Полная версия

Jog on Journal: A Practical Guide to Getting Up and Running

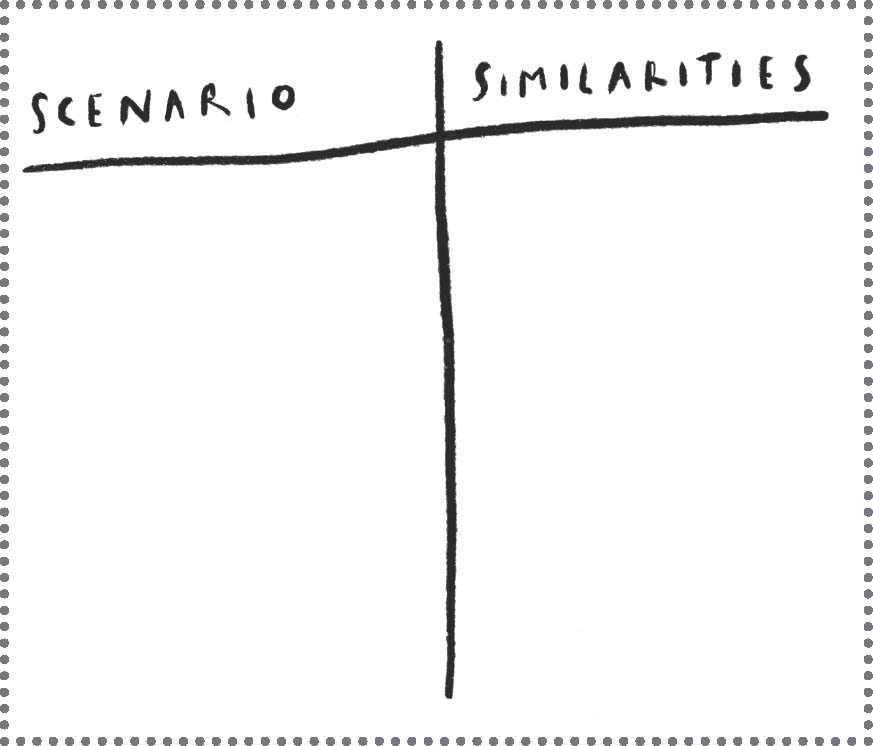

Can you write down examples of your anxiety and see what the similarities are? It’s good to spot the patterns your worries take, even if they seem completely different initially.

What can you take away from the comparison? Do both scenarios involve a specific place? Or a time when you’re tired? Begin to notice what common threads link your worries and remind yourself of them when you next feel anxious.

How can you stop catastrophising? We’ll talk about this a lot more as we go on, but here are a few tips:

• Notice what your brain is doing – it’s a lot easier to calm yourself down if you catch the pattern early.

• View the thoughts from a distance. It helps me to internally say: ‘Ah, I see I am spiralling into doom-laden thoughts. I wonder why I’m going there.’

• Evaluate why you’re going there – are you tired? Are you hungry? Do you have a presentation to give tomorrow? Are you pre-menstrual? Sometimes it helps to figure out a real-life fire-lighter that might be stoking the worry.

• Don’t berate yourself too much – it never helps to call yourself a dick. Instead, go easy – a sort of ‘Thanks for trying, but not today’ reply to your mind.

• That said, dispute the worry – don’t discount it completely, but question it. I use this with flying: ‘But planes are the safest way to travel, Bella.’ Might sound small, but it has an impact.

• Figure out what you CAN do to help ease the worry – practical things, like paying a bill or setting aside time to write that presentation. Start somewhere, even if it’s small.

• If all else fails, distract yourself with something comforting – I bake or listen to old Agatha Christie audiobooks when my mind is spiralling. Often doing something with your hands can help quieten your mind.

PART THREE

FIGHT-OR-FLIGHT

The term ‘fight-or-flight’ sounds really dramatic – as though you’re about to go to rumble à la West Side Story. If you’ve not seen the film, go and watch it. Tony. That’s all I’ll say about that.

