Полная версия

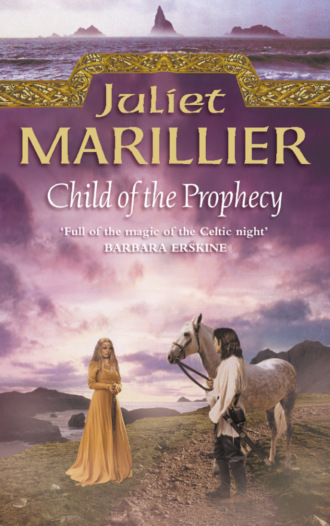

Child of the Prophecy

‘I – yes, Father.’

‘Good.’ He gave a nod. ‘Stand here by me. Look into the mirror. Watch my face.’

The surface was bronze, polished to a bright reflective sheen. Our images showed side by side; the same face with subtle alterations. The dark red curls; the fierce eyes, dark as ripe berries; the pale unfreckled skin. My father’s countenance was handsome enough, I thought, if somewhat forbidding in expression. Mine was a child’s, unformed, plain, a little pudding of a face. I scowled at my reflection, and glanced back at my father in the mirror. I sucked in my breath.

My father’s face was changing. The nose grew hooked, the deep red hair frosted with white, the skin wrinkled and blotched like an ancient apple left too long in store. I stared, aghast. He raised a hand, and it was an old man’s hand, gnarled and knotted, with nails like the claws of some feral creature. I could not tear my eyes away from the mirrored image.

‘Now look at me,’ he said quietly, and the voice was his own. I forced my eyes to flicker sideways, though my heart shrank at the thought that the man standing by me might be this wizened husk of my fine, upright father. And there he was, the same as ever, dark eyes fixed on mine, hair still curling glossily auburn about his temples. I turned back to the mirror.

The face was changing again. It wavered for a moment, and stilled. This time the difference was more subtle. The hair a shade lighter, a touch straighter. The eyes a deep blue, not the unusual shade of dark purple my father and I shared. The shoulders somewhat broader, the height a handspan greater, the nose and chin with a touch of coarseness not seen there before. It was my father still; and yet, it was a different man.

‘This time,’ he said, ‘when you take your eyes from the mirror, you will see what I want you to see. Don’t be frightened, Fainne. I am still myself. This is the Glamour, which we use to clothe ourselves for a special purpose. It is a powerful tool if employed adeptly. It is not so much an alteration of one’s appearance, as a shift in others’ perception. The technique must be exercised with extreme caution.’

When I looked, this time, the man at my side was the man in the mirror; my father, and not my father. I blinked, but he remained not himself. My heart was thumping in my chest, and my hands felt clammy.

‘Good,’ said my father quietly. ‘Breathe slowly as I showed you. Deal with your fear and put it aside. This skill is not learned in a day, or a season, or a year. You’ll have to work extremely hard.’

‘Then why didn’t you start teaching me before?’ I managed, still deeply unsettled to see him so changed. It would almost have been easier if he had transformed himself into a dog, or a horse, or a small dragon even; not this – this not quite right version of himself.

‘You were too young before. This is the right age. Now come.’ And suddenly he was himself again, as quick as a snap of the fingers. ‘Step by step. Use the mirror. We’ll start with the eyes. Concentrate, Fainne. Breathe from the belly. Look into the mirror. Look at the point just between the brows. Good. Will your body to utter stillness … put aside the awareness of time passing … I will give you some words to use, at first. In time you must learn to work without the mirror, and without the incantation.’

By dusk I was exhausted, my head hollow as a dry gourd, my body cold and damp with sweat. We rested, seated opposite one another on the stone floor.

‘How can I know,’ I asked him, ‘how can I know what is real, and what an image? How can I know that the way I see you is the true way? You could be an ugly, wrinkled old man clothed in the Glamour of a sorcerer.’

Father nodded, his pale features sombre. ‘You cannot know.’

‘But –’

‘It would be possible for one skilled in the art to sustain this guise for years, if it were necessary. It would be possible for such a one to deceive all. Or almost all. As I said, it is a powerful tool.’

‘Almost all?’

He was silent a moment, then gave a nod. ‘You will not blind another practitioner of our art with this magic. There are three, I think, who will always know your true self: a sorcerer, a seer and an innocent. You look weary, Fainne. Perhaps you should rest, and begin this anew in the morning.’

