned to London, I was walking down Portobello Road with Baba when I see Joe walking towards us. I cross the road, and Baba and Joe look at each other. Suddenly, Baba calls out, “Woody!” (Joe’s nickname from The 101’ers.) And Joe looks up and shouts, “Baba!”’ According to Tim, Baba and Joe had known each other at art college. At length Sara, Elizabeth and myself discuss the state of depression in which Joe was regularly mired, and that most of the tributes to him that day are utterly omitting. Sara says how Jim used to refer to him as ‘Big Chief Thundercloud’. She also tells me how Joe had an enormous crisis when he was on tour in the States singing with the Pogues: he had fallen deeply in love with a girl and wanted to leave Gaby for her. Although he didn’t, in some ways it was the end of his relationship with the mother of his children. (This was a period when I remember Joe seemed even more in turmoil than usual, an air of great anger about him.)

The party is thinning out a little. It is 11 o’clock. I’ve got a slight headache. I leave and walk down to Ladbroke Grove tube station with Flea, Mick’s guitar roadie, and get home around midnight. I fall asleep on the sofa.

3

INDIAN SUMMER

1999

7 November 1999

In a shrine-like case in the seedily glitzy foyer of Las Vegas’s Hard Rock casino stands a guitar once owned by Elvis Presley. ‘What would Elvis think?’ groans Joe Strummer, here to play a show on his first solo tour in ten years. This distress seems a trifle exaggerated, as though Strummer is trying to force himself into the character of a 47-year-old bad boy rocker. ‘This case is only plexiglass: we could smash it open and have the guitar out of there before anyone noticed,’ he continues. Is this a confrontational posture he feels he should adopt in his job of Last Active Punk Star?

The frozen grins on the faces of those around him – his wife, an old friend from San Francisco, myself – suggest this is not what we want to hear: there seems a certain anxiety amongst us that, to prove his point, Strummer might carry out his threat, and that within seconds we will be shot to death by security guards. Thankfully, a fan approaches him for an autograph, the moment passes, and he makes his way backstage for his performance.

As a stage act, the reputation of the Clash was almost unsurpassed. Championed by many as the most exciting performing rock’n’roll group ever, there’s recently been the release of a live record, accompanied by a Don Letts’ documentary, Westway To The World. If ever there was a time to jump-start his solo career, this was it. Strummer seized the moment: he released an excellent album, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style; and took off on a seemingly endless tour, which is how I come to find him in Las Vegas.

Standing with him at the Hard Rock casino’s central bar at 4 in the morning after many post-show drinks, I tell him I’d had the impression that for years he had been going through an ongoing minor nervous breakdown. He balks at this, but initially will admit to having been locked into a state of long-term depression: ‘When people have nervous breakdowns, they really flip out. We shouldn’t treat them flippantly. It was more like depression, miserable-old-gitness.’

How long were you depressed for?

‘About five minutes. Until I had a spliff.’

A moment later he tries to wriggle out of even this admission: ‘I’m not claiming to have been depressed. All I’ll allow is that I didn’t have any confidence and I thought the whole show was over: you can wear your brain out – like on a knife-sharpening stone, run it until it shatters – and I just wanted to have some of it left.

Assisted by his now four-year-old marriage to Lucinda, his second wife, Strummer seems to have found a relative peace; Lucinda is credited by many around him with pulling him out of his malaise.

Christened John Mellor (‘without an “s” on the end, unfortunately: if there was, I’d have pulled more women,’ referring to the game-keeper’s surname in Lady Chatterley’s Lover), he was born in Ankara. His background would seem to show why Mick Jones once expressed amazement to me at how hard and tough a worker Strummer could be. For his father’s profession of career diplomat didn’t arise from any position of privilege, quite the opposite. ‘He was a self-made man, and we could never get on,’ says Strummer.

