Полная версия

Pretty Iconic: A Personal Look at the Beauty Products that Changed the World

Head & Shoulders is still the world’s bestselling shampoo, still has a strong, slightly chalky whiff of big box washing powder, and to give credit where it’s most due, it still works – with a couple of caveats. Head & Shoulders uses zinc pyrithione to control the levels of micro-organisms on the scalp (the most common form of dandruff comes from yeast growing in skin sebum) and so can only do its job for as long as you’re using it. If you stop, or dramatically cut down, your dandruff will return. And back to my school cardigan: I soon found that Head & Shoulders had little or no effect on me, because I didn’t have traditional dandruff from oiliness and sebum. I just had a dry scalp. If you’re the same, seek out a shampoo – preferably sulphate-free – for this specific problem and treat your scalp to the odd olive oil massage the night before shampooing. You’ll see much lighter snowfall.

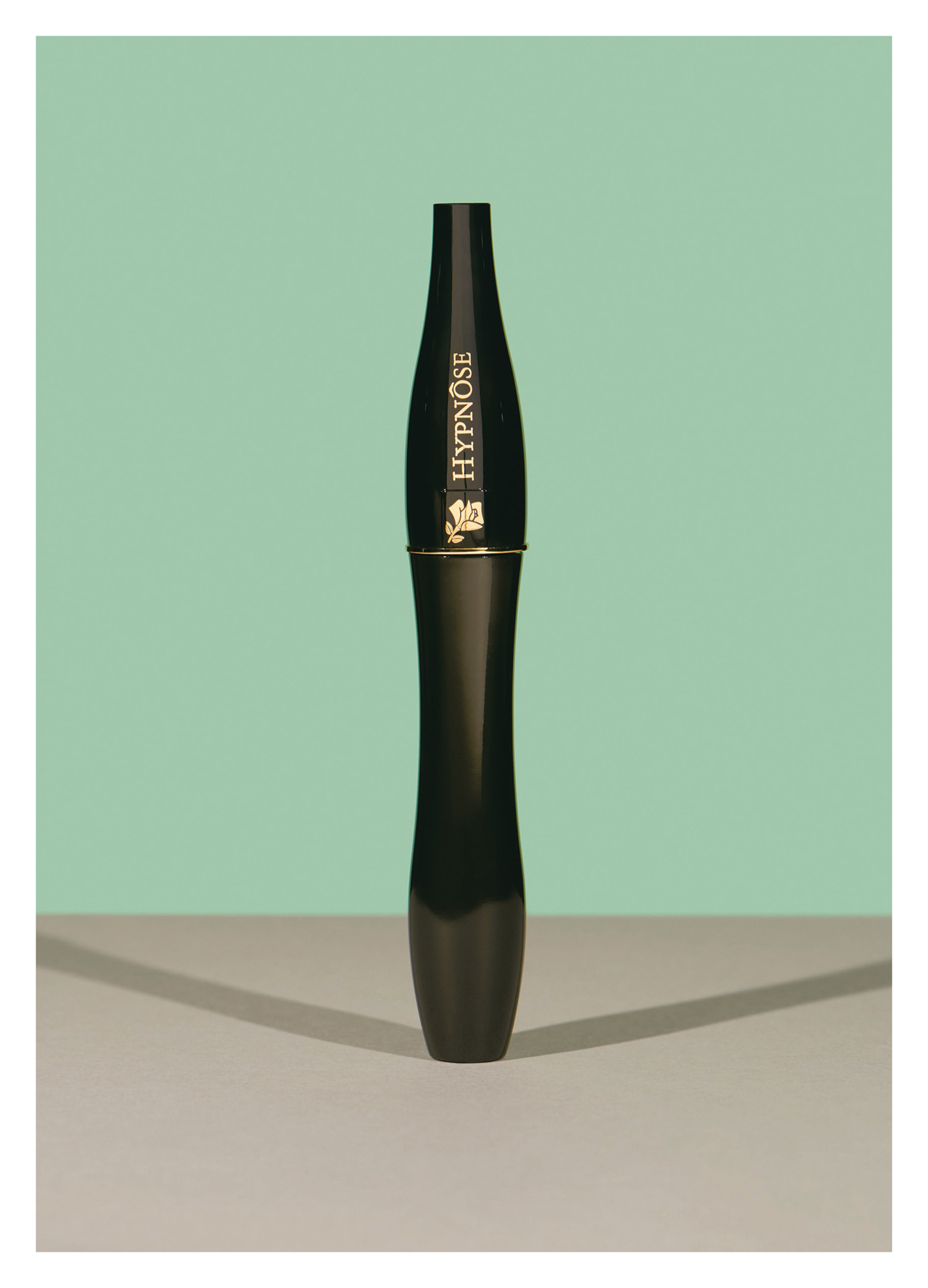

Lancôme Hypnôse Mascara

I’m sure I’ve mentioned it previously, but I hate most mascaras. Which is an inconvenience if you’d sooner saw off your big toe than never wear it again. My issue with it is that it’s not good enough. I so often despair of how little progress the industry has made over the years in developing just one mascara that does everything I want: separate, curl, define, darken, thicken, lengthen, lift, stay, remove. On shoots, make-up artists will invariably use several different mascaras on just one model. Maybe a Maybelline to build up, a little Tom Ford to kick out at the sides, some MAC Gigablack to really blacken, some Kevyn Aucoin tubing to lock the whole thing down … Now brands are pushing this whole (potentially very lucrative) mascara portfolio nonsense, but really, who on earth has the time? I’m lucky to get two coats on between Brighton and Hayward’s Heath, never mind rustle around for different wands for different jobs.

But what I’ve found, time and time again, when looking into the make-up bags of industry figures as pushed for time and space as the rest of us, is this. When it comes to mascara, most experts will agree that Lancôme is a safe pair of hands. They know their mascara better than almost anyone and for a number of years were head and shoulders above the competition. They make no attempt at subtlety (natural-looking mascaras are the chocolate teapot of beauty), but go all out for the kind of fluttery, separated and thickened lashes most of us desire. The formula of Hypnôse is neither wet and messy, nor dry and spiky. It stays fresh for longer, the expertly designed brush coats each and every lash perfectly. The black is real black, not some insipid shade the colour of a faded sock. It is probably the best we have.

