Полная версия

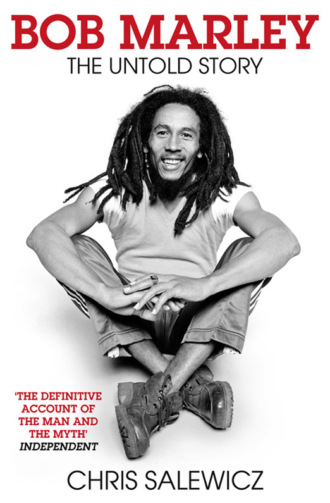

Bob Marley: The Untold Story

BOB MARLEY THE UNTOLD STORY

CHRIS SALEWICZ

Dedication

For Dickie Jobson (14 November 1941–25 December 2008)

and Rob Partridge (2 June 1948–26 November 2008)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Introduction

Jamaica

Natural Mystic

Kingston

Trench Town Rock

Nice Time

Duppy Conqueror

The Rod of Correction

Catch a Fire

Natty Dread

Rastaman Vibration

Exodus

Peace Concert

Uprising

Zimbabwe

Legend

Plates

Sources

Index

Acknowledgements

Other Works

Praise for Chris Salewicz’s Redemption Song

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

Introduction

ME ONLY HAVE ONE AMBITION, Y’KNOW. I ONLY HAVE ONE THING I REALLY LIKE TO SEE HAPPEN. I LIKE TO SEE MANKIND LIVE TOGETHER – BLACK, WHITE, CHINESE, EVERYONE – THAT’S ALL.

In early 1978 I spent two months in Jamaica, researching its music and interviewing many key figures, having arrived there on the same reggae-fanatics’ pilgrimage as John ‘Johnny Rotten’ Lydon and Don Letts, the Rastafarian film-maker. My first visit to the island was a life-changing experience, and I plunged into the land of magic realism that is Jamaica, an island that can be simultaneously heaven and hell. Almost exactly a year later, in February 1979, I flew to Kingston on my second visit to ‘the fairest land that eyes have beheld’, according to its discoverer, Christopher Columbus, who first sighted the ‘isle of springs’ in 1494. Arriving late in the evening, I took a taxi to Knutsford Boulevard in New Kingston and checked into the Sheraton Hotel.

Jet lag meant that I woke early the next morning. Seizing the time, I found myself in a taxi at around quarter to eight, chugging through the rush-hour traffic, rounding the corner by the stately Devon House, the former residence of the British governor, and into and up Hope Road. ‘Bob Marley gets up early,’ I had been advised.

Arriving at his headquarters of 56 Hope Road, trundling through the gates and disgorging myself from my Morris Oxford cab in front of the house, there was little sign of activity. On the wooden verandah to the right of the building was a group of what looked like tough ghetto youth, to whom I nodded greetings, searching in vain for any faces I recognised. In front of the Tuff Gong record shop to the right of the house was a woman who wore her dreadlocks tucked into a tam; she was sweeping the shop’s steps with a besom broom that scurried around the floor-length hem of her skirt. A sno-cone spliff dangled from her mouth. Wandering over to her, I introduced myself, mentioning that I had been in Jamaica the previous year writing about reggae, showing her a copy of the main article I had written in the NME. She was extremely articulate, and I discovered that her name was Diane Jobson and that she was the inhouse lawyer for the Tuff Gong operation (over the years I was to get to know her well; and her brother Dickie, who directed the film Countryman, became a close pal).

Then a 5 Series BMW purred into the yard. Driven by a beautiful girl, it had – like many Jamaican cars – black-tinted windows and an Ethiopian flag fluttering in the breeze from an aerial on its left front wing. Out of it stepped Bob Marley. He greeted the ghetto youth, walked towards them, and began speaking with them. On his way over, he registered my presence. After a couple of minutes, I walked towards him. I introduced myself, and he shook hands with me with a smile, paying attention, I noticed, to the Animal Rights badge that by chance I was wearing on my red Fred Perry shirt; again, I explained I had been to Jamaica for the first time the previous year, and showed him the article. He seemed genuinely interested and began to read it. As he did so, like Bob Marley should have done, he handed me a spliff he had just finished rolling. Nervously, I took it and pulled away.