‘I’m well, Father,’ I said, anxious not to disappoint him. ‘I can go on, truly. I’m stronger than I look.’

Father smiled; a rare sight. That seemed to me a change deeper than any the Glamour could effect; as if it were truly another man I saw, the man he might have been, if fate had treated him more kindly. ‘I forget sometimes how young you are, daughter,’ he said gently. ‘I am a hard taskmaster, am I not?’

‘No, Father,’ I said. My eyes were curiously stinging, as if with tears. ‘I’m strong enough.’

‘Oh, yes,’ he said, his mouth once more severe. ‘I don’t doubt that for a moment. Come then, let’s begin again.’

I was twelve years old, and for a short time I was taller than Darragh. That summer my father didn’t let me out much. When he did give me a brief time for rest, I crept away from the Honeycomb and up the hill, no longer sure if this was allowed, but not prepared to ask permission in case it was refused. Darragh would be waiting for me, practising the pipes as often as not, for Dan had taught him well, and the exercise of his skill was pleasure more than duty. We didn’t explore the caves any more, or walk along the shore looking for shells, or make little fires with twigs. Most of the time we sat in the shadow of the standing stones, or in a hollow near the cliff’s edge, and we talked, and then I went home again with the sweet sound of the pipes arching through the air behind me. I say we talked, but it was usually the way of it that Darragh talked and I listened, content to sit quiet in his company. Besides, what had I to talk about? The things I did were secret, not to be spoken. And increasingly, Darragh’s world was unknown to me, foreign, like some sort of thrilling dream that could never come true.

‘Why doesn’t he take you back to Sevenwaters?’ he asked one day, somewhat incautiously. ‘We’ve been there once or twice, you know. There’s an old auntie of my dad’s still lives there. You’ve got a whole family in those parts: uncles, aunts, cousins by the cartload. They’d make you welcome, I’ve no doubt of it.’

‘Why should he?’ I glared at him, finding any criticism of my father difficult, however indirectly expressed.

‘Because –’ Darragh seemed to struggle for words. ‘Because – well, because that’s the way of it, with families. You grow up together, you do things together, you learn from each other and look after each other and – and –’

‘I have my father. He has me. We don’t need anyone else.’

‘It’s no life,’ Darragh muttered. ‘It’s not a life for a girl.’

‘I’m not a girl, I’m a sorcerer’s daughter,’ I retorted, raising my brows at him. ‘There’s no need for me to go to Sevenwaters. My home is here.’

‘You’re doing it again,’ said Darragh after a moment.

‘What?’

‘That thing you do when you’re angry. Your eyes start glowing, and little flashes of light go through your hair, like flames. Don’t tell me you didn’t know.’

‘Well, then,’ I said, thinking I had better exercise more control over my feelings.

‘Well, what?’

‘Well, that just goes to show. That I’m not just a girl. So you can stop planning my future for me. I can plan it myself.’

‘Uh-huh.’ He did not ask me for details. We sat silent for a while, watching the gulls wheel above the returning curraghs. The sea was dark as slate; there would be a storm before dusk. After a while he started to tell me about the white pony he’d brought down from the hills, and how his dad would be wanting him to sell her for a good price at the horse fair, but Darragh wasn’t sure he could part with her, for there was a rare understanding growing between the two of them. By the time he’d finished telling me I was rapt with attention, and had quite forgotten I was cross with him.

I was fourteen years old, and summer was nearly over. Father was pleased with me, I could see it in his eyes. The Glamour was tricky. It was possible to achieve some spectacular results. My father could turn himself into a different being entirely: a bright-eyed red fox, or a strange wraith-like creature most resembling an attenuated wisp of smoke. He gave me the words for this, but he would not allow me to attempt it. There was a danger in it, if used incautiously. The risk was that one might lack the necessary controls to reverse the spell. There was always the chance that one might never come back to oneself. Besides, Father told me, such a transformation caused a major drain on a sorcerer’s power. The further from one’s true self the semblance was, the more severe the resultant depletion. Say one became a ferocious sea-monster, or an eagle with razor-sharp talons, and then managed the return to oneself. For a while, after that, no exercise of the craft would be possible. It could be as long as a day and a night. During that time the sorcerer would be at his, or her, most vulnerable.

