Полная версия

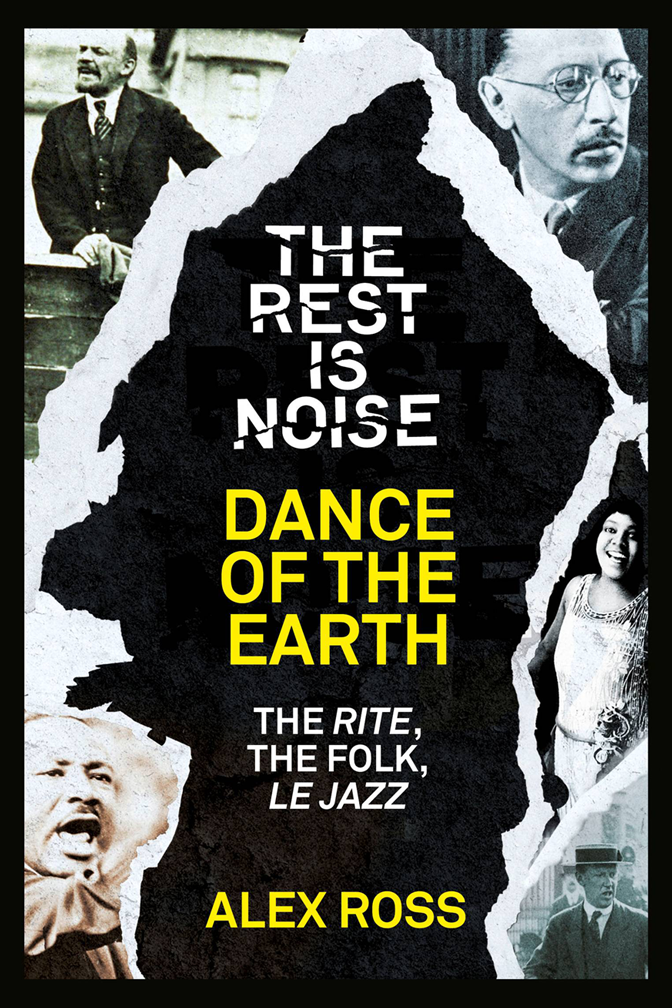

The Rest Is Noise Series: Dance of the Earth: The Rite, the Folk, le Jazz

This is a chapter from Alex Ross's groundbreaking history of 20th century classical music, The Rest is Noise.

It is released as a special stand-alone ebook to celebrate a year-long festival at the Southbank Centre, inspired by the book. The festival consists of a series of themed concerts. Read this chapter if you're attending concerts in the episode Paris: shock, glamour and experiments.

Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker, is the recipient of numerous awards for his work, including an Arts and Letters Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Belmont Prize in Germany and a MacArthur Fellowship. The Rest is Noise was his first book and garnered huge critical acclaim and a number of awards, including the Guardian First Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is also the author of Listen to This.

DANCE OF THE EARTH

The Rite, the Folk, le Jazz

From The Rest Is Noise by Alex Ross

Contents

Dance of the Earth

Notes

Suggested Listening and Reading

Copyright

About the Publisher

3 DANCE OF THE EARTH

The Rite, the Folk, le Jazz

May 29, 1913, was an unusually hot day for Paris in the spring: the temperature reached eighty-five degrees. By late afternoon a crowd had gathered in front of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, on the avenue Montaigne, where Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes was holding its spring gala. “There, for the expert eye, were all the makings of a scandal,” recalled Jean Cocteau, then twenty-three. “A fashionable audience in décolletage, outfitted in pearls, egret headdresses, plumes of ostrich; and, side by side with the tails and feathers, the jackets, head-bands, and showy rags of that race of aesthetes who randomly acclaim the new in order to express their hatred of the loges ... a thousand nuances of snobbery, super-snobbery, counter-snobbery ...” The better-heeled part of the crowd had grown wary of Diaghilev’s methods. Disquieting rumors were circulating about the new musical work on the program—The Rite of Spring, by the young Russian composer Igor Stravinsky—and also about the matching choreography by Nijinsky. The theater, then brand-new, caused a scandal of its own. With its steel-concrete exterior and amphitheater-like seating plan, it was deemed too severe, too Germanic. One commentator compared it to a zeppelin moored in the middle of the street.

