Полная версия

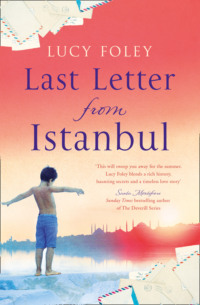

Last Letter from Istanbul: Escape with this epic holiday read of secrets and forbidden love

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Lost and Found Books Ltd 2018

Jacket design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket photographs © Stefka Pavlova/Arcangel Images (boy); Shutterstock.com (letters and landscape).

Lucy Foley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008169077

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008169091

Version: 2018-06-20

Dedication

To Al, always my first reader.

I love you.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Victorious Allies in Constantinople!

Part One

Nur

The Traveller

The Boy

Nur

George

The Boy

The Prisoner

The Traveller

Nur

The Boy

Nur

George

Nur

The Prisoner

George

Nur

The Prisoner

The Boy

Nur

George

The Boy

The Prisoner

The Traveller

The Boy

Nur

George

The Boy

Nur

Part Two

The Prisoner

Nur

George

The Traveller

The Boy

Nur

George

The Prisoner

Nur

George

Nur

The Prisoner

Nur

Nur

The Prisoner

The Traveller

Nur

George

Nur

George

Nur

The Prisoner

George

Nur

George

The Traveller

Nur

George

Snow

The Boy

The Prisoner

Nur

The Traveller

Nur

Spring

Nur

George

The Prisoner

Nur

George

The Boy

Nur

Acts of Destabilisation

George

The Prisoner

George

The Prisoner

George

Nur

George

Nur

Nur

Together

George

Then

Nur

George

The Prisoner

The Traveller

Nur

The Traveller

A Note on Names

Acknowledgements

Discover More from Lucy Foley

About the Author

Also by Lucy Foley

About the Publisher

VICTORIOUS ALLIES IN CONSTANTINOPLE!

Today, November 13, 1918, the Occupation of Constantinople began. The vanquished Ottoman Empire, which ill-advisedly threw its lot in with the German campaign, must now yield to a victorious Allied force.

British ships entered the famed Golden Horn, having travelled through the Dardanelles on Tuesday – passing right by the fateful beaches of the infamous battle of Gallipoli three years ago. A disaster for Allied forces, perhaps, but also for the then victorious Ottoman army. It was upon these same beaches that it spent the flower of its youth, a loss from which it would never recover.

Reaching the famous Golden Horn, forces numbering nearly 3,000 British, some 500 French, and 500 Italian soldiers landed immediately and occupied military barracks, hotels, houses, Italian and French schools, and hospitals. There these men will remain until the Allied administrative machine can be set up and the requisitioning of private homes begins, and order can be restored to this war-beleaguered city. These men will not return to their families like the vast majority of their soldierly compatriots. Instead they will remain thousands of miles from home in execution of this noble endeavour.

THE ENEMY ENTERS STAMBOUL

Today, November 13, 1918, enemy ships arrived in our great city, flower of our Empire. This move by the so-called Allies is in express contradiction to promises that they would not seek an occupation of Ottoman lands. Fortunately the Ottoman people have long ago learned to doubt the word of our Western European counterparts.

Men, women and children observed the advancing ships from the banks of our beloved Golden Horn, sorrow in their hearts. Some of those men had fought a valiant battle in 1915 against the ‘Allies’ on the shores of Gallipoli, losing many comrades in the process but emerging from the conflagration with victory and great honour. To see their vanquished enemy follow them here, ready to lay claim to their city and requisition their homes if the fancy should take them, is the greatest imaginable indignity.

CONSTANTINOPLE

1921

THREE YEARS OF ALLIED OCCUPATION

Nur

Early morning. In a room above the dockyards of the Bosphorus, a woman sleeps. Her hair, a long black skein of it, has tangled itself about her in the rough seas of the night. She forgot to tie it back as she usually does. Too tired. Above her head an arm is flung in a bodily abandon never shown by day. Her fingers splay, her palm open as though in supplication.

Quiet, save for the self-important ticking of a clock: a dark wood, rather brutish affair. MADE IN ENGLAND. It is conspicuous, perhaps, because there is so little furniture in the room beside it and the low divan with its sleeping human cargo. There was furniture: one can still see the darker impressions upon the floor which the sunlight has not yet been able to fade. Of rugs, too, far finer than the rather workaday affair that remains. Kilim from Anatolia, soumak from Persia.

