Полная версия

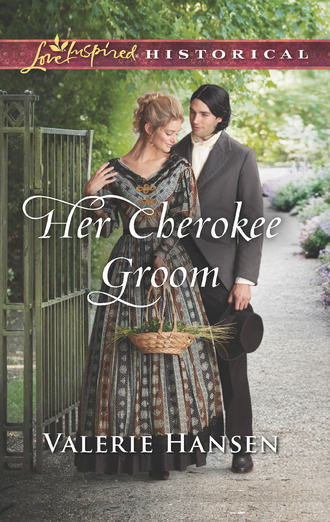

Her Cherokee Groom

“Why not?”

“Because it’s wrong. What would your uncle Charles say if you did something like that?”

“I am the son of a chief’s son. I will go.”

“Please, don’t talk like that,” she pleaded. “Think of all the trouble it would cause if you left.”

She could tell by the child’s stoic expression that he was beyond listening to the pleas of a mere girl.

There was only one thing to do. She would have to send word to Mr. McDonald to stop by again and have a stern word with the boy before he and the rest of the delegation left town. Until then she’d keep a close eye on Johnny. A very close eye.

“I think you and I should take our supper alone tonight and get to know each other,” Annabelle suggested.

“Will they not miss you?”

“No,” she admitted sadly. “The family usually insists I be present only for formal dinner parties.”

She reached down to gently smooth his hair. “I’m certain they will want to present you to their Washington friends soon. Mr. Eaton is a very important man. Being secretary of war means he works closely with President Jackson.”

The child did not look impressed. Smiling, she offered her hand. “Come. We’ll explore the house together so you won’t get lost.”

“I never get lost,” he insisted.

“Good for you.”

Grinning, Annabelle started up the spiral staircase, explaining as she went. “Down the hall at the end is the guest room. You’ll sleep there.”

Before he could ask she added, “My room is right next to that one,” and sensed him starting to relax.

Poor little thing. He acted so brave and put on such a grown-up front it was easy to forget how young he was.

No wonder he’d thought about running away. He had to be frightened nearly out of his mind.

Shivering, she realized she, too, was worried about his future. It was easy to put herself in his place because she shared it. Neither of them truly belonged in this stoic family and neither could depend on fair treatment from their so-called parents.

John Eaton had always acted preoccupied and distant toward her. His new wife, Margaret, was far worse because she paid attention to everything and could be very vindictive if displeased, which was most of the time. The older woman had had a sordid reputation in Washington before her marriage to Eaton. The more Margaret and Annabelle interacted, the more credence the rumors of perfidy gained. And the more trepidation they generated.

Margaret had already fired every young female servant in the Eaton household and had made it clear that Annabelle’s presence was barely tolerable. There was no foundation for such jealousy but it nevertheless existed. Perhaps, because Johnny was a boy, he would not encounter so much of Margaret’s malice.

Until the child got used to his new life here in Washington City, Annabelle vowed she would protect and guide him. It would be no chore to teach him city ways and household rules. Truth to tell, she was looking forward to the opportunity.

The fact that he was a smaller version of his uncle gave her heart an added prick and reminded her that she must contact Charles McDonald as soon as possible and entreat him to return and lecture the child about fidelity.

Annabelle’s stomach clenched. If Margaret even suspected that Johnny was planning to run away, the whole household would suffer her fits of foul temper, probably for weeks on end.

Chapter Two

Moonlight gleamed on the rippling surface of the Potomac, making the water shimmer like molten silver. If not for the noise of the city behind him, Charles might have imagined that he was standing on the banks of the Chattahoochee, back home, listening to a cacophony of frogs and the calls of night birds.

How much longer would Georgia be home to the Cherokee? he wondered. Some of his people had already migrated of their own volition but until the tribal elders had the solemn promise of the current president that their claim to lands farther west would be honored, he and many others were reluctant to pack up and go.

A flock of white egrets took to the sky, startled by something near the river’s edge. Charles instinctively slipped into a copse of trees.

“I seen him come this way,” someone said. “High falutin he was, too. Real fancy dressed.”

Another man chortled and spat. “Well, he can’t have gone far. We’ll get him. And then we’ll teach ’em to stay where they belong.”

