Полная версия

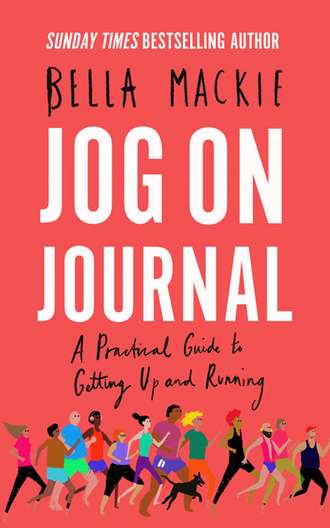

Jog on Journal: A Practical Guide to Getting Up and Running

JOG ON JOURNAL

A Practical Guide to Getting Up and Running

Bella Mackie

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Isabella Mackie 2019

Illustrations by Anna Morrison

Isabella Mackie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears here.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008370039

Ebook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008370046

Version: 2019-11-01

Dedication

For everyone who got in contact with me after Jog On came out and trusted me with their mental health stories – this journal is for you

A NOTE FOR EBOOK READERS:

You will need a blank notebook and a pen to get the most out of the Jog On Journal.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

A NOTE FOR EBOOK READERS

INTRODUCTION

SECTION ONE: MENTAL HEALTH

1 GETTING HELP

2 THE ANXIETY UMBRELLA

3 FIGHT-OR-FLIGHT

4 PANIC ATTACKS

5 PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS

6 INTRUSIVE THOUGHTS

7 BAD COPING SKILLS

8 GOOD COPING SKILLS

SECTION TWO: RUNNNNNNINNGGGGG!

1 GETTING STARTED

2 GOALS

3 CONFIDENCE

4 ANXIETY AND EXERTION

5 PREPPING

6 LET’S GO RUNNING

7 YOU DID IT!

8 PANIC VS. PUFF

9 GETTING TO KNOW YOUR BODY

10 HABIT

11 NOW WHAT?

12 THE DIFFICULT SECOND WEEK

13 DIFFERENT WAYS OF RUNNING

14 WHAT TO LISTEN TO

15 ON THE WAY TO 5K

16 BOREDOM

17 LONGER-TERM MOTIVATION

18 WHAT COMES NEXT

19 SCARING YOURSELF ON PURPOSE

20 PITFALLS

21 BEING PROUD

FOOTNOTE

END NOTES

RESOURCES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY BELLA MACKIE

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

Hello. Welcome to my diary – where I’ll be writing down my innermost secrets and talking about boys I fancy.

Oh no, wait, this isn’t that kind of journal. This is a journal for YOU. And while you’re welcome to write about boys (or girls) as much as you want in it, I’ll be focusing more on mental health and how running might be able to help you. Some of you will know that I wrote a book called Jog On – some of you might have read it. It’s OK if you haven’t (but, y’know, feel free to pick up a copy, my dog needs to be kept in bones) because this journal will hopefully be a space for those who read the book AND for those who didn’t but still would like to know more about the link between mental health and going for a jog.

Jog On is a book I wrote about my experience with anxiety – a horrible condition which makes life feel incredibly scary and can leave you feeling unable to cope with the everyday. I wrote it to show other sufferers that they are not alone, and to promote jogging as one tool to help with such issues. For me, running made me feel stronger than I ever had, it gave me back some independence (which mental illness often robs from you) and it showed me how strong the link between my brain and my body is – a link I think we often ignore in the modern world.

In five years of running, I’ve stopped having the panic attacks which paralysed me. I’ve been able to go to places that my anxious brain would’ve prevented me from visiting. I’ve taken on challenges that I would’ve hidden away, and I’ve graduated from a life half lived to one that feels full and exciting – not tinged with fear and endless panic. I still have moments of anxiety and low mood – after all, running is not a cure-all (nothing is) – but I’m mostly able to dig myself out of these moments now, and for that, I credit my daily jogs. I can draw a direct line from that first short run I took to where I am now, and I’m far from the only person to feel this way. As the legendary runner and author George Sheehan once said: ‘The obsession with running is really an obsession with the potential for more and more life.’[1]

The response to Jog On was bigger and more emotional than I could ever have dreamed. I wrote it honestly and openly, hoping that it might help a few people and make my family understand my brain a bit better. But it ended up being a best-seller, and I’ve had thousands of messages from people who read it, either telling me about their own battles with mental health or asking for tips about how to get into running. It made me realise that one person being really honest about their mental health can produce a knock-on effect. Being blunt about my weirdest thoughts and scariest moments seemed to help other people open up and talk about theirs. It’s a hard thing to do – especially when you feel as though other people will judge you or recoil. But it’s really the only way to shrug off the long-held stigma surrounding mental illness and – more importantly – it’s the only way to help yourself. It’s nice being alive at a time in history when we’re dismantling the traditional stereotypes about mental health, but it’s even nicer being able to feel like you can tell an employer, a loved one or a doctor about what you’re going through without fear of mockery or anger.

