Полная версия

Pretty Iconic: A Personal Look at the Beauty Products that Changed the World

Of course, any Mason Pearson owner would be lying if they claimed not to have been drawn, at least in part, to its heirloom-worthy looks. The signature gold-blocked ‘Dark Ruby’ (black on first glance, a gemstone red when held up to the light) handle and orange rubber cushion make it utilitarian but elegant, and recognisable the world over. And despite the incomparability of the Mason Pearson, so many are still trying to copy it, even marking up the already painful price point. It’s wholly unseemly and I reject them utterly.

Clairol Herbal Essences

Let’s be perfectly honest, there’s nothing exceptional or special about Herbal Essences shampoo and conditioner. They smell rather lovely, they do the job perfectly well, they come at a great price point, can be bought anywhere and their name sounds pleasingly like a reggae compilation album circa 1973. What makes them iconic is a single marketing campaign, conceived as a do-or-die last-chance saloon for a tired-looking haircare franchise at Clairol, at a time when Herbal Essences was a generic family haircare brand with no USP to speak of. By the late 1990s, beauty brands using natural plant extracts were a dime to a dozen, many of them doing it more thoroughly and more authentically. Herbal Essences had always been marketed at everyone, and thereby appealed to no one.

Ad execs decided to give the brand a boot up the backside with a campaign zoning in on women rather than the entire family. Borrowing heavily from Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally, the groundbreaking new campaign featured women, standing alone in the shower, loudly climaxing as they lathered up with Herbal Essences shampoo, suggesting that this run-of-the-mill brand was far from an unremarkable, stuffy seventies relic, but a ‘totally orgasmic’ experience. The ads were pretty tame – cheeky rather than softly pornographic – but for a generation of women who’d grown up in token sex education classes without ever hearing mention of the female orgasm, they represented a sea-change in middle-of-the-road beauty advertising and marketing. Herbal Essences was no longer about the dutiful housewife leaning over the bath to wash her children’s hair while a chicken roasted in the oven, it was a brand for women and recognised their need for ‘me time’ (I promise I will never use this mortifying expression again). Of course, the campaign rather overstated the product’s effects – unless a woman was to be more imaginative with the water hose, a shower with Herbal Essences was unlikely to yield greater results than cleaner hair. And it’s true that after we became inured to the original gimmick, and other brands pushed the envelope further, Clairol was back to square one. We now lived in a world where reality TV stars had sex on telly and defecated in front of six hidden cameras.

In the mid-noughties, P&G, having acquired Clairol, redesigned and relaunched Herbal Essences, scrapping the pastel bottles and Totally Orgasmic Experience in favour of lurid brights and a red carpet-wannabe message. These effects were also short-lived. A few years later, P&G rightly went back to the old, by now iconic bottles and smells. Where that leaves Herbal Essences is anyone’s guess. Where it perhaps leaves women is with little more than sexual frustration and a pleasant, vaguely chemical herbal scent.

Old Spice

Old Spice Original, launched in 1938, is the smell from the backseat of my grandad’s brown Austin Allegro as he drove me to Little Chef for the giddy treat of jumbo cod, chips, banana split and a free lollipop for clearing my plate. Its warm, not-too-strong but lasting spiciness is the smell of day trips to Tenby, of candy-stripe brushed flannel sheets from the market, of a tiny metalwork room made from a cubby-hole under the stairs. It’s the smell of the armchair where we took Sunday naps during the rugby, had cuddles and belly laughs in front of Victoria Wood’s As Seen On TV, where my grandad sat patiently as I stood on a stool behind him, tying bows, plaits, jewels and fancy clips in his white hair, not giving a damn if he had to answer the door for the postman.

