Полная версия

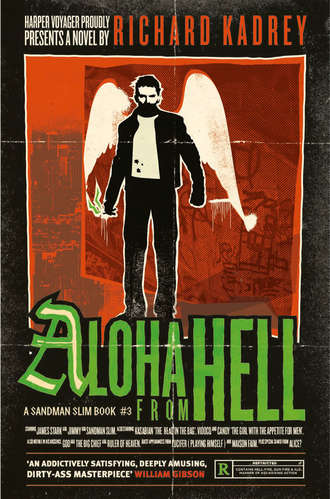

Aloha from Hell

While I talk to Dad, Vidocq examines the smoking patches some of his potions have left on the floor. They spread out in spider legs, each one a different color. I have no idea what it’s telling him, but it looks impressive.

I give Candy the last packet of salt and she lays down a line beneath the window.

K.W. gives us a half smile and shakes his head.

“Seeing you three reminds me of Tommy’s friends. They were into magic. Claimed to know about these kinds of things. Some of them called themselves Sub Rosas. It just seemed silly at the time. You know, kids dabbling in old stuff no one understands to impress their friends and bug their parents.”

His smile gets broader, like he’s found a memory that doesn’t hurt.

“You’re not quite like them, though,” he says. “You look like you might have a clue.”

“Thanks,” I say.

I wish we had a fucking clue right now. I go to where K.W. is standing. He’s still in the hall. Hasn’t so much as stuck a toe into Hunter’s room.

“Let me make sure I have this straight. Thomas, your older son, was heavy into magic with his fashion-victim friends. Did Hunter want to play Merlin, too? Even something small and silly like a Ouija board.”

K.W. shakes his head.

“Not after he saw what it did to Tommy. He was just a kid at the time, but he remembers. Hunter’s into sports, Xbox, and girls.”

“You sure? You didn’t know he was taking drugs.”

He waves a hand, palm up. A dismissal.

“That’s different. You can hide drugs. When Tommy was into that stuff, there were magical books, crystals, twigs, and potions all over his damn room. When Jen asked him to clean up, he said his friends were the same way. There’s a picture of him and a bunch of the kids. Would that help you?”

“You never know.”

He still won’t come into the room.

“You, lady,” he says to Candy. “By your left foot, there’s a photo in a frame. Would you bring it to me?”

She gets it and hands it to K.W.

He looks at the photo for a minute, not sure he wants to show it to us, an intimate thing he doesn’t want to share. Finally, he hands it to me.

“See what I’m talking about?”

There’s a group of six kids. Harry Potter by way of Road Warrior. My neck hurts and my stomach is in knots. I hand him back the shot. Take out my phone and pretend to look at the time.

“Mr. Sentenza, before we go any further, I think we should talk to Father Traven. Thanks for letting us have a look around.”

“That’s it? That’s all you’re going to do?”

“We’ll know how to proceed after consulting with the father. Don’t want to piss off any spirits by coming at them the wrong way.”

“That makes sense, I guess. So, you’ll call when you know more?”

“Exactly. Thanks.” I turn to the others. “Let’s go.”

Vidocq and Candy look at each other, but follow me out. Vidocq shakes K.W.’s hand.

“Thank you for your hospitality. Please say good-bye to your wife for us.”

I’m heading for the door, leaving the two of them to catch up with me.

“You’ll call back soon, right? Hunter is still out there somewhere.”

I turn and give him what I hope is a reassuring smile.

“We’ll call right after we confer with the father.”

I head back to the Volvo and fire it up. I already have it in gear when the others get in.

“What’s wrong with you?” asks Candy. “Why are we running out on that family?”

I don’t answer until we’re down the driveway enough that I can’t see the house anymore.

“I need to get clear of that place. I’ve got to think.”

“What’s wrong?”

Vidocq is in the front seat. He’s looking at me hard.

“Thomas, the older kid in that photo? Hunter’s big brother? He’s TJ.”

“Who’s TJ?” Candy asks.

“He was in my magic Circle with Mason. He was there the night I got dragged Downtown. I never even knew his name was Tommy. I was going to kill him with the others when I came back, only Kasabian told me he’d already killed himself.”

Vidocq nods.

“It seems more likely now that the demon who sang that ‘Mr. Sandman’ song knows you after all.”

