Полная версия

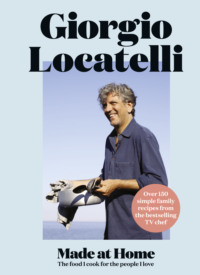

Made in Italy: Food and Stories

You will see the letters DOP (PDO in the UK) and IGP (PGI in the UK) throughout the book. DOP represents Denominazione di Origine Protetta or Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), and it appears alongside the specific name of a product such as Parmigiano Reggiano or prosciutto di Parma. What it tells you is that in order to earn the stamp of the DOP and be allowed to use this name, the food must be produced in a designated area, using particular methods. IGP represents Indicazione Geografica Protetta, or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), which is similar, but states that at least one stage of production must occur in the traditional region, and doesn’t place as much emphasis on the method of production. Whenever you buy Italian produce, look out for these symbols.

Salt should ideally be natural sea salt, and pepper freshly ground and black. Spend a little extra on good extra virgin olive oil and vinegar, and it will repay you a thousand times. And whenever possible buy whole chickens, and meat and fish on the bone, not portioned and wrapped in plastic.

All recipes serve 4, unless otherwise stated

‘You’ll never be a chef, Locatelli!’

‘Pass the prawns…the prawns…where are they…are they ready!’ I had been helping with the cooking in my uncle’s restaurant since I was five years old, but now, at sixteen, and a few months into my first real job, I used to get picked on all the time by the head chef. Now he wanted the prawns and they weren’t ready. The water in the pan was almost boiling. It needed to be boiling, before I put in the prawns, but I panicked and put them in anyway. He saw it and shouted at me, ‘You will never be a chef, Locatelli. You are an idiot,’ and he sent me to clean the French beans.

I couldn’t forget those words: ‘You will never be a chef.’ By the end of the day, I wanted to cry like a baby. I went home and my grandmother was waiting. ‘What does he know?’ she said. ‘Who is he?’ ‘He is The Chef!’ I told her. I would have run away, but as always my grandmother put everything into perspective, and she told me I had to go back and show him. So I went back. And I did show him.

Food, love and life…

My first feelings for cooking came from my grandmother, Vincenzina. But my first understanding of the relationship between food, sex, wine and the excitement of life came together for me very early on, when I was growing up in the village of Corgeno on the shores of Lake Comabbio in Lombardia in the North of Italy – long before I was suspended from cooking school for kissing girls on the college steps.

My uncle Alfio and my auntie Louisa, with the help of my granddad, built our hotel and restaurant, La Cinzianella – named after my cousin Cinzia – on the shores of the lake, on the edge of the village of Corgeno in 1963.

There were eight founding families in the village. The Caletti family, on my mother’s side, was one of them; and on my grandmother’s side, the Tamborini family, along with the Gnocchi family, who are our cousins, and who have a pastry shop in Gallarate, near Milano, in the hinterland, before the scenery changes from city to green and beautiful space, and where the speciality is gorgeous soft amaretti biscuits.

The shop gave me my first taste of an industrial kitchen. I used to love going in there as a kid, because the ovens were so big you could walk into them. In the season running up to Christmas, over and above the other confectionery, they would make around 10,000 panettone (our Italian Christmas cake). It was fascinating to watch the people take the panettone from the ovens, and then, while they were still warm, hang them upside down in rows on big ladders in the finishing room, so that the dough could stretch and take on that characteristic light, airy texture. Years later, when I first started in the kitchens at the Savoy, I felt at home immediately, because I recognized that same sense of busy, busy people, working away in total concentration.

Of course, everyone in Corgeno seems to be some sort of cousin, though none of us can remember exactly how we are related. Six generations of our families are buried in the village graveyard, and the names are etched many times into the war memorial outside the church with the two Roman towers, above the makeshift football pitch where we kids played every day after we had (or hadn’t) done our homework.

Life in the North of Italy is very different from the way it is in the pretty Italy of the South – the idyllic Italy, still a little wild, that you always see in movies. The South fulfils the Mediterranean expectation, whereas the North is the real heart of Europe. Historically we have been under many influences: Spanish, French, Austrian…at home we are only around 20 kilometres from Switzerland, and Milano is the most cosmopolitan city in Italy. In the North I don’t know anyone who hasn’t got a job and everyone comes to the North to find work – the reverse of the way it is in England.