Old Spice is the scent of him trying to teach me long division when everyone else had long ago lost patience, of very gentle flirting with the checkout ladies at Kwiksave, of seemingly endless chats with every Indian and Pakistani immigrant in Blackwood to practise his beloved Urdu and Burmese learned during the Second World War in Burma. It’s the smell that filled a silent room whenever I asked what had happened to his friends there. Old Spice is the smell of his old shirt worn over my ra-ra dress to wash the car, of well-thumbed Robert Ludlum novels, of huge cotton handkerchiefs, of an often empty wallet, of the green zip-up anorak bought via twenty weekly payments from the Peter Craig catalogue. Old Spice was there when J.R. Ewing was shot, when I first saw Madonna on Top of the Pops, when the miners went back to work and when we sat under blankets at military tattoos, both of us weeping like newborns. Its absence was felt acutely when I last saw his face, eyes closed in the room of a hospice; when I got married and when my babies were born.

Clearly, I’m too sentimental about Old Spice for my opinion to be truly objective, but unlike so many other scents of my youth, I believe Old Spice Original (not its newer, nastier incarnations) is still a gorgeous fragrance in its own right. It’s neither ironic nor retro, just a wholly pleasant blend of nutmeg, cinnamon, clove, star anise, exotic jasmine, warm vanilla and sweet geranium, packaged in one of the most beautiful perfume bottles of all time. For the world’s bestselling mass-market fragrance, and an indisputable beauty and grooming icon, Old Spice Original still feels like a very unique and personal affair. I revere it for many reasons, but not least because, as its early ad campaign asserted, ‘You probably wouldn’t be here if your grandfather hadn’t worn Old Spice’.

