Полная версия

My Week With Marilyn

My Week

with Marilyn

The Prince, the Showgirl and Me

My Week with Marilyn

Colin Clark

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

The Prince, the Showgirl and Me

Dedication

Illustrations

Preface

The Prince and the Showgirl

Production Crew

The Diaries

Postscript

My Week with Marilyn

Dedication

Introduction

Tuesday, 11 September 1956

Wednesday, 12 September

Thursday, 13 September

Friday, 14 September

Saturday, 15 September

Sunday, 16 September

Monday, 17 September

Tuesday, 18 September

Wednesday, 19 September

Postscript

Appendix

Resurrecting Marilyn

Picture Section

About the Author

Praise for Colin Clark

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

By Simon Curtis, Director of My Week with Marilyn

‘A fairy story, an interlude, an episode out of time and space which nevertheless was real’ is how Colin Clark describes his account of working on The Prince and the Showgirl. He published his first diary of his experiences, The Prince, the Showgirl and Me, in 1995 and in it he invites the reader to share his excitement as he gets closer and closer to the inner sanctum of the business and witnesses the complex process of a film being made. I loved the diary from the moment I first read it and was drawn both to the compelling detail of the making of a film in 1956 but also to the magical fantasy of a young man having an intimate relationship with Marilyn Monroe at the height of her powers on his very first job. Since my first job was as an unpaid assistant director on a theatre production of Measure for Measure during which I worked closely with its leading lady Helen Mirren, running errands for her and helping her with her lines, I was familiar with the territory that Colin was in.

Of course, this was no ordinary film – Marilyn Monroe had bought the rights to Rattigan’s play The Sleeping Prince under the auspices of her newly formed production company (Marilyn was far ahead of her time in that way). She hoped she could control her destiny by becoming a producer and looked forward to working with the great Olivier. He, in turn, was not only prepared to work with her in place of his wife Vivien Leigh, who had played the same part opposite him on stage, but hoped that working with the biggest movie star in the world would rejuvenate his career. I believe he also hoped for a romance with Marilyn but she arrived in London on the arm of her brand new husband Arthur Miller so that became unlikely.

It is hard not to see Olivier, then aged 50, as emblematic of fading Britain and Marilyn, aged 30, as the poster girl for brash, new America. 1956 was a seminal year in English culture – the year of Look Back in Anger and Lucky Jim, the birth of rock and roll and commercial television. It was the moment England finally shook itself from under the shadow of World War Two. Unfortunately The Sleeping Prince, for all its charm, belonged to the old theatrical tradition and, surprisingly for Marilyn, who wanted to break into roles more challenging than ditzy blondes, her part of Elsie is a giggly chorus girl.

The culture clash between these two icons is evident right from the start and Colin has a ringside seat for it all. He is amazed to watch the struggle for common ground between Marilyn, now devoted to The Method (a way of acting in which actors internalised, rather than simulated, the feelings of their character) and always accompanied by her coach Paula Strasberg, and Olivier who believed in a more external way of working. Rattigan’s play had worked on a West End stage, when it cashed in on the excitement generated by the Queen’s coronation, but it was hardly bursting with cinematic potential. Colin gets it right when he describes himself telling Marilyn, in a remarkably bold and perceptive moment, ‘We are all trying to make a film which absolutely should not be made.’

I was entranced by Colin’s first diary but it was the publication of the second, My Week with Marilyn, in 2000 that convinced me that there was a film to be made by combining the two. In the second volume Colin at last reveals his secret: during the making of the film, when Arthur Miller has left the country, he and Marilyn have a remarkably intimate week together. She finds herself able to trust Colin and, for the first time in a life of romancing powerful older men, she is drawn to someone younger than she is. Theirs is not a passionate sexual affair but an erotically charged connection of great intimacy. Colin longs to rescue her from her entourage and a life fuelled by pills and alcohol (‘I desperately wanted to save her but what could I do?’) but it is enough for Marilyn that he is a trusted friend who listens and does not take advantage of her as men usually do.

For all my passion for the material, it was a long seven years before the first day of filming and we would never have got there at all without Michelle Williams and Ken Branagh committing to play Marilyn and Olivier. I still cannot believe my luck that two such magnificent actors were courageously prepared to take on these iconic roles. They both bring fierce intelligence and detail to all their performances and I learned from each of them every day. Our production was based at Pinewood Studios where The Prince and the Showgirl had been made and on her first day Michelle was put in Marilyn’s old dressing room. We filmed on the same stage as they had and it was a magical moment to witness Michelle recreating Marilyn’s dance from the film in Donal Woods’s recreation of the original sets.

