Полная версия

Sextant: A Voyage Guided by the Stars and the Men Who Mapped the World’s Oceans

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2014

Copyright © David Barrie 2014

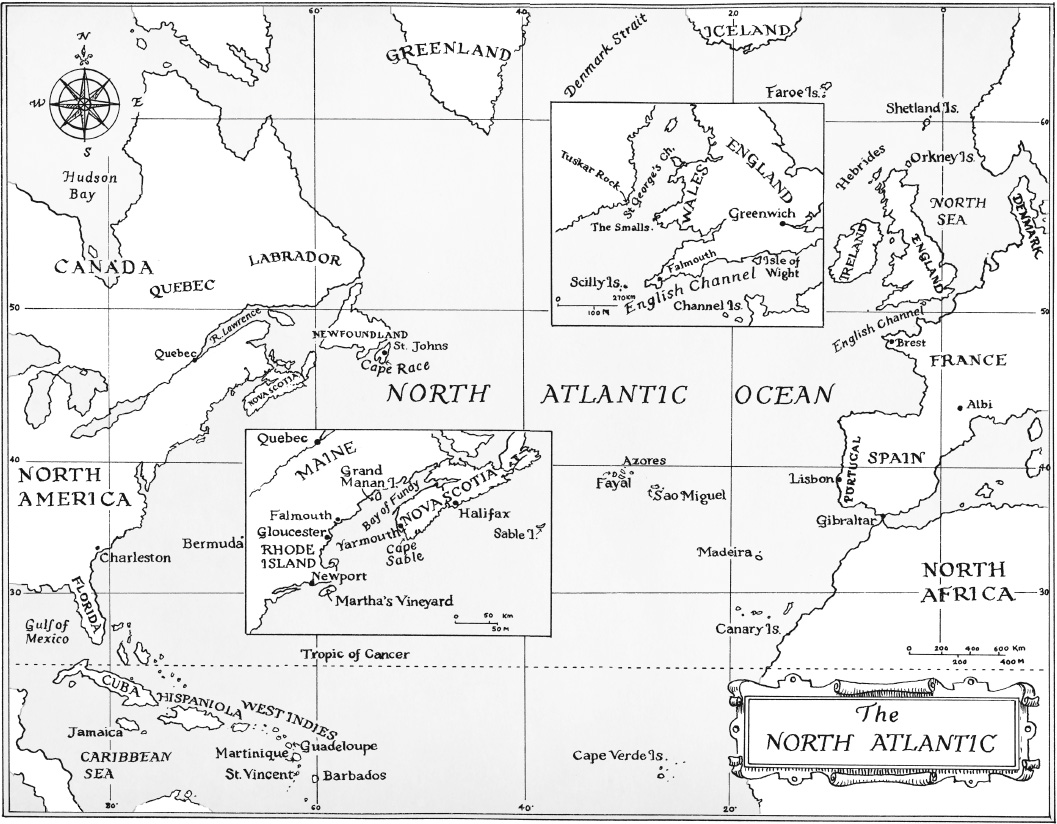

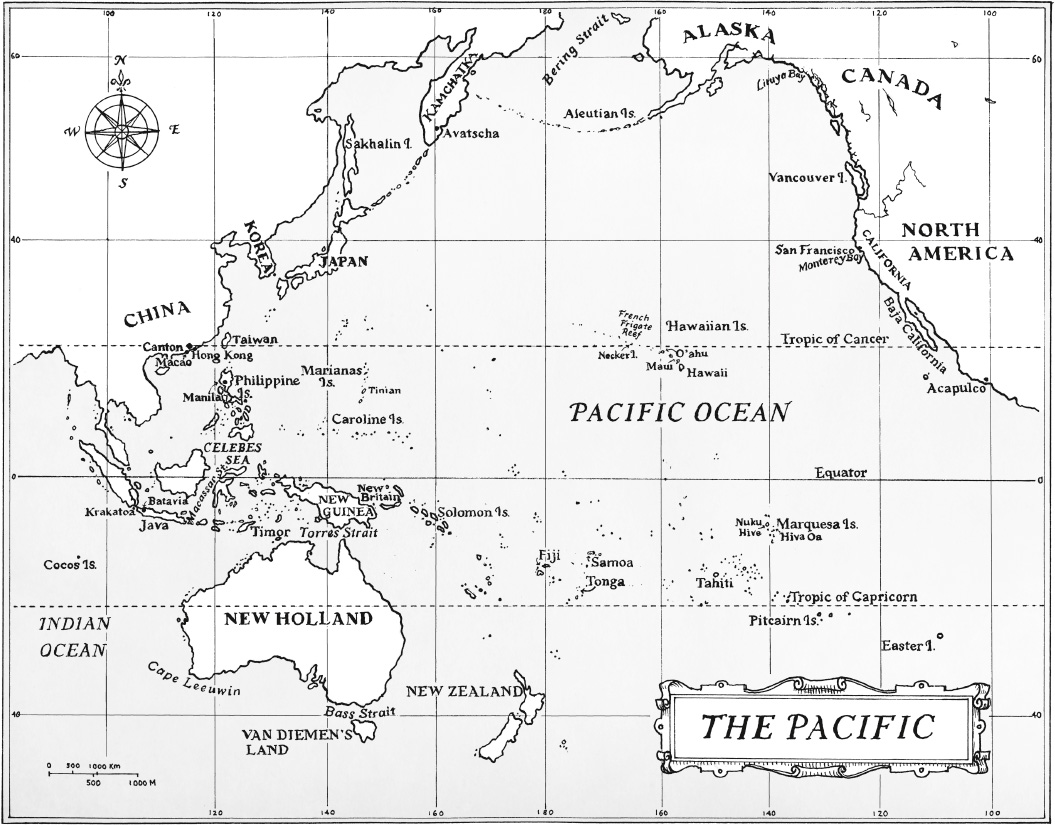

Maps © Nicolette Caven

David Barrie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007516568

Ebook Edition 2014 ISBN: 9780007516575

Version: 2015-05-16

Dedication

To the memory of my father, Alexander Ogilvy Barrie (1910–1969), who first showed me the stars, and of Colin McMullen (1907–1991), who taught me to steer by them.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Preface

Chapter 1: Setting Sail

Chapter 2: First Sight

Chapter 3: The Origins of the Sextant

Chapter 4: Bligh’s Boat Journey

Chapter 5: Anson’s Ordeals

Chapter 6: The Marine Chronometer

Chapter 7: Celestial Timekeeping

Chapter 8: Captain Cook Charts the Pacific

Chapter 9: Bougainville in the South Seas

Chapter 10: La Pérouse Vanishes

Chapter 11: The Travails of George Vancouver

Chapter 12: Flinders – Coasting Australia

Chapter 13: Flinders – Shipwreck and Captivity

Chapter 14: Voyages of the Beagle

Chapter 15: Slocum Circles the World

Chapter 16: Endurance

Chapter 17: ‘These are men’

Chapter 18: Two Landfalls

Epilogue

Picture Section

Footnotes

Notes

List of Illustrations

Bibliography

Glossary of Technical Terms

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Preface