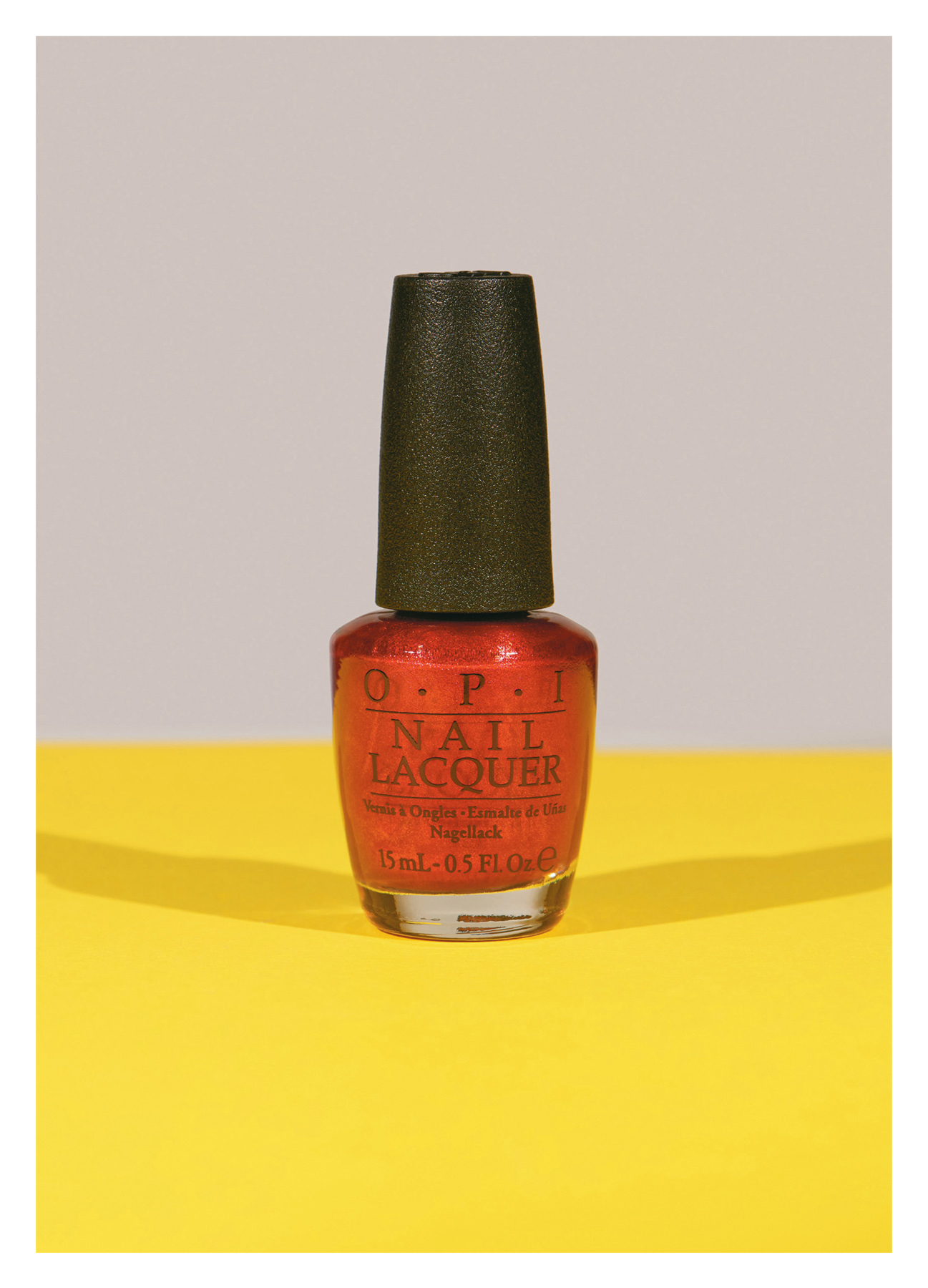

OPI I’m Not Really A Waitress

I give huge credit to OPI for creating a polish that in many ways has become as standard a red as that of London buses, award season carpets, Welsh Guards, the stripes on American flags and the coats on Chelsea Pensioners. It is consistently at number one across OPI’s shades and, cumulatively, is officially the brand’s bestselling lacquer of all time. For a polish launched as late as 1999, I’m Not Really a Waitress has certainly got around. Apart from being the go-to red for TV and film make-up artists who love its dense, multi-dimensional finish (it shows up really well on camera without stealing the scene), I’m Not Really a Waitress has featured as the $16,000 question on the US version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, been used as the colour reference point for a red Dell laptop and has won the Reader’s Choice Favourite Nail Colour Award in Allure magazine a staggering nine years on the skip. The seal on its iconic status: the Urban Dictionary even recognises I’m Not Really a Waitress as ‘The specific color of red nail polish that is used in countless movies and commercials for its sheer mass appeal’.

I agree that the key to its success is that I’m Not Really a Waitress truly looks good on everyone, and with everything. It’s a ruby slippers red that flatters black, brown, yellow, pink and white skins equally, and layers very well for greater depth. It looks expensive and neat, leaving nails like the bonnet of a metallic red Porsche. The sparkling – but not glittery – finish makes it glamorous enough for parties (it’s my default Christmas polish – so festive and jolly) but restrained enough for work meetings. The unforgettable if slightly annoying name also helps. Launched originally for OPI’s Hollywood Collection, the name – typical of the brand’s quirky wordplay – is a homage to wannabe movie stars making rent by waiting tables while they wait for their big break. And so it’s fitting, really, that I’m Not Really a Waitress has ended up making so many uncredited appearances in big Hollywood blockbusters.

Pantene Shampoo

I’m sent every conceivable hair product, including luxury shampoos costing upwards of £30, but there are times when nothing hits the spot like a two quid bottle of Pantene. There’s something about its mass-market chemical fragrance that has been weirdly sexy to me from the first time I encountered it in the 1980s, then allowing me to overlook its pretty revolting, albeit hugely successful, advertising slogan of ‘Don’t hate me because I’m beautiful’. Everyone used Pantene in those days (I once found myself in a famous supermodel’s bathroom and, not entirely without effort, discovered several Pantene bottles on the go). Personally, it was never my favourite shampoo and isn’t now. But it’s certainly more than serviceable, especially over periods of four to five weeks’ use (after that, it can be prone to causing build-up and lankness and will need to be swapped for a bit – unless you’re using the new-ish silicone-free version, where the problem is largely eradicated).