The musician’s grandparents had worked as management on the colonial railway network in India. ‘My father was a smart dude: he won a scholarship to a good school, then won another scholarship to university. When the war broke out, he joined the Indian army. My mother and father met in a casualty ward in India – she was working in the nursing battalion. After the war he joined the Civil Service at a lowly rank.’

Strummer’s earliest memory was of his brother, who was eighteen months older, ‘giving me a digestive biscuit in the pram’. He still is unable to assess what it was that led David to commit suicide. ‘Who knows? You can’t say, can you?’

Clearly this would have seemed a crucial, motivating catalyst in the life of the person who became Joe Strummer. How did it affect him? ‘I don’t know how it affects people. It’s a terrible thing for parents.’ He pauses for a very long time, until it becomes evident that this is all he is prepared to offer.

If it hadn’t been for punk, what on earth would have happened to Joe? He didn’t last too long at art school. After that, the only upward career move he seemed to have made was when he decided to stop being a busker’s money-collector and to become a busker himself – but even that worried him, he tells me, because he thought it might prove too difficult. It was this that led to him playing with The 101’ers, from which he was poached to become the Clash’s singer. ‘There is a part of Joe that is a real loser,’ says Jon Savage, author of England’s Dreaming, the definitive account of the punk era. ‘That’s what he was in his days as a squatter. And it’s that that comes across in his vocals, which was why people could identify with them so much.’

I tell Joe that Kosmo Vinyl, the unlikely named ‘creative director’ of the Clash, once said to me that if it hadn’t been for punk the singer would have ended up a tramp.

‘Yeah,’ he agrees, without a moment’s thought. ‘When I was a kid I knew that I was never going to make it in the thrusting executive world. I love picking stuff out of skips. A few bum records and I’ll be away with my shopping-trolley.’

I ask Joe Strummer what he learnt from his years in the wilderness. ‘Any pimple-encrusted kid can jump up and become king of the rock’n’roll world,’ he says, voicing something to which he has clearly given much thought. ‘But when you’re a young man like that you really do glow in the light of everyone’s attention. It becomes a sustaining part of your life – which is something that is rotten to the core: you cannot have that as a crutch, because one day you’re going to be over. So obviously I learnt that fame is an illusion and everything about it is just a joke.

‘I don’t give a damn any more. I’ve learnt not to take it seriously – that’s what I’ve learnt. And I’ve also learnt that because what you do is sort of interesting, doesn’t mean you’re any better than anyone else: after all, we’re not exactly devising new forms of protein. If they say, “Release this record because otherwise your career is finished,” and I don’t want them to, then I just won’t do it. I’m far more dangerous now, because I don’t care at all.’

4

STEPPING OUT OF BABYLON (ONE MORE TIME)

2003 (1952–1957)

Moving at a fast pace, Paul Simonon and I are cutting along a narrow rocky mud path that splits the wet grass on this high stretch of Scottish flatland. In a soaking spray of fine rain we have been climbing for twenty minutes. But the moment that we had stepped onto this level plateau the downpour had stopped: damp odours and mysterious scents are all that saturate us now. In the dagger-cold water of a lochan, we stash two cans of beer for our return journey. On the far bank a frog croaks irregularly.

Lusher and even more magical than its much larger, bleaker neighbour of Skye, this is the remote Inner Hebrides island of Raasay, up towards the northern tip of its twelve mile length. Thanks to an abiding impression of all-pervading strangeness, however, we feel we could as easily be on the other side of the moon as on the far north-western periphery of Europe. But you can’t avoid that feeling of being out on the edge. For miles around there are no other human beings, only a vast, amorphous silence, the soundtrack to the greyish-blue wild mountain scenery that juts around us; you can almost hear the clouds clashing on the highland rock and rustling on the purple heather.