“Doesn’t it just? But I can’t think of any demons I’ve pissed off. I kill Hellions and hell beasts.”

“People, too,” says Candy.

“They usually deserve it most.”

Vidocq says, “Perhaps at Avila. Or something you did for the Golden Vigil. Perhaps you killed or injured a possessed person, ruining the demon’s host. That might be enough for it to want revenge.”

“Then why wouldn’t the demon come after me? Or you or Candy or Allegra? Even Kasabian? Someone I give a damn about.”

“Perhaps the father can answer that question. Let’s hope so.”

I cut around cars and thousand-dollar mountain bikes cruising Studio City’s quiet, privileged streets, running the Volvo away from TJ’s Haunted Mansion ride and onto the freeway. The exhaust fumes and clogged lanes are like a welcome-home party. The knots in my stomach are getting worse. I feel cold. I hold the steering wheel tight enough I feel it bend and get close to breaking. The angel in my head moves back into the dark. It recognizes this kind of anger and knows it’s not going to talk me down. If it speaks or touches, it might burn up in the heat.

“This is what I get for going soft. For backing off. I don’t kill anything for a while and the world starts coughing up this shit. Okay. I get the message loud and clear.”

“You need to calm down if we’re going to talk to the father,” Vidocq says.

“I am calm. I don’t know what exactly is going on, but what I do know is that someone or something is daring me to find them and maybe this preacher can tell me what. I’ll do it old-school. No bullets. Just the knife and the na’at, like back in the arena.”

“You scare me when you’re like this, Jimmy.”

“Not me,” says Candy quietly from the back.

“Good, because when I get this thing figured out, I’m going to bring down all kinds of Hell on these assholes and this city.”

I’VE CALMED DOWN a little when we reach Father Traven’s place near the UCLA campus.

Vidocq’s been playing navigator, running us up and down every little side street in the county. He can read a map as well as anyone, but I think he’s been buying time, hoping that if he drags out the drive long enough, I won’t storm into Traven’s place like it’s D-Day. The plan sort of works, but mostly it’s seeing where the father lives that brings down my blood pressure.

Traven has an apartment in an old art deco complex from the thirties and the place really shows its age. It was probably beautiful once, back before reality TV, when lynching and TB were the most popular pastimes. Now the building’s best quality is that it stands as a big Fuck You to all the developers who wake up with a hard-on every morning dreaming of plowing the place under and turning the land into a business park or prefab pile of overpriced condos. If I ever find out who owns the place, I’ll buy them a case of Maledictions.

Father Traven lives on the top floor. In a normal building, that would be luxury central. The penthouse suite. In this one, it’s pretty much a sock drawer with a view. The original architect had the brilliant idea of putting storage and utility areas at both the top and bottom of the building. Maybe elevators didn’t work that well back in the thirties. Maybe he was anal-retentive. Sometime in the long history of the building, someone chopped up those top-floor spaces and tried to convert them into apartments, only they weren’t designed to be a happy place for anything except rats and mops. The ceilings are too low and are at funny angles. The untreated wooden floors are warped. You’d have to call in Paul Bunyan to chain-saw the top of the building off and rebuild it from scratch to make Traven’s bachelor pad into something anyone but a ghost or an excommunicated sky pilot would love.

We take the elevator up to the floor below Traven’s and walk up a set of bare, uncarpeted stairs. Traven’s apartment door is open a few inches when we get there. I don’t like unexpected open doors. I knock and push it open, my other hand under my coat on the .460.

Traven is sitting at a desk scribbling away on yellow paper that looks old enough to have Spanish Inquisition letterhead at the top. He stops writing and lifts his head, speaks without turning around.

“Ah. You must be God’s other rejects. Please, come in.”

Traven gets up from a long desk piled high with books. Really, it’s the kind of fold-up conference table you see in community centers. I don’t know if he’s getting ready for work or a church bake sale.

As we come in, Traven extends his hand. He gives us a faint smile, like he wants to be friendly but hasn’t had any reason to be for a long time and is trying to remember how to make his face work.

“I’m Liam Traven. Good to meet you all. Julia has told me a lot about you.”

He turns to Candy.

“Well, about two of you.”

She takes off her sunglasses and beams at him.

“I’m Candy, Mr. Stark’s bodyguard.”

Traven grins at her. He does it better this time.

“It’s very nice to meet you all.”

He steps out of the way so we can get farther into the place.