“Don’t forget, I get his stickpin.”

Charles automatically reached for his pistol and grabbed empty air. The delegation had been instructed to exemplify peace. Consequently, he was unarmed.

Moving so slowly, so fluidly, that the roosting wild birds were not disturbed, he inched backward until his shoulders met the trunk of an enormous oak. Then he consciously calmed his mind and waited.

Leaves rustled. Nearby bushes shook.

The would-be assailants were nearly upon him.

* * *

Annabelle’s supper with Johnny had been uneventful except that he had eaten little. She felt so sorry for him she didn’t argue when he asked, “May I go up to my room?”

“Of course. I know you must be weary.”

“Are you coming upstairs?”

“In a few minutes,” she replied. “I have one errand to take care of first. Go ahead. I’ll be up soon.”

She watched him climb the stairs, then turned to check the empty hallway. There was pen and ink in a writing desk tucked into an alcove off the parlor. While the Eatons were dining, she could avail herself of the opportunity to write a short note to Charles—Mr. McDonald. The mere thought made her blush and hurry toward the desk. She must not be observed, nor did she dare let anyone see to whom her innocent letter was addressed. Not if she hoped to be able to carry out her plan and stop the child from fleeing.

She dipped the nib in the inkwell and began, “Dear Sir,” ending with her signature and placing his name on the outside of the folded note paper. Her penmanship was not perfect because she’d had so little chance to practice and because her hands were trembling, but it would suffice. It would have to.

Replacing everything she had moved and used, she quietly closed the slanted lid of the desk and slipped the note into her pocket.

A quick, furtive check of her surroundings confirmed that she was still alone and she quietly headed for the carriage house to seek out one of the grooms and ask him to carry her missive to Plunkett’s.

Although the sun had set, the moon was nearly full and there was plenty of reflected light from the lampposts lining the broad avenues of the capitol as she entered the rear garden. A few couples strolled arm in arm outside the iron fence while drays and coaches went about their business in the street.

Annabelle had swung a thin, gray cape around her shoulders as soon as she was outside. Now she lifted the hood, less for warmth than to hide her passage through the garden.

She patted her pocket. The sooner the note was delivered, the sooner she’d stop worrying.

In the street beyond the familiar garden path a teamster snapped his whip and shouted, “Out of my way!”

Curiosity caused her to look. Astonishment stopped her cold. Was that...? Could it be...? She’d left him only a few minutes ago, yet the young boy in the street looked terribly familiar. And with good reason.

Heart pounding, Annabelle almost called out, “Johnny!” before she thought better of it. So far, no harm had been done. If she could overtake him and get him back into the house before either of them was missed she might save everyone a lot of unnecessary grief.

She fumbled the gate latch in her nervousness, thereby slowing her progress. By the time she reached the street the boy had vanished.

Where would he go? Washington was a big city and they were both on foot. If she were Johnny, what would she do?

“Go back to the boardinghouse where the Cherokees are staying,” Annabelle guessed. She had to be right. If Johnny disappeared in a city this vast, his chances of being hurt or accosted were immense, particularly since he didn’t blend in with the dirty street urchins who were out and about at this hour.

Nervous, she glanced back at the house. Few lamps were glowing. No one would miss her. Gathering a handful of her skirt and cape she hurried in the direction where she had last spied the runaway child.

Prayer was on her lips. “Please, God, please. Help me? Guide me?”

It was then that she realized her Heavenly Father already had. She already knew that the boardinghouse the Cherokees had chosen was only a block or so past the cathedral where the family worshipped every Sunday. She knew the way.

Circumventing trouble as best she could, she darted back and forth across the broad streets, dodging coaches and buggies while evading those individuals who might wish to do her harm. She had never ventured out alone at night and the face of the city was quite different than she had expected.

The boardinghouse Annabelle sought was built in the Federalist style with tall, narrow banks of windows facing the street and a small porch that led directly into the parlor. Seeing Plunkett’s finely lettered sign gave her hope and renewed energy.

Before she’d taken two steps up the front stairs, however, Johnny burst out the door and ran past, snatching away what was left of her breath.

She lunged to grab his sleeve.

He struggled, twisting and kicking.