It’s important for people with anxiety (and those with many other mental-health disorders, from PTSD to bipolar) to familiarise themselves with this very normal human reaction, because it comes from fear – and fear is the sensible and reasonable cousin of anxiety. The cousin who calls your grandma on her birthday. The cousin who trained for years and makes your mum wonder why you never became a doctor. And yes, I am stretching this metaphor, thank you for noticing.

Anyway. Fear is healthy – we need it. It’s how we know to get out of a burning building. And it does this with the fight-or-flight response. This physical reaction – when the human body produces a bunch of hormones to make you faster and stronger in the event of … oh, let’s say a lion attack – is a wonderful thing, but our brains respond identically to both real and unreal danger. So the fight-and-flight mode that equips us to fight terrifying animals can also kick in on a Monday morning rush-hour commute when there is no obvious threat. And for people prone to anxiety … well, this response can start working against us.

The fight-or-flight response does a bunch of stuff to your body when it kicks in – your amygdala (the part of the brain which processes emotions) sends out a sort of distress signal and your body knows to gear up for a scary situation. You produce more adrenaline, your heart rate goes up, you breathe faster and you get a rush of energy. It’s thought that this all happens before your conscious brain has even considered what’s happening (and explains why a person could jump in front of a train to save a person who’s fallen on the tracks).[2]

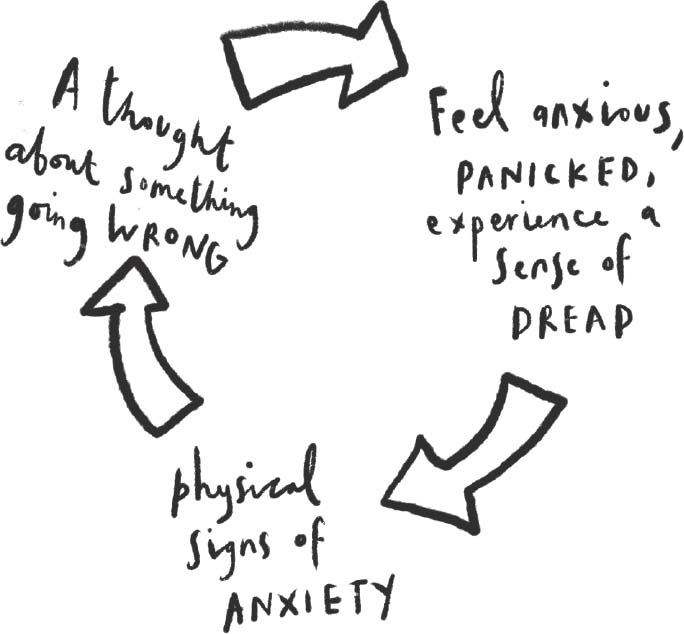

In a scary situation this is all GREAT! But if there’s no immediate emergency and yet your brain goes on sending the danger alert, then your body keeps producing the adrenaline and this keeps your brain thinking there’s something going wrong. That feeling of excess energy, that pounding heart. Think about how that feels. It’s not nice, huh? So of course if you’re feeling all of those things, your mind is still casting around for peril. And so the cycle begins.

Sound familiar?