Diaghilev, in a press release, promised “a new thrill that will doubtless inspire heated discussion.” He did not lie. The program began innocuously, with a revival of the Ballets Russes’ Chopin fantasy Les Sylphides. After a pause, the theater darkened again, and high, falsetto-like bassoon notes floated out of the orchestra. Strands of melody intertwined like vegetation bursting out of the earth—“a sacred terror in the noonday sun,” Stravinsky called it, in a description that had been published that morning. The audience listened to the opening section of the Rite in relative silence, although the increasing density and dissonance of the music caused mutterings, titters, whistles, and shouts. Then, at the beginning of the second section, a dance for adolescents titled “The Augurs of Spring,” a quadruple shock arrived, in the form of harmony, rhythm, image, and movement. At the outset of the section, the strings and horns play a crunching discord, consisting of an F-flat-major triad and an E-flat dominant seventh superimposed. They are one semitone apart (F-flat being the same as E-natural), and they clash at every node. A steady pulse propels the chord, but accents land every which way, on and off the beat:

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

one two three four five six seven eight

Even Diaghilev quivered a little when he first heard the music. “Will it last a very long time this way?” he asked. Stravinsky replied, “Till the end, my dear.” The chord repeats some two hundred times. Meanwhile, Nijinsky’s choreography discarded classical gestures in favor of near-anarchy. As the ballet historian Lynn Garafola recounts, “The dancers trembled, shook, shivered, stamped; jumped crudely and ferociously, circled the stage in wild khorovods.” Behind the dancers were pagan landscapes painted by Nicholas Roerich—hills and trees of weirdly bright color, shapes from a dream.

Howls of discontent went up from the boxes, where the wealthiest onlookers sat. Immediately, the aesthetes in the balconies and the standing room howled back. There were overtones of class warfare in the proceedings. The combative composer Florent Schmitt was heard to yell either “Shut up, bitches of the seizième!” or “Down with the whores of the seizième!”—a provocation of the grandes dames of the sixteenth arrondissement. The literary hostess Jeanne Mühlfeld, not to be outmaneuvered, exploded into contemptuous laughter. Little more of the score was heard after that. “One literally could not, throughout the whole performance, hear the sound of music,” Gertrude Stein recalled, no doubt overstating for effect. “Our attention was constantly distracted by a man in the box next to us flourishing his cane, and finally in a violent altercation with an enthusiast in the box next to him, his cane came down and smashed the opera hat the other had just put on in defiance. It was all incredibly fierce.”

The scene superficially resembled Schoenberg’s “scandal concert,” which shook up Vienna in March of the same year. But the bedlam on the avenue Montaigne was a typical Parisian affair, of a kind that took place once or twice a year; Nijinsky’s orgasmic Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” had caused similar trouble the previous season. Soon enough, Parisian listeners realized that the language of the Rite was not so unfamiliar; it teemed with plainspoken folk-song melodies, common chords in sparring layers, syncopations of irresistible potency. In a matter of days, confusion turned into pleasure, boos into bravos. Even at the first performance, Stravinsky, Nijinsky, and the dancers had to bow four or five times for the benefit of the applauding faction. Subsequent performances were packed, and at each one the opposition dwindled. At the second, there was noise only during the latter part of the ballet; at the third, “vigorous applause” and little protest. At a concert performance of the Rite one year later, “unprecedented exaltation” and a “fever of adoration” swept over the crowd, and admirers mobbed Stravinsky in the street afterward, in a riot of delight.

The Rite, whose first part ends with a stampede for full orchestra titled “Dance of the Earth,” prophesied a new type of popular art— lowdown yet sophisticated, smartly savage, style and muscle intertwined.

It epitomized the “second avant-garde” in classical composition, the post-Debussy strain that sought to drag the art out of Faustian “novel spheres” and into the physical world. For much of the nineteenth century, music had been a theater of the mind; now composers would create a music of the body. Melodies would follow the patterns of speech; rhythms would match the energy of dance; musical forms would be more concise and clear; sonorities would have the hardness of life as it is really lived.

A phalanx of European composers—Stravinsky in Russia, Béla Bartók in Hungary, Leoš Janáček in what would become the Czech Republic, Maurice Ravel in France, and Manuel de Falla in Spain, to name some of the principals—devoted themselves to folk song and other musical remnants of a pre-urban life, trying to cast off the refinements of the city dweller. “Our slender bodies cannot hide in clothing,” goes the text of Bartók’s Cantata profana, a fable of savage boys who turn into stags. “We must drink our fill not from your silver goblets but from cool mountain springs.”

Above all, composers from the Romance and Slavonic nations— France, Spain, Italy, Russia, and the countries of Eastern Europe— strained to cast off the German influence. For a hundred years or more, masters from Austria and Germany had been marching music into remote regions of harmony and form. Their progress ran parallel to Germany’s gestation as a nation-state and its rise as a world power. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 sounded the alarm among other European nations that the new German empire intended to be more than a major player on the international stage— that it had designs of supremacy. So Debussy and Satie began to seek a way out of the hulking fortresses of Beethovenian symphonism and Wagnerian opera.