Vaseline Petroleum Jelly

In terms of iconography, Vaseline is the Campbell’s soup tin, Coke can or Brillo pad box of beauty. Practically everyone owns it, and those who don’t could readily identify its blue-capped jar – and probably list at least five uses for its contents, some of them downright filthy. Robert Augustus Chesebrough, a 22-year-old British chemist, could not have conceived of such success when he invented Vaseline by chance in 1859. He was visiting a Pennsylvania town where petroleum had recently been discovered. He became intrigued by the by-product of the oil-drilling process and observed the oil workers rubbing drill residue into their cuts and burns to heal them. Inspired, he triple-distilled it, cleaning out impurities (Vaseline is still the only petroleum jelly that goes through this process), perfecting the formula over ten years. He then opened a factory in New York and got on his horse and cart to sell his ‘Wonder Jelly’ to the public (mainly by burning himself with acid before an audience, then smearing the wound with it, like some sort of lunatic).

It was a massive success. He renamed it, expanded his distribution, and soon found himself at the helm of a large beauty brand, growing by the month. His petroleum jelly was taken by explorers on the first successful expedition to the North Pole (on account of it not freezing), was made standard issue for US soldiers in the trenches of the First World War, coated special healing gauze for use on the front line during the Second World War, and was stocked in both hospitals and home first-aid kits. A tub of Vaseline is sold every thirty-nine seconds somewhere in the world, and is utilised in a vast petroleum-based product range. Poured into a tin it becomes Vaseline Lip Therapy, the world’s biggest lip brand. Whipped with glycerin into lotion, it becomes Vaseline Intensive Care Lotion, the first port of call for many dry skin sufferers. In beauty alone, it has endless applications. It slicks down unruly brows, adds sheen to cheekbones, mixes with any powder to become coloured gloss, adds shine to legs, removes old glue from false lashes, blends with sugar to act as a lip scrub, diverts self-tan headed for dry spots, and lines cuticles to prevent nail polish migration. It is never missing from photo shoots, where in the past it even greased up camera lenses to give film stars a misty, otherworldly glow.