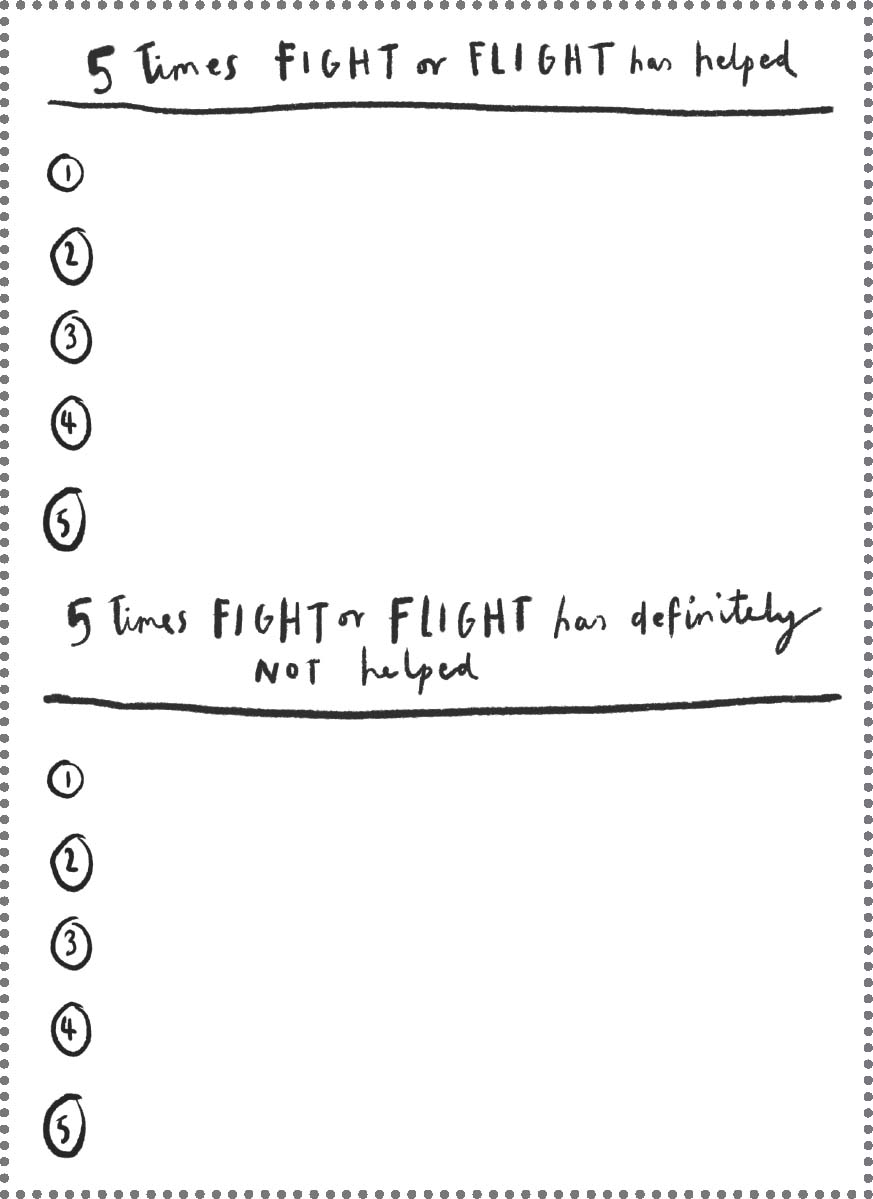

It might be helpful here to write down five times your fight-and-flight response has kicked into gear for a GOOD reason. And then write down five times it’s reared its head in an unhelpful way. We need to make an effort to distinguish the normal fear reaction from the excessive and unwarranted fear reaction so that our brains are better able to respond appropriately in a future stressful situation.

Just as with catastrophising, you can help push back against this. It’s exhausting to get trapped in such a cycle. You spend hours, days, weeks feeling full of adrenaline – teeth grinding, sweating, humming with nerves – and then you crash and can be overwhelmed with headaches, tired to your very bones, feel shaky and achy as though you have the flu. And, long term, cortisol (the stress hormone) isn’t very good for you – it’s been shown to prompt weight gain, affect blood pressure and mess with cholesterol.[3] And the rest. Anxiety really is the gift which keeps on giving.

Some things that help put the brakes on this cycle:

• EXERCISE (there may … just may be more about this later).

• MEDITATION AND MINDFULNESS.

• SOCIALISING – studies have shown that a ‘tend and befriend’ response can lower these symptoms of stress – providing safety and security instead of panic.[4]

• LAUGHTER – sounds simple, but has been shown to reduce stress hormones and promote mood-elevating hormones like endorphins.[5]

Above all, it helps to reassure yourself. It sounds silly, but sometimes just saying, ‘I am safe’, as many times as I need to (internally or out loud), can really help calm my body down in moments when I want to get the fuck out of a place that my body is telling me is scary. Try it, see how it feels after you’ve spoken positively to yourself. Our internal voices are so often complicit in making us feel worse – and it’s a ‘skill’ we build up over many years, so it’s understandably hard to break. But with practice, you can make that voice more sympathetic and less willing to just go along with the latest worry that might have popped into your brain. Reassuring yourself is a good way to start. It can be any mantra as long as it’s positive and calming – ‘I can do this’ is another good one.