Despite knowing how important it is to open up to others when we’re feeling low or worried, sometimes it’s still hard to actually do it. I told parts of my story to different people for years – shading in bits and holding back certain details depending on what I felt the other person could handle. And sometimes you just want to have a place to talk about this stuff without having to manage another person’s expectations. So this journal will be an honest place to do that. A space to learn a bit more about mental health, somewhere to start or further your running journey, a place to reassess what you want from running and, most importantly, a home for all the thoughts you want to get out.

There’s a good reason that people have kept diaries for centuries. Though he was far from the first, Samuel Pepys is probably the most well-known diarist.[2] He jotted his thoughts down for ten years between 1660 and 1669 and wrote over a million words – many about his mistresses. (Maybe it assuaged a guilty conscience. If it did, he hid it well.) Cognitive behavioural therapy also encourages the subject to write down their thoughts – a form of brain homework if you like. More on that later.

Pepys might not have made the link between his obsessive record keeping and his own mental health but modern research has. Brain scans have shown a change in the amygdala – the part of the brain responsible for processing our emotions – when we put pen to paper about our worries.[3] Studies have even shown us that writing down our negative thoughts and emotions might help our physical health – prompting fewer trips to the GP and leading to less time off work.[4]

Think of it like a Pensieve (if you’ve not read Harry Potter then firstly, wow, and also, a Pensieve is a stone dish you can put your memories in when you feel like your mind is overflowing with them) – somewhere to offload the stuff that’s worrying you and look at it from a place slightly removed.[5] A thought whirring around your mind gets gloopy and collects detritus as it goes round and round, making it hard to rationalise. But by looking at the thought summed up on paper, we’re able to see it more clearly and – hopefully – let go of the anxiety around it.

I received so many questions from readers when Jog On came out, questions about running, about panic attacks, about how to motivate yourself when it feels impossible, about the best running trainers and even about what ice cream I eat after a jog. So many of these queries will be addressed in the coming chapters – because there’s nothing better than a gaggle of avid readers to tell you what’s important and what you’ve missed. It’s been like free market research and I’m so glad of it. Lastly, I am not in the business of motivational quotes or cheery platitudes. I still struggle from time to time – I don’t live amongst glitter and rainbows.

So this might be a touch more cynical than some journals – but if that’s your thing, then welcome to your running and mental health journal.

One last note – since I’ve tried to tie together advice on running and discussion of mental health, I’ve decided that this journal will alternate between the two. Obviously the sections will merge in lots of places, but I think it’s helpful to concentrate solely on mental health in some places – after all, what’s more important? And equally, when we’re talking about running shoes or how to prevent injury, I’d like you to be focusing on that without getting bogged down in symptoms about anxiety. But you can’t understand why running helps boost mood unless we also look at the times when your mental health is suffering. Also, feel free to read just the running parts or just the mental stuff if that’s what you want to do. My mum read only the peace bits of War and Peace. She is excellent.

PART ONE

GETTING HELP

This journal talks a lot about mental health – which covers a HUGE range of issues. I’m going to mainly talk about anxiety because that’s my wheelhouse (I would smash Mastermind if excessive worry was my specialist subject), but that itself is an umbrella term. And mental-health issues often overlap, so I think that you’ll recognise much of this stuff whether you suffer from OCD, social anxiety or panic attacks. All of us afflicted with anxiety speak the same language. And that’s true of runners too. And anxious runners are even more in sync with each other. When I do talks, there’s usually a book signing at the end, and I usually ask people whether they’re anxious, a runner or an anxious runner. Because those are my people. They’re not coming to see me because they love poetry and fine dining. I assume you’re here because you’re also in one of those three tribes (you can like poetry and food too, of course).