I myself am not the biggest fan of paraffins and mineral oil in expensive products (although my skin doesn’t particularly object to them). I believe that brands expecting you to spend big bucks on skincare should first dig deep into their own pockets and use much nicer plant oils that won’t cause breakouts. But in products as cheap as Vaseline, I’m more charitable, if not a particularly committed user myself. There’s an honesty here. What you see is what you get – a cheap, greasy petroleum jelly that fulfils its promise to temporarily moisturise, lubricate and seal. It is deeply unpretentious, egalitarian, often appropriate and much loved by millions. In my view, there are now far better products for each one of its uses. But none that do all of them at once, and certainly none as truly iconic.

Maybelline Great Lash

In the early 1900s T.L. Williams made, from dyes and Vaseline, a mascara for his little sister Maybel, and called it Lash-Brow-Ine. The solid, cake formula was to name and launch the Maybelline brand, but its enduring status as the high street/drugstore mascara specialist came via Great Lash in 1971. If I was asked to close my eyes and think of a mascara, I’d see the gaudy hot pink and lurid green of Great Lash. Its iconic status is in part down to this packaging (virtually unchanged since launch), so far along the trashy and kitsch continuum that it emerges completely fabulous at the other end. But there’s more about Great Lash than an instantly recognisable tube. It is the one mascara one unfailingly sees on photo shoots, television make-up room tables or film sets.

There are several reasons for this: it’s proper, opaque, dark soot-black, not that semi-transparent dirty puddle shade so woefully common in cheaper mascaras. Also, the brush (any good mascara is a 50/50 combination of formula and brush shape) can be manoeuvred into the deepest set eyes, along even the puniest lashes to give excellent definition. Its finish is slightly wet-looking, its formula is thin enough to be layered ad infinitum like mattresses atop the princess’s pea, until lashes are thick and spiky, like sixties Twiggy’s. It doesn’t go crunchy, dry or flake onto cheeks.

It isn’t the mascara I unfailingly turn to by any means (it doesn’t quickly give the dramatic, kittenish lashes so many of us crave, and it smudges on me – but then so do 95 per cent of all mascaras), but undeniably it represents a starting point for most of what came after. The original cake may be long gone, but Great Lash, along with Full ’n’ Soft (a more natural-looking mascara, woefully unavailable in the UK – do try it if ever Stateside), remain, as do various Great Lash spin-offs, including a waterproof formula. I’m glad original Great Lash remains relatively untouched, as it should.

Kiehl’s Creme De Corps

I could have chosen any one of a handful of iconic products from cool New York apothecary brand Kiehl’s. Creme With Silk Groom, the hairstyling cream so loved by session hairdressers to give sleek, ungreasy definition to shorter styles and crazy curls, perhaps (not that I have ever in my life got to grips with it). Or Blue Astringent Herbal Lotion, a potent toner that makes you momentarily brace. Certainly Kiehl’s lip balm qualifies easily, since so many beauty fans, myself included, made pilgrimages to London’s Liberty or Harvey Nichols to pick up a tube before Kiehl’s was on every high street. But from all of Kiehl’s products, I’ve concluded that the true icon is Creme de Corps, the celebrated cocoa butter and sesame oil body cream, loved for its richness and superior moisturising on very dry skin.