The apartment is small but neat and brighter than I expected. Whoever cut up the place installed a couple of big picture windows overlooking UCLA. There are books, scrolls, and folded sheets of vellum, mystical codices, and crumbling reference books everywhere. Even some pop-science and physics textbooks covered in highlighter marks and Post-its. Brick-and-board bookshelves line the walls and there are more books on the floor. Vidocq heads right for them and starts eyeballing the piles.

“I owned many of these years ago. Not here. I had to leave my library when I left France. I haven’t seen some of these texts in a hundred years.”

He kneels and picks up a bound manuscript from the floor. It’s so old and worn it looks like someone sewed dried leaves together and slapped a cover around them. Vidocq opens it carefully, flips through a few pages, and turns to Traven.

“Is this the old Gnostic Pistis Sophia?”

Traven nods and walks over to Vidocq.

“There it is. I’ve been looking for that. Thank you. And yes, it’s the Pistis.”

“I thought there were only four or five of these left in the world?”

Traven gently takes the book and puts it on a high shelf with other moldering titles.

“There’s more than that if you know where to look.”

I say, “Maybe there’s one less now that you’re not punching the clock for the pope. I bet that wasn’t a going-away present.”

Traven glances up at the manuscript and then to me.

“We do rash things at rash moments,” he says. “Later, we sometimes regret them. But not always.”

“God helps those who help themselves,” says Candy.

“Especially the ones who don’t get caught. Don’t worry, Father. We don’t have a problem with rash. The first thing I did when I got back to this world was roll a guy for his clothes and cash. He threw the first punch and I’d recently woken up on a pile of burning garbage, so I figured God would understand if I helped myself to some necessities.”

Father Traven is in his fifties, but his ashen complexion makes him look older. His voice is deep and exhausted, but his eyes are large and curious. His face is lined and deeply creased by years of doing something he didn’t want to do, but did anyway because he thought it needed to be done. It’s a soldier’s face, not a priest’s. There’s something else. He’s definitely not Sub Rosa—I would have known that the moment I touched his hand—but I can feel waves of hoodoo coming off him. Something weird and old. I don’t know what it is, but it’s powerful. I bet he doesn’t even know about it. Also, I think he’s dying. I smell what could be the early stages of cancer.

“The lucky among us might get the same deal as Dysmas. Dysmas was one of the thieves crucified next to Christ. When he asked for forgiveness, Christ said, ‘Today you will be with me in paradise.’”

Candy and Vidocq wander around the room. I’m still standing and so is Traven, protectively, in front of his desk. He likes seeing people, but values his privacy. I know the feeling.

“I know a dying story, too. Ever hear of a guy named Voltaire? Vidocq told me about him. I guess he’s famous. On his deathbed the priest says to him, ‘Do you renounce Satan and his ways?’”

“And Voltaire says, ‘My good man, this is no time for making enemies,’” says Traven. “It was a popular joke in the seminary.”

Framed pictures of old gods and goddesses line the walls. Egyptian. Babylonian. Hindu. Aztec. Some jellyfish-spider things I haven’t seen before. Candy likes those as much as Vidocq likes the books.

“These are the coolest,” she says.

“I’m glad you like them,” says Traven. “Some of those are images of the oldest gods in the world. We don’t even know some of their names.”

The angel in my head has been chattering ever since we got here. He wants to get out of my skull and run around. This place is Disneyland to him. I’m about to slap a gag on him when he points out something that I hadn’t noticed. I scan the walls to make sure he’s right. He is. Among all the books and ancient gods there isn’t a single crucifix. Not even prayer beads. The father lapsed a long time ago or he really holds a grudge.

“Would you like some coffee or hot chocolate? I’m afraid that’s all I have. I don’t get many guests.”

“No thank you,” says Vidocq, still poking at Traven’s bookshelves.

“I’m fine, Father,” says Candy.

He didn’t mention scotch, but I get a faint whiff of it when he talks. Not enough for a normal person to notice. Guess we all need something to take the edge off when we’re booted from the only life we’ve ever known.

“I’m not a priest anymore, so there’s no need to call me ‘Father.’ Liam works just fine.”

“Thank you, Liam,” says Candy.

“I’ll stick with ‘Father,’” I say. “I heard every time you call an excommunicated priest ‘Father,’ an angel gets hemorrhoids.