The sun is coming. It crests over the sward of green on the opposite bank of the Bosphorus, and smooths itself across the water like so much spread butter. Now it touches Europe. In the space of a few minutes it has spanned two continents; a daily miracle. It gilds the ugly mechanical detritus of the docks. It reaches the room with its sleeper. In the fetid air another small miracle occurs: the suspended layer of dust becomes a dancing mass of fine gold particles.

No matter how frequently this apartment is cleaned, the dust remains. It may be to do with the age of the building, or the fact that it is entirely made from wood that over the years has weathered days of rain, broiling heat, frost and snow. Has shrunk and grown and warped and breathed, active as the living thing it once was.

Now the light has slunk up onto the bedclothes, finds sleeping toes beneath a funnel of material. A pattern of embroidered pomegranate, inexpertly but vividly done. The colours are almost a match for the real fruits that will ripen on the trees in a garden across the water. The red seeds of the split fruits become a pattern, marching along the border of the quilt; gold thread forms the fibrous strands between them.

Now the light reaches the tangled strands of hair. In the shade they appeared black – now they reveal themselves as various shades of brown, caught in places as bright as that gold thread. The light gathers itself for the final occupation: advancing up the neck, the fine bones of the jaw, the slightly open mouth, the prow of the nose, the eyelids …

Nur wakes. Pink light. She opens her eyes. White. She sits up, groggy, wipes her mouth. A restless night’s sleep. What woke her, in the small hours? A bad dream. She cannot recall the details now. The more she grasps at them the faster they sink, like creatures burrowing into sand. She is left only with the feeling of it, a lingering unease. More unsettling, this not-knowing. She rises, looks at the day. Across the flat rooftops she can just make out the water, a coruscation of light. She will shake this feeling from her by breakfast, she is certain. For what can there be to upset one on a morning like this?

Oh. A pause. Something is missing. Now it happens to her, as it does every morning. The remembering of all that has changed. She feels the knowledge resettle itself upon her shoulders – familiar, almost reassuringly so. For at least now she has found it again, knows the weight of it. It is far worse than the invention of any mere bad dream.

In the next room, someone is making coffee. The scent of it is like the day itself; intimations of warmth and comfort. She can hear the particular musical note of the copper pot as it strikes the stove. She thrusts her feet into her worn babouches, shuffles out into the corridor. Leaning up, chin just clearing the top of the stove where the pot exhales a dangerous plume of steam, is a small figure. The boy. He looks up at her, caught between pride and guilt. Then he smiles.

She cannot quite bring herself to be angry with him. The boy is like a different child from that of two years ago. Often, in that time, she would find him in the mornings lying upon his back with his eyes open, and wonder if they had ever closed, or if he had merely spent the night watching a projection of horrors upon the ceiling. He began to eat, at least. But there was something mechanical in it, the way he took the food and chewed, and swallowed, and opened his mouth for the next bite. It was a keeping alive, the pure instinct of an organism.

For a long while there had been no glimmer of the boy he had been. She wondered if that child had sunk completely from view – never to return. There were things that could change a person absolutely. And in childhood one was more malleable, more impressionable; the change might be all the more devastating.

She takes her cup up onto the flat roof of the building. This is her secret place; she does not think any of the other inhabitants of the apartment block know of it. Here the day cannot touch her yet. She is mistress of it. The morning is clear, still cool. But there is the promise of heat. The water is eloquent. There is a shimmer of warmth on the horizon, too, the clouds massing above are saffron-coloured.

She takes a sip of coffee. He has made it well, far better than her grandmother, who thinks herself above the making of coffee and always burns it.

The day is still as a painting. It is hard to imagine that down there is movement, chaos. But she can hear it: the waking sounds of the streets, the call of the milk seller, the faraway shouts of stevedores on the quay, the fishermen beginning to hawk the catch of the day. From a short distance away the rattle and whine of a tram. From the nearby district of Pera, some two hundred yards to the west, there comes the thin wail of a violin – relic of a night’s revelries.

Before, she never considered this area, Tophane, as somewhere one might live. It was a nowhere – an afterthought, clinging to the coattails of the great city, a place where the different neighbourhoods inevitably met up with one another, their great streets coming together like so many loose ends of string.

