Полная версия

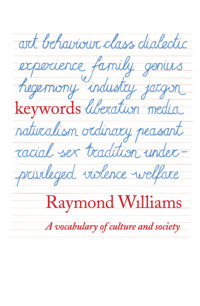

Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society

Keywords

A vocabulary of culture and society

Raymond Williams

Fourth Estate • London

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Preface to the Second Edition

Abbreviations

A

AESTHETIC

ALIENATION

ANARCHISM

ANTHROPOLOGY

ART

B

BEHAVIOUR

BOURGEOIS

BUREAUCRACY

C

CAPITALISM

CAREER

CHARITY

CITY

CIVILIZATION

CLASS

COLLECTIVE

COMMERCIALISM

COMMON

COMMUNICATION

COMMUNISM

COMMUNITY

CONSENSUS

CONSUMER

CONVENTIONAL

COUNTRY

CREATIVE

CRITICISM

CULTURE

D

DEMOCRACY

DETERMINE

DEVELOPMENT

DIALECT

DIALECTIC

DOCTRINAIRE

DRAMATIC

E

ECOLOGY

EDUCATED

ELITE

EMPIRICAL

EQUALITY

ETHNIC

EVOLUTION

EXISTENTIAL

EXPERIENCE

EXPERT

EXPLOITATION

F

FOLK

FAMILY

FICTION

FORMALIST

G

GENERATION

GENETIC

GENIUS

H

HEGEMONY

HISTORY

HUMANITY

I

IDEALISM

IDEOLOGY

IMAGE

IMPERIALISM

IMPROVE

INDIVIDUAL

INDUSTRY

INSTITUTION

INTELLECTUAL

INTEREST

ISMS

J

JARGON

L

LABOUR

LIBERAL

LIBERATION

LITERATURE

M

MAN

MANAGEMENT

MASSES

MATERIALISM

MECHANICAL

MEDIA

MEDIATION

MEDIEVAL

MODERN

MONOPOLY

MYTH

N

NATIONALIST

NATIVE

NATURALISM

NATURE

O

ORDINARY

ORGANIC

ORIGINALITY

P

PEASANT

PERSONALITY

PHILOSOPHY

POPULAR

POSITIVIST

PRAGMATIC

PRIVATE

PROGRESSIVE

PSYCHOLOGICAL

R

RACIAL

RADICAL

RATIONAL

REACTIONARY

REALISM

REFORM

REGIONAL

REPRESENTATIVE

REVOLUTION

ROMANTIC

S

SCIENCE

SENSIBILITY

SEX

SOCIALIST

SOCIETY

SOCIOLOGY

STANDARDS

STATUS

STRUCTURAL

SUBJECTIVE

T

TASTE

TECHNOLOGY

THEORY

TRADITION

U

UNCONSCIOUS

UNDERPRIVILEGED

UNEMPLOYMENT

UTILITARIAN

V

VIOLENCE

W

WEALTH

WELFARE

WESTERN

WORK

References and Select Bibliography

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

In 1945, after the ending of the wars with Germany and Japan, I was released from the Army to return to Cambridge. University term had already begun, and many relationships and groups had been formed. It was in any case strange to travel from an artillery regiment on the Kiel Canal to a Cambridge college. I had been away only four and a half years, but in the movements of war had lost touch with all my university friends. Then, after many strange days, I met a man I had worked with in the first year of the war, when the formations of the 1930s, though under pressure, were still active. He too had just come out of the Army. We talked eagerly, but not about the past. We were too much preoccupied with this new and strange world around us. Then we both said, in effect simultaneously: ‘the fact is, they just don’t speak the same language’.

It is a common phrase. It is often used between successive generations, and even between parents and children. I had used it myself, just six years earlier, when I had come to Cambridge from a working-class family in Wales. In many of the fields in which language is used it is of course not true. Within our common language, in a particular country, we can be conscious of social differences, or of differences of age, but in the main we use the same words for most everyday things and activities, though with obvious variations of rhythm and accent and tone. Some of the variable words, say lunch and supper and dinner, may be highlighted but the differences are not particularly important. When we come to say ‘we just don’t speak the same language’ we mean something more general: that we have different immediate values or different kinds of valuation, or that we are aware, often intangibly, of different formations and distributions of energy and interest. In such a case, each group is speaking its native language, but its uses are significantly different, and especially when strong feelings or important ideas are in question. No single group is ‘wrong’ by any linguistic criterion, though a temporarily dominant group may try to enforce its own uses as ‘correct’. What is really happening through these critical encounters, which may be very conscious or may be felt only as a certain strangeness and unease, is a process quite central in the development of a language when, in certain words, tones and rhythms, meanings are offered, felt for, tested, confirmed, asserted, qualified, changed. In some situations this is a very slow process indeed; it needs the passage of centuries to show itself actively, by results, at anything like its full weight. In other situations the process can be rapid, especially in certain key areas. In a large and active university, and in a period of change as important as a war, the process can seem unusually rapid and conscious.