So I was forbidden to try the major variants of the spell, which dealt with non-human forms. But the other, the more subtle changing, that I discovered a talent for. At first it was hard work, leaving me exhausted and shaken. But I applied myself, and in time I could slip the Glamour on and off in the twinkle of an eye. I learned to conceal my weariness.

‘You understand,’ said Father gravely, ‘that what you create is simply a deception of others’ eyes. If your disguise is subtle, just a convenient alteration of yourself, folk will be unaware that things have changed. They will simply wonder why they did not notice, before, how utterly charming you were, or how trustworthy your expression. They will not know that they have been manipulated. And when you change back to yourself, they will not know they ever saw you differently. A complete disguise is another matter. That must be used most carefully. It can create difficulties. It is always best to keep your guise as close as possible to your own form. That way you can slip back easily and regain your strength quickly. Excuse me a moment.’ He turned away from me, suppressing a deep cough.

‘Are you unwell?’ I asked. It was unusual for him to have so much as a sniffle, even in the depths of winter.

‘I’m well, Fainne,’ he said. ‘Don’t fuss. Now remember what I said about the Glamour. If you use the major forms you take a great personal risk.’

‘But I could do it,’ I protested. ‘Change myself into a bird or a serpent. I’m sure I could. Can’t I try, just once?’

Father looked at me. ‘Be glad,’ he said, ‘that you have no need of it. Believe that it is perilous. A spell of last resort.’

It was no longer possible to take time off from my studies. I had scarcely seen the sun all summer, for Father had arranged to have our small supply of bread and fish and vegetables brought up to the Honeycomb by one of the local girls. There was a spring in one of the deep gullies, and it was Father himself who went with a bucket for water now. I stayed inside, working. I was training myself not to care. At first it hurt a lot, knowing Darragh would be out there somewhere looking for me, waiting for me. Later, when he gave up waiting, it hurt even more. I’d escape briefly to a high ledge above the water, a secret place accessible only from inside the vaulted passages of the Honeycomb. From this vantage point you could see the full sweep of the bay, from our end with its sheer cliffs and pounding breakers to the western end, where the far promontory sheltered the scattering of cottages and the bright, untidy camp of the travelling folk. You could see the boys and girls running on the shore, and hear their laughter borne on the breath of the west wind, mingled with the wild voices of sea birds. Darragh was there amongst them, taller now, for he had shot up this last winter away. His dark hair was thrown back from his face by the wind, and his grin was as crooked as ever. There was always a girl hanging around him now, sometimes two or three. One in particular I noticed, a little slip of a thing with skin brown from the sun, and a long plait down her back. Wherever Darragh went she wasn’t far away, white teeth flashing in a smile, hand on her hip, looking. With no good reason at all, I hated her.

The lads used to dive off the rocks down below the Honeycomb, unaware of my presence on the ledge above. They were of an age when a boy believes himself invincible, when every lad is a hero who can slay whatever monsters cross his path. The ledge they chose was narrow and slippery; the sea below dark, chill and treacherous. The dive must be calculated to the instant to avoid catching the force of an incoming wave that would crush you against the jagged rocks at the Honeycomb’s base. Again and again they did it, three or four of them, waiting for the moment, bare feet gripping the rock, bodies nut-brown in the sun, while the girls and the smaller children stood watching from the shore, silent in anticipation. Then, sudden and shocking no matter how often repeated, the plunge to the forbidding waters below.

Twice or three times that summer I saw them. The last time I went there, I saw Darragh leave the ledge and climb higher, nimble as a crab on the crevices of the stark cliffside, scrambling up to perch on the tiniest foothold far above the diving point. I caught my breath in shock. He could not intend – surely he did not intend –? I bit my lip and tasted salt blood; I screwed my hands into fists so tight my nails cut my palms. The fool. Why would he try such a thing? How could he possibly –?