But the real break came with the First World War. Even before it was over, Satie and various young Parisians renounced fin-de-siècle solemnity and appropriated music-hall tunes, ragtime, and jazz; they also partook of the noisemaking spirit of Dada, which had enlivened Zurich during the war. Their earthiness was urban, not rural— frivolity with a militant edge. Later, in the twenties, Paris-centered composers, Stravinsky included, turned toward pre-Romantic forms;

the past served as another kind of folklore. Whether the model was Transylvanian folk melody, hot jazz, or the arias of Pergolesi, Teutonism was the common enemy. Music became war carried on by other means.

In Search of the Real: Janáček, Bartók, Ravel

Van Gogh, in his garden at Arles, was haunted by the idea that the conventions of painting prevented him from seizing the reality before him. He had tried abstraction, he wrote to Émile Bernard, but had run up against a wall. Now he was fighting to put the brute facts of nature on canvas, to get the olive trees right, the colors of the soil and the sky. “The great thing,” he declared, “is to gather new vigor in reality, without any preconceived plan or Parisian prejudice.” This was the essence of naturalism in late-nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century art. It surfaced in works as various as Monet’s transcendent visions of train stations and bales of hay, Cézanne’s hyper-vivid still lifes, and Gauguin’s steamy visions of Tahiti. It animated various other contemporaneous cultural phenomena, such as Zola’s novels of miners and prostitutes, Maxim Gorky’s exacting portraits of peasant life, and Isadora Duncan’s free, anti formal dancing. In whatever medium, artists worked to dispel artifice and convey the materiality of things.

What would it mean for music to render life “just as it is,” in van Gogh’s phrase? Composers had been pondering that question for centuries, and, at various times and in different ways, they had infused their work with the rhythms of everyday life. The Enlightenment philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder had proposed that composers find inspiration in Volkslieder, or folk songs—a phrase he coined. Countless nineteenth-century composers installed folkish themes in symphonic and operatic forms. But they tended to take their tunes from published collections, thereby filtering them through the conventions of musical notation—major and minor scales, regular bar lines, strict rhythm, and the rest. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, scholars in the nascent field of ethnomusicology began to apply more meticulous, quasi-scientific methods, and came to the realization that Western notation was inadequate to the task. Debussy, browsing through the multicultural sounds that were on display at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889, had noticed how the music fell between the cracks of the Western notational system.

The advent of the recording cylinder meant that researchers no longer needed to rely on paper to preserve the songs. They could make recorded copies of the music and study it until they understood how it worked. The machine changed how people listened to folk music; it made them aware of deep cultural differences. Of course, the machine was itself helping to erase those differences, by spreading American-style pop music as a global lingua franca.

Percy Grainger, the Australian-born maverick pianist-composer, was among the first to apply the phonograph’s lessons. In the summer of 1906, Grainger ventured out into small towns in the English countryside with an Edison Bell cylinder, charming the locals with his rugged, unorthodox personality. Back home, he played his recordings over and over, slowing down the playback to catch the details. He paid attention to the notes between the notes—the bending of pitch, the coarsening of timbre, the speeding up and slowing down of pulse. He then tried to replicate that freedom in his compositions. In 1908 he heard a Devon sailor sing the sea shanty “Shallow Brown,” and later fashioned from it a symphonic song for soprano, chorus, and a unique chamber orchestra that included guitars, ukuleles, and mandolins. The ensemble creates a fantastic simulacrum of the sea, as pungent as any paragraph in Melville’s Moby-Dick. String tremolos churn like surf, high woodwinds squawk like gulls, lower instruments hint at terrible creatures in the depths. The voice sails above, bursting outside bar lines to drive the emotion home: “Shallow Brown, you’re going to leave me ...” With each performance, John Perring, the man whom Grainger originally recorded with his cylinder, sings his song again, and the orchestra preserves the grain of the voice as a machine could never do.

The best way to absorb a culture is to be from it. Three great “realists” in early-twentieth-century music—Janáček, Bartók, and Ravel—were born in villages or outlying towns in their respective homelands: Hukvaldy in Moravia, Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary, and Ciboure in the French Basque country. Although they were trained in the cities, and remained city dwellers for most of their lives, these composers never shook the feeling that they had come from somewhere else.

Janáček’s father served as kantor—schoolmaster and music master— of the remote hamlet of Hukvaldy. As Mirka Zemanová writes in her Janáček biography, he was hardly better off than the peasants he taught; the family lived in one room of the damp, rundown school house. At the age of eleven, Leoš received a scholarship to attend choir school in Brno, and his parents welcomed the award because they could not afford to feed all their children. He went on to study in Prague, Leipzig, and Vienna, compensating for his humble origins with a fierce work ethic. In the 1880s he founded the Brno organ school, which later became the Brno Conservatory, and began to enjoy local success as a composer in a Romantic-nationalist vein.

Then, on a trip home in 1885, Janáček experienced the street music of his village with fresh ears. In a later essay he recalled: “Flashing movements, the faces sticky with sweat; screams, whooping, the fury of fiddlers’ music: it was like a picture glued on to a limpid grey background.” Like van Gogh, he would paint the peasants as they were, not in their Sunday best.

When Janáček began collecting Czech, Moravian, and Slovakian folk songs, he wasn’t listening for raw material that could be “ennobled” in classical forms. Instead, he wanted to ennoble himself. Melody, he decided, should fit the pitches and rhythms of ordinary speech, sometimes literally. Janáček did research in cafés and other public places, transcribing on music paper the conversations he heard around him. For example, when a student says “Dobry večer,” or “Good evening,” to his professor, he employs a falling pattern, a high note followed by three at a lower pitch. When the same student utters the same greeting to a pretty servant girl, the last note is slightly higher than the others, implying coy familiarity. Such minute differences, Janáček thought, could engender a new operatic naturalism; they could show an “entire being in a photographic instant.”

The oldest of the chief innovators of early-twentieth-century music, Janáček was almost fifty when he finished his first masterpiece, the opera Jenůfa, in 1903. Like Pelléas and Salome, written in the same period, Jenůfa, is a direct setting of a prose text. The melodies not only imitate the rise and fall of conversational speech but also illustrate the characteristics of each personality in the drama. For example, there is a marked musical distinction between Jenůfa, a village girl of pure and somewhat foolish innocence who has a baby out of wedlock with the local rake, and the Kostelnička (sextoness), her devout stepmother, who eventually murders the baby in an effort to preserve the family reputation. In the opening scene of Act II, the Kostelnička sings in abrupt, acerbic phrases, sometimes leaping over large intervals and sometimes jabbing away at a single note. Jenůfa’s melodies, by contrast, follow more easygoing, ingratiating contours. Behind the individual characterizations are pinwheeling patterns that mimic the turning of the local mill wheel, the meticulous operation of social codes, or the grinding of fate. The harmonies often have a disconcerting brightness, all flashing treble and rumbling bass. The coexistence of expressive freedom and notated rigidity in the playing suggests rural life in all its complexity.

Jenůfa seems destined to end in tragedy. The heroine’s baby is found beneath the ice of the local river; the villagers advance on her with vengeful intent. Then the Kostelnička confesses that she did the deed, and they redirect their rage. Jenůfa is left alone with her cousin Laca, who has loved her silently while she has pursued the good-for-nothing Števa. Time stops for a luxurious instant: the orchestra wallows in elemental C major. Then, over pulsing, heavy-breathing chords, violins and soprano begin to sing a new melody in the vicinity of B-flat—a sustained note followed by a quickly shaking figure, which moves like a bird in flight, gliding, beating its wings, dipping down, and soaring again. This is Jenůfa’s loving resignation as she gives Laca permission to walk away from the ugliness surrounding her. Another theme surfaces, this one coursing down the octave. It is Laca answering: “I would bear far more than that for you. What does the world matter, when we have each other?” The two sing each other’s melodies in turn, the melodies merge, and the opera ends in a tonal sunburst.

Janáček, like Mahler, talked about listening to the chords of nature. While working on his cantata Amarus, he wrote: “Innumerable notes ring in my ears, in every octave; they have voices like small, faint telegraph bells.” These natural sounds are linked to the opera’s tough-natured emotional world, the hard-won love of a man and a woman in the wake of a terrible crime. No wonder audiences in Vienna and other European capitals were struck by Jenůfa when it finally made its way past Czech borders in the year 1918. Following the devastation of war, Janáček had unleashed the shock of hope.

Bartók’s father, like Janáček’s, was a teacher who worked with the rural population, running an agricultural school that aimed to introduce modern farming methods to the Hungarian countryside. He died young, and Bartók’s mother supported the family by giving piano lessons in towns around Hungary. A shy and sickly child, Béla took refuge in music even before he could speak. By the age of four, apparently, he could play forty folk songs with one finger at the piano.