She looks beyond the quays, to the great sweep of the Bosphorus, spotted with warships. From up here they seem miniature, as though she might sweep them back out to sea with the flat of her hand. Below are represented three of the four languages she has in her possession. A dimly imagined peacetime future of tranquil pursuits – of Paris, London, Rome; the reading of European Literature.

The beginning of the occupation. The storm of their boots against the cobblestones. A hundred eyes observing from behind shutters in what might seem to the uninitiated like an empty street: old women, young women, hating them, fearing them. The gun turrets of the huge ugly ships in the Golden Horn swivelling toward the city’s ancient glories – the Aya Sofia, Süleymaniye, Sultanahmet. A threat unspoken, yet deafening.

Those first nights like a held breath.

And they said there would not be an occupation. They had promised it. The British, the French, the Italians – at the Armistice that ended the Great War. Even those who have never read a newspaper, even those who cannot read at all, know this. Know, now, not to trust them in anything.

The new indignities, stinging like a slap: men ordered to remove the red fezzes they had worn for as long as they could remember. Women leered at, somehow all the more so if they were wearing the veil.

Up here, on the roof, this was where she had sat, hidden from view, as soldiers of the British army marched through the streets below. Snatches of speech floated up:

‘Living like animals …’

and

‘Their women little better than whores, really …’

and

‘A man here can take as many wives as he likes …’

and

‘You might be in luck, Clarkson, if the ladies don’t have a say in it …’

and

‘Just look at the state of this place. No wonder they lost.’

Would they have been so loud, if they had known that they were being listened to and understood? She suspected – and this was the most insulting probability – that they would not have cared. The city was theirs for the taking. They even have their own name for it: Constantinople. This other name is from the realm of officialdom, of mapmakers. İstanbul: that is what people call it. That is how she has always known it, that is the place in which she grew up, familiar, beloved. But the rules are made by others now.

As those men had continued with their insults she had crawled to the edge of the rooftop, making sure to stay hidden from view. She had tilted the cup of coffee she held in her hand, and allowed a few hot drops to fall. The whim of a moment; but they fell as though she had planned her target perfectly. A fat lieutenant, removing his cap for a few seconds to scratch his bald pate. The almost perceptible sizzle as the scalding liquid made contact with the sensitive skin. His howl shrill as one of the street cats.

But those were more courageous days. Murmurings of resistance. Brave words, rebel words: they would undermine them at every turn; they would set fire to their storehouses, they would defy the curfew, they would spit in their faces. But then the indignity became commonplace. A numbness, setting in. The business of living got in the way, that was it. By silent agreement, all seemed to decide that the best form of resistance was not with outward mutiny but to continue as though absolutely nothing had happened. They would defy their enemy by ignoring the presence of khaki in the streets, the armada in the Golden Horn. With the exception of a few, that is, who work in the shadows plotting real destruction and death for the invaders.

Now she looks beyond the Bosphorus, to the opposite shore, to the dark green hillside of another continent. Asia. The few dwellings visible amidst the trees are as intricate and delicate as paper cut-outs. Among them is a white house, more beautiful than all the rest.

She is filled with longing. Familiar, but condensed this morning, as strong as she has ever felt it. Something occurs to her. Why not, she thinks? What possible harm can come of it?

She calls down to the boy, ‘I have to drop some embroideries off with Kemal Bey.’

‘I could come with you?’

‘No.’ She has a second destination in mind for the morning, now, and she must go there alone.

‘But I love it at the bazaar.’

‘Yes, I know you do. But you’re like a cat following a scent there. Last time you wandered as far as the Spice Market before I realised you had disappeared.’ The memory of that moment brings with it a reverberation of the panic she had felt. She shrugs it away. He is here, he is safe, she will not let it happen again. ‘Besides,’ she says, ‘you have some reading to do, I think?’

He casts a longing look through the window at the sunlit streets. ‘It’s so warm outside.’

‘You can read outside, then, in the sun.’

He opens his mouth, meets her gaze, closes it. She is many different things to him now. But at such times, first and foremost, she is his schoolteacher.

GARE D’AUSTERLITZ, PARIS

Almost a lifetime later

The Traveller

Early morning. November. Cold so that the breath steams, blue-cold like a veil drawn over everything. This is one of the first trains out of the station. The place is thronged with people despite the hour. There is already a small queue for newspapers and cigarettes at the tabac kiosk. The platform is already crowded. Good, I like watching people. Above me soar ribs of iron, the vaulted skeleton of some industrial age monster. A lofty, echoing space: temple to speed and efficiency.