After a minute or two Diane came over. Gathering together the youth, she led them in the direction of a mini-bus parked in the shade that I had not previously noticed. Bob made his excuses – ‘We have to go somewhere’ – and walked over to the vehicle. Then, as he stepped into it, he turned. ‘Come on, come with us,’ he waved with a grin, climbing down out of the vehicle and holding the door open for me.

I hurried over. Ushering me into the mini-bus, Bob squeezed up next to me on one of its narrow two-person bench-seats, his leg resting against my own. I tried to disguise my feelings – a sense of great honour as well as slight apprehension that the herb I had smoked was beginning to kick in, suddenly seeming a million times stronger than anything I had ever smoked in London. I was starting to feel rather distanced from everything, which was possibly just as well. Bumping through the potholed backstreets of what I knew to be the affluent uptown suburb of Beverly Hills, I ventured to ask Bob, who was himself hitting on a spliff, where we were going. ‘Gun Court,’ he uttered, matter-of-factly.

I blinked, and tried quickly to recover myself. The Gun Court had a reputation that was fearsome. To all intents and purposes, the place was a concentration camp – certainly it had been built to look like one: gun towers, barbed-wire perimeters, visibly armed guards, a harsh, militaristic feel immediately apparent to all who drove past its location on South Camp Road. The Gun Court was a product of Michael Manley’s Emergency Powers Act of 1975. Into it was dumped, for indefinite detention or execution after a summary trial, anyone in Jamaica found with any part of a gun. (In more recent times, it is said, the security forces adopt a more cost-effective and immediate solution: anyone in Jamaica found with any part of a gun, runs the myth, is executed on the spot – hence the almost daily newspaper reports of gunmen ‘dying on the way to hospital’ …) The previous year, when I had been in Kingston with Lydon, Letts and co., the dreadlocked Rastafarian filmmaker had been held at gunpoint by a Jamaica Defence Force soldier whilst filming the exterior of the Gun Court. At first the squaddie refused to believe Letts was British; only after being shown his UK passport did he let him walk away. What would have happened had he been Jamaican?

‘Why are we going there?’ I demanded of Bob, as casually as I could.

‘To see about a youth them lock up – Michael Bernard,’ he quietly replied.

Michael Bernard, I learned later, was a cause célèbre.

Having descended from the heights of Beverly Hills, a detour that had been taken to avoid morning traffic (like most of the rest of the world, and especially in Jamaica at that time, when cars and car parts were at a considerable premium, this was nothing compared to the almost permanent gridlock that Kingston was to become by the end of the century), we were soon pulling up outside the Gun Court’s sinister compound.

At nine in the morning, beneath an already scorching tropical sun, the vision of the Gun Court was like a surreal dubbed-up inversion of one of the ugly, incongruous industrial trading estate-type buildings that litter much of Kingston’s often quite cute sprawl.

At the sight of Bob emerging from the mini-bus, a door within the main gates opened for his party. We stepped through into the prison. After standing for some time in the heat of the forecourt yard, an officer appeared. In hushed tones he spoke to Bob; I was unable to hear what passed between them, which was probably just as well – it being almost a year since I had last enjoyed a regular daily diet of patois, I was beginning to register I could comprehend only about a half of what was being said around me.

Then we were led into the piss-stinking prison building itself. And through a number of locked, barred doors, and into the governor’s broad office, like the study of a boarding-school headmaster, which was also the demeanour of the governor himself, a greying, late-middle-aged man who sat behind a sturdy desk by the window. We were seated on hard wooden chairs in a semicircle in front of him. I found myself directly to the right of Bob, who in turn was seated nearest to the governor. Through a door in the opposite wall arrived a slight man who appeared to be in his early twenties. He was shown to a chair. This was Michael Bernard, who had been sentenced for an alleged politically motivated shooting, one for which no one I met in Kingston believed him to be responsible.