Crossing an ocean under sail today is not an especially risky undertaking. Accurate offshore navigation – for so long an impossible dream – has now been reduced to the press of a button, and most modern yachts are strong enough to survive all but the most extreme weather. Even if errors, accidents or hurricanes should put a boat in danger, radio communications give the crew a good chance of being rescued. Few sailors now lose their lives on the open ocean: crowded inshore waters where the risk of collision is high are far more hazardous.

But it was not always so. When a young man called Álvaro de Mendaña set sail from Peru in November 1567 to cross the Pacific with two small ships, accompanied by 150 sailors and soldiers and four Franciscan friars, he faced difficulties so great that his chances of survival, let alone achieving his objectives, were slim.1

Mendaña’s orders from his uncle, the Spanish Viceroy, were to convert any ‘infidels’ he encountered to Christianity, but the expedition was certainly not motivated entirely by religious zeal. According to Inca legend great riches lay on islands somewhere to the west. Were these islands perhaps outliers of the great southern continent that was believed to lie hidden somewhere in the unexplored South Seas? Mendaña, who was twenty-five, hoped to find the answer, to set up a new Spanish colony, to make his fortune and win glory. However, any optimism he may have felt as the coast of Peru dipped below the horizon would have been misplaced. Although Magellan had managed to cross the Pacific from east to west in 1520–1, he had been killed in fighting with local people after reaching the Philippines, and only four out of the forty-four men who sailed with him aboard his small flagship had returned safely to Spain.2 This first, epic circumnavigation was counted as a brilliant success, but other expeditions ended in oblivion.