There’s more to Pantene than shampoo and conditioner, though, of course. The entire brand is based on the discovery in the 1940s by scientists at Swiss drug company Hoffmann-La Roche, that panthenol, a pro-vitamin of B5, had ‘healing effects’ on damaged hair. The Pantene brand – much posher in those days – was born and today (under the different ownership of P&G) there are dozens of hair conditioning products under its umbrella: decent masks, hairsprays and mousses for every hair type, and the world’s first 2-in-1 shampoo and conditioner (it was not, contrary to assumptions, Vidal Sassoon’s Wash & Go), all of them built around the same key ingredient of panthenol. Perhaps more relevant to my interests is the continuity throughout the line of that same unmistakable fragrance. It has the sweet, addictive, unisex scent I now think of as the generic smell of ‘clean hair’. I can’t imagine there’ll ever be a time I no longer crave it.

SK-II Facial Treatment Essence

When the SK-II brand arrived in Britain in the late 1990s, packaged in minimalist glass bottles and tubes, with little to no enclosed information, at an almost unprecedented price point, I’m afraid I largely ignored it on the basis that it seemed impenetrable and to fancy itself a bit too much. A few years later, make-up legend Mary Greenwell told me that her regular client Cate Blanchett absolutely swore by it and so, given that Blanchett has skin like vellum, it seemed mad not to at least give it a whirl. Despite my former misgivings, I loved it and was newly intrigued by its philosophy. I won’t tell it as wistfully nor as reverently as intended, but here goes: a little over thirty years ago, scientists observed that elderly workers in Japanese sake breweries had wrinkled faces but astonishingly soft, youthful, line-free hands. They analysed the fermentation liquid with which the workers were in constant physical contact, and after countless tests, they found the answer in a unique yeast strain they named Pitera. The ingredient, rich in over fifty minerals, organic acids, vitamins and amino acids, would form the basis of every product in SK-II, a new luxury anti-ageing skincare brand.

But in hindsight, the even bigger story was in the Japanese skincare rituals SK-II demanded. This was not your traditional Western cleanse, tone, moisturise-type deal. The two-step SK-II cleansing ritual alone took longer. What followed it was the cornerstone of the entire SK-II philosophy: Facial Treatment Essence. This is a treatment liquid (not a toner) containing over 90 per cent pure Pitera, applied directly to clean skin with either fingertips or a cotton disc. It was the first of its kind, and undoubtedly inspired the huge number of Japanese-style treatment essences we see in the West today. The act of double cleansing (not that I think it particularly necessary myself) is now the gold standard for many skincare fans, and the multi-step morning and night ritual is regarded by many as a perfectly normal and pleasurable way to spend the best part of an hour. For better or worse, SK-II certainly helped nudge us eastwards.

Bic Razor

It’s a bit odd, when you think about it, for a company’s two best known products to be a razor – and a pen. But such unlikely portfolio-mates make a lot more sense when you consider their common defining feature: cheap chuckability. Bic’s pens arrived first – a fabulous moment in company history coming after the war when Mr Bic (actually Marcel Bich) pleasingly bought the patent for the ballpoint pen from Mr Biro. Bich improved the design of the pen while dramatically lowering the price through mass production, and Bic’s brand value was born.

So when the company launched the iconic white and orange plastic disposable razor in 1975, it wasn’t the continuation of a heritage brand, the product of time-served artisans who’d been hand-crafting steel blades since the court of Louis XIV. It was a shrewd move by a company who knew how to make cheap stuff out of plastic and had spotted a way to make shaving one step less fiddly. Up to that point, cartridges had evolved to become both safer and more easily exchanged, but Bic’s disposable razor was the first that invited the user to bin the entire device. A minimalist design classic, the featureless T of the Bic razor offers no comfortable grip, no reassuring weight, no decoration.