Discussions now began, the essence of which concerned questions by Bob as to the possibilities of a retrial or of Bernard’s release from prison. Bernard said virtually nothing, and almost all speech was confined to Bob and the governor. I asked a couple of questions, but when I interrupted a third time Bob wisely hushed me – I was starting to get into a slightly right-on stride here. Most of the dialogue, I noted, was conducted in timorous, highly reverent tones by all parties present, almost with a measure of deference, or perhaps simply hesitant nervousness. (Over the years I was to decide that it was the latter, noting that often Jamaicans called upon to speak publicly – whether rankin’ politicians at barnstorming rallies, Rasta elders at revered Nyabinghi reasonings, Commissioner of Police Joe Williams in an interview I conducted with him, or crucial defence witnesses in the rarified, bewigged atmosphere of English courts – would present themselves with all the stumbling hesitancy and lack of rigorous logic of a very reluctant school-speechday orator. Yet in more lateral philosophical musings and reasonings, there are few individuals as fascinatingly, confidently loquacious as Jamaicans when it comes to conversational elliptical twists, stream-of-consciousness free-associations, and Barthes-like word de- and re-constructions.)

After twenty or so minutes, all talk seemed to grind to a halt. Afterwards I was left a little unclear as to what conclusions had been arrived at, if any. At first I worried that this was because initially I had been struggling with the effects of the herb, which seemed like a succession of psychic tidal-waves. Then later I realised that the purpose of this mission to the Gun Court was simply to show that Michael Bernard had not been forgotten.

Bidding farewell to the prisoner, wishing him luck, and thanking the governor for his time, we left his office, clanking out through the jail doors and into the biting sunlight. Soon we were back at 56 Hope Road, which by then had become a medina of all manner of activity. ‘Stick around,’ said Bob. I did. And on a bench in the shade of a mango tree round the back of the house promptly fell asleep for at least two hours from what was probably a combination of jet lag, the spliff, and some kind of delayed shock.

This visit to the Gun Court with Bob Marley was one of the great experiences of my life. I was in Jamaica for another three weeks or so. During that time I saw Bob several more times. I watched rehearsals at 56 Hope Road; saw Bob playing with some of his kids – the ones that had just released their first record as the Melody Makers; and found him with one of the most gorgeous women who had ever crossed my eyes (a different one from the car-driver at 56 Hope Road) at a Twelve Tribes Grounation (essentially, dances steeped in the mystique of Rastafari) one Saturday night on the edge of the hills. She turned out to be Cindy Breakspeare, Jamaica’s former Miss World. I also interviewed Bob for an article: whilst doing so, I remember feeling a measure of guilt for taking up so much of his precious time – though I didn’t realise then precisely quite how precious and finite it was. Part of the reason I thought this was because I felt Bob looked terribly tired and strained – it was only just over eighteen months later that he collapsed whilst jogging in Central Park with his friend Skill Cole, and was diagnosed as suffering from cancer.

It came as a deep, unpleasant shock just before midnight on 11 May 1981 to receive a phone call from Rob Partridge, who had so assiduously handled Bob’s publicity for Island Records, to be told that Bob had lost his fight with cancer and passed on. (I had always believed that Bob would beat the disease …) Although I wrote his obituary for NME, it seemed my relationship with Bob and his music was only just beginning. In February 1983, I was back in Jamaica, writing a story for The Face about Island’s release of the posthumous Bob Marley album Confrontation.

Again, jet lag caused me to wake early on the first morning I was there. This time I was staying just down the road from the former Sheraton, at the neighbouring Pegasus Hotel. Getting out of bed, I switched on the radio in my room. The Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation (JBC) seven o’clock news came on with its first story: ‘Released from the Gun Court today is Michael Bernard …’ Wow! Phew! JAH RASTAFARI!!! That Jamaica will get you every time. The island really is a land of magic realism, a physical, geographical place that is like a manifestation of the collective unconscious. Or is it that Bob Marley, as someone once suggested to me, is very active in psychic spheres and has a great sense of humour? Was this just something he’d laid on for me in the Cosmic Theme Park of the Island of Springs, I found myself wondering, with a certain vanity.