The challenges Mendaña faced were many. Not only was it impossible to carry sufficient fresh food and water for a voyage that might well last several months, but sailing ships were also vulnerable to the stress of weather, and the discipline of their rough and uneducated crews could never be relied on. First encounters with native peoples were fraught with danger, even if both sides were keen to avoid conflict, not least because cultural and linguistic differences made communication so difficult. If the Europeans brought with them infectious diseases that were to devastate native populations, tropical diseases also posed a serious threat to the visitors. To venture into the unexplored wastes of the Pacific was therefore to risk shipwreck, mutiny, warfare, disease, thirst, hunger and, most insidious of all, malnutrition.

After a passage of eighty days Mendaña’s two ships at last reached the ‘Western Islands’ in February 1568. Thinking at first that they had indeed found the legendary southern continent, Mendaña and his men explored the high, jungle-clad island on which they first landed and soon realized their mistake. They named it Santa Isabel, because they had sailed from Peru on that saint’s feast day, and went on to visit the neighbouring islands, which they called Guadalcanal, Malaita and San Cristóbal. Though a chief had greeted the Spanish visitors warmly on their first arrival, the natives could not satisfy their pressing demands for food; Mendaña had difficulty controlling his men – and blood, mostly native, soon flowed.

In August a disappointed Mendaña set sail from San Cristóbal. Having barely survived a hurricane, Mendaña and his officers had no idea where they were, how far they had travelled or when they might again reach land. Their few navigational tools would have included astrolabes and quadrants for determining latitude, magnetic compasses to steer by, hour-glasses for measuring short intervals of time, and lead-lines for sounding the depth in shallow water. But they had no proper charts and – crucially – no reliable means of judging how much progress they had made either to the east or to the west: only by estimating the ship’s speed through the water could the pilots assess how far they had travelled. This was a deeply unreliable method.

The agonizingly long return journey took Mendaña in a wide circuit across the North Pacific to reach the coast of Baja California in December 1568. He and his crew were reduced to a daily allowance of 6 ounces of rotten biscuit and half a pint of stinking water. Scurvy swelled their gums until they covered their teeth, they were racked by fever and many went blind. Every day they had to throw overboard another corpse. It was not until the following September that Mendaña finally reached Peru. He had found no riches, no continent, had made not a single convert and had failed to establish a colony, but his extraordinary voyage was to become a legend. Though he had been obliged to mortgage his property to get his ship repaired in Mexico, rumours spread that he had come home laden with gold and silver. The islands he had discovered were soon known by the name of the fabulously rich king of the Old Testament: Solomon.3 The longitude that he assigned to the Solomon Islands was so wildly inaccurate that subsequent explorers repeatedly failed to find them and eventually began to doubt their existence.4 It was to be 200 years before any European set foot on the Solomons again.

Mendaña himself failed to find the islands he had discovered when he mounted another, completely disastrous transpacific expedition in 1595, accompanied by Pedro Fernández de Quirós as chief pilot. He died in the Santa Cruz Islands – pathetically close to his goal – and Quirós eventually brought the disappointed survivors home to Peru via Manila after ‘incredible hardships and troubles’.5 Later generations of mariners and cartographers, deprived of detailed information about these voyages by the secretive Spanish authorities, struggled to make sense of Mendaña’s claims, and the Solomon Islands shifted giddily about the Pacific, varying in longitude by thousands of miles and even in latitude from 7 degrees to 19 degrees South. In 1768, within the space of a few months, two European mariners – Carteret and Bougainville – passed among the Solomons again, but without even realizing that they were following in Mendaña’s wake.6 They were soon followed by a French trader, Jean de Surville (died 1770), who visited the islands in 1769. Having closely investigated the accounts of these voyagers, and compared them to the descriptions that Mendaña had given, Jean-Nicolas Buache de Neuville (1741–1825)7 understood that the Solomon Islands had at last been rediscovered, though his arguments were not immediately accepted. His fellow countryman La Pérouse was to lose his life in trying to confirm his theory. Rear Admiral Joseph-Antoine Bruny d’Entrecasteaux finally settled the matter when searching for La Pérouse in the 1790s. He recognized many of the islands that Mendaña had described and decently restored to them the Spanish names that had been bestowed on them so long before.