This thick, custardy cream, smelling weirdly, but pleasingly, like the paint in a primary school craft lesson, was among the first products developed by Irving Morse, the Russian-Jewish immigrant who bought the original East Village Kiehl’s apothecary-style store in 1921. It has remained a Kiehl’s bestseller ever since. It’s a fairly uncompromising product that relies on word of mouth among dry and sensitive skin sufferers. Even on the thirstiest skins, rubbing it in can be like kneading dough, and if you’re sitting on a nice white towel at the time, you can expect it to be stained temporarily with crème brûlée smears and blotches (it’s only the beta carotene and nothing more sinister). But the results are fabulous: skin is sort of cocooned in rich moisture, not greasy and grubby-feeling. It’s very good at giving shins an even, very slightly shiny finish, and at improving the look of blotchy upper arms. It’s great for post-tattoo healing and on babies and children with eczema and other dry skin conditions (oh, that I’d had Creme de Corps as a kid). It’s the loveliest product to slather thickly on post-bath skin, then get into clean pyjamas and a freshly made bed, phone on divert, massive mug of tea and a remote control at one’s side.

There’s a whipped version in a tub, though I’ve had much less success with it. It has a more matte finish but starts to bobble and peel away if you massage too hard. There’s a lighter version too, though I feel it rather misses the point of Creme de Corps, which is to baste skin in rich, fatty moisture (oily or normal skins might as well get something cheap). But the original bottled Creme is still absolutely wonderful on my dry skin. Regular use certainly improves skin condition over time, but it’s what I use occasionally when I’m going somewhere special, when I want my bodycare to hold up to a posh perfume, blow dry, make-up and frock. Because Creme de Corps is an expensive treat, albeit one that goes an awfully long way. Don’t make the mistake of thinking you can get round the problem by buying cheaply from eBay. Kiehl’s simple packaging (unless one of the very lovely limited edition Creme de Corps designs) is way too easy for counterfeiters to mimic and you end up with something similar to UHT milk tinted with yellow food colouring. I bear the mental scars.

Eucerin Aquaphor

Having spent my childhood coated in thick, unctuous petroleum-based lotions in a host of generic white bottles, itching like mad and being teased mercilessly by classmates, I really should hate Eucerin. It’s an unsexy, slightly joyless brand that makes skincare feel like a chore not the pleasure it can be. And yet weirdly, it has slipped past my firewall against mineral oil-rich pharmacy-shelf brands, and somehow occupied a place close to my heart. There are some excellent products in the range, some of which I’ve been recommending for many years. The Hyaluron Filler serum and creams, for example, are brilliant on dry and dehydrated skin, plumping up lines and restoring some perk.

But Eucerin’s icon comes in the form of Aquaphor, an ointment used widely since 1925 in medicine and in homes, nicknamed ‘The Duct Tape of dermatology’ by the very many doctors who swear by it. For them, Aquaphor’s appeal lies in its ‘semi-occlusive’ formula, meaning that while it traps in moisture and provides a barrier against germs, it still allows oxygen and moisture to reach the skin to aid wound healing. For beauty lovers, Aquaphor offers uncommon versatility. It works as an excellent humectant on dry lips, wind-chapped limbs and cuticles, as a tamer of brows and a subtle gloss for mouth and cheeks, a curer of nappy rash, and as a handy barrier against hair dye staining (just apply it around the hairline before mixing the colourant, then leave it until you’ve done your final rinse). It contains mineral oil, and so I wouldn’t recommend it as a face cream – although plenty happily use it as one without breakouts or irritation – but regardless of skin type, it’s well worth keeping a tube in your bathroom for all else.

Burt’s Bees Beeswax Lip Balm

It’s true to say that it’s much harder for a small company to create an icon than it is for some huge multinational whose research, development, marketing, advertising and PR spend is, metaphorically speaking, a bottomless cup of coffee. It’s perhaps harder still to do it while refusing to compromise on your principles of self-sustainability and all-natural formulas, and yet the thoroughly good eggs at Burt’s Bees somehow pulled it off. It started in Maine, when local artist and single mum Roxanne Quimby was trying to thumb a ride home. Burt Shavitz, a local beekeeper who sold honey from the back of his truck, stopped. The pair got chatting and Burt offered to give Roxanne any unused wax from his hives, so she could make it into candles. The candles, fashioned into fruits and vegetables, were beautiful, and their success allowed the pair to fund their next project, a beeswax lip balm.

