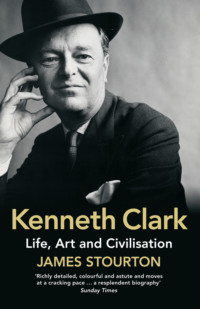

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation

Полная версия

Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilisation

Жанр: культура и искусствобиографии и мемуарыкинематограф / театризобразительное искусствотелевидение

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу