Полная версия

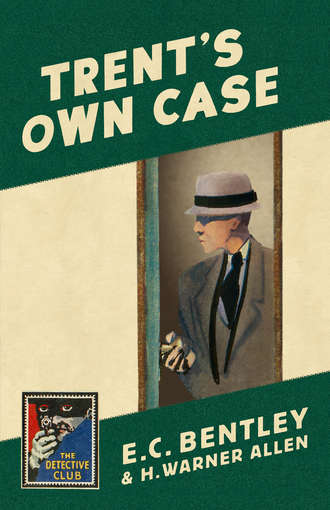

Trent’s Own Case

Verney arose and crossed his arms. ‘I mean this,’ he said harshly. ‘Randolph made no bequests at all. He left no will.’

CHAPTER VI

AN ARREST HAS BEEN MADE

THERE was a momentary silence as Trent took in this amazing statement and its implications.

‘The man who murdered Randolph,’ Verney said, ‘has probably killed half a dozen invaluable charities and other good works stone dead with that same bullet. Besides that, he has dried up completely a great stream of benevolence that spread itself out in all directions. For I am convinced that there is no will; and if there is no will, what is to happen to the Randolph fortune, and to the causes that it supported, heaven alone knows. Somebody will inherit, I suppose; but there will be delay, and who can answer for what he will do with the money? He may prefer horse-racing, or yachting, or play-producing, or any other way of getting rid of money by the cartload. One thing is practically certain; he won’t live on a few thousands a year, and devote the rest to well-directed benevolence.

‘Another thing,’ Verney went on, holding up an expository finger. ‘There may be rival claimants, and a dispute dragging on indefinitely; for as far as I know Randolph had no near relations. You may have heard that he had a son, an only son, who disappeared from home when he was about sixteen, and has never been heard of since. The old man did everything possible to find out what had happened to him, but no trace of him was ever found and he was given up for dead long ago. But there may be other relatives. You see what a disaster the whole thing is likely to be, apart from the personal loss of such a man, and such an influence for good.

‘There is one detail,’ Verney went on after a moment’s pause, ‘of interest to you. Randolph was very anxious that you should paint a replica of the Tabarders’ portrait of him, to be hung in the hall of the Institute. Did you hear about that?’

‘I had a note from him about it,’ Trent said, ‘but nothing was settled.’

‘Well, it never will be now,’ Verney said; and then broke out desperately: ‘I tell you, Trent, the shock and the horror of this business, and the prospect of so much wreckage, have driven me pretty nearly insane.’ And Verney sunk his head between his hands, his fingers clutching his hair.

Trent, while his lips took a dubious twist, put a hand on the young man’s shoulder. ‘Better not meet trouble half-way,’ he said. ‘After all, the whole thing depends on your belief that Randolph had made no will. What grounds are there for thinking that he could have been guilty of such an amazing piece of imprudence as that? It’s really hardly credible.’

Verney, without looking up, shrugged his shoulders. ‘The grounds for thinking so are good enough, unfortunately. The fact is that, at the time of his death, he was really thinking, for the first time, about putting his affairs in order. His lawyers had been dropping hints for a long time that it was high time he made a will. I told him so myself, too, more than once—it was my obvious duty to do so, I thought, though a very unpleasant one. Whenever I did, he made it quite clear that there was no will as yet. He used to say there was time enough, that he was good for many years yet. But he hated the subject being mentioned—didn’t like the idea of dying, I suppose, like many other people; though if any living being had a right to feel confident about his prospects in the next world, Randolph had. And then at last he did begin to consider the thing seriously. Several times he said things that showed me he was thinking about the disposal of his estate. And then, before he had got to the point of doing anything definite, he was struck down.’

Trent thought for a few moments before saying: ‘Still, he may have made a will earlier in life—when he was married, for instance. Men usually do, I believe.’

Verney made a gesture of impatience. ‘He may—yes; when he was a comparatively poor man with no great philanthropic interests to think about. But if he did, I think he would have mentioned it; and anyhow, it’s not to be supposed that the terms of any such will would prevent everything getting into the sort of hopeless mess that I’m thinking about. Then, apart from his own foundations, there are all the causes that had expectations as regards Randolph’s estate—had a right to have them, I mean, seeing that for years he had been a regular and generous supporter of them.’

‘What sort of things do you mean?’ Trent asked. ‘Never having been a philanthropic millionaire, it would interest me to know how it all works—if you won’t think I’m being irreverent to say so.’

Verney looked into vacancy, as one assembling his ideas. ‘Why,’ he said, ‘to put it the simplest way, there must have been dozens of secretaries and chairmen of committees trying, at odd times, to sound me discreetly about what Randolph’s testamentary dispositions were. There’s the Humberstone General Infirmary; and the Humberstone Endowed Schools Foundation; and the Moss Lane Congregational Church of the same place; and the London Missionary Society; and the British and Foreign Bible Society; and the Yorkshire Congregational Union; and the Congregational Pastors Retiring Fund; and Leeds University; and the Scalbridge United Independent College; and the National Lifeboat Institution; and the Harrowby Seamen’s Institute; and the Dewsby Deaf and Dumb Institute; and—oh! I could name another dozen or more that have a direct interest in what happens to Randolph’s estate.’

‘Thanks! Thanks!’ Trent said smiling. ‘You needn’t go on, Verney, I see how it is. I’d no idea your field of work was such an extensive one. It’s no business of mine, of course, but I’m afraid this is going to be a serious thing for you personally.’

Again Verney shrugged. ‘It will send me hunting another job, after over two years of such a job as I shall never get again. But I’m not worrying about that just now. I want,’ he said savagely, ‘to see the man who killed Randolph taken and hanged—the cowardly brute who shot a defenceless old man in the back, and cut short a life that was given up to works of mercy and humanity. I suppose they’ll run the fellow down, Trent—you understand these things. It’s not likely he’ll escape, do you suppose?’

‘No, not likely,’ Trent said. ‘It does happen of course, now and then. But you have to give the police a reasonable allowance of time when a murder has been undiscovered for a good many hours, as I gather from what you tell me.’

Verney nodded. ‘Yes, naturally. I suppose it must depend on the traces left behind by the murderer—the weapon, footprints, fingerprints, the kind of thing one reads about.’

‘If he was careful,’ Trent pointed out, ‘he need not have left any traces at all. Criminals often don’t; but they may easily get found out all the same. Do you remember exactly what it was that was given out to the papers this morning?’

‘I’ve got one here.’ Verney produced a folded copy of the Sun from his coat pocket. ‘There you are—it’s little enough.’

Below an array of headlines, and a portrait of a clean-shaven, hard-looking old man, Trent read as follows:

At an early hour this morning the police were called to No. 5, Newbury Place, Mayfair, the London residence of Mr James Randolph, the millionaire whose long record of charitable activities and public beneficence has made his name honoured throughout the country.

He had been shot through the heart, the body lying on the floor of the bedroom, where he had, it is presumed, been dressing before attending the banquet of the Tabarders’ Company.

His absence from the banquet caused surprise, as he was a member of the Court of the Company, and was to have spoken to the toast of the guest of honour on this occasion, the Home Secretary. On inquiry at Tabarders’ Hall this morning, we learn that several attempts were made during the evening to call Mr Randolph’s house by telephone, but that the calls were unanswered.

Mr Randolph’s valet, the only servant sleeping on the premises, was, in fact, out for the evening; and it was by him that the body was discovered on his returning to the house, when he immediately telephoned the police.

No. 5 Newbury Place is one of a row of mews converted into five small residences, all tenanted by persons of social position. Such a house was well adapted to the simple way of life preferred by the late Mr Randolph, for he spent but little time in London, and lived as a rule at Brinton Lodge, his country house in the neighbourhood of Humberstone, Yorks.

‘So that’s all,’ Trent remarked. ‘Most of that was written up in the Sun office, after they’d made their own inquiries. There’s hardly anything at all about the crime itself, is there?’

‘Hardly anything,’ Verney agreed. ‘But I suppose it’s all that was given out. The other evening papers have just the same; not a syllable more. I’ve looked carefully.’

Trent considered the other’s haggard face for a moment in silence. ‘Well, the officer who saw you this morning,’ he suggested, ‘didn’t he tell you anything more? By the way, it’s the kind of case they would put Bligh onto, I should think, if his hands aren’t too full already. Was your visitor a tall, powerful-looking sort of bloke with a head like a billiard-ball?’

‘That was his name,’ Verney said with a faint smile, ‘and your description fits him nicely. No, he hadn’t a word more to tell me than there is in that paper. It was I who was expected to do the telling—whether I knew of anyone who could conceivably have had any ill-will against Randolph, or whether he had seemed at all upset or unusual in his manner lately, or whether I knew what he kept in the safe in the bedroom; and so on. And to all of that my answer was no, and no, and no. The inspector also wanted to know how I had been spending my own time that evening.’

Trent laughed. ‘Of course,’ he said. ‘That’s the routine.’

‘So he was good enough to assure me,’ Verney said, with an answering gleam of grim amusement. ‘Fortunately I was able to satisfy him that my time had been fully occupied, in the presence of other people. It was the Institute Athletic Club’s weekly grind that evening, you see. I never miss running with the boys, and after changing, I stayed on with them in Kilburn, till half past ten, as I usually do. And now I must be off. It’s been a relief to talk the thing over.’

Trent rang the bell. ‘You might wait and see the latest edition,’ he said. ‘It’s usually delivered here before this time.’

Mrs McOmish appeared at the door, a copy of the Sun in her outstretched hand. ‘If it’s the paper you want—’ she said.

But her speech was cut short by an exclamation from Trent, who had already caught sight of the line of capitals strung along the top of the first page. He seized the paper from her and read aloud to Verney the brief paragraph which had been added, in heavy type, to the matter which he had already seen dealing with the Newbury Place murder.

‘It is understood,’ he read, ‘that an arrest has already been made in connection with this abominable crime.’

CHAPTER VII

ON A PLATE WITH PARSLEY ROUND IT

VERNEY had taken his leave, and Trent had noted that he was properly impressed—not to say astounded—by the fact, if fact it were, of the swift success of the official hunt for Randolph’s murderer. Trent had busied himself at once in procuring copies of all the latest editions and comparing their statements; then, after a meditative dinner, he had rung up a certain number in Bloomsbury, and proposed himself for a private and friendly call upon Chief Inspector Bligh, whom he was lucky enough to find at the other end of the wire.

The number of Trent’s friends among the metropolitan police, in its various grades, was small, but his relation with them was entirely one of mutual liking; and there was none with whom he was on easier terms than Mr Bligh, an officer of unusual parts, whose range of interests went considerably beyond his notable equipment of expert professional knowledge. In particular, he had made a hobby, and owned a considerable library, of the history of the Civil War in the United States.

It was nine o’clock when Trent found the inspector deeply engaged with book and pipe in his comfortable bachelor quarters.

‘Sorry to spoil your evening,’ Trent said as he placed his hat on a chair.

‘You won’t,’ Mr Bligh assured him. ‘If I’d thought you were likely to, I’d have told them downstairs to set the dog on you, instead of bringing up the drinks for you. Help yourself.’ And he waved a vast hand towards the tray with its convivial contents on the plush-covered table.

Trent took the armchair facing his host’s, and began the filling of a pipe. ‘Oh blessings on his kindly face and on his absent hair!’ he said. ‘I’ve interrupted your reading, anyhow. What is the book, I wonder? But need I ask? It is the Life, Campaigns, Letters, Opinions and Table-talk of General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, the Victor of Pumpkin Creek.’

‘There’s no such book,’ Mr Bligh retorted positively; ‘and,’ he added after a moment’s thought, ‘there wasn’t any such battle. What I was reading was Bernard Shaw—my favourite author.’

‘Another bond between us!’ Trent exclaimed. ‘And what draws you so especially to Shaw?’

The inspector patted affectionately the volume lying on his knee. ‘Shaw,’ he declared, ‘is the literature of escape. That isn’t,’ he added, in answer to Trent’s bewildered gaze, ‘my own expression.’

‘You relieve my feelings,’ Trent gasped, ‘more than I can say.’

‘No,’ the inspector said reminiscently. ‘That was the phrase used about Shaw by the man who first brought him to my notice. I had to interrogate a prisoner some years ago about a certain matter. A confirmed criminal, he was. They used to call him Pantomime Joe, on account of the cheek he used to give everybody from the dock. Why, if I’ve heard a judge say once that his court wasn’t a music hall, when Joe was on his trial, I’ve heard it half a dozen times. Joe was an educated man, and it was no surprise to me, when I visited him in his cell, to find him reading a book from the prison library. He showed it to me—Plays Pleasant, by G. B. Shaw. “What’s this?” I said. He grinned at me. “This is the literature of escape, Blighter,” he says, using a silly nickname he and his sort have always had for me. I thought that sounded a funny sort of reading to be put in the hands of a man who spent half his time in gaol, but he explained his meaning.’

‘And what can that have been?’ Trent wondered.

‘Why,’ the inspector said, ‘Joe meant, and I agree with him, that Shaw takes you right out of the beastly realities of life. I can tell you, after a hard day at our job, with all the spite, and greed, and cruelty, and filthy-mindedness that we get our noses rubbed in, it’s like coming out into the fresh country air to sit down to one of Shaw’s plays. Nobody half-witted, nobody brutal, nobody to make you sick. And if he ever does try to give you anybody who is a rotten bad lot, he doesn’t come within miles of the real thing. And there’s never a dull moment. Every dam’ character has something to say; even the stupidest ones. Everybody scores off everybody else. Who ever had the luck to listen to anything like it in real life? I tell you, it’s a different world.’

Trent nodded his appreciation of this. ‘But,’ he said, after a brief silence, ‘it was the world we live in that I wanted to consult you about.’

‘The Randolph murder,’ Mr Bligh said. ‘I know; you said so on the phone. And you have been painting his portrait, staying at Brinton to do it. And last week the man who runs the Randolph Institute said it would be a good idea to have a replica of it to hang up there. And Randolph was persuaded to agree, and wrote asking you to call at Newbury Place yesterday evening at six, which you did. And then he talked to you about doing the replica. And then you left, about six fifteen—so that you were one of the last persons to see the old man alive. Well! You’ve got something to tell me that I don’t know, I hope.’

Trent gazed at him as if in awe. ‘I don’t think,’ he said humbly, ‘there can be anything you don’t know. You have forgotten for the moment, perhaps, that he and I had a little disagreement, and I declined to do the job. Apart from that, I have nothing to add to your summary of the proceedings. How do you do it, Inspector? I may have an open countenance, but I hardly think you can have read all that in my face. Were you up the chimney listening to us, or what?’

Mr Bligh smiled grimly. ‘Information received—that’s what we usually call it,’ he said. ‘As for listening, Simon Raught, Randolph’s man, does all of that that’s required when he’s on the premises. Most of what I’ve mentioned he happened to hear, quite accidentally, last week at Brinton; and as for your visit, of course, he told me all about that.’

‘Of course,’ Trent agreed. ‘Be told, sweet Bligh, and let who will be clever; hear useful things, not deduce them, all day long. All the same, you will not persuade me that all that perfectly good information fell into your lap, as it were, when you were not noticing. I have seen Simon Raught only a few times—in fact, he never got as far as telling me his Christian name, as he evidently did with you—but he did not strike me as one who, when in trouble, would insist that all his secrets should be sung even into thine own soft-conchéd ear. I won’t inquire how you got all that out of him—there are various ways and means, I know. The thing I really wanted to ask you when I came here appears not to be in any doubt. The case is in your hands, as I hoped it might be.’

‘Good guess,’ the inspector remarked sardonically.

‘And you ask if I have anything to tell you—about Randolph as he was at our interview, I suppose you mean? No, I haven’t. He said nothing about anyone coming to see him after I had gone. He didn’t say anything about expecting to be shot, and he didn’t look as if he was. He seemed just as usual, in excellent health, and perfectly satisfied with himself.’

‘Hm! That doesn’t help much,’ Mr Bligh said. ‘Well, why did you want to see me about the case, then? We all understood you had gone out of the amateur sleuthing business long ago.’

‘Just because I happened to know Randolph, and to know some things about him that interested me—things I had heard before I made his acquaintance through painting his portrait, and things I have learnt since. And only this afternoon I was told a good deal by his secretary, Verney, whom I had met at Randolph’s house last January. He had already been giving you information, I gathered, earlier in the day.’

The inspector nodded. ‘But not a lot that I didn’t know. There was that about his having left no will, of course, which seems to be the case. But bless you! That’s not an unheard-of thing, even with the general run of wealthy people; and old James Randolph was not exactly an ordinary character.’

‘That’s just it. I know how very far from ordinary he was, and that’s why I’m interested. Besides, one of the reasons why I went out of business, as you call it, was that my wife has a morbid distaste for crime; but just now she is in the Cotswolds. I am alone and free, like the man in Chesterton; shameless, anarchic, infinite.’

‘I don’t know about anarchic and infinite,’ Mr Bligh said pointedly. ‘Well,’ he added, assuming an expression of regretful sympathy, ‘I’m more sorry than I can say, but there’s no need to let the thing trouble your ingenious brain any further, my lad. We’ve got the man.’

‘The papers have been told so—I saw that. And that is why I came to you; to hear more.’

‘The papers have been told nothing of the sort,’ Mr Bligh said testily. ‘They’ve found out for themselves that an arrest has been made, and they may possibly have found out that the man arrested was connected with one of Randolph’s concerns, and had just been sacked. But they’ve said nothing about its being the man who shot Randolph, because of course they daren’t; and in fact he hasn’t been charged with that. All the same, he’s the man.’

‘He is, is he?’ Trent looked into the other’s rugged face. ‘Swift work, with a vengeance. You’re certain about having got the man? Is the case really, so to speak, in the bag already?’

Mr Bligh’s smile was grim. ‘In closest confidence, as usual, I don’t mind telling you that I have clear evidence of the man’s having been in Randolph’s house in the evening, when Randolph was there alone. I have also—’

‘Yes,’ Trent murmured. ‘An “also” would seem to be in order.’

‘Also,’ the inspector went on, after blowing a couple of elaborate smoke-rings, ‘I have the man’s written and signed confession that he murdered Randolph.’

Trent fell back in his chair, while Mr Bligh resumed his pipe and gazed dreamily at a corner of the ceiling.

‘That seems to have made you think a bit,’ he remarked after a moment, cannily observant of a slight frown on his guest’s usually untroubled countenance. ‘I shouldn’t wonder if you had been working up some valuable theory of your own about the case. If you have, let’s hear it. A good laugh’s the best tonic in the world. Come on! Am I right?’

‘Very often, I dare say,’ Trent said, with a swift return to his accustomed manner. ‘Not now. I never had the slightest notion of a theory about the case. I only heard of it three hours ago. But I do take an interest in it as I told you, and I thought, with my well-known helpfulness, that you might like to have a talk about it, and even let me have a look at the scene of the crime; but now, perhaps, everything being as you tell me, you’d rather not.’

Mr Bligh rubbed his chin. ‘I don’t know about that,’ he said slowly. Then, after a few moments’ consideration, he added: ‘It’s like this. The evidence is all there. I’ve told you, roughly, what it is. But there are some queer things about the case all the same, and we might as well have a yarn about it.’

‘Just what I should like. You know it’s safe to talk to me.’

‘If it wasn’t, my lad, you wouldn’t be here.’ A chuckle agitated the crumpled expanse of Mr Bligh’s waistcoat. ‘Well, you’ve seen what little there is in the papers, of course.’

‘Certainly; and it’s very little indeed. Can you tell me one thing, for instance, that they don’t mention—just how Randolph was shot?’

‘He was shot through the heart from behind, probably from the direction of the door of the bedroom, when he was just taking his coat off. It looks as if it was done by someone who had come to see him by appointment, and whom he had let in himself, the valet being out for the evening. The bullet was fired from a Webley .455, probably fitted with a silencer.’

‘Ah!’ Trent received this information with a thoughtful brow. ‘So that’s how it was. And you’re telling me that nobody knows this as yet but the police—and the surgeon, of course.’

‘Well, the man who murdered him knows it, I suppose,’ the inspector observed.

‘Yes, I’m capable of supposing that myself,’ Trent rejoined. ‘And now that we have arrived at that point, who did murder him?’

‘We haven’t arrived at that point.’ Mr Bligh, it was clear, was taking an innocent pleasure in saving up the climax of his tale. ‘Let’s take things in their order. First, there were the obvious possibilities to be thought of.’

‘The servants, you mean.’

‘You’ve read in the paper that there was only one, a manservant, sleeping in the place. He was out for the evening, and found the body when he came home; then informed the police by phone immediately. So he said.’

Trent nodded. ‘Raught—yes, I know him. And you put him through it, of course.’

‘I thought,’ the inspector said dubiously, ‘I had wrung him pretty dry; but one couldn’t be certain. Still, he’d got a reasonable enough story about having left the place just after you left it, to spend his evening off with some relations; and he hadn’t any motive that lay on the surface. He declared that when he found the body, he was in too much of a dither even to make out how Randolph had been killed. It might be true; but naturally I didn’t set him aside. The only other servant is a charlady, Mrs Barley, who kept the place in order when Randolph wasn’t staying there. I saw her too this morning—a simple soul, she is. I thought to myself, I miss my guess if she knows anything whatever about the crime—or about anything else worth mentioning. Then, as you know, I saw Verney, the secretary, who was always about the place when Randolph was in London; and he gave me a satisfactory account of his movements on the evening of the murder.’