Полная версия

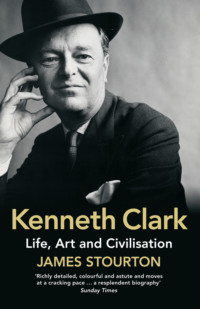

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation

The British habit of sending their offspring away to boarding school at the age of seven or eight, which Clark abhorred (but repeated with his own children), was, he believed, ‘maintained solely in order that parents could get their children out of the house’.34 His parents’ choice of preparatory school was Wixenford, a fashionable school in Hampshire. Like most schools of its type, Wixenford was faintly ridiculous, and Clark probably made the place sound even more ridiculous than it actually was, with shades of Llanabba Castle, the school from Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall. Wixenford was a feeder for Eton, and in Clark’s description expended more effort on entertaining parents than educating children. It was housed in mock-Tudor buildings and had a very pretty garden, ‘leading to an avenue of pleached limes, under which, it was alleged, school meals were served in the summer term’.35 Lord Curzon was an alumnus, and the pupils were the children of the upper classes and of American and South African millionaires.

By the standards of the time Wixenford was an easy-going and benign establishment, whose staff Clark characterised as a ‘pathetic group of misfits and boozy cynics’. The only master with whom he had any kind of rapport was the art master, G.L. Thompson – known as ‘Tompy’ – who introduced him to the drawing methods of the Paris art schools of the 1850s. Wixenford encouraged the boys to put on theatrical productions and write for the school magazines, and Clark did both. He staged a revue incorporating all his favourite music-hall songs. Harold Acton, the future leader of the Oxford aesthetes, was a contemporary at Wixenford. He edited a magazine, and it was probably for him that Clark produced his first literary effort, an article entitled ‘Milk and Biscuits’ (which referred to those breaks added to the school’s curriculum, so Clark argued, in order to please the parents). Acton in his memoirs remembered Clark as a mature prodigy, ‘walking with benign assurance in our midst, an embryo archbishop or Cabinet Minister’, and mischievously added, ‘Since those days he seems to have grown much younger.’36 Wixenford provided one revelation for Clark. The ‘school dance was the first time I had met girls and I was enchanted beyond words, not by anything tangible, but the aura of femininity. Incipit vita nova.’*37 For good and ill, this enchantment would remain with him for the rest of his life. He enjoyed his days at Wixenford, and was described in his leaving report as ‘a jolly boy’ – a description that would be beaten out of him at Winchester.

When Clark looked back on his childhood world of Edwardian England he described it as a vulgar, disgraceful, overfed, godless social order, but admitted that he had enjoyed it. He also allowed that the period was a golden age of creativity: ‘Well it always seems to me that there was a great deal to be said for living between 1900 and 1914, because it wasn’t simply the age of the Edwardian plutocrat; it was also the age of the Fabians, of extremely intelligent people like Shaw and Wells. It was the age of the Russian Ballet. It was the age of Proust. It was the age of Picasso, Braque and Matisse. In fact almost everything I enjoy in what is called modern civilisation was in fact evolved before 1916. I do think the 1914 war was the great turning point in European civilisation.’38 When he came to tell the story of Civilisation on television he ended his account in 1914.

* Clark senior bought the Imperial Hotel in Menton with his winnings. On another occasion he acquired a golf course at Sospel and built a large, ugly hotel on it, also designed by Tersling, which he later gave to his son. Curiously, the art historian R. Langton Douglas and Sotheby’s chairman Geoffrey Hobson were partners in the golf course. (Information from the late Anthony Hobson.)

* His friend Joan Drogheda wrote to complain about this passage in his memoirs, stating that most servants did not treat children in the way he claimed, nor were they resentful of their employers, and that he had ‘struck the wrong note’. Letter from Lady Drogheda, 19 February 1972 (Tate 8812/1/4/36).

* It would also provide a mutual interest with Val Parnell and Lew Grade when Clark was chairman of ITV. Their background was in music hall and variety.

* ‘Thus begins a new life.’

3

Winchester

Winchester helped to open for me the doors of perception.

KENNETH CLARK, Another Part of the Wood 1

Winchester was a curious choice of public school for Clark’s parents, and is perhaps best understood in negative terms: it was not Eton or Harrow. Clark senior had a horror of the nobility, who – as he liked to point out – only ever wrote to ask him for something. He did not want his boy turning into a snob, and he and Alice would no doubt have felt uncomfortable at speech days – had they ever bothered to attend. The idea of sending Kenneth to Winchester almost certainly came from Wixenford. Even in an establishment so academically lax, it was recognised that the boy was exceptionally promising. His sponsor in the entry book at Winchester is given as P.H. Morton, Wixenford’s headmaster. Kenneth was the only boy in his year to go to Winchester.

