Полная версия

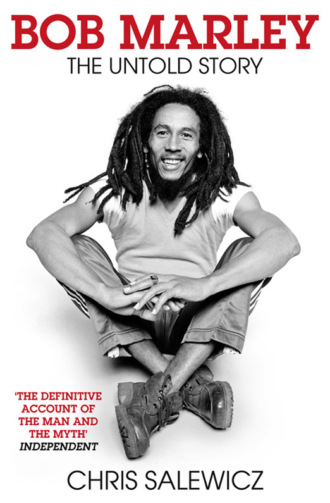

Bob Marley: The Untold Story

Still, Nesta was happy, running barefoot in the relatively car-free neighbourhood almost from when he could first walk. They would always say that Nesta loved to eat, and the boy was especially fond of his uncle Titus, who lived up by Yaya and always had plenty of surplus banana leaf or the spinach-like calaloo cooking on his stove. For a long time, Nesta’s eyes were bigger than his stomach. It became a joke in the area how he would take up a piece of yam, swallow his first piece and almost immediately fall asleep: ‘one piece just fill up his belly straightaway.’

Early on, there were signs that the child had been born with a poet’s understanding of life, an asset in a land like Jamaica, where metaphysical curiosities are a fact of life. When he was around four or five, Cedella would hear stories from relatives and neighbours that Nesta had claimed to read their palm. But she took it for a joke. How could this little boy of hers possibly do something like that? Though she did feel slightly shaken when she first heard that what Nesta told people about their futures invariably came true. There was District Constable Black from Stern Hill, for example: he told Cedella how the child had read his hand and everything he said had come to pass. Then a woman who had also had her palm looked at by Nesta confirmed this, forcing his mother to accept this strange talent of her jolly, much loved son, one that went a considerable way to defining him as an obeahman. ‘How he do things and prophesy things, he is not just by himself – he have higher powers, even from when he is a little boy,’ said Cedella Booker – as she later became. ‘The way I felt, the kind of vibes I get when Bob comes around … It’s too honourable. I always look upon him with great respect: there is something inside telling me that he is not only a son – there is something greater in this man. Bob is of a small stature, but when I hear him talk, he talk big. When it comes to the feelings and reactions I get from Bob, it was always too spiritual to even mention or talk about. Even from when he was a small child coming up.’

If Nesta had read his own palm and perceived what was to be the pattern of his life, he never told his mother. When he was almost five, however, Omeriah received a visit from Norval. What Cedella should do, he suggested, was to give up Nesta for adoption by Norval’s brother, the esteemed Robert, after whom he had been named. What was more, Cedella should guarantee that she would not attempt to see the boy any more. ‘It’s like he wouldn’t be my child no more! I said, “No way.”’

But then Norval came out to Nine Miles on another visit. He had had a different idea: what if the child were to come and stay with his father in Kingston for a time? He would pay for his education and let him benefit from all the opportunities and possibilities inherent in Norval’s own large, affluent family, who owned Marley and Co., Jamaica’s largest plant-hire company.

Cedella could see the advantages for her son in this. She felt she could go along with the plan. Nesta was duly delivered to her husband in Kingston. Hardly had the boy arrived, however, than he was taken downtown, to the house of a woman called Miss Grey. Norval Marley left his son with her, promising to return shortly. He never did.

All communication was then broken with the Malcolm family at Nine Miles. Cedella was deeply worried, fearing her son had been stolen from her – as indeed he had been. After almost a year, when Cedella had moved to Stepney, a village two or three miles past Nine Miles, a woman friend of hers went to Kingston to see her niece. The woman and her niece, who was called Merle, were together on the Spanish Town Road when they ran directly into Nesta. He had been sent to buy coal, he said, by the woman in whose house he was living. ‘Ask my mother,’ the boy continued, ‘why she don’t come look for me?’ And he told the woman his address.

When Cedella’s friend returned to Stepney that night she reported all that had happened. Nesta looked happy, she told Cedella: a little chubby, fat, healthy. A colossal sense of relief came over Cedella. ‘I was so tickled pink, I was so happy when she told me.’ But there was one problem: her friend had not had a pen or pencil with her. And she had forgotten the address where Nesta was living.