Write down three things you might say to yourself next time you feel panic rising and keep them at the back of your mind for future use:

PART FOUR

PANIC ATTACKS

Since we’ve discussed catastrophic thinking and fight-or-flight, let’s look at panic attacks – often the end result of the fight-or-flight response. Have you had a panic attack? If you’re reading this book, it’s likely that you have. Some statistics say that 13 per cent of people have had one in their lifetime.[6] And some people will only have one or two – triggered by a stressful period in their life like a new job or a bereavement. Some people will have tons. At that point, you might have panic disorder. That’s an anxiety condition – under the umbrella of issues that anxiety covers. Panic attacks are debilitating. They can make you think you’re dying – so often people who experience them initially think there’s something seriously wrong physically. When I first experienced them, I thought I was having: a heart attack, a stroke, a brain aneurysm. Often you think you’re about to pass out. Let me get this straight first up: YOU ARE NOT GOING TO PASS OUT.

Probably. I’m not a doctor. But many doctors have told me that panic attacks rarely lead to fainting. You might feel dizzy for sure, and the earth might feel like it’s moving beneath you, BUT: during a panic attack, your heart beats faster, and your blood pressure rises. When people faint it’s normally because of a sudden drop in blood pressure.[7] So strike that off your list of worries. I’ve had so many panic attacks I could write a thesis on them, and I’ve never once fainted during an episode. From kissing a boy aged eighteen, sure, but never from a panic attack. Remind yourself of this – it’s important! So many people develop a fear that they’ll pass out and it can bring on the anxiety cycle we talked about earlier. If you feel wobbly, sit down for sure, drink some water, but don’t worry you’re going to stack it right outside Starbucks, because you won’t.

OK, good – moving on. I’m going to write down a list of panic attack symptoms – and you tick the ones you’ve experienced.[8] This isn’t an exhaustive list but these are the very common ones. It’ll be like a fun puzzle exercise, except it’s about mental illness and there’s no fun involved. Tricked you. OK, GO!

Truly horrible bloody things. What’s your worst symptom? Mine is that I can’t breathe. I pull at my throat and gasp a lot. Which makes me think that people must be noticing my freak-out and that can make me more panicky. But here’s the thing. Mostly, panic attacks are happening beneath the surface – like when a serene duck is barely moving on the water but actually its feet are frantically paddling. All the things going on in your mind and in your body feel IMMENSE but are normally not visible to a passer-by. Think about how many times you have seen a stranger having an anxiety attack – I’ve never seen one person experience one and I have them myself. So put that worry out of your head. So many people worry that they’ll cause a scene and look stupid when, in actual fact, human beings are really self-absorbed and barely notice anything you’re doing unless you fall over. Then they notice, trust me (I fall over a lot).

The irony of it all is that actually a really good thing to do when you’re feeling a panic attack coming on is to talk to someone. Make a human connection, look into someone else’s eyes and force your brain to concentrate on something else. And this isn’t only a practical bit of advice. In my quest to get everyone on earth (I’m grandiose like that) talking about mental health, I think it would be amazingly helpful if we could tell a stranger that we’re feeling a bit anxious without feeling silly or ‘mad’. If someone told me they were panicking I’d try and be as helpful and reassuring as possible – as would most people, I think. Wouldn’t it be lovely if we felt able to do that?

There’s lots of advice on how to overcome panic attacks – from your GP to charities like MIND, from eminent psychiatrists to quack practitioners. Some of it’s good, some of it’s unhelpful. I’m not a professional (at literally anything) so all I can tell you is what works for me. And normally it’s a multi-pronged approach – no ONE thing is guaranteed to nail it. What helps is having a toolbox full of things that help and being able to pull them out when needed.