The industrial North of Ferrari and Alessi can be more stark; but somehow I think it has a tougher, more impressive and real kind of beauty than the regions that the English love so much, like Toscano and Umbria. You might not think they are very far down the boot of Italy, but where I come from anything below Bologna is south. In the North, we are famous for designing and making things, things that work properly. Northern Italians always tell jokes against southern Italians, and vice versa. We like to say that, in Roma, if you have to dig a hole in the road it will take eight months; in the North everything will be fixed and running like clockwork in a day. And while most of Italy used to stop for a big break at lunchtime – especially in the South, where it was too hot to work – in Milano and around Lombardia it would be one hour only. The factory whistles would go at 12 noon – the signal for the wives and mothers at home to put in the pasta – and then the road would be full of bicycles and scooters and motorbikes, as everyone shot home to eat and then straight back to work.

In the South, they are used to delicate foods like mozzarella and tomatoes and seafood. In the North, we are proud of our Parmigiano Reggiano and prosciutto di Parma and big warming dishes like polenta and risotto. And if we haven’t used our food to promote our area around the world as strongly as other regions, it is not because it is less important to us, but that we haven’t needed to, because we are known for other things.

Corgeno is a place steeped in history, firstly because of its twin Roman towers and more recently because of its pocket resistance to fascism. On one of the old walls you can see the faded words of one of Mussolini’s slogans that still makes me angry every time I see it, with its call to the youth of Italy to put down their picks and shovels and take up arms. There are many stories in our village of the local men of the resistance who used to hide in the woods where the women would bring them food. One of them, my father’s brother, Nino, was shot on one of his trips, trying to help forty Jewish people to escape over the border into Switzerland.

Below the village is La Cinzianella, only a few steps to the edge of the lake, which I love, especially in autumn, my favourite time of year. Almost tragic isn’t it, autumn? But so beautiful. Early in the morning, you can’t see the lake because it is hiding in a mauve mist, but when it rises the sky is bright blue and the trees around the lake, with their red and gold leaves, stand out clearly against it. And it is so quiet: all you can hear are the birds calling and scudding over the water – and across the lake the faint buzz of motorbikes going at a hundred miles an hour across the superstrada, the straight towards Mercallo, and into the turn, as if they were on a race track.

We are only forty-five minutes drive from the centre of Milano, and right next to the bigger and more famous Lago Maggiore, so now a lot of people from the city come for weekends; they have bought houses, and the village has grown. But when I was growing up, there were only about 2,000 people and everyone knew everyone else: who was just born, who died; it was all-important to our lives.

I remember one of the first new families to move into Corgeno, from Sicilia – the wife worked at la Cinzianella, and we nicknamed one of the kids

Mandarino after the oranges that came from Sicilia. They spoke a dialect that sounded foreign to us, and the father was loud and dramatic when he talked; tragic, comical…so different from my father, who never raised his voice.

Almost everything we ate and drank was produced locally. We even picked up the milk every evening from the window of the house of Napoleone, who kept a few cows. Each family had their own bottles and he would fill them up and leave them for us to collect – in winter outside the window, in summer in the courtyard under a fountain. Later, when I was a young boy and I was working in restaurants abroad, when I came home for the holidays, people would always open their windows to lean out and say hello. They still do. Whenever we go to Corgeno, my wife Plaxy complains that it takes an hour to walk through the village, because someone will always shout, ‘Hey, Giorgio’ – and it always seems to be an ex-girlfriend.

I remember coming back home after one summer when I was a teenager. I stopped in at the tobacconist to buy cigarettes, and by the time I got to our house, my grandmother already knew that I had changed from Camel to Marlboro. That is how small our village was.

My auntie, uncle and my father and mother all worked in the hotel and my uncle ran the restaurant where I worked, too, as soon I was big enough. Later we had a Michelin star, but then we just served good, honest Italian food and on Saturdays we did banqueting and wedding receptions in a big beautiful room at the top of the hotel, looking out over the lake. We used to feed around 180 people and when we were at our busiest, we would make 20 kilos of dough for the gnocchi and everyone, from the waiters to the women who did the rooms, would come into the kitchen to help shape them. In summer, our guests could sit out on the terrace under big umbrellas. If it was raining they gathered inside around a big table in the corridor, and no one ever complained.

There are ten rooms in La Cinzianella, and we would send food to the rooms, too. Every Sunday a well-known gentleman from the village, Luciano, would come to the hotel in his Mercedes, with a woman called Rosetta. Everyone knew that his wife had been ill for a long time and that Rosetta was his mistress. So on Sundays his room would be ready for him from about two o’clock, and by six, six-thirty, he would call us and order a bottle of champagne. I remember my mother would put it on a tray and, of course, somebody had to take it up – all of us young boys wanted to do it, because we wanted to catch a glimpse of Rosetta.