He stood poised there a moment as his audience hushed and froze, feeling no doubt some of the same fascinated terror that gripped me. Far, far below the waves crashed and sucked, and far above the gulls screamed a warning. Darragh did not raise his arms for a dive. He simply leaned forward and plummeted down headfirst, straight as an arrow, hands by his sides, down and down until his body entered the water as neatly as a gannet diving for fish; and I watched one great wave wash over the spot where he had vanished, and another, and a third, while my heart hammered with fear, and then, much further in towards the shore, a sleek dark head emerged from the water and he began to swim, and a cheer went up from the boys on the ledge and the girls on the sand, and when he came out of the water, dripping, laughing, she was there to greet him and to offer him the shawl from her own shoulders to dry himself off with.

I did not concentrate very well that day, and Father gave me a sharp look, but said nothing. It was my own choice not to go back and watch them after that. What Father had taught me was right. A sorcerer, or a sorcerer’s daughter, could not perform the tasks required, could not practise the art to the full, if other things were allowed to get in the way.

It was close to Lugnasad and that summer’s end when my father told me his own story at last. We sat before the fire after a long day’s work, drinking our ale. At such times we were mostly silent, each absorbed with our own thoughts. I was watching Father as he stared into the flames, and I was thinking how he was losing weight, the bones of his face showing stark beneath the skin. He was even paler than usual. Teaching me must be a trial to him sometimes. No wonder he looked weary. I would have to try harder.

‘You know we are descended from a line of sorcerers, Fainne,’ he said suddenly, as if simply following a train of thought.

‘Yes, Father.’

‘And you understand what that means?’

I was puzzled that he should ask me this. ‘That we are not the same as ordinary folk, and never can be. We are set apart, neither one thing nor the other. We can exercise the craft, for what purpose we may choose. But some elements of magic are beyond us. We may touch the Otherworld, but are not truly of it. We live in this world, but we never really belong to it.’

‘Good, Fainne. You understand, in theory, very well. But it is not the same to go out into the world and discover what this means. You cannot know what pain this half-existence can bring. Tell me, do you remember your grandmother? It is a long time since she came here; ten years and more. Perhaps you have forgotten her.’

I frowned in concentration. ‘I think I can remember. She had eyes like ours, and she stared at me until my head hurt. She asked me what I’d learned, and when I told her, she laughed. I wanted her to go away.’

Father nodded grimly. ‘My mother does not choose to go abroad in the world. Not now. She keeps to the darker places; but we cannot dismiss her, nor her arts. We bear her legacy within us, you and I, whether we will or no, and it is through her that we are both less and more than ordinary folk. I had no wish to tell you more of this, but the time has come when I must. Will you listen to my story?’

‘Yes, Father,’ I whispered, shocked.

‘Very well. Know, then, that for eighteen years of my existence I grew up in the nemetons, under the protection and nurture of the wise ones. What came before that I cannot remember, for I dwelt deep in the great forest of Sevenwaters from little more than an infant. Oak and ash were my companions; I slept on wattles of rowan, the better to hear the voice of the spirit, and I wore the plain robe of the initiate. It was a childhood of discipline and order; frugal in the provision for bodily needs, but full of rich food for the mind and spirit, devoid of the baser elements of man’s existence, surrounded by the beauty of tree and stream, lake and mossy stone. I grew to love learning, Fainne. This love I have tried to impart to you, over the years of your own childhood.

‘The greater part of my training in the druid way I owed to a man called Conor, who became leader of the wise ones during my time there. He took a particular interest in my education. Conor was a hard taskmaster. He would never give a straight response to a question. Always, he would set me in the right direction, but leave me to work out the answers for myself. I learned quickly, and was eager for more. I progressed; I grew older, and was a young man. Conor did not give praise easily. But he was pleased with me, and just before I had completed my training, and might at last call myself a druid, he allowed me to accompany him to the great house of Sevenwaters to assist in the ritual of Imbolc.

‘It was the first time I had been outside the nemetons and the depths of the forest. It was the first time I had seen folk other than my brethren of the wise ones. Conor performed the ritual and lit the sacred fire, and I bore the torch for him. It was the culmination of the long years of training. After supper he allowed me to tell a tale to the assembled company. And he was proud of me: I could see it on his face, clever as he was at concealing his thoughts. There was a gladness in my heart that night, as if the hand of the goddess herself had touched my spirit and set my feet on a path I might follow joyfully for the rest of my days. From then on, I thought, I would be dedicated to the way of light.