Winchester is one of the great schools of England, with a distinctive and cerebral reputation. Founded in 1382 by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, as a school for poor scholars, it maintained a standard of academic excellence that was daunting to all but the cleverest boys. Clark painted a miserable picture of the school in his early years there, but pointed out that ‘All intellectuals complain about their schooldays. This is ridiculous.’2 He believed that they tended ‘to regard bullying and injustice as a personal attack on themselves, instead of the invariable condition of growing up in any society’.3 Ridiculous or not, Clark certainly took bullying personally. An additional privation was the effect of arriving at the school in the middle of World War I, which meant little heat and very poor food. Clark, who all his life was mildly epicurean, suffered accordingly. He also missed the soothing feminine influences of Lam.

Like all English public schools, Winchester had its peculiar rites and customs, including a vernacular language called ‘notions’. It was an academic hothouse, with a dual emphasis on studying the Classics and sporting achievements. When Clark was later honoured by the school in the Ad Portas ceremony, its highest honour, he said, ‘Winchester was once famed for the uniformity of her sons: a uniform excellence, no doubt, but one obtained at the expense of individual fulfilment.’ This was to be one of several hindrances he felt at Winchester, since his trajectory was not to follow the conventional Classics route to scholarly recognition. He chose instead to walk an individual path through the study of art and its history. Arriving from Wixenford poor in Latin and without Greek, he was underrated during his early years at Winchester until Montague John Rendall, the school’s unconventional headmaster, recognised his singularity.

The second problem Clark faced was his total unpreparedness for the tribal cruelties inflicted by older boys on younger ones. As a mollycoddled only child who had never experienced sibling rough-and-tumble, nor yet learned teenage cunning, the thirteen-year-old Clark was to experience probably the greatest trauma of his life in his first week at Winchester. He tells the story with some emotion in his autobiography. On the school train he addressed a handsome senior boy, who ignored him. The boy turned out to be the head prefect of his house, and on arrival at the school Clark was summoned to the library, where he was instructed to ‘Sport an arse’ – i.e. bend over – and received several painful strokes of a cane for his bumptious behaviour in speaking to an elder. The prefect’s children were later to become close friends of Clark’s children, but he never revealed the story to them.

Tony Keswick,4 who became Clark’s closest friend at Winchester, recalled that first day at the school. The new boys for the 1917 spring term had arrived on an early train, been abandoned and got over their tears. He and Clark were beginning tentatively to make friends when the main school train arrived. There was a tremendous cacophony of voices, at which point ‘a river, an avalanche of boys poured in’. Clark turned to Keswick and said, ‘This is dreadful, isn’t it?’ Keswick agreed, and later said, ‘It’s the most vivid memory I have of him.’5 Clark’s torments were only just beginning. On the second evening Clark encountered a prefect who was an artist, and rashly offered an opinion on his work. ‘Bloody little new man. Think you know all about art. Sport an arse.’ In addition to these beatings, Clark found himself regularly cleaning fourteen pairs of prefects’ shoes. ‘In the twinkling of an eye,’ as he put it, ‘the jolly boy from Wixenford became a silent, solitary, inward-turning but still imperfect Wykehamist.’6 The traumas of his first week at Winchester gave him a bruise from which he never fully recovered, and a lifelong horror of upper-class tribalism.

The school was divided into ten ‘houses’ of about thirty boys each, and Clark was placed in the house of Herbert Aris, known as ‘the Hake’, with whom he had no understanding or sympathy. Houses were remarkably individual, and took their character from the nature of the housemaster. Aris was Clark’s housemaster for three years, until 1920, when he retired on his wife’s money to a country estate and his place was taken by Horace Jackson, ‘the Jacker’. The house still stands as it did in Clark’s day; a line of small brick houses at 69 Kingsgate Street, pleasant cottage architecture with internal panelling. Aris – whose motto appears to have been ‘Go hard, go hard’ – wanted to make a man of Clark, who describes in his autobiography how Aris encouraged him to learn boxing, and exclaimed, ‘I want to see that big head knocked about.’7 After a few weeks he asked Clark how he was getting on. ‘I am enjoying it sir.’ Aris was furious: ‘I don’t want you to enjoy it, I want you to get hurt.’ Clark wrote a witty dialogue entitled ‘The Housemaster’ reproducing this scene. It is the earliest surviving manuscript in the Saltwood archive, and it suggests a more humorous gloss, with Clark responding ‘(penitently & repressing tears – or is it laughter! – with difficulty) So sorry sir.’