We tried to film at the authentic locations and unusually gained access to Eton College and Windsor Castle. I was particularly excited to be at Parkside, the house the newlywed Millers had rented whilst in England. We filmed Colin observing an emotional Marilyn sitting on the stairs after discovering Arthur’s journal in the exact spot it had actually taken place.

In some ways the film plays as a love letter to a lost England and all of us working on it paid great attention to detail. There was so much reference material for us to look at and Colin’s books were the best source of all. His tone of voice guided me and his portrait of Marilyn as a very bright woman who, despite her troubled childhood, was trying to make the best of her life was important. Thanks to Colin’s insights, I saw her as an ambitious actress, desperate to be taken seriously, struggling with a very thin part. She was not helped by a director who insisted on working in a way that made her uncomfortable.

I admire Lord Olivier very much and remember seeing him towards the end of his life at the opening of the National Theatre. He was scathing of Marilyn’s performance whilst they were making the film but later generously acknowledged how much the camera loved her and came to see how very good she actually was.

Marilyn had come to England with such high hopes. She was newly married to Miller, a producer apparently in control of her own destiny and about to work with the greats of British theatre. The sadness of our story is how each of her dreams collapsed during the making of the film. Her marriage lasted a few more years and sadly she was only to live six more years.

I regret that I never met Colin Clark but I am truly honoured to have made the film of his two diaries. I am grateful for the support of his family and delighted that on their visits to the set they appeared to recognise and admire Eddie Redmayne’s excellent performance as ‘Colin’. I have taken a cue for what we have done from the tone of Colin’s wonderful books and hope very much he would have liked the film we have made.

The Prince, the Showgirl and Me

Dedication

For Christopher and Helena,

with love

Illustrations

Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller arrive at Heathrow, escorted by my friends, the policemen. (© Press Association Images)

Crowds of reporters force MM and SLO to take refuge behind a counter at Heathrow. (© Mirrorpix)

Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh greet MM and AM at the airport. (© Getty Images)

AM, MM and SLO on arrival at Parkside House. My head can just be seen through the window. (© Popperfoto/Getty Images)

MM, standing between Victor Mature and Anthony Quayle, meets the Queen at the Royal Film Premiere of The Battle of the River Plate. MM and HM were almost exactly the same age. (© Popperfoto/Getty Images)

I was given the job of third assistant director on The Prince and the Showgirl because my parents were friends of Laurence Olivier.

Vivien Leigh and SLO in The Sleeping Prince, Phoenix Theatre, 1953. (© Popperfoto/Getty Images)

MM at the start of filming. (© Milton H. Greene Collection © 2011 Joshua Greene www.archiveimages.com)

Roger Furse’s original design for the salon, much changed for the actual filming. (British Film Institute)

Production unit photograph of The Prince and the Showgirl. (British Film Institute)

Marilyn at the London first night of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge. (© 2011 Getty Images)

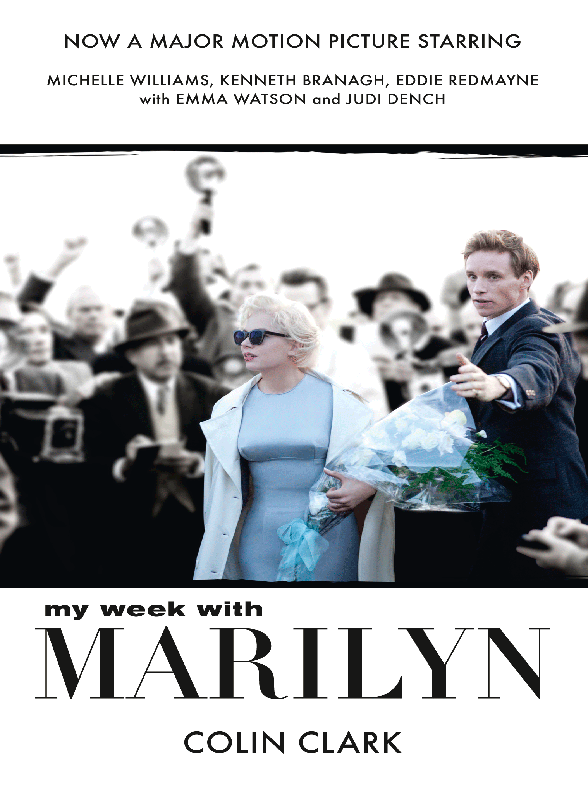

All images listed below © The Weinstein Company

Dougray Scott and Michelle Williams, as Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe, arrive in London.