Yet it had been, we both said, only four or five years. Could it really have changed that much? Searching for examples we found that some general attitudes in politics and religion had altered, and agreed that these were important changes. But I found myself preoccupied by a single word, culture, which it seemed I was hearing very much more often: not only, obviously, by comparison with the talk of an artillery regiment or of my own family, but by direct comparison within the university over just those few years. I had heard it previously in two senses: one at the fringes, in teashops and places like that, where it seemed the preferred word for a kind of social superiority, not in ideas or learning, and not only in money or position, but in a more intangible area, relating to behaviour; yet also, secondly, among my own friends, where it was an active word for writing poems and novels, making films and paintings, working in theatres. What I was now hearing were two different senses, which I could not really get clear: first, in the study of literature, a use of the word to indicate, powerfully but not explicitly, some central formation of values (and literature itself had the same kind of emphasis); secondly, in more general discussion, but with what seemed to me very different implications, a use which made it almost equivalent to society: a particular way of life – ‘American culture’, ‘Japanese culture’.

Today I can explain what I believe was happening. Two important traditions were finding in England their effective formations: in the study of literature a decisive dominance of an idea of criticism which, from Arnold through Leavis, had culture as one of its central terms; and in discussions of society the extension to general conversation of an anthropological sense which had been clear as a specialist term but which now, with increased American influence and with the parallel influence of such thinkers as Mannheim, was becoming naturalized. The two earlier senses had evidently weakened: the teashop sense, though still active, was more distant and was becoming comic; the sense of activity in the arts, though it held its national place, seemed more and more excluded both by the emphasis of criticism and by the larger and dissolving reference to a whole way of life. But I knew nothing of this at the time. It was just a difficult word, a word I could think of as an example of the change which we were trying, in various ways, to understand.

My year in Cambridge passed. I went off to a job in adult education. Within two years T. S. Eliot published his Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1948) – a book I grasped but could not accept – and all the elusive strangeness of those first weeks back in Cambridge returned with force. I began exploring the word in my adult classes. The words I linked it with, because of the problems its uses raised in my mind, were class and art, and then industry and democracy. I could feel these five words as a kind of structure. The relations between them became more complex the more I considered them. I began reading widely, to try to see more clearly what each was about. Then one day in the basement of the Public Library at Seaford, where we had gone to live, I looked up culture, almost casually, in one of the thirteen volumes of what we now usually call the OED: the Oxford New English Dictionary on Historical Principles. It was like a shock of recognition. The changes of sense I had been trying to understand had begun in English, it seemed, in the early nineteenth century. The connections I had sensed with class and art, with industry and democracy, took on, in the language, not only an intellectual but an historical shape. I see these changes today in much more complex ways. Culture itself has now a different though related history. But this was the moment at which an inquiry which had begun in trying to understand several urgent contemporary problems – problems quite literally of understanding my immediate world – achieved a particular shape in trying to understand a tradition. This was the work which, completed in 1956, became my book Culture and Society.

It was not easy then, and it is not much easier now, to describe this work in terms of a particular academic subject. The book has been classified under headings as various as cultural history, historical semantics, history of ideas, social criticism, literary history and sociology. This may at times be embarrassing or even difficult, but academic subjects are not eternal categories, and the fact is that, wishing to put certain general questions in certain specific ways, I found that the connections I was making, and the area of concern which I was attempting to describe, were in practice experienced and shared by many other people, to whom the particular study spoke. One central feature of this area of interest was its vocabulary, which is significantly not the specialized vocabulary of a specialized discipline, though it often overlaps with several of these, but a general vocabulary ranging from strong, difficult and persuasive words in everyday usage to words which, beginning in particular specialized contexts, have become quite common in descriptions of wider areas of thought and experience. This, significantly, is the vocabulary we share with others, often imperfectly, when we wish to discuss many of the central processes of our common life. Culture, the original difficult word, is an exact example. It has specialized meanings in particular fields of study, and it might seem an appropriate task simply to sort these out. But it was the significance of its general and variable usage that had first attracted my attention: not in separated disciplines but in general discussion. The very fact that it was important in two areas that are often thought of as separate – art and society – posed new questions and suggested new kinds of connection. As I went on I found that this seemed to be true of a significant range of words – from aesthetic to work – and I began collecting them and trying to understand them. The significance, it can be said, is in the selection. I realize how arbitrary some inclusions and exclusions may seem to others. But out of some two hundred words, which I chose because I saw or heard them being used in quite general discussion in what seemed to me interesting or difficult ways, I then selected sixty and wrote notes and short essays on them, intending them as an appendix to Culture and Society, which in its main text was dealing with a number of specific writers and thinkers. But when that book was finished my publisher told me it had to be shortened: one of the items that could be taken out was this appendix. I had little effective choice. I agreed, reluctantly. I put in a note promising this material as a separate paper. But the file of the appendix stayed on my shelf. For over twenty years I have been adding to it: collecting more examples, finding new points of analysis, including other words. I began to feel that this might make a book on its own. I went through the whole file again, rewrote all the notes and short essays, excluded some words and again added others. The present volume is the result.