• Focus on your breathing. In situations like this, there’s a right way and a wrong way to breathe. You probably take shallow breaths when you start to panic – and many people start to hyperventilate (inhaling deeper or taking quicker breaths than usually).[9] Normally, you breathe in oxygen and breathe out carbon dioxide (hello GCSE science). But when you hyperventilate, the carbon dioxide levels in your bloodstream drop. You start to feel sick or dizzy, and this provokes more panic. So you need to calm your breathing down. Easier said than done, I know. I begin by taking one big breath and telling myself, ‘I CAN breathe.’ Breathe in through your nose, and put one hand on your chest and one on your stomach. Notice the breath move through your body – you should feel your stomach move but your chest should remain pretty still. Keep doing this for as long as you need to until you’re convinced that you can breathe.

• Find a quiet place to sit down. If you feel like you’re going to faint (even though you’re not), take a seat, but don’t hunch up. Keep your chest broad so that you can keep on taking proper breaths.

• Notice your surroundings. It helps me to focus on the sky, or on an interesting building, or to watch a dog walk past. Anything to centre you back in your surroundings.

• Try not to rush away. The instinct is SO strong to get the fuck out and head for ‘safety’ but, in doing so, you can set up problems for yourself in the future. If you feel scared in a place and leave before you calm down and realise that there’s nothing to really fear, then your brain tends to designate that place as ‘unsafe’. Then you start to avoid places and your world can get really small really fast. So stick it out if you can. Just as an example, leaving the scene of a panic attack meant that I later avoided:

– Planes

– Lifts

– Busy spaces

– The centre of London

– Sainsbury’s

– Theatres and cinemas

– Motorways

– Coaches (not really, I just don’t like coaches. Not enough toilets)

• Focus on your senses. Touch something soft, stroke your own arm, smell the air. Panic attacks can make you feel very far away from your own body – try and reconnect with it.

• Talk to someone – make eye contact. Stroke a dog, smile at a waiter. It can help to make you see that you’re not in danger. If there’s nobody around, call a friend and tell them that you just need two minutes to talk – a little encouragement from my sister really helps when I’m feeling like I might have an attack.

• Expect that afterwards you’re likely to feel exhausted, trembly and sometimes a little teary. The adrenaline has dissipated and your body is wrung-out. Get yourself some food, drink lots of water, sit down for a bit. Keep warm – often panic attacks leave you cold and shivery. Be nice to yourself; don’t berate yourself, don’t tell yourself it’s pathetic. Nobody asks to have panic attacks – it’s not a sign that you’re weak or incapable. Tell yourself that you’re OK, you handled it well, you’ve done well to get through it. Anxious people have minds working against them, the last thing you need is to add fuel to that.