Dougray Scott, Michelle Williams, Kenneth Branagh as Sir Laurence Olivier and Julia Ormond as Vivien Leigh, on arrival at Parkside House.

Director Simon Curtis talks to Eddie Redmayne on set.

Elsie Marina, played by Monroe, was the female lead in The Prince and the Showgirl. Here, Michelle Williams re-enacts Elsie’s dance in the purple sitting room.

Echoing the classic photograph taken at the start of filming The Sleeping Prince.

Kenneth Branagh as Sir Laurence Olivier. The clashes between him and Monroe entered film legend.

Simon Curtis, Dominic Cooper as Milton Greene, Dougray Scott and producer David Parfitt taking a break on set.

Michelle Williams capturing a classic Monroe pose.

Michelle Williams as Monroe, the icon.

Eddie Redmayne as Colin Clark, leading Monroe and Miller away from the paparazzi.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future editions.

Preface

In 1943, when I was ten years old, my boarding school decided that my class should see Gone with the Wind. Film shows were a monthly treat then, and we had already seen several stirring black-and-white wartime epics, but Gone with the Wind was different. It was in colour, it was very long, and it contained some gruesome scenes of wounded soldiers, the sort of thing which was obviously never included in British films of the time. Our teacher took great trouble to explain to us that the film was just an illusion, made up of clever special effects. Nevertheless, watching it in that bare school hall had a dramatic effect on all of us.

At about the same time my father, Kenneth Clark, had been made controller of home publicity at the Ministry of Information. This meant that he was responsible for extricating British actors and actresses from the armed forces so that they could work in patriotic films. He made frequent visits to the studios around London to see how they were getting on, and I persuaded him to let me come too. His principal ally was Alexander Korda, who was the most powerful British producer at the time, and whom my father had persuaded to join in the ‘war effort’. Through him my father and mother met all the stars of the film world. Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh became their close friends, and William Walton, who was composing the music for Olivier’s Henry V, was made my godfather to replace the original one who had been killed by a bomb. Another Hungarian producer, Gabriel Pascal, had managed to persuade George Bernard Shaw to let him have the film rights to all his plays. He came to our house in Hampstead with a beautiful young American actress called Irene Worth, and promised to buy me a pair of white peacocks if I would act for him, offering me the part of Ptolemy in his production of Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra (with Vivien Leigh). My parents said no, but I was not the least bit disappointed: I knew that I could never be an actor, and I also knew that those white peacocks were as much a product of Pascal’s imagination as Caesar and Cleopatra was of Shaw’s.

I had become completely fascinated by the concept of a fictional idea being made into a real film, which is in itself an illusion. It is a fascination which I have never lost. At the age of twelve I explained this to my father, and told him of my determination to be a film director. My only worry was that all the directors I had met were fat and ugly. To my surprise he took me seriously. Although he was involved in all the performing arts – opera, ballet and theatre as well as film – his main love was painting. He pointed out that painting contains the same elements of illusion and reality as film, and that Michael Powell and David Lean were both successful directors, and they were thin.

From then on, a visit to a film set was like a dream fulfilled. I saw Noël Coward in a tank of oily black water making In Which We Serve; I saw Vivien Leigh being carried on a very wobbly litter in front of a plaster Sphinx on the set of Caesar and Cleopatra; I saw her again in Anna Karenina – she had offered me the role of her son, again refused; and many more. I was not in love with the magic of film the way many children are with theatre or ballet: I was in love with the way in which that magic was made.

When I got to Eton in 1946 it became clear that I had chosen a pretty eccentric path. ‘Art’ did not then have the respectable connotations that it does today. My family, though wealthy enough, was as far from the typical ‘hunting, shooting and fishing’ set as it was possible to be. None of my more conventional contemporaries had ever heard of an art historian, and I was forced to describe my father as a professor (he had been Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford). My friends could not understand me at all – many still can’t – and as if to underline the difference between us, I chose to be a pilot in the RAF during my National Service rather than to go into the Guards, and then to get a job as a keeper at London Zoo rather than work in a merchant bank.