But long superseded as it may be by multiple blades, multi-directional tilting heads and gel strips (and my legs certainly prefer them to a common Bic), there’s still an undoubted appeal to a razor you can buy in big bags like potatoes, grab one as needed, use once and throw away with minimal guilt. The more expensive and many-featured the modern blade, the greater the obligation to rinse and reuse, to tease out stubborn shavings from between the blades, to ignore the faded aloe strip and convince yourself there’re still two good shaves in it. Bic’s one-shave stand was revolutionary, its convenience for sleepovers, holidays and pre-payday frugality, deathless. The disposable razor is rightly considered not only a beauty icon, but one of the greatest single inventions of all time.

Nivea Creme

It seems that the more expensive and luxurious the skincare product I recommend (and I do so sparingly and with a sense of responsibility) in my journalism, the more likely it is for some wearyingly furious person to crash into my Twitter feed and tell me that her granny died at 109, with not a single wrinkle on her face, all thanks to carbolic soap and a daily spread of good old-fashioned Nivea Creme. This pure white multi-purpose moisturiser (named Nivea after the Latin word for snow), essentially unchanged for over a hundred years, has become the sort of figurehead for unfussy, no-nonsense beauty, devoid of vanity or frippery, the kind of unpretentious preparation that makes fools of the competition and its users. This, as well as being absurd – there’s nothing wrong with spending your own money on whatever you like – also rather sells Nivea short, because it was quite the cutting-edge skincare in its day and as a brand has continued to innovate ever since.

Nivea (part of the Beiersdorf company from day one) was the first mass-produced stable oil- and-water-based cream and remained the company’s sole product for many years, but from the Second World War onwards the brand rolled out many great products like body lotion, shaving cream, oil, shampoo and, later, the excellent male grooming, anti-ageing and suncare ranges we see today (I go nowhere in summer without Nivea’s ingenious handbag-sized tube of SPF30). But far from feeling irked by the anti-beauty brigade’s weapon of choice, I am cheered by the original Nivea Creme’s continued existence. It’s a lovely, sturdy little product for ungreasily moisturising and softening dry hands, arms, legs and feet. If you suffer no adverse effects from paraffin derivatives, there’s nothing to stop you wearing it on your face (the velvety finish makes for a surprisingly decent make-up base, as it happens). And despite Nivea Creme’s reputation for simplicity, it has perhaps the most beautiful fragrance on all the high street. It smells clean, slightly beeswaxy and super feminine – very similar, in fact, to Nina Ricci’s L’Air du Temps, only for less than the price of a Sunday newspaper.

Johnson’s No More Tears

My love of this product is merely notional, since I don’t recall ever having it in the house as a child, despite two babies arriving after me. Johnson’s baby shampoo – the first shampoo to utilise amphoretic cleansing agents, so gentle that they lightly cleaned without stinging the eyes – seemed like something owned by the kind of family who probably had a purpose-decorated nursery, a wallpaper border to match the Moses basket, a savings account opened and a school place lined up for a newborn. It wasn’t for big chaotic families like ours, prone to bathing babies in the kitchen sink, complete with Fairy Liquid bubble beard and reachable access to the bread knife.

It was decades later that I finally used No More Tears to wash my make-up brushes, the popular opinion being that it didn’t strip and dry out the bristles. I’m no longer convinced that it’s the best substance for such a job (I use any non-moisturising shampoo that happens to be in the shower), since No More Tears’ very mild cleansing action is aimed at babies who are barely dirty to begin with, never mind caked in old foundation and powder, but it’s true that if your brushes are used rarely or lightly, or your hair is pretty clean, then No More Tears will spruce up hairs nicely. The bright yellow formula, as you might expect, rinses quickly and smells deliciously of babies – sweet, comforting and cosy – and the pebble-shaped bottle is pleasingly unmodernised.

I bought some in readiness for my first baby, when just owning the right supplies made me feel in control, and whenever I used it I momentarily felt like a proper mum despite the fact that I was entirely at sea. And maybe that is exactly why Johnson’s No More Tears baby shampoo has been an unwavering, deeply loved icon since 1936. When the disorientating, confusing, guilt-ridden and anxious, albeit ultimately wonderful, experience of motherhood strikes, it stands nobly by the side of the bath, as reassuringly experienced as a nanny, making one feel as though everything will be okay.