“What is it you do exactly?” I ask.

He clasps his hands in thought.

“To put it simply, I translate old texts. Some known. Some unknown. Depending on who you ask, I’m a paleographer, a historical linguist, or paleolinguist. Not all of those are nice terms.”

“You read old books.”

“Not ordinary books. Some of these texts haven’t been read in more than a thousand years. They’re written in languages that no longer exist. Sometimes in languages that no one even recognizes. Those are my specialty.”

He looks at me happily. Is that the sin of pride showing?

“How the hell do you work on something like that?”

“I have a gift for languages.”

Traven catches me looking at the book on his desk, pretends to put a pen back into its holder, and closes the book, trying to make the move look casual. There’s a symbol carved into its front cover and rust-red stains like blood splattered across it. Traven takes another book and covers the splattered one.

I sit down in a straight-back wooden chair against the wall. It’s the most uncomfortable thing I ever sat in. Now I know what Jesus felt like. I’m suffering mortification of my ass right now. Traven sits in his desk chair and clasps his big hands together.

He tries not to stare as the three of us invade his inner sanctum. His heartbeat jumps. He’s wondering what he’s gotten himself into. But we’re here now and he doesn’t have the Church or anywhere else to run to anymore. He lets the feeling pass and his heart slows.

“Before, you said, ‘When I got back to this world.’ You really are him, then? The man who went to Hell and came back? The one who could have saved Satan’s life when he came here?”

“God paid your salary. Lucifer paid mine. Call it brand loyalty.”

“You’re a nephilim. I didn’t know there were any of you left.”

“That’s number one on God’s top-forty Abomination list. And as far as I know, I’m the only one there is.”

“That must be very lonely.”

“It’s not like it’s Roy Orbison lonely. More like people didn’t come to my birthday party and now I’m stuck with all this chips and dip.”

Traven looks at Vidocq.

“If he’s the nephilim, you must be the alchemist.”

“C’est moi.”

“Is it true you’re two hundred years old?”

“You make me sound so old. I’m only a bit over one hundred and fifty.”

“I don’t think I’d want to live that long.”

“That means you’re a sane man.”

Traven nods at Candy.

“I haven’t heard about you, young lady.”

She looks at him and smiles brightly.

“I’m a monster. But not as much as I used to be.”

“Ignore her,” I tell him. “She’s just showing off and hardly ever eats people anymore.”

Traven looks at me, not sure if I’m kidding.

“If you’re in the exorcism business, you must know a lot about demons.”

“Qliphoth,” he says.

“What?”

“It’s the proper word for what you call a demon. A demon is a bogeyman, an irrational entity representing fear in the collective unconscious. The Qliphoth are the castoffs of a greater entity. The old gods. They’re dumb and their lack of intelligence makes them pure evil.”

“Okay, Daniel Webster. What happened at the exorcism?”

Traven takes a breath and stares at his hands for a minute.

“You should know that I don’t follow the Church’s standard exorcism rites. For instance, I seldom speak Latin. If Qliphoth really are lost fragments of the Angra Om Ya, the older dark gods, they’re part of creatures millions of years old. Why would Latin have any effect on them?”

“How, then, do you perform your exorcisms?” asks Vidocq.

“My family line is very old. For generations we served communities the Church hadn’t reached or wouldn’t come to. I use what I learned from my father. Something much older than the Church and much more direct. Best of all, God doesn’t have to be involved. I’m a sin eater, from a long line of sin eaters.”

Candy comes over.

“I don’t know what that is, but can I be one, too?”

I give her a look.

“How does it work?”

“It’s a simple ritual. The body of the deceased is laid out naked on a table in the evening, usually around vespers. I place bread and salt on the deceased. I lay my hands on the body. The head. The hands. The feet. I recite the prayers my father taught me, eating the bread and salt.

“With each piece, I take in the body’s sins, cleansing the deceased until the soul is clean. When my father died, I ate his sins. When his father died, he ate his sins, and so on and so on, back centuries. I contain all of the accumulated sins of a hundred towns, hamlets, armies, governments, and churches. Who knows how many? Millions I’m sure.”

I take a pack of Maledictions from my pocket and offer one to Traven.

“Do you smoke, Father?”

“Yes. Another of my sins.”

“Light up and we’ll ride the coal cart together.”

I light two with Mason’s lighter and hand one to the father.