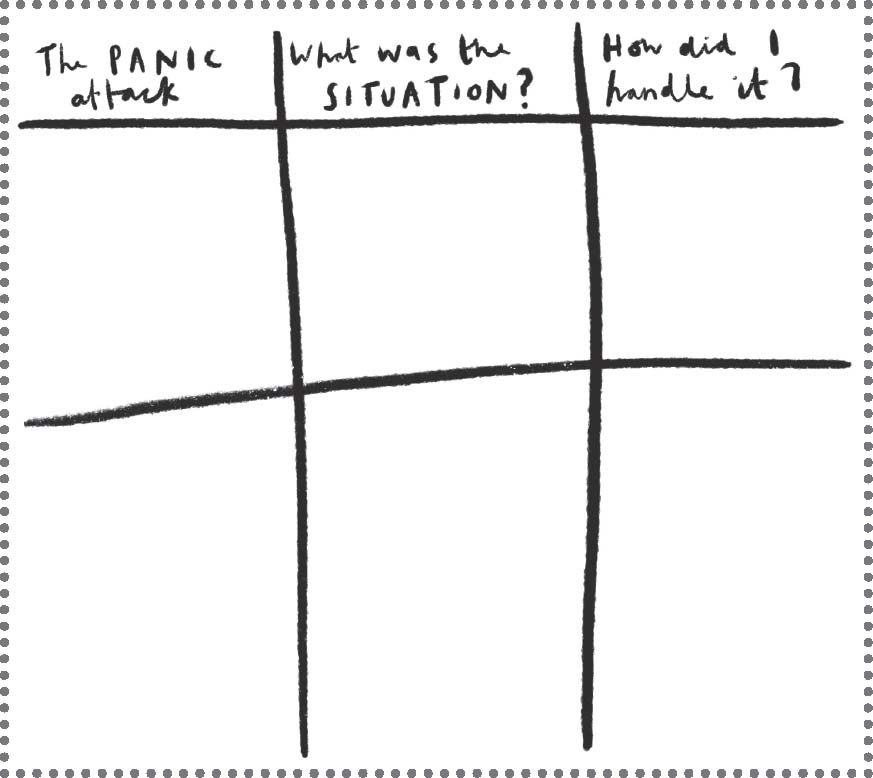

It’s important to know that while panic attacks are a beast, you will not die. They feel awful and, boy, do they take it out of you, but they cannot hurt you. Knowledge is power, and the more you understand why you’ve had an episode and the more you KNOW they’re not dangerous, the less hold they have on you. With that in mind, it might be good to write down a bit about two times you had an attack and the events surrounding them. It’s helpful to know your triggers and arm yourself with that information.

There are lots of ways to help prevent panic attacks – and again, you’ll find your own tools. But here are a few suggestions:

Avoid caffeine – anxious people have so much adrenaline, we don’t need any more encouragement.

Avoid nicotine and wine – but I guess you know this one anyway.

Try yoga/breathing exercises/meditation – which are all known to help with stress and calm people down.

Exercise – yup hi, we’ve got this one covered.

Get enough sleep – sleep disturbance is often high in people with mental-health problems and it contributes to anxiety FOR REAL.[10] However you do it, make it a bigger priority.

Eat regularly. When my blood sugar drops I can feel my anxiety climbing. I try and eat every hour, which is fun and also makes me feel like a baby. Try not to forget to eat and then grab a sugary doughnut. I mean, for sure have doughnuts, but just make sure you have proper meals too.

Do things that scare you – this sounds sinister but we’ll get to it and it won’t sound so odd, I promise.