JAMAICA

The Caribbean island of Jamaica has had an impact on the rest of the world that is far greater than might be expected from a country with a population of under three million. Jamaica’s history, in fact, shows that ever since its discovery by Christopher Columbus, it has had a disproportionate effect on the rest of the world.

In the seventeenth century, for example, Jamaica was the world centre of piracy. From its capital of Port Royal, buccaneers under the leadership of Captain Henry Morgan plundered the Spanish Main, bringing such riches to the island that it became as wealthy as any of Europe’s leading trading centres; the pleasures such money brought earned Port Royal the reputation of ‘wickedest city in the world’. In 1692, four years after Morgan’s death, Port Royal disappeared into the Caribbean in an earthquake. However, a piratic, rebellious spirit has been central to the attitude of Jamaicans ever since: this is clear in the lives of Nanny, the woman who led a successful slave revolt against the English in 1738; of Marcus Garvey, who in the 1920s became the first prophet of black self-determination and founded the Black Star shipping line, intended to transport descendants of slaves back to Africa; of Bob Marley, the Third World’s first superstar, with his musical gospel of love and global unity.

Jamaica was known by its original settlers, the Arawak peoples, as the Island of Springs. It is in the omnipresent high country that resides Jamaica’s unconscious: the primal Blue Mountains and hills are the repository of most of Jamaica’s legends, a dreamlike landscape that furnishes ample material for an arcane mythology.

On the north side of the Blue Mountains, in the parish of Portland, one of the most beautiful parts of Jamaica, is Moore Town. It was to the safety of the impenetrable hills that bands of former slaves fled, after they were freed and armed by the Spanish, to harass the English when they seized the island in 1655. The Maroons, as they became known, founded a community and underground state that would fight a guerrilla war against the English settlers on and off for nearly eighty years.

When peace was eventually established, the Maroons were granted semi-autonomous territory both in Portland and Trelawny, to the west of the island. In Moore Town was buried the great Maroon queen, Nanny, who led her people in battles in which they defeated the English redcoats. Honoured today as a National Hero of Jamaica, Nanny’s myth was so great that she was said to have the ability to catch musket-balls fired at her – in her ‘pum-pum’, according to some accounts.

Jamaica has always been tough. The Arawak peoples repulsed invasions by the cannibalistic Caribs who had taken over most of the neighbouring islands. Jamaica was an Arawak island when it was discovered in 1494. ‘The fairest island that eyes have beheld; mountainous and the land seems to touch the sky,’ wrote Columbus. Although he may not have felt the same nine years later, on his fourth voyage to the New World. In St Ann’s Bay, later the birthplace of Marcus Garvey, Columbus was driven ashore by a storm, and his rotting vessels filled with water almost up to their decks as they settled on the sand of the sea-bed.

Later placed into slavery by the Spaniards, the Arawaks were shockingly abused, and many committed suicide. Some were tortured to death in the name of sport. By 1655, when the English captured the island, the Arawaks had been completely wiped out.

Even after the 1692 earthquake, piracy remained such a powerful force in the region that a King’s pardon was offered in 1717 to all who would give up the trade. Many did not accept these terms, and in November 1720 a naval sloop came across the vessel of the notorious pirate ‘Calico Jack’ Rackham anchored off Negril, in the west of Jamaica. Once the crew was overpowered – with ease: they were suffering from the effects of a rum party – two of the toughest members of Rackham’s team were discovered to be women disguised as men: Anne Bonny and Mary Read, who each cheated the gallows through pregnancy.

Those Jamaican settlers who wished to trade legally could also make fortunes. Sugar, which had been brought to the New World by Columbus on the voyage during which he discovered Jamaica, was the most profitable crop that could be grown on the island, and it was because of their importance as sugar-producing islands that the British West Indies had far more political influence with the English government than all the thirteen American mainland colonies.

Sugar farming requires a significant labour force, and it was this that led to the large-scale importation of African slaves. For the remainder of the eighteenth century, the wealth of Jamaica was secured with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession: one of its terms was that Jamaica became the distribution centre for slaves for the entire New World. The first slaves shipped to the West Indies had been prisoners of war or criminals, purchased from African chiefs in exchange for European goods. With a much larger supply needed, raiding parties, often under the subterfuge of engaging in tribal wars, took place all along the west coast of Africa. The horrors of the middle passage had to be endured before the slaves were auctioned, £50 being the average price.