I have emphasized this process of the development of Keywords because it seems to me to indicate its dimension and purpose. It is not a dictionary or glossary of a particular academic subject. It is not a series of footnotes to dictionary histories or definitions of a number of words. It is, rather, the record of an inquiry into a vocabulary: a shared body of words and meanings in our most general discussions, in English, of the practices and institutions which we group as culture and society. Every word which I have included has at some time, in the course of some argument, virtually forced itself on my attention because the problems of its meanings seemed to me inextricably bound up with the problems it was being used to discuss. I have often got up from writing a particular note and heard the same word again, with the same sense of significance and difficulty: often, of course, in discussions and arguments which were rushing by to some other destination. I began to see this experience as a problem of vocabulary, in two senses: the available and developing meanings of known words, which needed to be set down; and the explicit but as often implicit connections which people were making, in what seemed to me, again and again, particular formations of meaning – ways not only of discussing but at another level of seeing many of our central experiences. What I had then to do was not only to collect examples, and look up or revise particular records of use, but to analyse, as far as I could, some of the issues and problems that were there inside the vocabulary, whether in single words or in habitual groupings. I called these words keywords in two connected senses: they are significant, binding words in certain activities and their interpretation; they are significant, indicative words in certain forms of thought. Certain uses bound together certain ways of seeing culture and society, not least in these two most general words. Certain other uses seemed to me to open up issues and problems, in the same general area, of which we all needed to be very much more conscious. Notes on a list of words; analyses of certain formations: these were the elements of an active vocabulary – a way of recording, investigating and presenting problems of meaning in the area in which the meanings of culture and society have formed.

Of course the issues could not all be understood simply by analysis of the words. On the contrary, most of the social and intellectual issues, including both gradual developments and the most explicit controversies and conflicts, persisted within and beyond the linguistic analysis. Yet many of these issues, I found, could not really be thought through, and some of them, I believe, cannot even be focused on unless we are conscious of the words as elements of the problems. This point of view is now much more widely accepted. When I raised my first questions about the differing uses of culture I was given the impression, in kindly and not so kind ways, that these arose mainly from the fact of an incomplete education, and the fact that this was true (in real terms it is true of everyone) only clouded the real point at issue. The surpassing confidence of any particular use of a word, within a group or within a period, is very difficult to question. I recall an eighteenth-century letter:

What, in your opinion, is the meaning of the word sentimental, so much in vogue among the polite …? Everything clever and agreeable is comprehended in that word … I am frequently astonished to hear such a one is a sentimental man; we were a sentimental party; I have been taking a sentimental walk.

Well, that vogue passed. The meaning of sentimental changed and deteriorated. Nobody now asking the meaning of the word would be met by that familiar, slightly frozen, polite stare. When a particular history is completed, we can all be clear and relaxed about it. But literature, aesthetic, representative, empirical, unconscious, liberal: these and many other words which seem to me to raise problems will, in the right circles, seem mere transparencies, their correct use a matter only of education. Or class, democracy, equality, evolution, materialism: these we know we must argue about, but we can assign particular uses to sects, and call all sects but our own sectarian. Language depends, it can be said, on this kind of confidence, but in any major language, and especially in periods of change, a necessary confidence and concern for clarity can quickly become brittle, if the questions involved are not faced.