“Johnny! Stop. It’s me.” She pushed back her hood so he could better see her features.

“We have to go.” Johnny pointed. “This way.”

“No. I came to speak to your uncle.”

“That is why we have to go,” the boy insisted. “The man inside said he went to the river.”

“He’ll be back. We can stay here and wait.”

The child tore himself from her grasp. “No! It is not good. We must find him.”

Annabelle was unconvinced. Now that they had both made it to the boardinghouse the most sensible choice was to tarry there.

Unfortunately, Johnny was already running again.

“All right,” she called, quickly recovering. “Wait for me. I’m coming.”

They soon left the open streets for a parklike area and slowed to a walk because there was no artificial light. Patches of fog drifted in front of them as if clouds had sunk to earth, muting even the moon glow.

Johnny abruptly grasped her hand and tugged. “Stop.”

Annabelle’s breath caught. “Why? I thought you were in a hurry.”

Rethinking their possibly tenuous safety, she pushed back the hood of her satin cape once again and bent over him to speak more softly. “What’s wrong?”

“Men. Bad men. Fighting.” He pointed.

She had barely made out shadowy shapes when there was a muffled shout. The boy broke free and raced toward the altercation!

“Johnny, no!” Fisting her skirt she ran after him.

Someone yelled.

Annabelle drew closer. Her eyes widened. “Oh, no!”

A well-dressed gentleman was doing hand-to-hand battle with two ruffians and it was impossible to tell who had the upper hand. Now she understood the boy. Charles McDonald was being attacked and although he seemed to be holding his own at the moment, he was definitely outnumbered.

Charles threw a punch that sent one of the thugs reeling out of sight among some saplings, and dove after him. Bushes rustled and shook. A man grunted. Another shouted. The thug left in the open staggered and fell to his knees as if hurt or intoxicated. Perhaps both.

The seconds passed for Annabelle in slow motion. She heard another cry. Was that a splash? Were they that close to the Potomac?

The man she could see struggled to his feet and braced himself, ready for more fight. Charles reappeared and engaged him by circling, arms wide, ready for further attack. They locked arms and began grappling while Johnny beat the back of his uncle’s foe with a broken branch and screeched unintelligibly in his native language.

The men fell together. Charles scrambled up first. His foe moved more slowly yet was far heavier and thus had the advantage of sheer weight when he threw himself back into the melee.

This was a new conundrum for Annabelle. She had never seen grown men fight, so she stood aside, gaping helplessly and standing clear. Her hands were clasped in front of her so tightly they ached.

Then she saw something metal flash in the stranger’s hand and her attitude changed. “A knife! He has a knife.”

Charles crouched and stepped sideways, keeping just out of the assailant’s reach. “Stay back!”

The other man was slow and clumsy, carving harmless arcs in the night air, yet Annabelle knew it was only a matter of time until someone made a fatal misstep. What could she do? How could she possibly help the Cherokees?

Without warning, the attacker changed tactics and lunged for Johnny.

The child was too quick for him.

Charles grabbed a handful of dirt and threw it into the other man’s face. “Hey! Over here.”

The ploy worked. The burly man whirled, distracted, wiping at his eyes. But how long would that hold him off?

Annabelle had never in her life felt so powerless. So useless. As long as Charles’s adversary was the only one armed, there was no way she could be certain the Cherokee would prevail. Unless...

Whipping off her cape she twirled it at arm’s length and watched it billow out. The man with the knife was temporarily distracted and Charles darted in to try to disarm him. They wrestled until the attacker whipped one arm to the side and threw Charles to the dirt.

Annabelle could tell he was stunned when he landed. Johnny ran between his uncle and the knife-wielder, shouting and hitting him with the leafy branch.

The man roared and stood tall, facing both Cherokees. He was taller and much bulkier than she was but as long as his attention was so focused on Charles, Annabelle knew she had the element of surprise on her side.

With an unspoken prayer, she circled behind the big man, threw the cape over his head and yanked it down.

Blinded and surrounded, he flailed and slashed at the silky material, cutting portions of it to ribbons and opening gaps that were almost wide enough to let him see his opponents.

Annabelle screamed. Johnny rushed at the confused thug from one side, hitting him with a solid enough blow that he instinctively whirled to redirect his attack.