The finding of the Solomon Islands, their subsequent ‘disappearance’ and eventual rediscovery perfectly illustrate the difficulties that confronted transoceanic navigators of the early modern age. It would be easy to multiply examples of this kind, which reveal the intimate, reciprocal dependence of navigation and hydrography – a recurrent theme of this book. The point is a simple one, but easily overlooked. To find the way safely, a mariner needs a chart that accurately records the positions of all that is navigationally significant – from the outlines of the major landmasses to the precise locations of tiny, uninhabited shoals on which a ship could founder. To make such charts, however, the hydrographer must first know the exact positions of everything that is to appear on them. Hydrography serves navigation, but only if nourished first by the fruits of navigation.

Two hundred and fifty years ago it was not just the location of the Solomon Islands that lay in doubt. Though it is hard for us to imagine such a state of affairs, the shapes of whole continents then remained largely unknown, and accurate charts – even of European waters – did not exist. The main reason for this state of ignorance was the imperfection of the art of celestial navigation and in particular the impossibility of determining longitude with any precision on board ship. In 1714 an Act of Parliament was passed in Great Britain designed to encourage the development of a practical shipboard solution to this age-old problem. It was not the first such prize but it turned out to be the last. Within fifty years, and in the space of a single decade, two radically different solutions emerged, one mechanical and the other astronomical (see Chapter 6). The long-running and often ill-informed tussle between the advocates of these two methods has obscured the fact that both depended on a newly developed observational instrument: the sextant.8 Though its praises have seldom been sung, the sextant was to play a crucial part in shaping the modern world – both literally and figuratively.

*

The sextant, like the anchor, is a familiar symbol of the maritime world, but to most people – including many sailors – its purpose is a mystery. One strand of my task is to sketch the developments in astronomy, mathematics and instrument-making that first permitted navigators to fix their position with its help. But I also wish to bring the sextant to life by examining some of the astonishing feats of the explorers who put this ingenious instrument to such good use in making the first accurate charts of the world’s oceans. The work of the pioneering marine surveyors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries – some of whom are almost forgotten – is another key strand. Because it is such a wide subject I have focused on those who worked in the Pacific, which was then the subject of greatest interest; the examples I have chosen illustrate some of their most remarkable achievementsfn1 as well as the many challenges they faced.9 I have also squeezed in the stories of three exceptional small-boat voyages, each of which depended crucially on skilful celestial navigation: Captain Bligh’s journey from Tonga to Indonesia after the Bounty mutiny, Joshua Slocum’s circumnavigation of the world in his yacht Spray, and Sir Ernest Shackleton’s remarkable rescue mission crossing the Southern Ocean in the James Caird, piloted by Frank Worsley.

To speak of the ‘discovery’ by European navigators of lands that had long been inhabited by other peoples is obviously absurd, if not insulting, but since the focus of this book is a European invention Europeans unavoidably take centre stage. By way of contrast, I have mentioned briefly the extraordinary skills of the Polynesian navigators, who found their way across the wide expanses of the Pacific using neither instruments nor charts long before the arrival of western explorers. Their achievements deserve to be better known, but they have been well described by others,10 and this is not the place in which to discuss them more fully.

This is not a ‘how to’ guide to celestial navigation, but I hope I have given enough information to enable the reader to grasp its basic principles. I have also tried to give some sense of what it feels like to navigate across an ocean in the old-fashioned way, with sextant and chronometer. Many of the great explorers who wrote about their experiences did so for fellow professionals who needed no explanations, while those who addressed the general public must often have supposed that descriptions of celestial navigation would make dull reading. Anecdotes from Slocum and Worsley have helped me to fill this gap, but I have also drawn on my own – far more modest – experiences, including those recorded in a journal I kept when sailing across the Atlantic as a teenager forty years ago.