The questions are not only about meaning; in most cases, inevitably, they are about meanings. Some people, when they see a word, think the first thing to do is to define it. Dictionaries are produced and, with a show of authority no less confident because it is usually so limited in place and time, what is called a proper meaning is attached. I once began collecting, from correspondence in newspapers, and from other public arguments, variations on the phrases ‘I see from my Webster’ and ‘I find from my Oxford Dictionary’. Usually what was at issue was a difficult term in an argument. But the effective tone of these phrases, with their interesting overtone of possession (‘my Webster’), was to appropriate a meaning which fitted the argument and to exclude those meanings which were inconvenient to it but which some benighted person had been so foolish as to use. Of course if we want to be clear about banxring or baobab or barilla, or for that matter about barbel or basilica or batik, or, more obviously, about barber or barley or barn, this kind of definition is effective. But for words of a different kind, and especially for those which involve ideas and values, it is not only an impossible but an irrelevant procedure. The dictionaries most of us use, the defining dictionaries, will in these cases, and in proportion to their merit as dictionaries, list a range of meanings, all of them current, and it will be the range that matters. Then when we go beyond these to the historical dictionaries, and to essays in historical and contemporary semantics, we are quite beyond the range of the ‘proper meaning’. We find a history and complexity of meanings; conscious changes, or consciously different uses; innovation, obsolescence, specialization, extension, overlap, transfer; or changes which are masked by a nominal continuity so that words which seem to have been there for centuries, with continuous general meanings, have come in fact to express radically different or radically variable, yet sometimes hardly noticed, meanings and implications of meaning. Industry, family, nature may jump at us from such sources; class, rational, subjective may after years of reading remain doubtful. It is in all these cases, in a given area of interest which began in the way I have described, that the problems of meaning have preoccupied me and have led to the sharpest realization of the difficulties of any kind of definition.

The work which this book records has been done in an area where several disciplines converge but in general do not meet. It has been based on several areas of specialist knowledge but its purpose is to bring these, in the examples selected, into general availability. This needs no apology but it does need explanation of some of the complexities that are involved in any such attempt. These can be grouped under two broad headings: problems of information and problems of theory.

The problems of information are severe. Yet anyone working on the structures and developments of meaning in English words has the extraordinary advantage of the great Oxford Dictionary. This is not only a monument to the scholarship of its editors, Murray, Bradley and their successors, but also the record of an extraordinary collaborative enterprise, from the original work of the Philological Society to the hundreds of later correspondents. Few inquiries into particular words end with the great Dictionary’s account, but even fewer could start with any confidence if it were not there. I feel with William Empson, who in The Structure of Complex Words found many faults in the Dictionary, that ‘such work on individual words as I have been able to do has been almost entirely dependent on using the majestic object as it stands’. But what I have found in my own work about the OED, when this necessary acknowledgment has been made, can be summed up in three ways. I have been very aware of the period in which the Dictionary was made: in effect from the 1880s to the 1920s (the first example of the current series of Supplements shows addition rather than revision). This has two disadvantages: that in some important words the evidence for developed twentieth-century usage is not really available; and that in a number of cases, especially in certain sensitive social and political terms, the presuppositions of orthodox opinion in that period either show through or are not far below the surface. Anyone who reads Dr Johnson’s great Dictionary soon becomes aware of his active and partisan mind as well as his remarkable learning. I am aware in my own notes and essays that, though I try to show the range, many of my own positions and preferences come through. I believe that this is inevitable, and all I am saying is that the air of massive impersonality which the Oxford Dictionary communicates is not so impersonal, so purely scholarly, or so free of active social and political values as might be supposed from its occasional use. Indeed, to work closely in it is at times to get a fascinating insight into what can be called the ideology of its editors, and I think this has simply to be accepted and allowed for, without the kind of evasion which one popular notion of scholarship prepares the way for. Secondly, for all its deep interest in meanings, the Dictionary is primarily philological and etymological; one of the effects of this is that it is much better on range and variation than on connection and interaction. In many cases, working primarily on meanings and their contexts, I have found the historical evidence invaluable but have drawn different and at times even opposite conclusions from it. Thirdly, in certain areas I have been reminded very sharply of the change of perspective which has recently occurred in studies of language: for obvious reasons (if only from the basic orthodox training in dead languages) the written language used to be taken as the real source of authority, with the spoken language as in effect derived from it; whereas now it is much more clearly realized that the real situation is usually the other way round. The effects are complex. In a number of primarily intellectual terms the written language is much nearer the true source. If we want to trace psychology the written record is probably adequate, until the late nineteenth century. But if, on the other hand, we want to trace job, we have soon to recognize that the real developments of meaning, at each stage, must have occurred in everyday speech well before they entered the written record. This is a limitation which has to be recognized, not only in the Dictionary, but in any historical account. A certain foreshortening or bias in some areas is, in effect, inevitable. Period indications for origin and change have always to be read with this qualification and reservation. I can give one example from personal experience. Checking the latest Supplement for the generalizing contemporary use of communications, I found an example and a date which happened to be from one of my own articles. Now not only could written examples have been found from an earlier date, but I know that this sense was being used in conversation and discussion, and in American English, very much earlier. I do not make the point to carp. On the contrary, this fact about the Dictionary is a fact about any work of this kind, and needs especially to be remembered when reading my own accounts.