Clark’s portrait of Aris in his autobiography was of a small-minded sadist, but he records Mrs Aris as charming. Their son, John Aris, later wrote to Clark remembering his mother lending him a book on Ruskin (which Clark acknowledged had a crucial influence on his life) and allowing him to play her piano. He added, ‘You might be right about my father as a schoolmaster, though your contemporaries would not all agree … He was not unkind but he was a man of rather simple austerity, and I believe he was then preoccupied with those who went from Winchester to France [i.e. to war]. I hope you have not misjudged him.’8

Clark’s second housemaster, ‘the Jacker’, was something of a Winchester legend. A school manuscript describes him as ‘a ferocious little man who didn’t suffer fools – wounded in the war, he became an ardent militarist but he collected china and knew about woodcuts. He had many unlikeable qualities and was not by nature affectionate. It was said he was only interested in athletes.’9 Despite their obvious differences, Clark thought he treated him very fairly. Jackson hated conceit. When someone towards the end of Clark’s time at the school asked him what he was going to do afterwards, Clark answered, ‘Help Mr Berenson to produce a new edition of The Drawings of the Florentine Painters.’ Jackson, whom he had not observed, remarked ‘Bloody little prig.’10 He was not the last to voice this sentiment. Equally often quoted, though probably misinterpreted, was the Jacker’s remark when sitting between Clark and Keswick, whose father was a leading Hong Kong nabob, ‘Never, never again will I have the son of a businessman in my House.’11 In fact there were many such children in the house, and as Jackson’s obituary stated, ‘he could crack a joke, maybe with an edge to it’.

Like most clever and sensitive boys at school, Clark found refuges. The most important was ‘the drawing school’ or art room. On his third day he called on the art master, Mr Macdonald – ‘a kindly, agreeable person but the laziest man I have ever known’. Winchester frowned upon extra-curricular activities, and Macdonald did not have many pupils, so it was probably with mixed feelings that he eyed the eager young student. Fortunately, Clark admired two prints by the Japanese artist Utamaro on the wall, and Macdonald invited him to ‘come next Sunday, I have some more in those drawers’. Clark devoured the astonishing collection of prints by Utamaro, Hokusai and Kunyoshi – later, he was always to have Japanese prints in his own art collection. He had already resolved that he was going to be an artist, and this decision informed the rest of his time at Winchester. His Sunday afternoons with Mr Macdonald ‘were among the happiest and most formative in my life. They confirmed my belief that nothing could destroy me as long as I could enjoy works of art.’12

Macdonald taught Clark to draw plaster casts of sculpture – a training, as he ruefully observed, that would be more useful to him later as an art historian – and each year he duly won the school drawing prize. The kind Mrs Aris showed him copies of The Studio, the bible of the Aesthetic Movement, and it was there that he encountered the work of Aubrey Beardsley, who together with the illustrator Charles Keene was the main influence on his drawing. Years later it was these two artists that Clark chose to lecture about at the Aldeburgh Festival. Several drawings survive in the Tate archive in the modish naughty nineties style of Beardsley, occasionally signed ‘KCM’, mostly male nude studies. Others show the cross-hatching manner of Keene. It was Mr Macdonald who introduced him to one of his later gods: ‘I remember vividly the first moment at which my drawing master at school pulled out of a cupboard some photographs of Piero della Francesca’s frescoes at Arezzo, then seldom reproduced in any book. Even upside down, as they emerged, I felt a shock of recognition.’13

Apart from the art room, Clark’s other refuge was the school library. This had practically no art books except Richard Muther’s monograph on Goya.14 But it did contain the set of volumes that were to have the greatest influence on his life, The Collected Works of John Ruskin in the edition edited by Cook and Wedderburn (1903–12). ‘I expected them to be about art. Instead they were about glaciers, and clouds, plants and crystals, political economy and morals.’15 If the works of Roger Fry and Clive Bell were more contemporary and easier to read, the Ruskin volumes ignited a slow-burning flame that would last all his life. They profoundly influenced not just the way he looked at and described works of art, but also his political and social attitudes. Among his own books, Clark’s favourite was to be his selection of the Victorian writer’s work, Ruskin Today. Almost as important was his discovery of Walter Pater,* his writings on art and his story in Imaginary Portraits of the nihilistic young patrician ‘Sebastian Van Storck’, in whose ‘refusal to do or be any definite thing I recognised a revelation of my own state of mind’.16 Clark’s unhappiness at school and rejection of the sporting life at Sudbourne fed these melancholic feelings. He was to be prone to ennui all his life, and in later years only action and work would enable him to overcome his fear of boredom.