Traven takes a puff, coughs a little. Maledictions can be a little harsh if you’re not used to them. Really, they taste like an oil-well fire in a field of fresh fertilizer. Traven sees the pack in my hand and his eyes widen a fraction of an inch.

“Are those what I think they are?”

“The number one brand in Pandemonium.”

He holds the Malediction out and looks at it.

“It’s harsh, but not as awful as I thought it would be.”

“That’s Hell in a nutshell,” I say. “Tell me about Hunter.”

“It seemed to be going well. You see, a Qliphoth can only possess an imperfect and impure body, one that’s sinned. Of course, that describes all humans except maybe for the saints. When I eat a possessed person’s sins, their body returns to a pure and holy state. With nowhere left to hide, the Qliphoth is ejected like someone spitting out a watermelon seed.”

“Where did it go wrong?”

“I’d laid out the bread and salt and I was saying the prayers. Not in Latin, but in an older language supposedly spoken by the Qliphoth and possibly the Angra Om Ya.”

Traven opens his mouth and what comes out is all humming, gurgling, and spluttering, like he’s drowning and speaking Hellion at the same time.

“I felt the Qliphoth being drawn out as I swallowed Hunter’s sins. It knew what was happening and fought back hard. No doubt you’ve seen the wreckage. Toward the end of the ritual, the Qliphoth tried to drag the boy’s body into the air. I shoved bread and salt into Hunter’s mouth, hoping it would draw out the creature. I prayed and ate the bread. That should have worked. It’s always worked before, but something went wrong. Imagine that I was erecting a castle to push the Qliphoth out and keep it out. Something went wrong and it burst through the walls and back into Hunter’s body. That’s the last thing I remember before Julia helping me to my feet. By then, Hunter was gone out the window.”

“Did you recognize the demon?” I ask.

“No. It’s none I’ve ever encountered before. It wasn’t angry or frightened until it realized that I knew how to force it out. That’s unusual for Qliphoth. They’re incomplete creatures and they know it, so it makes them fearful and vicious. This one was patient and thoughtful.”

Traven walks to the windows and opens them to let the smoke out. I follow him so I can flick my ashes outside over the university.

I say, “I think we’re going to need more information before we try the exorcism again. We’re missing something important.”

“I’ve been going through my books trying to identify the specific creature, but I haven’t had any luck.”

“Perhaps I can help you with your research,” says Vidocq. “I have my own library, if you would like to see it.”

“Thank you. I would.”

“You two can play librarians. I’m going to make some calls and break some people’s toys until one of them starts giving us answers.”

“Cool,” Candy says.

“Father, I know you must use the university library. Have you ever heard anyone talk about a drug called Akira?”

“Of course. It’s popular among some of the students. Artists. New Agers. Those sort of thing.”

“Do you know anything about the drug itself?”

“Not really. All I remember is that it seemed like it was harder to get than other drugs. That there were only a few people who sold it.”

“Thanks.”

I shake Traven’s hand and I let Vidocq and Candy go out ahead of me. I start out, stop, and turn. It’s an old trick.

“One more thing, Father. Julia never told us why you are excommunicated.”

He’s thinking. Not sure he wants to answer.

“I’ll tell you if you promise to talk with me about Hell sometime,” he says.

“Deal.”

Traven goes back to his desk and picks up the book he’d hidden earlier.

“I don’t like other people to see this particular book. It seems wrong for it to be a mere curiosity.”

“I saw you cover it up.”

The spray of red on the front of the book nearly covers an ancient sigil.

“I don’t recognize the symbol.”

“It’s the sign of one of the Angra Om Ya cults,” says Vidocq, looking over my shoulder.

Traven nods.

“You’ll understand why the church was so angry with me. They have an unswerving policy that there is no God but their God. There never was and there never will be. But there are some who believe that there’s more to Creation than what’s in the Bible and that the stories in this book are at least as convincing as those.”

“You translated the Angra Om Ya’s bible. No wonder God doesn’t want you whacking his piñata anymore.”

“Certainly the Church doesn’t.”

“It isn’t all bad, Father. I own a video store. Come around sometime. The damned get a discount.”

He gives us one of his exhausted smiles.

“That’s very kind of you. Since leaving the Church, I’ve come to believe that it’s the little, fleeting pleasures like watching videos that mean the most in this life.”