A solution was suggested – that Merle, the niece, might remember the address. Cedella wrote to her, and Merle replied straightaway that, although she couldn’t remember the number of the building, she knew Nesta was living on Heywood Street, in a poor downtown neighbourhood. Heywood Street was a short street, she added, and told Cedella that if she came up to Kingston, Merle would help her look for the missing child.

Accompanied by another friend from Nine Miles, Cedella arrived in Kingston one evening. Meeting Merle as arranged, Cedella discovered Heywood Street to be off Orange Street, and filled with stores. All these businesses were closed, however. Outside the first building that she came to, Cedella saw a man sitting out on the pavement. ‘I asked him,’ she said, using the name by which her son’s father called him, ‘if he knew a little boy who lived round there by the name of Robert Marley?’

‘Yeah mon,’ the man replied, looking behind him. ‘He was jus’ here a minute ago.’ Cedella’s heart lifted, as it filled with happiness.

Then she followed the man’s eyes. ‘There he was, just on the corner, playing. Nesta just bust right round: when he see it was me him just ran and hugged me so. And he said, “Mummy, you fatty.” I say, “Where you live?” He was very brisk, very bright. He say, “Right here. Her name is Mrs Grey: come and I’ll introduce you to her.”’

Mrs Grey was a heavyset woman. But she did not look at all well: she had lost almost all of her hair, and the skin peeled away in thin scales from both sides of her hands, one of the symptoms of ‘sugar’, as the widespread disease of diabetes is known in Jamaica; Mrs Grey also suffered from chronic high blood pressure. Robert, she told Cedella, had been her strength and guide, running errands for her, going to the market to fetch coal, as he had been on that day when he had been seen on the Spanish Town Road. He was going to school, Cedella discovered, though from what she heard it seemed as though his attendance was not regular. All the while, Mrs Grey said, she would find herself looking at Robert and wondering, ‘What happen to your mother? How is it that your mother never come to see you?’

‘I told her that I had to take him. And you could see how much she love him. She said she was going to miss him because he’s her right hand, to do any little thing for her. But she know that he have to leave. Then Nesta and I just go home. And we come back and everybody was glad to see him at his school, everybody.’

Once Nesta was back at school, however, he started to become very thin, suffering an inexplicable weight loss, as the extra pounds he had put on in Kingston mysteriously peeled away. On the advice of his teacher, Cedella began to feed the boy with a daily diet of goat’s milk. Whether it was that additional food supplement, or merely the healthier air and life he was living, he soon began not only to recover but to develop muscles and grow stronger and tougher, a country tough, that little-town soft gone.

That was the only occasion on which Cedella could remember sickness coming near her son. Not long after he returned to Nine Miles, however, he suffered a physical injury, perhaps a portent of a future problem. Running along the road one day, he stepped with his right foot on some slivers and splinters of broken glass, the remnants of a bottle. At first not all the glass could be dug out from the sole, hard and tough from years of barefoot walking. Then the wound wouldn’t heal up, pus seeping ceaselessly from it. When he tried to step on it, he would cry with pain, his foot going into involuntary spasms. Tears would well up in Cedella’s eyes as she watched her young son hobble up the rocky path to Yaya’s, trying to place his weight on the side of his foot. But it was not until several months had passed that his cousin Nathan, who was 13 years old, brought a potion, a yellow powder called Iodoform, from the chemist’s in Claremont; mixing it with sour orange he baked a poultice which finally healed Nesta’s foot. Nathan also made Nesta a guitar, constructed from bamboo and goatskin.

One more event of significance occurred shortly after Nesta returned from Kingston. When a woman asked him to read her palm, the boy shook his head. ‘No,’ said Nesta, ‘I’m not reading no more hand: I’m singing now.’

‘He had these two little sticks,’ Cedella recalled. ‘He started knocking them with his fists in this rhythmical way and singing this old Jamaican song:

Hey mister, won’t you touch me potato, Touch me yam, punking tomato? All you do is King Love, King Love, Ain’t you tired of squeeze up, squeeze up? Hey mister, won’t you touch me potato, Touch me yam, punking potato?

‘And it just made the woman feel so good, and she gave him two or three pennies. That was the first time he talked about music.’