That gave Charles enough time to get to his feet, knock the other man off balance and disarm him. He threw him to the ground facedown and pinned him there. “Give up and I won’t hurt you more.”

Johnny was not so forgiving. “No! Hit him again!”

Annabelle sympathized with the child, even after the thug stopped struggling, and she had to admire Charles’s self-control. She stood back, hands clenched once more, while he and Johnny tore strips from her ruined cape to truss up the would-be robber like a Christmas goose.

“Keep a sharp lookout,” Charles warned, getting to his feet and taking a defensive stance with the other man’s knife. “There were two of them. I knocked one into the river but he could have climbed out by now.”

“If he has half a wit he’s long gone,” she said. “What in the world were you doing out here all alone?”

“I could ask you the same thing.”

“I followed Johnny,” she replied. “I’d written you a note asking you to visit and talk some sense into him before you left the city. I was on my way to the stables to ask someone to deliver it to you when I saw him running down the street. That changed everything.”

Seeing the doubt reflected in his shadowed expression she said, “Here, I’ll prove it to you.” As she slipped her hand into her skirt pocket her self-assurance turned to chagrin. “Oh, dear, I don’t know what became of my note.”

“How big was the paper?” Charles was scanning the nearby ground.

Annabelle joined him. “Small. I had folded it so it would fit in my pocket. I doubt we’ll find it without a torch.”

“Then forget it.” His brows arched. “I had thought the boy was in good company with you. Looks as though I’ll have to rethink my conclusion.”

“We had both expected to find you at the boardinghouse, sir,” Annabelle countered, spine stiff and eyes blazing from his scolding. “If you had been there, none of this would have happened.”

“Sadly, true.” He closed and pocketed the thug’s knife, then dusted off his clothing and his hands. “All right. I’ll escort you both home and then go report this fellow’s crimes.”

“But, what if he gets loose and escapes while we’re gone? What if his friend comes back and frees him?”

“That can’t be helped.” Charles slipped off his coat and shook it, then draped it over her shoulders. “You’re shivering. This will help.”

“Thank you. My cape is ruined.”

“Since you saved my life with it I will be delighted to replace it.”

“I can’t let you do that. What would people say?”

“That a gallant lady sacrificed her cape to rescue the victim of a mugging?”

“I hardly see my part as being gallant. I was merely trying to keep the fight fair.”

That made him laugh. “Have it your way. Just please allow me to buy you a new cape.”

Annabelle sighed. “I suppose that can be arranged, if you insist. The Eatons always use the same wonderful seamstress, a Miss Mills. Her shop is in Arlington, but...” Her eyes widened and she faltered, staring up at her stalwart companion. “Oh, dear. I hadn’t thought of that.”

“Of what?”

“No one knows I ventured out tonight. If Mrs. Eaton finds out from the dressmaker that I need a new cape, she will be furious with me. And perhaps with Johnny, too.”

“Then we’ll simply keep this incident to ourselves and I’ll pay Miss Mills to do the same when I engage her,” Charles promised. “Right now, I think I should see you home so you can go back inside as if nothing has happened.”

“I never lie.”

“Then you are a truly exemplary lady,” he said, sounding amused. When he looked down at Johnny, however, his countenance sobered. “You will do as you’ve been told and stay out of trouble, Tsani. This is your home now and you will honor our tribe’s promises. Understand?”

Annabelle saw the child nod and bow his head as if the weight of the world lay on his thin shoulders. Poor little thing. Truthfully, it would be just as well if she were not sent off to boarding school. Johnny needed her there.

Her thoughts whirled and danced like moths drawn to a glowing lantern. She had prayed for guidance, assuming the answer lay merely in the choice of an alternate school. Now it was beginning to look as if her answer to those prayers was a resounding no, but for a very good reason. One that certainly countered the disappointment.

Shivering as the excitement wore off and weariness lay heavy, she was thankful for many things. One was the Cherokee ambassador’s strong arm around her shoulders and his strength to lean against.

Having been warned against allowing any grown man to touch her thus, she was terribly confused. Surely those admonitions did not apply to her current situation.

Nothing that felt this right, this perfect, could possibly be wrong.