I still remember her – warm and round and womanly, like my auntie Maria Luisa, who was beautiful too, the nearest thing to royalty. Maria Luisa was the only one who had any power over me when I was wayward, and could tell me off without ever losing her temper, unlike my mother, who is quite a nervous woman. When my grandfather died, we sat down for our first meal all together without him, and we all expected that my father would take his place at the head of the table, but Maria Luisa came in and sat down in the place of my granddad and she has been there ever since.

My auntie and Rosetta – for me they represented sexuality, but all bound up with good food and wine and generosity, because by seven-thirty, showered and beautifully dressed, Rosetta and her gentleman friend would come down to eat dinner and we would welcome them warmly; we were part of their lives, and they were part of ours. There was a complicity between restaurateur and guest, which is one of the things I have tried to create in my own restaurant.

Even in the heart of London, I feel we have a special bond with our customers. Eating is not just about fuelling up to get through the day; it is about conviviality, friendship and celebration. I like the fact that people come to us again and again for an anniversary, or a birthday. I want them to bring their kids, so I can take them into the kitchen, and they can help prepare the dessert for their mums and dads. I like to feel that I can come and sit down and chat with them in between cooking; and if I see them on the street one morning, I can invite them into the restaurant for coffee. Sometimes people who have eaten at Locanda, and before that at Zafferano, whom we have known for many years, come to see us after a husband or wife has died, or they have split up, because in a strange, poignant way, we have become part of their lives. For my wife, Plaxy, and for me that is so special; because this is our restaurant, an extension of our family; and everything that happens in it is personal to us. I know how important it is to have that intimacy, because the memories of our relationship with the local gentleman and Rosetta at La Cinzianella have stayed with me all my life.

Antipasti Starters

Pellegrino Artusi

‘It is true that man does not live by bread alone; he must eat something with it.’

Italians are very impatient people. We can’t sit for more than a minute in traffic and we hate to wait for our food. That is why we invented antipasti, which literally means ‘before the meal [pasto]’. When I first came to England, I thought it so strange to see people at parties and weddings standing about having drinks before they ate. Italians just want to get around the table as soon as possible, so the bread can arrive. Not just bread – we also want salami, prosciutto, maybe some marinated artichokes, some olives…We want to enjoy a glass of wine, to talk and argue, because everything we do in a day is a small drama and everyone has an opinion on it – but we need to eat while we are discussing it. Once the antipasti are on the table, that is the signal to relax, get into the mood and interact, because you have to pass the plates and everyone is saying, ‘Oh what is this?’ and, ‘Can I have some of that?’ It is all about conviviality and sharing and generosity.

A few miles from my home in Corgeno, in Lombardia, on the way to nowhere, is the village of Cuirone, with its pale, yellow-washed houses; a place that has hardly changed since I was a child. In the middle of the village is the Societa Mutuo Soccorso, the cooperative shop and restaurant with a bakery attached, where they make fantastic chestnut and pumpkin bread, as well as the big pane bianchi, which is the everyday bread. Inside the bakery, they have a basket that is full of drawstring bags, some gingham, some flowery. Each family makes their own bag, and the bakers know which bread they have, so in the morning when the loaves come out of the oven, the bags get filled up and delivered by scooter.

At one time in our region of Italy, most of the villages had a cooperativa, run by the locals, where everyone could bring their produce to sell and where you could get a simple lunch for not much money. Everything you ate would be produced locally. You have to remember that Italy has only been a united country for not much more than a hundred years. Before that it was made up of different kingdoms, dukedoms, republics etc., each influenced by different neighbours and invading armies throughout its history.

Also in Italy you have a massive geographical change from mountains to coastlines, from the colder North with its plains full of cows giving beef, and milk for cheese, to the hot South, on the same parallel as Africa, where they grow a profusion of lemons, tomatoes, capers and peppers. So in every region, town, and village, they have their own particular ingredients and style of cooking, which of course they will insist is absolutely the right way – and that what everyone else does is wrong.

In Corgeno, the cooperativa was next to my uncle’s restaurant, La Cinzianella, overlooking the lake, and when you turned twenty years old, you were asked to run it for the summer (the year my friends and I took charge we had a fantastic time). But now the space is rented out as a café and restaurant. In Cuirone, though, the cooperativa is still thriving, and sometimes, especially when I come home to visit, my Mum and Dad, and my aunts, uncles and cousins all meet up there for lunch at the weekend. Lunch is at 12.30, and 12.30 is what they mean, so you don’t dare be late.

It’s a very simple place: a large room with a long bar down one side and wooden tables and chairs where the farmers and the old men of the village drink red wine and play cards. But the moment you sit down, big baskets of bread from the bakery arrive with bottles of local wine, and then the plates of antipasti: salami, prosciutto, lardo, carpaccio, local cheeses, artichokes, porcini. As one plate is taken away, more arrive, and so it goes on and on. Then, just when my wife Plaxy, especially, is thinking that there can’t be any more food, out comes a pasta dish – maybe a baked lasagne – and then a fruit dessert.

The antipasti are based around simple produce, just like in people’s homes and most small restaurants. The members of the cooperativa bring whatever they have that is fresh that day, along with ingredients such as artichokes and mushrooms, prepared when they were in season, then preserved in big jars under vinegar or oil, or salamoia (brine). In Italy, things are done differently from in the UK, especially London, where you buy your food, eat it, and then buy some more. Most people in Italy still behave like they did in the old days, when you would always have a store cupboard full of dried or preserved foods because you never knew when there would be a war or some other disaster.

In smarter restaurants, the kitchen would have the chance to show off a little more with the antipasti. In my uncle’s kitchen at La Cinzianella we really worked at our antipasti, bringing out some fantastic flavours, because we knew that this prelude to the meal said a lot about what you were trying to achieve with your food, and about the dishes that would follow. The slicing machine was right in the middle of the big dining room, so everyone could see the cured meats being freshly cut, and we would prepare seafood salads and roast vegetables. Imagine how I reacted the first time I went to a French restaurant and they sent out some canapés before the meal – those tiny, bite-sized things. I was shocked. I thought, ‘If this is what the rest of the food is going to be like, forget it!’ Italians don’t like to fiddle about with fancy morsels, they just want to welcome people by sharing what they have, however simple, in abundance. An Italian’s role in life is to feed people. A lot. We can’t help it.

The traditional Italian meal

In Italy the concept of the ‘starter’ – individually plated dishes that you eat by yourself, just you – is quite a modern thing. Only in the last twenty years or so have restaurants started putting them on the menu. Traditionally, after the antipasti the real ‘starter’ was the pasta course, or first plate (i primi piatti). Then came the second plate (i secondi piatti), which would be meat or fish, and, to finish, fruit or a dessert (i dolci).

When I look at the books I have of old regional recipes, no mention is made of ‘starters’ as we think of them today. One of the books I love most is La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene (Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well) by Pellegrino Artusi. All Italian cooks know about Artusi – he was a great gourmet and one of the first writers to gather together recipes from all over Italy. He published the book himself back in 1891, in the days when Italian food was considered a bit vulgar in ‘smart’ society because the food of the royal courts was French.

Artusi spent twenty years travelling around Italy and his knowledge of regional produce and cooking was remarkable. His stories are full of beautiful descriptions and witty comments, sometimes using old Italian words that I have to look up. I keep his book in my office in the kitchen at Locanda to research ingredients and old recipes. But even Artusi has only a short section on ‘appetisers’, which is really just an acknowledgement of the moment before the meal when you show off your capacity to bring out food of a high quality. (Interestingly, he says that in Toscana they did things differently from other regions and served these ‘delicious trifles’ after the pasta, not before.) Artusi talks about various cured meats, caviar and mosciame (salted and air-dried tuna), but the only ‘recipes’ he gives for appetisers are a selection of crostini: fried bread topped with ingredients such as capers, chicken livers and sage, or woodcock and anchovies.

Traditionally, the kind of antipasti you ate was determined by where you lived. Around the coast there would obviously be more seafood, while inland there were cured meats. Every region would have different breads to serve with the antipasti: light, airy breads in the North, white unsalted bread in Toscana and enormous country loaves made with harder flour in the South – fantastic for bruschetta, which these days has become rather elevated in restaurants, but is really just chargrilled stale bread with a bit of garlic and tomato rubbed over it and some oil drizzled on top.

Even now, food in Italy is very regional, but after the Second World War, when everything became more abundant and people began to travel more, some chefs started to be a little inventive and borrow ideas for their antipasti from other regions, and from the street food you see cooked in cities such as Napoli by vendors with gas burners on trolleys: arancini (rice balls), crocchette (mashed potato croquettes), panzerotti (little pasties filled with meat, cheese, tomatoes or anchovies, then deep-fried), mozzarella in carrozza (mozzarella ‘in a carriage’ – deep-fried between slices of bread), and frittelle (fritters filled with artichokes, mushrooms or prawns).