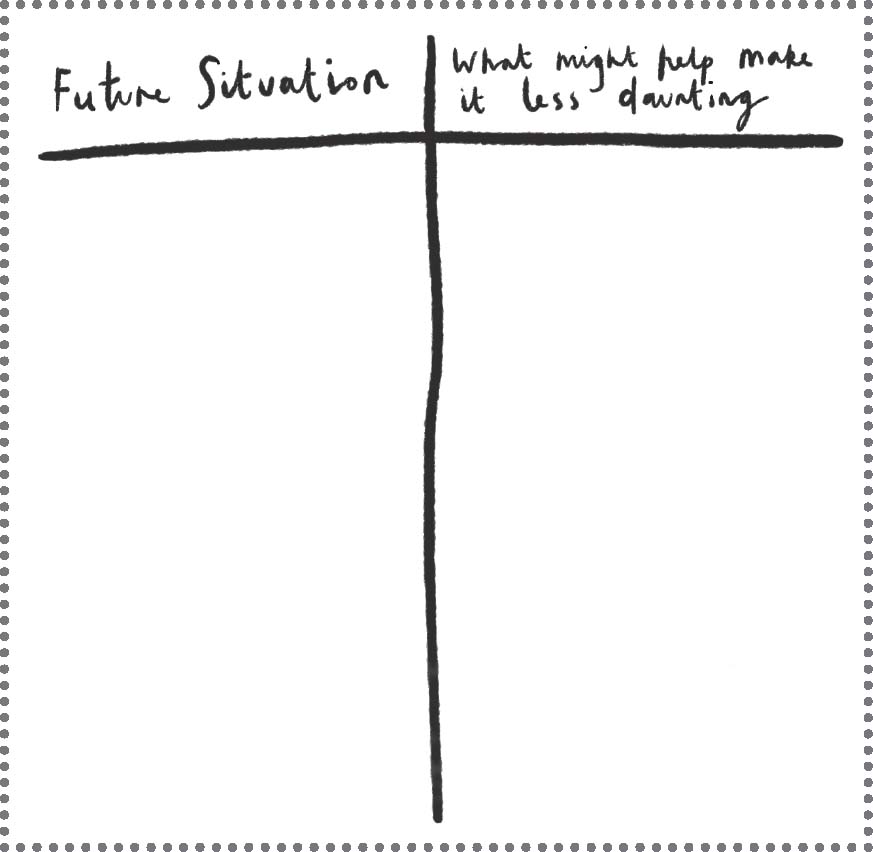

When a situation is looming that you find scary, plan for it. I research routes in advance so that I’ll be somewhat familiar with them. I sometimes look on Google Maps and see what a venue looks like – not to plan my exit but just so I feel comfortable when I get there. This is all a way of me having an element of control over my worries. I accept I can’t plan everything ahead, but I can show my anxious brain some research and say, ‘Hey look! This doesn’t look so bad, does it?’ So much of learning to tackle anxiety is reframing your thoughts and changing the narrative in your brain. Can you start here by writing about a situation coming up soon that is making you feel a bit nervous? What would help you to stop dreading it and, if not look forward to it, then at least not let it weigh too heavily on your mind?

PART FIVE

PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS

Our minds and bodies are closely linked. Yes, that sounds mega obvious, but honestly, how often do you really take time to think about what your body might be telling your brain when it aches and feels tired? Or connect your low mood to the fact that you’re getting over a bout of the flu? Yes, we all know that we’re one connected being, but I think mostly we tend to view our brains as one thing and our bodies as another. I suspect many of us put our brains on a pedestal – prizing intellect – while seeing our bodies as cart horses, pulling us along. And that’s not even touching on how many of us hate our bodies, see them as inferior, lacking. Too big, too short, too hairy …

The philosopher René Descartes proclaimed that the mind and body were two separate entities – with the mind a thinking but immaterial thing, and the body an unthinking but physical presence.[fn1] Prior to this, the mind and body were closely linked according to Christianity – and many illnesses were attributed to the victim’s conduct, explained away with the notion that the person must have ‘sinned’.[11] This meant that for the soul to ascend to heaven, the human body had to be intact. So theories like that of Descartes helped pave the way for medical innovation, but dismissed the bearing that the mind and body have on each other.

Nowadays, medical professionals increasingly approach treatment in a more integrated way.[12] GPs offer advice on exercise for a range of health problems and in some cases cancer patients are offered yoga and meditation to help cope with their treatment. Some surgeons even compile playlists for operating theatres, based on research that suggests that music can help reduce pain before, during and after a procedure.[13]

And yet Descartes’ philosophy still holds a grip on some of us. In extreme cases, people take pills for their mind, go to the gym to hone their body – or worse, sit inert – and never connect the dots. I didn’t, not for thirty years of my life. Many people with anxiety become huge hypochondriacs (ME!) and STILL don’t link up their aches and pains with their mental health. Online forums are full of scared people talking about twitchy feet and pins and needles and back ache and nausea and stomach upsets. But OF COURSE our bodies are influenced by our minds. The mind is a powerful thing. It can make you feel cripplingly ill without anything being actually wrong. Except that’s bunkum – because OF COURSE something is wrong there – something is very wrong, it’s just not in your body.

The book It’s All in Your Head by Suzanne O’Sullivan explores this in the most sensitive and empathetic way I’ve ever read.[14] O’Sullivan is a consultant neurologist, and treated many patients – some of whom were not actually physically ill.[15] She had patients who went blind, lost the use of their limbs, had seizures and who were convinced they had terrible illnesses that were going to be fatal. As O’Sullivan says, ‘In 2011, three GP practices in London identified 227 patients with the severest form of psychosomatic symptom disorder. These 227 constituted just 1 per cent of those practice populations – but estimates suggest up to 30 per cent of GP encounters every day are with patients who have a less severe form of the illness. If psychosomatic symptoms are so ubiquitous, why are we so ill equipped to deal with them?’