In the summer of 1952, while on vacation from Oxford, I went on a motoring tour of Europe and found myself stranded in a little palace in the mountains of north Portugal. It belonged to an Englishman called Peter Pitt-Millward, and apart from his occasional guests, I had no one else with whom to converse for over two months. To make things worse, I fell passionately in love with someone who could speak nothing but Portuguese. I could not even confide in Peter about this as he was also in love – with the same person. So I started to keep a daily journal in which I could explore my emotions, and my loneliness. This feeling of isolation persisted throughout the remainder of my time at university.

By the time I got the job on The Prince and the Showgirl in 1956, my diary had become a firm friend. However tired I was, I could not sleep before I had written down some of the things that had happened during the day, and confided some of the opinions that I had not dared to express to anyone, scribbling away in an old ledger which I kept wrapped up in my pyjamas. I did not always get things right, and as I never expected anyone else to read what I had written, I had no need to be what we now call ‘politically correct’. Even so, in this published version of my diary for June to November 1956, I have cut very little out. I was a well-brought-up boy, and when you see ‘f—’ in this book it is because I wrote ‘f—’ in my diary.

When the filming of The Prince and the Showgirl was over, it was many, many years before I dared to read my diary of that time again, just as it was many, many years before I could bring myself to see the film in a cinema. Even now I have trouble seeing past the pain and anxiety in Marilyn Monroe’s eyes.

This book is really all about Marilyn. For five months, whether she turned up or not, she dominated our every waking thought. I was the least important person in the whole studio, but I was in a wonderful position from which to observe. The Third Assistant Director is really a kind of superior messenger boy. I got to meet everyone and go everywhere, unencumbered by responsibilities which might tie me down, or narrow my viewpoint. No one can feel threatened by a 3rd Ast Dir (except perhaps the ‘extras’, who he has to keep under control), and most of the people involved in making the film felt they could be more open with me than with a possible rival. When the filming was completed I was almost the only person who was still on speaking terms with everyone else. That alone probably makes this diary unique.

The Prince and the Showgirl

Cast List

ELSIE MARINA Marilyn Monroe

THE REGENT OF CARPATHIA Laurence Olivier

THE QUEEN DOWAGER Sybil Thorndike

MR NORTHBROOK Richard Wattis

THE KING OF CARPATHIA Jeremy Spenser

MAJOR DOMO Paul Hardwick

MAISIE SPRINGFIELD Jean Kent

LADY SUNNINGDALE Maxine Audley

FANNY Daphne Anderson

BETTY Vera Day

MAGGIE Gillian Owen

FOREIGN OFFICE MINISTER David Horne

THEATRE DRESSER Gladys Henson

HOFFMAN Esmond Knight

LADIES-IN-WAITING Rosamund Greenwood Margot Lister

VALETS Dennis Edwards Andrea Melandrinos

Production Crew

PRODUCER AND DIRECTOR Laurence Olivier

EXECUTIVE IN CHARGE OF Hugh Perceval

PRODUCTION

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Milton Greene

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Anthony Bushell

FIRST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR David Orton

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Jack Cardiff

PRODUCTION DESIGNER Roger Furse

PRODUCTION MANAGER Teddy Joseph

ART DIRECTION Carmen Dillon

EDITOR Jack Harris

CONTINUITY Elaine Schreyck

CAMERA OPERATOR Denys Coop

SOUND RECORDISTS John Mitchell Gordon McCallum

LADIES’ COSTUMES Beatrice Dawson

MAKE-UP Toni Sforzini

HAIRDRESSING Gordon Bond

SET DRESSER Dario Simoni

SCREENPLAY Terence Rattigan

MUSIC COMPOSED BY Richard Addinsell

DANCES ARRANGED BY William Chappell

The Diaries

SUNDAY, 3 JUNE 1956

Now that University is behind me, I’m going to get a job – a real job on a real film. At 9 a.m. tomorrow I will be at Laurence Olivier’s film company to offer my services on his next production. The papers say it will star Marilyn Monroe, so it should be exciting.

Two weeks ago, Larry and Vivien came down to stay at Saltwood1 for the weekend. Mama told Vivien that I wanted to be a film director. I was mortified, but Vivien just gave a great purr and said ‘Larry will give Colin a job, won’t you Larry darling!’ I could see Larry groan under his breath. ‘Go and see Hugh Perceval at 146 Piccadilly,’ he said. ‘He might have something.’