Chapter Three

“Were so many lamps burning in the house when you left?” Charles asked, pausing with his little group before escorting them back across New York Avenue.

Annabelle shook her head. “No. Mrs. Eaton usually does needlework in the evenings and Mr. Eaton sometimes reads the newspaper or personal communications from the president, but the rest of the rooms are rarely lit.”

“That’s what I was afraid of. I suspect they have missed you already.”

“Oh, no.”

“It may not be as bad as it looks. I suggest you and the boy go back inside alone, though. Being seen with me will probably not be to your advantage.”

“We did nothing wrong.”

“You and I know that. Others may be harder to convince and I’m not looking forward to being lynched on my first diplomatic mission.”

“Surely, if I tell the family you have assisted me they will understand.”

“To do that you’d have to admit to having gone out after dark. Alone. Are you sure that’s wise?”

She looked so crestfallen he had to smile. “I’ll be fine. I’m going straight to my elders to report the attack by the river. You go inside and tell the Eatons you and the boy just stepped out into the garden. That won’t be a lie.”

“All right.”

As he reclaimed his coat she tilted her face up to him and he could see moisture sparkling on her lashes. Against his better judgment he gently took her hands, noting that she was trembling. “Don’t worry. I’ll wait right here until you’re safely inside.”

“Thank you for seeing us home.”

“I should be the one thanking you for saving my neck. I’m sorry about your cape. I’ll send a messenger to the dressmaker for you first thing in the morning.”

“A cape was a small price to pay for our victory over evil.”

Let her go, his mind insisted. Step away from her and forget you ever met Annabelle Lang.

But he would not, could not, do so. Although he assumed that this goodbye would be their last, he also knew she would linger in his thoughts and in his dreams for a long, long time. Being so taken with this innocent beauty had not only been a surprise, it had left him questioning his future without her.

That notion was beyond ridiculous, of course. Even if he happened to be sent to Washington again, chances were good that Eaton would forbid them to court properly, meaning he would be fortunate to encounter her at all.

That was one way in which Cherokee courtships and marriages were better. All a couple basically had to do was share a meal and exchange blankets and they were considered wed. Many of his kinsmen partook of two ceremonies, the Christian one and the tribal one, thereby satisfying both factions.

What was he thinking! Charles asked himself, coming to his senses. He barely knew this girl.

I’m far from home and lonely, that’s all, he insisted. There’s nothing wrong with me that being back in Georgia where I belong won’t fix.

He purposefully released Annabelle’s hands and stepped away while donning his coat. To his chagrin the fabric retained her warmth and a trace of a sweet scent like roses. Just like Annabelle’s hair.

“You’d better go in,” Charles said, sounding more brusque than he’d intended.

She bowed her head demurely. “That’s wise. Good night. And God bless you, sir.”

“He did that when He sent you to my aid.”

“Perhaps because in my prayers I had asked to be of help to you and the boy. Are you a Christian, then?”

“Yes. I went to the missionary school.”

Her smile was so sweet, so tender, all Charles could do was stand there and watch her walk away. And with her went a tiny portion of his heart despite his firm decision to remain stoic.

* * *

Lucy, the heavyset, dusky-skinned cook, was in the kitchen poking the ashes of the stove to get them to ignite fresh fuel when Annabelle and Johnny entered. She wiped her hands on her apron. “Land sakes, girl. Where you been? Mr. John is tearin’ his hair.”

“I—we—stepped out into the garden to look at the stars.”

“Then why didn’t you come when he hollered for you?”

“I guess I didn’t hear.” Annabelle’s guilty conscience nagged at her to explain further. If she hadn’t had little Johnny to protect she would have confessed without delay.

“Well, get in there and let the mister know you’re all right. After the trouble tonight he’ll surely be glad to see you.”

“Trouble? Because of me?”

“Mercy, no.” The cook’s coffee-colored forehead knit above graying brows. “Somebody done made off with that fancy silver tea set the missus got from them Indians.” Her gaze darted to the boy, then quickly back to Annabelle. “He be with you all the time?”

“Yes. Of course he was.”

“If you say so. But Mr. John, he was plum mad, ’specially when he couldn’t find neither of you.”