Although the money that could be earned was considerable compensation for the white settlers, life in Jamaica was often a worry. There were slave revolts and tropical diseases. War broke out frequently, and the island was then threatened with attack by the French or the Spanish – Horatio Nelson, when still a midshipman, was stationed on the island. Hurricanes, which invariably levelled the crop, were not infrequent; and earthquakes not unknown. In the late seventeenth century Kingston harbour was infested with crocodiles, but it should be said that in those days inhabitants of the entire south coast of the island always ran the risk of being devoured by them.

Despite such disadvantages, it has always been hard for Jamaica not to touch the hearts of visitors, with its spectacular, moody beauty. The island contains a far larger variety of vegetation and plantlife than almost anywhere in the world (as it is located near the centre of the Caribbean sea, birds carrying seeds in their droppings fly to it from North, Central, and South America). Jamaica’s British colonisers added to this wealth of vegetation, often whilst searching for fresh, cheap means of filling the bellies of its slaves. The now omnipresent mango, for example, was brought from West Africa and it was on a journey across the Pacific to bring the first breadfruit plants to Jamaica that the mutiny on the Bounty took place.

Slavery was eventually abolished in 1838. From the 1860s, indentured labour from India and China was imported; the Indians brought with them their propensity for smoking ganja, itself an Indian word (interestingly, sometimes spelt ‘gunjah’), as well as the plant’s seeds. In the 1880s, a new period of prosperity began after a crop was found to replace sugarcane – the banana. In 1907, however, this new prosperity was partially unhinged by the devastating earthquake that destroyed much of Kingston. The economy recovered, and the next wave of financial problems occurred in the late 1930s, as the worldwide depression finally hit the island. A consequence of this was the founding of the two political parties, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) under Alexander Bustamante and the People’s National Party (PNP) under Norman Manley, which would spearhead the path towards independence in 1962.

On 6 August 1962 Jamaica became an independent nation. The Union Jack was lowered and the green, gold, and black standard of Jamaica was raised. Three months previously, the JLP had won a twenty-six-seat majority and taken over the government under Prime Minister Bustamante. Paradox is one of the yardsticks of Jamaica, and it should be no surprise that the Jamaica Labour Party has always been far to the right of its main opposition, the People’s National Party.

Beneath this facade of democracy, the life of the ‘sufferah’, downcast in his west Kingston ghetto tenement, was essentially unchanged. In some ways things were now more difficult. The jockeying for position created by self-government brought out the worst in people. Soon the MPs of each of the ghetto constituencies had surrounded themselves with gun-toting sycophants anxious to preserve their and their family’s position. In part this was a spin-off from the gangs of enforcers that grew up around sound systems: back the wrong candidate in a Jamaican election and you can lose not only your means of livelihood, but also your home – and even your life. Political patronage is the ruling principle in Jamaica.

During the 1960s, Jamaican youth, who felt especially disenfranchised, sought refuge in the rude-boy movement, an extreme precursor of the teenage tribes surfacing throughout the world. Dressed in narrow-brimmed hats and the kind of mohair fabrics worn by American soul singers, rude boys were fond of stashing lethal ‘ratchet’ knives on their persons, and bloody gang fights were common. Independence for Jamaica coincided with the birth of its music business; in quick succession, ska, rock steady, and then reggae music were born, the records often being used as a kind of bush telegraph to broadcast news of some latest police oppression that the Daily Gleaner would not print.

In 1972, after ten years in power, the JLP was voted out of office. Michael Manley’s People’s National Party was to run Jamaica for the next eight years. Unfortunately, Manley’s efforts to ally with other socialist Third World countries brought the wrath of the United States upon Jamaica, especially after the prime minister nationalised his country’s bauxite industry, which provides the raw material for aluminium – and had been previously licensed to the Canadian conglomerate Alcan.