To say this sweet, simple, natural, homespun product took off would be to grossly understate the achievements of Burt’s Bees. The cruelty-free lip balm, devoid of traditional ingredients of petroleum jelly, mineral oil or camphor, packaged in either its classic round bee print tin or a convenient stick, is a product that sums up perfectly the cult beauty movement of the 1990s, where customers sought out quirky, one-off products by cool brands outside the megabrand triumvirate of L’Oréal – Estée Lauder – LVMH. Burt’s Bees’ message of authenticity, nature and simplicity was, and still is, extremely appealing. I can think of no other product that infiltrated the snobbish cult beauty market via the shelves of health food stores, or as a novelty item sold in gift shops, and yet by virtue of being both effective and rather lovely, this succeeded. Burt’s Bees’ pluck, size and product range are already enough for me, before even factoring in what a thoroughly decent company it is. There are now many good products in the Burt’s Bees range (the Almond and Milk Hand Cream, which smells intoxicatingly like newborn babies wrapped in marzipan blankets, is my favourite), but the first and bestselling lip balm formula remains its queen bee.

Estée Lauder Advanced Night Repair

There are several reasons Advanced Night Repair deserves both your respect and its iconic status. Launched in 1982, it was the world’s first consumer skincare serum. The idea behind it was that unlike moisturising creams, which have to pack in emollients, sun protection and thickening agents to deliver the right protective texture, a serum could have a much finer texture, smaller molecules and be stuffed predominantly with ingredients that fixed specific skin concerns. While a cream sat on the top of the skin, an inherently finer serum could dig a little deeper. In creating Night Repair (the ‘Advanced’ came later, and since then, it’s been known in the business as simply ‘ANR’), Estée Lauder completely changed the conversation around skincare. We were no longer talking merely about lovely creams that made us feel nice, but questioning the old wives’ belief that mere moisture kept skin looking its best. ANR was about specific problem-solving with active ingredients, and when it came to choosing those ingredients, the Lauder team struck gold.

Hyaluronic acid is a viscous fluid substance found naturally in the human body, particularly around the eyes and connective tissue, where its primary function is to keep things moist, mobile and comfortable. Its magic is in its ability to hold a thousand times its weight in water. Scientists began to wonder if its topical use could help dehydrated, crêpey, ageing skin do the same, plumping it up a little, like a raisin dropped in warm water. The research team at Lauder felt it could, and combined the hyaluronic acid with antioxidants and other actives to build the world’s first skin serum. The effect hyaluronic acid has had on beauty products across every price point and category cannot be overstated – it’s in practically everything you’d ever want to put on your face. It’s the one ingredient whose absence I will almost immediately notice. Estée Lauder Advanced Night Repair was so unique and so revolutionary that even now, when the market is rammed with serums for every conceivable purpose, it still has over twenty-five worldwide patents and patents pending, and remains one of the world’s bestselling serums.

Whether or not you like ANR (and ironically, as I get older, I find its hyaluronic punch lands a bit too softly for me personally and the recent revamp – distinguished by a ‘II’ after its name – was fine, but something of a missed opportunity), its impact on skincare globally has been absolutely enormous. The little apothecary bottle and pipette dropper we now just accept as standard serum packaging? ANR did it first. The concept of repairing past damage with skincare? Lauder invented it with ANR. A skincare revolution in one little brown bottle, ANR is a true beauty icon without whom your bathroom shelf might now look very different indeed.

Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser

This is a perfect example of how subjective skincare can be. For a good ten years, all any dermatologist seemed to recommend was Cetaphil, a relatively inexpensive and unfussy rinse-off cleanser available widely in the States but not, at that time, in the UK. While moisturiser, mask and serum recommendations were varied, Cetaphil seemed to be the doctors’ default cleanser of choice for almost any skincare gripe. If you had rosacea – try Cetaphil; if you were sensitive – stick to Cetaphil; if you’d just had a facelift – wash only in Cetaphil; if you were acne prone – well, you get it, I’m sure. The endless and uncritical love for Cetaphil was especially enticing to me because I have a serious obsession with American drugstores, and a disproportionate love for tracking down hard-to-find products. Truly, I’ve barely dumped my suitcase and passport in my hotel room when I’m on the sidewalk, charging towards the nearest Duane Reade or Walgreens to spend 200 unnecessary dollars on wholly unsuitable products because the font on the gaudy bottle looks pleasingly foreign. And so my love for Cetaphil seemed like a done deal.