As we push on each turn of a corner seems to brings a new microclimate, announced by a gasp of angular wind, like a message from a spirit: now the cloud cover is dashed away and a crisp blue sky sets in relief the Cuillin, Skye’s looming mountain peaks, a few miles across the Sound of Raasay; in this sudden sunlight the sea turns azure, the rough breakers crackling and glistening. After our steep, wet, upward hike, the flat stretch has come as a relief. We don’t know there is a far more arduous climb still to come: finally perched on a rock cairn at the top of that tough ascent, we can see both east and west coasts of the isle of Raasay, three miles apart.

Tough, gritty, awkward, dangerous, an astonishing terrain of primal, pure, mysterious beauty … It is little surprise that one of the descendants of Raasay – John Graham Mellor, known to those outside his blood family as Joe Strummer – has many of the same qualities as the island itself. Although he’d marked it in his diary for the summer of 2003, Joe himself never made it to Raasay; in the years immediately preceding he had been making a conscious effort to reacquaint himself with the Scottish roots on his mother’s side, an effort to redeem the previous thirty or so years when he admitted he had neglected this part of his past. ‘I’ve been a terrible Scotsman, but I’m going to be better,’ Joe said to his cousin Alasdair Gillies at the wedding of their cousin George in Bonar Bridge, three weeks before he died.

To the east, across the deepest inshore water in Britain, sits the mainland of Scotland and the mountain peaks of the Applecross peninsula, rising to over 2,000 feet and tipped by streaks of white quartzite. Opposite it, down towards the Raasay shoreline, lies our destination. Paul Simonon and I are here to find the earliest known home of Joe Strummer’s Scottish ancestors: the rocky, heathery, hilly path that at times we have to hang on to with our fingertips that we are following is the same one that Joe’s grandmother, Jane Mackenzie, would have taken to school. Donald Gilliejesus (‘servant of Jesus’), a stone mason, from near Mallaig on the Scottish mainland, arrived to repair Raasay House, destroyed by English Redcoats after ‘Bonnie’ Prince Charlie hid on the island in 1746 following the Jacobite Rebellion against the English crown. The house at Umachan was built in the early 1850s after the Gillies fled from the ‘clearances’ – the savage requisitioning of small-holdings by landowners – on the south of Raasay. Built by Angus Gillies, the great-grandson of Donald, it was inherited by his son Alastair Gillies. The second of Alastair’s ten children was Jane, born in 1883; Joe’s grandmother would walk barefoot to school along the same path Paul and I had clung to.

We head sharply down, across a lazy burn, past further cairns of stone. On our right there is what appears to be a natural amphitheatre, and a clearly evident ancient burial mound rising out of the greeny-brown terrain. Finally we are standing amidst waist-high bracken on a precipitous ledge, looking down on where we have been told Umachan should be. Between us we have distributed Paul’s canvases, paints and an easel, which have become a burden: we hide them in some undergrowth. Paul, something of a gourmet, tells me how in London he had popped into Bentley’s Oyster Bar in Swallow Street for a dozen oysters and a bottle of Chablis whilst buying the hiking shoes he’s wearing; it’s a long way from heating up flour-water poster-paste on a saw to eat, as Paul did in the early days of the Clash at Rehearsal Rehearsals. But a nourished belly and well-shod feet can only mark us out as the useless city slickers we are: we can find no trace of the home of Joe Strummer’s ancestor.

At a quarter to one, lunchtime on Friday 12 September 2003, my phone rings. It is Paul Simonon. ‘I think you’d better pack your bag, Chris. On Sunday I’m going up to Raasay off the Isle of Skye to do a painting of the house Joe’s grandmother used to live in. You should come with me.’

The Scottish Herald has commissioned Paul to paint a landscape of Rebel Wood, the forest on the Isle of Skye dedicated to Joe Strummer. Paul Simonon is the only member of the Clash to have carved out a non-musical career; returning to his original love of painting, and utilizing contacts he caught along the way as a member of such a prestigious British group, he has made a name and money as a figurative painter. Paul has agreed to paint the wood, but also will supply what he believes is a better idea: a picture of the ruined house in Umachan on Raasay. Iain Gillies, Joe’s cousin, had told us about these ruins.