During this time, Nesta was a pupil at the Stepney All Age School, in which he had first been enrolled when he was four, before he went to Kingston. His mother had continued to live in Stepney when she brought him back from the capital. Cedella had set up a small grocery shop there, building most of it herself, carrying the mortar and grout. When it was set up Nesta would help her in it when he returned from school. Its stock was never more than the neighbourhood market would bear: bread, flour, rice, soft drinks, which she used to collect on a donkey carrying a hamper. One day as she was walking along the road, the donkey’s rope held loosely in her hand, the animal reared up on its hind legs and ran down a hill, mashing up all the bottles it was carrying. Cedella cried and cried and cried, and was only somewhat mollified when people who had witnessed the incident assured her they had also seen the cause of it, a spirit that had come from Murray Mountain to frighten the beast. But it set Cedella to thinking: wasn’t there perhaps an easier way of ensuring some small measure of prosperity for her and her pickney?

There was another new shopkeeper in the area: at Nine Miles, a man from Kingston called Mr Thaddius ‘Toddy’ Livingston had also opened up a small grocery shop. The man had a wife and a child, who had been christened Neville but was more popularly called Bunny. The boy had been born on 10 April 1947, and was also a pupil at Stepney All Age School. He and Bob became friends. Cedella, however, was only on nodding acquaintanceship with her business rival, Bunny’s father. After a time, Mr Toddy sold up his business and moved back to Kingston, intending to open a rum bar.

Soon Cedella made a similar decision, and a relative bought her shop from her. She was now in her mid-twenties and becoming restless. Though she deeply loved her son, she felt her life was slipping away in Nine Miles. More and more, she had begun travelling to Kingston, taking jobs as a domestic help and leaving Nesta in the care of her father, Omeriah, who bore a deep love for the boy and was happy to care for him.

Omeriah Malcolm, a disciplinarian and a very hard worker, set Nesta Robert Marley to work chopping wood, caring for and milking the cows, grooming horses, mules, and donkeys and dressing their sores, chasing down goats, and feeding the pigs. To an extent Nesta ran free and wild. Unusually for a rural Jamaican family, little attention was paid to sending him to church – although a Christian, Omeriah Malcolm took an extremely free-thinking view of the necessity of regular church worship. Years later, Bob would talk of his farmer grandfather as someone who had really cared for him, perhaps the only person who had really cared for him at that time – his mother’s absences in Kingston rankled with him.

Inevitably, Nesta also began to osmose some of the arcane knowledge to which his grandfather was privy. Another relative, Clarence Malcolm, had been a celebrated Jamaican guitarist, playing in dancehalls during the 1940s. Learning of Nesta’s interest in music, Clarence would spend time with the boy, letting him get the feel of his guitar. He was delighted when the boy won a pound for singing in a talent contest held at Fig Tree Corner on Fig Tree Road, on the way to the junction that leads to Stepney and Alderton. So began a pattern of older wise men taking a mentor-like role in the life of the essentially fatherless Nesta Robert Marley, a syndrome that would continue for all his time on earth.

From Nine Miles, Nesta would walk the two and a half miles to school at Stepney, dressed in the freshly pressed khaki shirt and pants that comprise the school uniform of Jamaican boys. The journey was not considered excessive – some children walked to the school from as far away as Prickle Pole, seven miles distant.

When he was ten, his teacher was a woman called Clarice Bushay; she taught most subjects to the sixty or so children in her overcrowded but well-disciplined class, which was divided only by a blackboard from the four or five other classes in the vast hall that formed the school. Away from his family circle, Nesta didn’t reveal the cheerful countenance he presented in Nine Miles, where his wry and knowing smile was rarely absent.

Hidden behind a mask of timidity, his potential was not immediately apparent to Miss Bushay. When, however, she realised that this particular pupil required constant reassurance, needing always to be told that his work was satisfactory, he began to blossom. ‘As he was shy, if he was not certain he was right, he wouldn’t always try. In fact, he hated to get answers wrong, so sometimes you’d have to really draw the answer out of him. And then give him a clap – he liked that, the attention.’