For 200 years mastery of the sextant was a vital qualification for every ocean-going navigator. Hundreds of thousands of young men (women seldom had the opportunity) worked hard to learn the theory and practice of celestial navigation, and experts wrote manuals that sold in large numbers to cater for their needs. But the use of the sextant is now an endangered skill that is most commonly learned only to provide a safety net should the now ubiquitous Global Positioning System (GPS) fail.11 Very few practise taking sights at sea as a matter of routine, and most sailors now rely almost entirely on electronic navigation aids. The sextant, if not yet forgotten, has been relegated to a very occasional understudy role. Almost without notice the golden age of celestial navigation has drawn to a close.

If this book has an elegiac tone, it is not merely an exercise in nostalgia. I hope and believe that the sextant has a useful future – that it is not destined to join the many outmoded scientific instruments preserved only in museums. It would, of course, be more than a little eccentric to dismiss the convenience (and reassurance) of electronic guidance systems, but reading off numbers from a digital display is a very thin, prosaic experience compared with the practice of celestial navigation. GPS banishes the need to pay attention to our surroundings, and distances us from the natural world; although it tells us precisely where we are, we learn nothing else from it. Indeed unthinking reliance on GPS weakens our capacity to find our way using our senses. By contrast, the practice of celestial navigation extends our skills and deepens our relationship with the universe around us.

What could be more wonderful than to join the long line of those who have found their way across the seas by the light of the sun, moon and stars? Just as interest in classic boats, built in traditional ways and shaped only by the demands of beauty and seaworthiness, has undergone a revival, so the joys of navigating with a sextant are now ripe for rediscovery.

Chapter 1

Setting Sail

Sextant: I was nine years old when I first heard that magical word. It was 1963 and I had gone with my family to see Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Trevor Howard as the notorious Captain Bligh, whom he played as a choleric middle-aged martinet, and Marlon Brando as his infuriatingly condescending, toffee-nosed first officer, Fletcher Christian.fn1 A luscious, big-budget movie, shot in the South Pacific around Tahiti, it ends with the burning of the Bounty by some of the mutineers after their arrival at the remote (and then incorrectly charted) Pitcairn Island. Fletcher, the leader of the mutiny, tries in vain to save the ship and, before abandoning it, calls out over the roar of the flames to his friend:

Fletcher: ‘Have you got the sextant, Ned?’

Ned [unable to hear]: ‘What?’

Fletcher [shouting desperately]: ‘Have you got the sextant?’

Ned: ‘No!’

[Fletcher dashes for the companionway that leads to the Captain’s cabin below the burning decks]

Ned [yelling in alarm]: ‘You can’t go now – it’s too late, Fletcher!’

Fletcher [rushing below regardless]: ‘We’ll never leave here without it!’

Fletcher dives into the blazing cabin and is horribly burned trying – in vain – to recover the precious instrument, later dying on the shore as the ship goes down in a shower of steam and sparks.

*

My father loved astronomy and, as a civil engineer, he had been trained in surveying and map-making. It was he who first showed me the night sky when I was a very small boy, standing in our Hampshire garden on many cold, clear winter nights beneath the dark Scots pines. He taught me to recognize the flattened ‘W’ of Cassiopeia, the great torso of Orion, and Ursa Major (the ‘Big Dipper’) with its twin pointers – Dubhe and Merak – that lead the eye to the North Star: Polaris. The Milky Way, I learned, was a galaxy composed of billions of stars to which our sun and solar system belonged as just one very small element.

As we left the cinema I asked my father what a sextant was, and why it mattered so much. I do not remember exactly what he said, but I gathered that it was a device for fixing your position anywhere in the world, on land or sea, by reference to the sun and stars – and that it was a vital tool for navigators sailing out of sight of land. Coupled with the terrifying image of Fletcher Christian diving into the inferno, his words caught my imagination: the thought of being marooned for ever on a small, remote island, unable ever to find the way home, was haunting. How could so much depend on one small instrument? And how could the unimaginably distant sun and stars help a sailor find his way across a vast ocean?