There was another station, like this. A long while ago.

There are businessmen in uniform grey, bound for Lausanne, perhaps. At a glance they all appear mould-made, hatted and shod from the same outfitters. Many are reading papers. The latest news: nuclear tests, Russian spy rings, anti-Vietnam demonstrations. All of it the story of the now. I wonder what use they make of me, an oldish man with an even older suitcase. Or what they would make of the pages I hold, so many decades out of date. The two articles, the British and Turkish, are clipped together. I have read them many times; certain phrases are known by rote. Noble endeavour. Greatest imaginable indignity. Somewhere between them, these few terse paragraphs, is the beginning of the story. The key by which a whole life might be understood.

Funny how similar they are, these clippings: though I am sure their writers would have been appalled to know it. Two halves of a whole? The face and its reflection in the mirror – every detail reversed but essentially the same. Or the two poles of a magnet: fated to forever repel.

Us — Them.

East — West.

Somewhere in the middle: me.

Now I watch an elegant couple a few feet away. He is a few years older than she. She wears a powder pink coat, a pale shock against the grey of the businessmen and the day itself. He is in dark blue, as though his outfit is intended to provide a foil to hers, to allow it to take centre stage. They might be newlyweds, I think, off for a honeymoon in the mountains. Or they might be having a liaison; running away. There is something about the way they look at each other that suggests the latter. Snatched and hungry. A memory comes. Not crisp and whole, sharp-focused, to be replayed in the mind like a scene from a film, but consisting mainly of sensation, atmosphere.

I must be staring: the man glances straight at me, and I am caught out. I have seen something that was not meant for me – not meant for anyone other than two co-conspirators.

I prop my suitcase on the bench beside me: the leather worn into paleness at the corners.

I open it, to return the newspaper clippings to their place within. As I do I block the contents from the view of the crowd with my body; a protective instinct. Some of the baggage within, you see, is rather unorthodox. Inside my suitcase alongside my toothbrush, my change of clothes, my shaving accoutrements, I carry fragments of the past. If one of my fellow passengers has caught a glimpse of the contents they might think I am an odd sort of travelling salesman, specialising in antique curios. They might wonder exactly who I would think might have any interest in buying such items. They have no value in and of themselves. Their value as relics, as evidence, however, is infinite. They are clues as to how a brief interlude in the past shaped an entire future. So it seemed only right that I should bring them with me, these talismans, upon this journey.

The train is pulling into the station now. There is the inevitable panicked surge, as if my fellow passengers fear there won’t be space for them, though they hold tickets stamped with seat numbers. I find I am momentarily transfixed. For the first time, I realise what it is that I am doing. I have always been this way, I suppose: acting immediately, considering – regretting – at leisure. But suddenly, now, I am fearful. If I get on that train I sense that my life will change again in a way I cannot anticipate.

A reframing of the story, the same one that was broken off so many years ago, never permitted its proper conclusion. I am suddenly unsure.

The platform around me is emptying. A horn sounds, ominously. I have perhaps thirty seconds.

A hiss of releasing brakes. And then I am hurtling myself toward the train, case rattling behind, before the gaping passengers.

In through the door that the conductor is just pulling closed, into the warm car.

CONSTANTINOPLE

1921

The Boy

From the window he watches Nur hanım leave, rounding the end of the alleyway onto the larger thoroughfare with its thronging crowd. Funny, she always seems to him such a powerful person. But now he sees that compared to other adults she is not large at all. In fact she is dwarfed by many of them, and by the great bag of embroideries at her hip that causes her to stagger slightly beneath its weight. In some complicated way this worries him. He watches her now as though his gaze were a cloak that might keep her from harm, until she is lost to sight.

He knows exactly what he will do now, and it does not involve reading his schoolbooks.

He is hungry all the time. When the war came the city forgot how to feed the people that lived in it. Once food was everywhere. A different smell around every street corner: the sweet yeast of simits, piled high and studded with seeds, the brine of stuffed mussels cooked on a brazier, of fried mackerel stuffed into rolls of bread, the aroma of burned sugar drifting from the open door of a pastane, even the savoury, insubordinate tang of boiled sheep’s heads.