Полная версия

Sextant: A Voyage Guided by the Stars and the Men Who Mapped the World’s Oceans

There are many kinds of sextant, and they come in many different sizes – from pocket ones just a few inches across to heavyweight models on a much grander scale. And many materials have been employed in making them, from brass and steel to plastic and even cardboard. The essential design, however, has varied little since the eighteenth century, and a good sextant has the reassuring heft and feel of something really well made. With familiarity comes the recognition that this is an instrument perfectly adapted to its purpose: a solution to a practical problem so elegant and efficient as to be quite simply beautiful. But although I had studied a diagram, the sextant now in my hands was bafflingly unfamiliar. Attached to a triangular black steel frame with a wooden handle on one side were two mirrors, several dark shades, a small telescope and an index arm with a micrometer drum that swung along a silvered arc marked in degrees. Colin showed me how to hold it, with the handle in my right hand and my eye to the telescope.

I had to measure the height of the sun above the horizon just as it reached its highest point in the sky due south of us – as it crossed our meridian. Colin first adjusted the shades on the sextant, then, looking through the telescope, moved the index arm until the sun’s lower edge (or ‘limb’, in astronomical jargon) was more or less on the horizon. I then took his place in the main hatch, braced against the slow roll of the boat, and, gripping the handle firmly, peered tentatively through the telescope at the southern horizon.

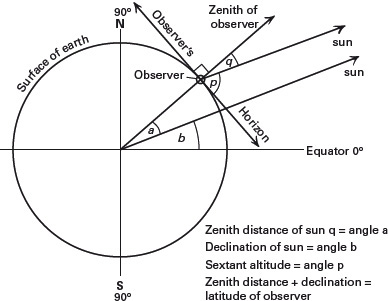

Fig 1: Principles of the Meridian Altitude

All I could see at first was a circle divided vertically between a light half and a dark: the left-hand side was the direct view through the plain glass side of the horizon mirror, and the darker right-hand side was the reflected view of the sky above us through the heavily shaded index mirror. Then I found the horizon and, scanning to left and right, caught a glimpse of a brilliant white disc floating just above the dark line of the sea. In a moment it had gone, but then I caught and held it, fascinated to see it moving steadily upwards, the gap between the disc and the horizon widening all the time. It was the sun and I was watching the earth turn.

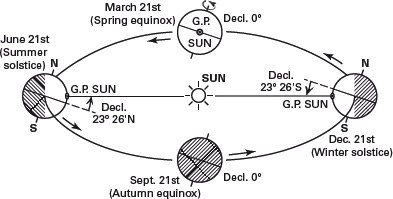

Fig 2: Diagram illustrating the sun’s varying declination. (G.P. is the geographical position: see Glossary.)

If I rocked the sextant from side to side, the sun swung in an arc across the sky. By adjusting the micrometer, I brought the disc slowly down until, when the sextant was held vertically, its lower limb was just kissing the horizon. The sun was still moving upwards, but much more slowly now as it neared our meridian. After a minute or two, the white disc paused at the top of its arc. Taking the sextant away from my eye, I looked at the scale and read off the angle: 64° on the main scale and 41 (60 minutes to one degree) on the micrometer. This was the sun’s meridian altitude, or ‘mer alt’.

Colin took the sacred instrument from me and confirmed the reading. I looked up the sun’s declination in the Nautical Almanac and made a few corrections to the observed angle. In a few minutes, to my astonished delight, I completed the simple addition and subtraction sums that yielded our latitude.6 We were somewhere on the parallel of 43° 17' North, and – as Colin observed – I was now as well equipped to find my way safely across an ocean as any European mariner before the time of Captain Cook.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.