‘Sevenwaters is a great house and a great túath. A man called Liam was the master there, Conor’s brother. And there was a sister, Sorcha, of whom wondrous things were said. She was herself a powerful storyteller and a famous healer, and her own tale was the strangest of all. Her brothers had been turned into swans by an evil enchantress, and Sorcha had won them back their human form through a deed of immense courage and sacrifice. Looking at her, it was hard to believe that it might be true, for she was such a little, fragile thing. But I knew it was true. Conor had told me; Conor who himself had taken the form of a wild creature for three long years. They are a family of considerable power and influence, and they possess skills beyond the ordinary.

‘That night everything was new to me. A great house; a feast with more food than I had ever seen before, platters of delicacies and ale flowing in abundance, lights and music and dancing. I found it – difficult. Alien. But I stood and watched. Watched a wonderful, beautiful girl dancing, whirling and laughing with her long copper-bright hair down her back, and her skin glowing gold in the flare of the torches. Later, in the great hall, it was for her I told my story. That night it was not of the goddess nor my fine ideals that I dreamed, but of Niamh, daughter of Sevenwaters, spinning and turning in her blue gown, and smiling at me as she glanced my way. This was not at all what Conor had intended in bringing me with him to the feast. But once it had begun there was no going back. I loved her; she loved me. We met in the forest, in secret. There was no doubt difficulties would be raised if we were to make our intentions known. A druid can marry if he wishes, but it is very unusual to make that choice. Besides, Conor had plans for me, and I knew he would not take the idea well. Niamh was not promised, but she said her family might take time to accept the idea of her wedded to a young man whose parentage was entirely unknown. She was, after all, the niece of Lord Liam himself. But for us there was no alternative. We could not envisage a future in which we were apart. So we met under the oaks, away from prying eyes, and while we were together the difficulties melted away. We were young. Then, it seemed as if we had all the time in the world.’

He paused to cough, and took a sip of his ale. I sensed that telling this tale was very difficult for him, and kept my silence.

‘In time we were discovered. How, it does not matter. Conor’s nephew came galloping into the nemetons and fetched his uncle away, and I heard enough to know Niamh was in trouble. When I reached Sevenwaters I was ushered into a small room and there was Conor himself, and his brother who was ruler of the túath, and Niamh’s father, the Briton. I expected to encounter some opposition. I hoped to be able to make a case for Niamh to become my wife; at least to present what credentials I had and be afforded a hearing. But this was not to be. There would be no marriage. They had no interest at all in what I had to say. That in itself seemed a fatal blow. But there was more. The reason this match was not allowed was not the one I had expected. It was not my lack of suitable breeding and resources. It was a matter of blood ties. For I was not, as I had believed, some lad of unknown parentage, adopted and nurtured by the wise ones. There had been a long lie told; a vital truth withheld. I was the offspring of a sorceress, an enemy of Sevenwaters. At the same time I was the seventh son of Lord Colum, once ruler of the túath.’

I stared at him. A chieftain’s son, of noble blood, and they had not told him; that was unfair. Lord Colum’s son; but … but that meant …

‘Yes,’ said my father, eyes grave as he studied my face, ‘I was half-brother to Conor, and to Lord Liam who now ruled there, and to Sorcha. I bore evil blood. And I was too close to Niamh. I was her mother’s half-brother. Our union was forbidden by law. So, at one blow, I lost both my beloved and my future. How could the son of a sorceress aspire to the ways of light? How could the offspring of such a one ever become a druid? It was bright vision blinded, pure hope sullied. As for Niamh, they had her future all worked out. She would marry another, some chieftain of influence who would take her conveniently far away, so they would not have to think about how close she had come to besmirching the family honour.’

There was a dark bitterness in his tone. He put his ale cup down on the hearth and twisted his hands together.

‘That’s terrible,’ I whispered. ‘Terrible and sad. Is that what happened? Did they send her away?’

‘She married, and travelled far north to Tirconnell. Her husband treated her cruelly. I knew nothing for a time, for I was gone far away in search of my past. That is another story. At last Niamh escaped. Her sister saw the truth of the situation and aided her. I was sent a message and came for her. But the damage was done, Fainne. She never really recovered from it.’

‘Father?’

‘What is it, Fainne?’ He sounded terribly tired; his voice faint and rasping.

‘Wasn’t my mother happy here in Kerry?’