First things first. If you’re struggling with your brain and haven’t sought help – go and speak to your GP. This book – NO book – can do more for you than talking to a professional who can help you with diagnosis, therapy, medication and support. It’s hard. A 2004 study by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that between 30 and 80 per cent of people with a mental-health issue don’t seek treatment – and the reasons why vary.[1] If you’ve not sought any help, circle the explanation(s) that fit this best:

Shame

A feeling that you’re not worth help

A sense that nothing can make you feel better

Not knowing where to go

Not feeling confident that your story will be confidential

A worry that you can’t access or afford treatment

A feeling that you won’t be taken seriously

A bad experience with a GP or other medical professional

You want to handle it alone

If your reason isn’t listed, write it in the space below.

I understand all of these concerns, by the way – I’ve felt nearly all of them myself. But here’s the thing: mental illness will not go away on its own, and the longer it continues, the harder it can be to treat. We know that many mental-health conditions manifest in adolescence, and calcify over time. If you seek help you could:

• Lower your risk of further incidents down the road.

• Reduce career and life disruption.

• Remove the need for longer treatment or hospitalisation.

• Gain the tools to help you cope with future stressful periods.

• Learn how to talk to loved ones about how you’re feeling.

If that all seems a bit clinical, what if I told you that getting help might make you feel BETTER, see glimmers of hope and no longer have to shoulder the burden of worry and panic and sadness?

Write down what you’d most like to achieve with some help – for me it was reducing panic attacks and loosening the grip that intrusive ‘what if’ thoughts had on my brain. Yours might be feeling happier, or reducing obsessions, or being able to go on planes.

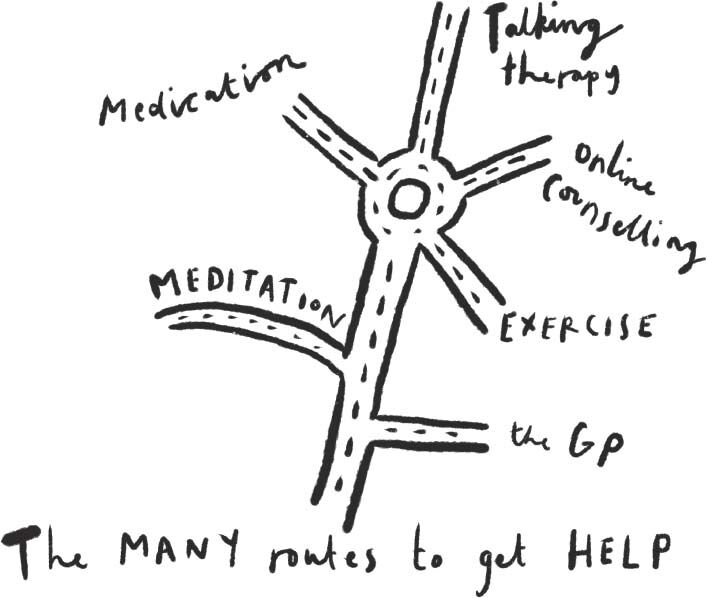

Seeking professional help for the first time can feel daunting and as though you’re not in control. So it might be helpful to keep one or two things in mind. If you’re nervous about going to your GP, consider taking a friend to hold your hand and, most importantly, remember that doctors see people who are struggling mentally EVERY DAY. One in four people are said to experience some mental-health problems in their lifetime, and your doctor is on the frontline of initial treatment. The other thing to say is that if you don’t feel satisfied with the help you’re offered then ask for a different doctor or enquire about other services on offer. Look, it happens, some doctors aren’t fully au fait with mental-health problems, just like some employers aren’t and some mothers. But their numbers are shrinking and you have every right to sensitive and humane treatment. So if it’s not working for you, don’t lose heart, just try a different tack.

That probably sounded a bit bossy. But it’s important to speak to a professional about mental health first of all. There are so many people out there pushing wacky cures for anxiety and depression, and they normally do absolutely nothing to help people. But desperate people are prone to try anything – I once bought a VERY expensive set of vitamins that online testimonials promised would cure my anxiety. They didn’t even make my hair shiny.

PART TWO

THE ANXIETY UMBRELLA

Anxiety is a mother-fucker. It’s not mild niggles about a work task or a slight panic about the iron having been left on. It’s all-encompassing – a worry about a work task multiplies, mushrooms and becomes all you can focus on. A vague unease in crowds can end up in panic attacks that feel like you’re going to die. A passing thought about germs can end up in an obsession about cleaning. Your brain is on high alert for danger all the time. This is not the same as fear, which is in response to an obvious threat. Anxiety is about future and imagined dangers – most of them enlarged, unrealistic and twisted beyond recognition. Everyone has felt anxious at some point in their lives, but most people don’t become consumed by it. Lucky them.