She did, though, feel a need to temper the amount of concentration she could give him. ‘Because he was light-skin, other children would become jealous of him getting so much of my time. I imagined he must have been very much a mother’s pet, because he would only do well if you gave him large amounts of attention. But it was obvious he had a lot of potential.’ The difficulties endured by Nesta Robert Marley because of his mixed-race heritage were representative of an archetypal Jamaican problem: since independence from colonial rule, the national motto has been ‘Out of many, one people’, but this aphorism masks a complex reality in which shadings of skin colour create prejudices on all sides. The truth was that, as a child, the future Bob Marley was a distinct outsider, the quintessential ugly ducking. Bob felt from the start that he wasn’t wanted by either race, and he knew he had to survive, and become tough.

Even at Stepney All Age School, Nesta was confirmed in his extracurricular interests. After running down to the food vendors by the school gates at lunch-time to buy fried dumplings or banana, or fish fritters and lemonade, it would be football – with oranges or grapefruits used as balls – and music with which he busied himself for the rest of the break. But he was so soft-spoken when he sang – a further sign of an acute lack of self-confidence – that you would have to put your ear down almost to his mouth to hear that fine alto voice. Yet of all the children who attempted to construct guitars from sardine tins and bamboo, it would always be Nesta who contrived to have the best sound. ‘He was very enterprising: you had to commend him on the guitars he made.’

He was a popular boy, with very many friends; very loving, but clearly needing to get back as much love as he gave out. ‘When he came by you to your desk,’ Miss Bushay noted, ‘you knew he just wanted to be touched and held. It seemed like a natural thing with him – what he was used to. A loving boy, and really quite soft.’ An obedient pupil, he deeply resented the occasion that he was flogged by the principal for the consistently late arrival at school by himself and the other children from Nine Miles. After the beating, falling back on his grandfather’s secret world, he was heard to mutter dark threats about the power of a cowrie shell he possessed and what he planned to do with it to the principal.

Maths was Nesta’s best subject, whilst his exceptionally retentive memory allowed him unfailing success in general knowledge. But Miss Bushay would have to encourage him to open reading books: she noticed that, although he’d read all his set texts, he wouldn’t borrow further volumes, as did some of his classmates. ‘He seemed to spend more time with this football business.’

One day, whilst she was in Kingston, his mother received a telegram from Nine Miles, telling her that Nesta had cut open his right knee and been taken to the doctor to have the wound stitched. When she next saw her son, he told her what had happened. Running from another boy at the back of a house, he had raced round a corner, directly into an open coffin. Startled, he had spun away, cutting his knee on a tree stump. ‘I sometimes wonder,’ said his mother, ‘with his gift of second sight, did Nesta glimpse something that day in the gaping coffin that made him fly out of that backyard in breakneck terror? What might he have seen that day?’

When Nesta was 11 years old, there was another accident. Playing in a stream to which his mother had forbidden him to go, he badly stubbed the big toe of his right foot, cutting it open. It was not until it became almost gangrenous that he told his mother, who then wrapped it in herbs to take down the inflammation and remove the poison. But from then on, that toe was always black.

Whilst his mother was in the capital, Nesta for a time was lodged with his aunt Amy, his mother’s sister, who lived in the hamlet of Alderton, some eight miles from Ocho Rios, on the north coast. The aunt, Rita Marley later observed, was something of a ‘slave-driver’, a strict disciplinarian even by Jamaica’s harsh standards. At five in the morning the boy would be woken up to do yard work: he would have to tie up and milk the goats and walk miles for fresh water before going to the local school, which he could see from his aunt’s house. The only respite from his chores was the friendship of his cousin Sledger, Amy’s son; the pair rebelled together against her regime, earning a reputation with Amy as troublemakers. One day Nesta’s mother received a message: Nesta had run away from his aunt’s, carrying his belongings, and made his way back to Nine Miles. In fact, he was fleeing punishment because he and Sledger had been left behind to make the Sunday ‘yard’ lunch but, clearly enthralled with their task, had then eaten up almost all of it before Amy returned from church.

However, Nesta’s mother Cedella was also a naughty girl. One Sunday evening when Cedella was about to set off back to Kingston after a weekend with her family, she got a lift in the same car as Toddy Livingston, who had returned to Nine Miles to visit some friends. It was the first extensive period of time they had spent together and there was a strong mutual attraction. On their return to Kingston they started dating and, notwithstanding Toddy’s married status, became lovers.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.