At home during the holidays, the teenage Kenneth Clark was a withdrawn figure. To the annoyance of his father, he still refused to go out shooting. Phyllis Ellis described him at Sudbourne during this period: ‘They also had a pianola in the billiard room. When young Kenneth came back from school, on holiday, we used to go through the pianola rolls. And he’d take me out in a boat on the lake. It was extraordinary, a boy of fourteen spending his time with a four-year-old girl, but he was always different from other people and perhaps, like me, a lonely child. He wasn’t very happy at that time.’17

It was a great disappointment to his father that Kenneth was not interested in the shoot, and this, combined with the upheavals of the war, called into question the future of the estate. No doubt Clark’s mother also longed to be free of the burden of organising house parties, and his father decided to put Sudbourne on the market in 1917. We can only imagine the distress felt by Clark’s father at selling what he had spent so long creating. He almost sold the property to Walter Boynton, a timber-man who offered £170,000 but was unable to pay. The estate was therefore auctioned the following year in parcels, but most lots failed to find buyers. It was a disastrous time to sell, with a quarter of all English estates being for sale. Finally, in 1921, the industrialist Joseph Watson, shortly to become the first Baron Manton, stepped in and bought it with a reduced acreage for £86,000, representing a massive loss for the Clark family.*

The Clarks moved to Bath, where they remained for most of Kenneth’s schooldays. His father would spend all day at the club playing bridge and billiards, but Kenneth could never fathom what his mother did, apart from visit antique shops. He became very fond of the city, and was unexpectedly to spend a school term there.* Perhaps surprisingly, he was a good sportsman – an improbably skilful bowler for the cricket team, and he even won a running prize. One day after a long run he was taken ill with pneumonia. So serious was his condition that he was removed from the school for a term. He was already showing signs of the hypochondria that dogged him for the rest of his life. Always liking to project himself as an autodidact, he described being ill as ‘the only time at which I learnt anything of lasting value’.18 He passed his days reading and playing Chopin on his pianola, and was later to view this period as crucial to his development: ‘My mind was in a plastic condition, and for the last time I was able to remember a good deal of what I read.’19 He was devouring English poetry of the seventeenth century, particularly Vaughan and Milton; Chinese poetry of the ninth century in Arthur Waley’s translations; Ibsen, who taught him the complexities of human motivation; Samuel Butler, a different kind of scepticism; and of course Ruskin, ‘whose Unto This Last was the most important book I ever read’. He also did most of his novel-reading at this period, enjoying the works of Anatole France, Joseph Conrad and Thomas Hardy.

The end of the war produced one extraordinary benefit without which no aesthetic education of the period was complete – the arrival in England of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. ‘It was an intoxication,’ Clark wrote, ‘even stronger than Beardsley.’20 The sight of works such as Scheherazade and The Firebird was an escape from the dreary parochialism of school into a dream world. Who it was that took Clark to see the Ballets Russes is a mystery, but it may have been Victor ‘Prendy’ Prendergast, a slightly older boy in the same house. Clark described him as ‘a great influence on my life at Winchester. He was a dyed in the wool aesthete and a Yellow Book character.’21 They shared a mutual interest not only in ballet but also in modern art. Prendy must have been a sympathetic figure, but Clark lost sight of him at Oxford, and the Winchester old boys’ register simply says he ‘travelled and did literary work’.

If the Ballets Russes gave Clark his first taste of international modernism, this education continued at the modest London gallery that put on the first one-man show in England of just about every major European avant-garde artist, the Leicester Galleries. It was in these unpretentious surroundings, under the gentle guidance of its director Oliver Brown,22 that Clark discovered the joys of collecting, at this time usually drawings under £5. When he was sixteen a godfather gave him £100 with which to buy a picture, and he was struck by an oil of a primitive-looking boy by an artist he had never heard of, Modigliani. He reserved it, but at the last minute – trying to imagine it hanging alongside his parents’ Barbizon works – his courage failed him and he cancelled the purchase. As a testament to its quality, today it hangs in the Tate Gallery.

The man who more than any other was responsible for the transformation of Clark and his growing confidence at Winchester was the towering, eccentric, quixotic headmaster, Montague John Rendall. He was a Harrovian bachelor who devoted his life to the school, and whose old age was spent catching up on what old boys were doing from the newspapers. He is one of the greatest and most striking headmasters of his era, in the class of J.F. Roxburgh, the founder of Stowe. Monty Rendall responded to originality and cleverness in boys, and was the first person outside the family circle fully to recognise Clark’s potential. Clark always spoke of him later with affection, claiming ‘he saved me’.

What was Rendall like? Clark thought he combined the muscular Christianity of Charles Kingsley with the aestheticism of the pre-Raphaelites. He was something of an actor, both grave and absurd, who affected a shaggy Edwardian moustache and always wore a tie unknotted but dragged through a key ring. One contemporary described him: ‘Monty was so marvellously, so intoxicatingly, so memorably, so splendidly funny … he came from a generation who had the courage to dramatise itself.’23 Chivalry was the cardinal virtue for Rendall, and he commissioned a medievalising triptych in praise of it, which he bequeathed to the school. He believed, wrote Clark, in ‘that mixture of learning, courtesy and fair play, which seemed to him the ideal of a gentleman either in Mantua or Winchester College’.24 To Clark, as to many Wykehamists, Monty Rendall was always the loveable, inspiring teacher who introduced him to Italian art.*

Rendall set up a study centre at Winchester with images of Italian drawings and paintings. He produced detailed and beautiful wall charts of the painters of northern Italy – Florence, Umbria and Siena – in which he referred to Clark’s future mentor Bernard Berenson. His rooms were full of Italian art and Italianate contemporary art. He even created an Italian garden in front of the headmaster’s house, cheekily known to the boys as ‘Monte Fiasco’. Above all Rendall was an inspired lecturer, and Clark had his eyes opened to the wonders of Giotto, Fra Angelico, Pisanello, Botticelli and Bellini, all presented with the kind of humorous asides that he was later to employ himself. The lectures were a mixture of learning from Berenson, Roger Fry and Herbert Horne, but Rendall had bicycled around Italy and actually seen all the works of art he described, so his lectures had a directness that spoke to the young Clark. Every year Rendall would give his most memorable lecture, on St Francis of Assisi. Fifty years later, when Clark made the third episode of Civilisation and spoke of the saint, many old Wykehamists – and he acknowledged that they were right – heard echoes of Rendall. It was these lectures and exhibitions at Winchester that predisposed Clark to work with Berenson. When he was leaving the school Rendall gave him a copy of Berenson’s A Sienese Painter of the Franciscan Legend.25

There was another important way in which Rendall influenced Clark. He would invite a dozen of the more interesting boys to join a society known as ‘SROGUS’, which stood for Shakespeare Reading Orpheus Glee United Society. They met on Saturday evenings, wearing dinner jackets, in the headmaster’s house, where Clark found himself alongside two future socialist grandees, Hugh Gaitskell and Richard Crossman. These readings cemented his lifelong taste for Shakespeare and the theatre, which one day would lead him to play a significant role in the formation of the National Theatre. The parts he asked to read show an interest in character: Justice Shallow, the porter in Macbeth, and Caliban.26

‘The beauty of the buildings of Winchester penetrated my spirit,’ Clark later wrote, and they inspired his lifelong love of architecture. He was bowled over by the cathedral: ‘nothing had prepared me for such a sequence of contrasting styles, each beautiful in itself, and yet palpably harmonious’.27 He later referred to it as the building he had in his mind during the war when he was put in charge of Home Publicity, and was formulating the values for which the country was fighting.28 Clark sketched the ruins of the Romanesque arches in the south transept – he was already aware of Turner – and was encouraged by the greatest architectural draughtsman of the day, Muirhead Bone, a kindly Scotsman who visited Winchester and would later play an important role in Clark’s life on the War Artists’ Advisory Committee. He also admired the fabric of the school itself, the Gothic chantry and its cloisters, and even the nineteenth-century buildings by William Butterfield. There is no doubt that Clark’s love of architecture was ignited at school, and from this later emerged his book The Gothic Revival and his acquisition of Saltwood Castle. It extended beyond the stones: ‘No Wykehamist can forget that Keats lived there while he was writing the Ode to Autumn, and walked every day through the meads to St. Cross: so his poem and letters are mixed up with the most vivid memories of natural beauty.’29 During the 1960s he was to campaign to save the water meadows.