Crème De La Mer

If I had a penny for every time someone sidled up to me at a function, found out what I do, and asked me, ‘Is Crème de la Mer really worth all that money?’, then I’d have enough cash to swim in the stuff. The expectation is that I’ll say either that this super-expensive moisturiser is miraculous and life-changing, or that it’s rubbish and dishonest (and you’ll find plenty of reviews online of people taking one of these two extreme positions). The reality, for me at least, is a tad more nuanced. Crème de la Mer was invented over fifty years ago by aerospace physicist Dr Max Huber, after he’d suffered burns in a laboratory accident and wanted to improve his scarred, damaged skin. He became obsessed with the way natural sea kelp retained moisture and regenerated itself and hand-harvested and fermented supplies for his experiments. He turned the fermented kelp into what he nicknamed ‘Miracle Broth’, combined it with simple skincare ingredients for minimal irritation, and Crème de la Mer was born. It’s a romantic story, but in beauty those are ten a penny.

What people really want to know is if it works. For me, I have to say in all honesty that it broadly does. My super-dry skin looks better when I use it. People invariably tell me I look well by the time I’m a third of the way into a jar. On the rare occasions I’ve experienced an allergic reaction to something else I’ve been testing, an instant switchover to Crème de la Mer (with Clarins SOS serum underneath) has metaphorically put out the fire in days. Friends who’ve undergone chemo tell me with utter conviction that it’s all their skin could tolerate at the height of related dryness and sensitivity (though I am certain some people would react to the inclusion of eucalyptus oil). I’m sure many would argue convincingly that this is psychosomatic, but I personally don’t think that matters in the least (if, God forbid, I’m ever seriously ill, I’ll want things that make me feel nice as much as I’ll want things that make me feel better, and woe betide anyone who preachily shoves Vaseline under my nose and tells me to use that instead).

Personally, I use this simple, uncomplicated, pleasurable cream as a skin saver when things go pear-shaped, not as a daily moisturiser, and certainly not as an anti-ageing cream. I suggest people should manage their expectations on that score – this is not a wrinkle cream, or an exfoliant, or an antioxidant of any remarkable merit. It’s a softening, soothing, rich, buttery moisturiser that looks and feels luxurious. You can certainly do as well for much less money and those with oily or combination skin are unlikely to find the original Crème suits them (bafflingly, it contains mineral oil. Some of the other products in the range, like the oil, do not). But nonetheless Crème de la Mer is an icon. Its launch, cachet and subsequent success absolutely marked a sea change in skincare – perhaps an unwelcome one, since in terms of exclusivity and high price point, it’s now far from unique – and, I think, helped spark an increased public interest in skincare. ‘It-creams’ (a term invented by the media for Crème de la Mer, but applied at one time to any cream over £50 – oh, but were that still exceptional) now exist in the portfolio of almost every luxury brand, and yet truly there is still no product more coveted, more intriguing to the average consumer after all these years, than Crème. So there is my answer. Imagine how many polite party-goers wish they’d never asked.

Head & Shoulders

I knew about Head & Shoulders before I even knew what dandruff was. The weird vase-shaped bottle lived around our bath and on TV commercials featuring brooding male models slowly raking their side partings to reveal for the camera an infestation of props department snow. They’d then lather one side of their scalp with Head & Shoulders, the other with a generic shampoo, the miraculous results shown on split-screen TV. It wasn’t until secondary school, and I discovered the pitfalls of wearing the regulation black cardigan, that I realised why – a few Timotei fanciers aside – seemingly everyone used Head & Shoulders. And it’s a credit to P&G’s clever marketing that a potentially embarrassing problem like dandruff became so normalised that the shampoo was such an accepted mainstream beauty staple. Celebrities such as Jeff Daniels, Ulrika Jonsson, Sofia Vergara, Jenson Button and now premiership goalkeeper Joe Hart have all cheerfully cashed a cheque regardless of the inherent implication they have scalp fungus. And why not?