I’m going to give you some personal examples because sharing is caring and I always feel relieved when I hear about other people’s experiences (it makes me feel less alone).

Here are two small examples of my anxious brain – the scale of these episodes differs greatly but both were incredibly distressing:

I am on holiday and I walk across some grass. I feel a sting on the sole of my foot and look down to see a wasp. Immediately, I panic. My brain flies straight to the certain knowledge that I will develop anaphylactic shock from this sting. I can’t breathe – it’s happening fast. I run to the house, and I can feel my lips swelling up, my lungs constricting. I’m clawing at my throat, desperate to get some air in but I can’t and we’re miles away from help. I signal to my family – frantically trying to make them understand that I’m no longer able to breathe as they try and calm me down. I lie down on the bed as my mum strokes my hair and I wait for death. But ten minutes later I am forced to concede that what I thought was an allergic reaction was a panic attack brought on by my powerfully anxious brain. I’m so wiped out by it, and so embarrassed and sad that this is where my mind goes, that I have to have a two-hour nap. That fear of anaphylaxis stayed with me for a further two years. I wasn’t twelve by the way, I was twenty-nine.

Can you think of a time when your anxiety went from zero to a hundred in seconds? It’s good to get it out – I can look back and laugh about it (a bit) now and the more I tell people these stories, the less powerful they seem. No, the less powerful they ARE.

Right, scenario number two:

I am at college and the bus journey was a bit weird, I felt hot and dizzy and things felt ‘off’. When I get to the building, I feel ill and scared and everything looks weird. I panic – but not about anything in particular and that feels even scarier. I make my excuses and leave to go home. That night my head spins as I try to get my brain around why I felt so strange. I tie myself in knots as I explore stranger and more irrational paths trying to make sense of what I’m experiencing. It’s overwhelming doom mixed with a feeling that everything is unreal. And I have no blueprint for that. Eventually I settle on the answer: I must be going mad. Mad like you hear about on Crimewatch. Mad like killers in movies. And it clicks – I am psychotic. I have no proof of this, but that’s where my mind has landed. From that day, I become obsessed with monitoring my ‘mad’ behaviour. I pick apart every thought that pops into my mind – am I paranoid? Did I just think someone was watching me? Do I hear voices? The exhaustion from trying to push back against these thoughts is overwhelming and, on top of all the thoughts which keep coming, I’m experiencing a million physical side effects of anxiety too – adrenaline courses through my body, I feel sick constantly, I can’t sleep, I can’t eat. The mental and physical go hand in hand and egg each other on – it’s a vicious cycle.

This one was an even lower moment in my life, but the two stories have a couple of strong similarities. Can you spot them? No, I’m kidding, you’re not eight and this isn’t Where’s Wally. I’ll tell you:

Catastrophic thinking – my mind (and maybe yours since you’re here) has the amazing ability to go from zero to a hundred in two seconds flat. And it’s never a positive destination. The only places my mind goes are dark and scary. Catastrophic thinking can be described as your brain searching for the worst-case scenario. It might seem like a self-defence mechanism – ‘Prepare for the worst, be pleasantly surprised’ – but it actually kick-starts an anxiety loop. You think about the worst scenario and your brain and body produce a reaction like the one you’d have if that actual scenario was happening. So I imagine I’m in serious medical danger, or feel like I’m going mad, and I panic. Adrenaline floods me, I’m tearful, I can’t breathe and I think the world is ending. When it doesn’t, I don’t pick myself up and feel exhilarated that I’m all safe. I feel wiped out and scared for the next time I feel worries like this. This can make you feel like there’s no point in feeling hopeful about the future or lead to you skipping situations that produce catastrophic thoughts – thereby feeding the loop and reinforcing this thought pattern.

An inability to self-soothe. No, I’m not a baby and yes, this description is slightly grim, but it’s also kind of spot on. In both these cases, I couldn’t pull myself back from panic. I didn’t push back against the thoughts or calm my body down. I was washed away with the fear, and let it take over. That’s natural, your mind tells you there’s something to worry about and so you listen. It’s a primal thing – this fight-or-flight instinct – but with anxiety, you have to learn that your instincts are often wrong. And that’s a hard one to realise – that sometimes your brain and body are working against your best interests. But it’s a vital thing to learn – because understanding the difference between real dangers and imagined ones will eventually help stop your mind seeing dangers everywhere and help you decide whether a worry is worth engaging with or not.