As I am to discover, our expedition forms part of an experience that will bring some form of ending to the former Clash bass player for the thoroughly unexpected death of his former lead singer. During our time together, Paul emphasizes on several occasions that Joe was his brother, ‘my older brother’.

Every year film director Don Letts and his wife Grace throw a garden barbecue at their Queen’s Park home on August Bank Holiday Monday – a sort of refuge for the over-forties and under-tens from the Notting Hill carnival taking place a mile or so to the south. At the event in 2003, eighteen days before he made that Friday lunchtime call to me to come up to Scotland, I’d last seen Paul Simonon. The smaller 1976 Notting Hill carnival, when black youths and police had violently clashed beneath the elevated Westway in front of Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon, had led to the writing of ‘White Riot’, one of the most contentious songs in the Clash’s canon of work, a tune that at first – before people understood that its lyrics expressed the envy of white outsiders that black kids could so successfully rebel against the forces of law and order – led to suspicions that the group had a fascist political agenda. The 1976 event and the Westway became part of Clash mythology.

In the early days of the group Paul had always seemed shy. In 2001, however, when I had written the text for a picture-book about the Clash by Bob Gruen, the New York photographer, I had been surprised by a change that had overcome the group’s former bass player; as Bob Gruen and I went through hundreds of photographs with each of the group members, he was by far the most articulate. Mick was as warm as ever, but his comments were more jokey and less specific; and although Joe had insisted to Bob Gruen that I should write the text for his book, he surprised me by being the worst of the three interview subjects. Perhaps the photographs, which encapsulated almost the entire span of the career of the Clash, drew up too many memories; he ended up by saying he would write captions himself – and never did. Global A Go-Go, his second CD with the Mescaleros, was being readied for release and Joe was exhaustively – the only way he knew how to anything – promoting it; I could feel tension from Lucinda, on the couple of occasions when I rang up and spoke to her, trying to press Joe to come up with some text. A couple of months later, in the upstairs office that served as a dressing-room at the HMV Megastore on London’s Oxford Street, where Joe and the Mescaleros had just aired the new Global A Go-Go songs to a housefull crowd, he came up and apologized to me for not having come up with the goods.

‘It’s fine,’ I said, telling him I’d used quotes he’d given me over the years. ‘I know you had a lot on your plate, and we came up with something anyway.’

‘But you shouldn’t let down your mates,’ he shook his head at himself.

Anyway, in Don Letts’s back garden it dawned on me that – contrary to everything that you might have expected in 1977 – even before Joe’s passing Paul had become the spokesman and historian of the Clash. At Don’s home that August evening he was especially communicative and open and seemed to feel an urge to talk about the group.

Paul Gustave Simonon was born on 15 December 1955 to Gustave Antoine Simonon and Elaine Florence Braithwaite. Gustave, who preferred to call himself Anthony, was a 20-year-old soldier who later opened a bookshop; Elaine worked at Brixton Library. As happened to Mick Jones, Paul’s bohemian parents split up when he was eight; he and his brother were taken to Italy when about ten, where they lived for six months in Siena, and six months in Rome. There his mother took him to see all the latest Spaghetti Westerns – not just Sergio Leone, but all the Django films also. In London, Paul moved to live with his father in Notting Hill. His father, once an ardent Roman Catholic churchgoer, joined the Communist Party: ‘Suddenly we’re being told we’re not going to church any more. I’m being sent off to stuff leaflets for the Communist Party through people’s letterboxes in Ladbroke Grove. You can imagine what it was like: all these rough Irish or West Indians, hanging out on the steps, and I’m coming up to their letterboxes: “What’s that you’re putting through there?” “Oh, it’s just something about the Communist Party.” Then I figured out, if my dad was such a passionate Communist, how come he was sitting at home and sending me off to do this?