So that is where I have an appointment in the morning. And every night I am going to write this diary. It could be fun to look back on, when I am old and famous!

MONDAY, 4 JUNE

This is going to be really hard. I know absolutely nothing about making films. I’m totally ignorant. Did I really think they were actually shooting a film in Piccadilly?

At 10 a.m. I turned up at the office of Laurence Olivier Productions, punctual and sober.

The offices themselves are very few. A large luxurious reception area with sofas, a secretary’s office at the far end, and Mr Perceval’s office leading off that. It is clearly the ground floor of what was once a private house. The secretary, friendly but detached – would I wait. Mr Perceval was on the phone. Soon I was ushered in, anxious now. There didn’t seem to be enough going on. Mr P is a tall, thin, gloomy man with black-rim spectacles. His sparse black hair is brushed back and he has a black moustache. He puffs a pipe continually.

‘Yes. What do you want?’ (No introductions whatever.)

‘I want a job on the Marilyn Monroe film.’

‘Oh, ho, you do? What as?’

‘Anything.’

I suppose he could see that I was a complete fool and he softened a little.

‘Well. We don’t start filming for eight weeks. You really should come back then. At the moment we have no more offices than you can see here, and no jobs. I only have my chauffeur and my secretary. I am afraid I misunderstood Laurence. I thought you were coming to interview me about the film.’

Blind panic set in. I must say something.

‘Can I wait here until there is a job?’

‘For eight weeks??’

‘In the waiting room – in case something comes up?’

‘Grmph.’ Very gloomy, and bored now. ‘It’s a free country, I suppose. But I’m telling you, it’s going to be eight weeks. And then I can’t promise anything.’

Gets up and opens door.

‘Good day.’

I went out and sat down on one of the sofas in the waiting room. The secretary gave me a very cold look. She’s quite pretty, but is certainly not flirtatious.

I just didn’t know what to do. I had expected huge offices, even studios, lots of work going on – willing hands needed in every department, and a bit like the London Zoo when I turned up there and asked for a job as a keeper in ’53 (and got one!2).

So I just sat and waited.

At lunchtime I was saved by a friendly face. Gilman, Larry and Vivien’s chauffeur came in, brash and cockney as ever.

‘’Ullo Colin. What you doin’ ’ere?’

I explained.

‘Hmm. There’s no work here. I’ve got to get his nibs’ lunch. Come and have a drink in the pub.’

I went gratefully (but only ½ of bitter). Gilman told me what was going on. He was on loan to Perceval. Every morning he did errands, for Perceval or for Larry, and then came back here to get Perceval’s lunch. This never varied: two cheese rolls and a Guinness.

‘You won’t get work from him, Colin. Miserable bugger.’

‘Well, I’ve got nothing else in the world to do but wait, so I might as well wait.’

‘OK. Good luck. We can always have a pint together at lunchtime.’

We went back with Mr P’s sandwiches and drink and Gilman sped off in the Bentley. I waited until 6 p.m., when they all packed up and left.

‘Night all,’ said Mr P gloomily, without a glance at me. I had a large brandy and water in the pub. I’ll be back in the office tomorrow.

TUESDAY, 5 JUNE

I was there at 8.30. The secretary arrived at 8.55. Mr P punctually at nine. He just gave me a grim stare as he came in. Then he gets on the phone and stays there most of the day. He never smiles and he never raises his voice. The secretary gets the calls for him and then taps away at the typewriter. She is polite but not friendly. She treats me like a client. I wonder if she knows that ‘M and D’3 are friends of Larry and Vivien?

She went to lunch at 12.30 with her handbag and gloves. Gilman arrived at 12.45. Then we went to the pub, and got back with Mr P’s lunch at 1.15. I wonder if this is a regular situation. Maybe I can make something out of it. Mr P grumbles at the delay but Gilman is irrepressible.

Vivien had told me why she had hired Gilman. He was a relief driver, sent along when their old chauffeur was ill. On the first day, as he drove her and Larry down Bond Street, he suddenly slammed on the brakes. ‘Cor. Look, what a lovely waistcoat!’ he cried, pointing to a very exclusive man’s-shop window. Vivien adores that sort of unspoilt character and hired him on the spot. Needless to say he now worships both of them, and is fanatically loyal. He is a Barnardo boy and very tough, so Larry probably thinks he is a good bodyguard for Vivien too. He certainly is a good pal to me and saves my life when he appears.