This was the beginning of my fascination with the art of navigation. I lived in a town on the south coast of England where sailing was a part of everyday life, and I first went out in an old-fashioned clinker-built dinghy with my parents when I was not much more than a toddler. I still remember dozing off on a sail-bag, tucked up under the half-deck, listening to the slap of the water on the bows, hypnotized by the gentle, broken rhythm of the waves. Later I sailed a dinghy of my own and crewed racing yachts, but I never much liked competitive sailing. What I loved was pilotage – the business of reading a chart, plotting a course, making allowances for compass variation and the effects of tidal streams, and all the other tricks of the coastal navigator’s trade.

Charts fascinated me. Those published by the British Admiralty were then still printed from engraved plates, and their appearance had not changed much since the nineteenth century. They had a solemn gravity, reflecting as they did the accumulated data of generations of dedicated marine surveyors. The traditional saying – ‘Trust in God and the Admiralty chart’ – was a measure of their exalted reputation. Unlike their metric successors, the old charts were soberly black and white. Prominent features on dry land that might be useful to the navigator – like church steeples or mountains – were shown, and detailed views of the coast were often included in the margins to aid recognition of important landmarks or hazards: the old surveyors were all trained as draughtsmen. Wrecks were marked with a variety of warning symbols depending on how much water covered them; those that broke the surface even at high water were marked with a grim little ship, slipping stern-first beneath the waves. The nature of the ‘ground’ (that is, the seabed) was indicated in a simple code – ‘m’ for mud, ‘sh’ for shingle, ‘s’ for sand, ‘rk’ for rock, ‘co’ for coral and so on. Charts vary enormously in scope: the large-scale ones of harbours might cover an area of only a few square miles, while others cover entire oceans. The smaller-scale ones are framed by a scale of degrees and minutes of latitude (north–south) and longitude (east–west), and the surface is carved up by lines marking the principal parallels and meridians – an abstract system of coordinates first conceived by Eratosthenes (c.276–194 BCE) and then refined by Hipparchus (c.190–120 BCE). Compass ‘roses’ help the navigator to lay off courses from one point to another, and show the local magnetic variation – the difference between true north and magnetic north.

From my father I learned something about surveying and the use of trigonometry – the mathematical technique for deducing the size of the unknown angles and sides of a triangle from measurements of those that are known. On our walks in the New Forest we sometimes came across the concrete triangulation pillars on which the British Ordnance Survey maps were based. Each pillar formed the corner of a triangle from which the other two corners were visible. Starting from a very accurately measured baseline, a network of such triangles extended across the whole country. By measuring the angles between the pillars using a theodolite, surveyors could determine the relative positions of each pillar with great accuracy, thereby providing the map-makers with an array of fixed points on which to build. In those days this system was still the key to land-based cartography.

Every marine chart was liberally sprinkled with ‘soundings’ – numbers representing the depth of water in old-fashioned fathoms (1 fathom to 6 feet), which crowded in even greater profusion round hazardous patches of sea. Particularly sinister were the places in the mid-ocean depths where a tight cluster indicated an isolated shoal – perhaps the tip of a ‘sea mount’ that did not quite break the surface. The Chaucer Bank, some 250 miles north of the Azores in the middle of the North Atlantic, is an example. On Admiralty chart no. 4009 (North Atlantic Ocean – Northern Portion, published in 1970) it rose up to a ‘reported’ minimum depth of 13 fathoms from waters that slide down rapidly to 1,000 fathoms or more. In heavy weather, seas would break on such a shoal – an alarming sight so far from land, and a potential hazard too. Before the advent of the electronic echo sounder in the 1920s all these soundings would have been taken with lead-lines – nothing more than a lump of lead on the end of a long, calibrated rope or wire. Triangulation could have been used the fix the positions of soundings along the coast, but what about those offshore, far out of sight of land? Of the vital part the sextant had played in hydrography – the mapping of the seas – I had as yet no idea.