Sadly, it failed the due diligence. While the friends for whom I brought back a bottle raved about Cetaphil, I was left wondering what all the fuss was about. First, it contains sulphates. I’m not a fan of these foaming agents in skincare, though I quite understand those who need the psychological boost of a foam. The problem is that Cetaphil is so low-foaming that one gets the worst of both worlds: my skin feels drier, only without that sense of squeaky cleanliness. Second, and for me crucially, Cetaphil is no good at all at removing make-up. The most thorough-seeming cleanse will still result in orange smears on the towel, making Cetaphil advisable only as a second night-time step. This flaw sums up my long-held belief that while dermatologists – whom I have utterly revered and valued since early childhood – are the final word on the science of skincare, their insight is often poor when it comes to real life outside a lab or surgery.

What I mean by that is while a great derm can tell you exactly which sunblock will best protect the skin without clogging pores, they will rarely know if it also peels off in lumps the minute you apply your foundation, rendering unusable even the best product in the world. Doctors are rightly thinking about skin health and efficacy, not lifestyle and quality of use. They correctly obsess over ingredients, while not always acknowledging that overall texture, packaging and formula can be the difference between addictive and useless. And so I concluded that Cetaphil was, for me, one such case in point. Almost everything about this legendary product looks good on paper, and I can understand why it’s so respected by doctors, even loved by so many consumers. It just doesn’t work for my life.

Dove Beauty Bar

I realised the other day when completing my online grocery shop that I buy more products by Dove than any other brand. To be fully transparent, I am extraordinarily lucky in that I don’t generally pay for many products at all – everything is sent to me before launching in the hope I like it and write something favourable. What I do buy is deodorant, razor blades, handwash, bar soap, toothpaste, shower cream and body lotion, mainly because when it comes to these items specifically I’m quite uncharacteristically brand loyal and have little appetite to experiment unless a work assignment demands it. Dove caters for many of my household toiletry needs: the shower cream (especially the Silk Glow version) stands permanently in the bathroom, cap flipped and ready for action. The original deodorant is the only one, I think, that doesn’t spoil the smell of a good shower with obtrusive scent. Desert Island Discs while soaking in Dove’s almondy bath foam is one of life’s true and guiltless pleasures. The liquid handwash, deliciously creamy and cheap, is the one I decant into the prettier bottles of luxury brands long since drained by my extravagant and undiscerning children.

Ironically, the one incarnation of Dove that I don’t like (men’s range aside, with its pointlessly gender-specific take on the already lovely unisex Dove scent) is the very foundation of every one of its products, and the only one truly deserving of the term ‘icon’. The Beauty Bar, launched in 1957, is a face soap and therefore no amount of added moisturiser – famously one quarter here – can persuade me to use it anywhere above the shoulders.

Neutrogena Norwegian Formula Hand Cream

The irony with Neutrogena is that I tend to back the wrong horse. One of my favourite products of all time is its Body Emulsion, an absolute godsend for serious dry skin sufferers that they’ve twice tried to discontinue (at time of writing, it is available again as Deep Moisture, but I live in a mild state of fear). I almost unfailingly adore Neutrogena suncare, and yet they choose not to sell it in Europe. The wonderful, moisturising Original Rainbath shower gel has been withdrawn from general circulation and must now be obtained like some grubby porno from online importers, and as for their peerless mid-price, retinol-based, anti-ageing skincare – will they ever see fit to share the love with Britain? Meanwhile, the appeal of Neutrogena’s internationally celebrated icons, namely T/Gel dandruff shampoo and Norwegian Formula Hand Cream, eludes me.