In 1899, at the age of eighteen, Bartók moved to Budapest to study at the Royal Academy of Music. He made his mark first as a pianist of fierce technique and fine expression; his early compositions emulated Liszt, Brahms, and Strauss, whose Ein Heldenleben he transcribed for the piano. But his musical priorities shifted when he read the stories of Maxim Gorky, in which peasants, long scorned or prettified in literature, become flesh-and-blood people. With another gifted young Hungarian composer, Zoltán Kodály, Bartók set about inventing a new brand of folk-based musical realism.

At first, the young Hungarians followed the established formula, collecting folk melodies and concocting handsome accompaniments for them, as if putting them in display cases. Then, after several expeditions into the countryside, Bartók acknowledged the gap between what urban listeners considered folkish—a professional Gypsy band playing a csárdás dance, for example—and what peasants were actually singing and playing. He decided that he had to get as far as possible from what he would later call the “destructive urban influence.”

In his manipulation of folk material, Bartók went rather further than Janáček, who found authenticity in city and country settings alike. There was a certain fanaticism inherent in Bartók’s philosophy; as the scholar Julie Brown observes, his diagnosis of the contaminating influence of cosmopolitan culture was only a step or two away from the noxious racial theorizing that was à la mode in Bayreuth. What saved Bartók from bigotry was his refusal to locate his musical truths in any one place; he heard them equally in Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, Turkey, and North Africa. The mark of authenticity was not racial but economic; he paid heed mainly to the people on the social margins, those who had lived the toughest lives.

Bartók’s most intense encounter with the Folk took place in 1907, when he went to the Eastern Carpathian Mountains, in Transylvania, to gather songs from Hungarian-speaking Székely villagers. Personal upheaval added urgency to the mission; the composer had fallen in love with a nineteen-year-old violinist named Stefi Geyer, who received his advances first with bemusement and then with alarm. Both the letters he wrote to Geyer that summer and his meticulous notes on Transylvanian songs give the impression that a fenced-off soul is opening itself to the chaos of the outer world.

Like Grainger in England, Bartók brought with him an Edison cylinder, and he listened as the machine listened. He observed the flexible tempo of sung phrases, how they would accelerate in ornamental passages and taper off at the end. He saw how phrases were seldom symmetrical in shape, how a beat or two might be added or subtracted. He savored “bent” notes—shadings above or below the given note—and “wrong” notes that added flavor and bite. He understood how decorative figures could evolve into fresh themes, how common rhythms tied disparate themes together, how songs moved in circles instead of going from point A to point B. Yet he also realized that folk musicians could play in absolutely strict tempo when the occasion demanded it. He came to understand rural music as a kind of archaic avant-garde, through which he could defy all banality and convention.

Emotional rejection can have a radicalizing effect, as Schoenberg’s history in 1907 and 1908 suggests. Bartók, pining for the unavailable Stefi, swung away from Romantic tonality in those same two years. The Violin Concerto No. 1, his main work of this period, shows him still in thrall to a Richard Strauss aesthetic, with a five-note theme representing his beloved at the head of the piece. He planned but did not compose a third movement, which would have shown the “hateful” side of the unfortunate girl. Some of that negative energy spills out in the Fourteen Bagatelles for piano, written in the spring of 1908. A kind of substitution of love objects occurs: in place of Stefi’s leitmotif there are now rusty shards of folk melody, showing the impact of the Transylvanian trip and other research expeditions. The Woman becomes the Folk.

The first Bagatelle begins with a radical harmonic break: the right hand plays roughly in C-sharp minor while the left plays in something like the key of C (in the Phrygian mode). This is “polytonality” or “polymodality,” the juxtaposition of two or more key-areas, and it will play a significant role in early-and mid-twentieth-century music. Bartók probably derived the practice from Strauss and Debussy, but he also liked to attribute it to folk players, who periodically wandered free from their accompanying harmonies.

The Bagatelles, together with subsequent works such as the Two Elegies, Allegro barbaro, the First String Quartet, and the opera Bluebeard’s Castle, veer close to atonality. They make frequent use of Schoenberg’s searing motto chord of two fourths separated by a tri-tone. But Bartók’s ardor for folk melodies prevented him from going over the brink. As the musicologist Judit Frigyesi observes, Hungarian modernists were not prone to annihilating rage of the Viennese type; instead, they sought higher unities, transcendent reconciliations. The philosopher and critic Georg Lukács put it this way: “The essence of art is form: it is to defeat oppositions, to conquer opposing forces, to create coherence from every centrifugal force, from all things that have been deeply and eternally alien to one another before and outside this form. The creation of form is the last judgment over things, a last judgment that redeems all that could be redeemed, that enforces salvation on all things with divine force.” Bartók, likewise, talked about the “highest emotions,” a “great reality.” The artist in his loneliness need not bring about Vienna-style antagonism and scandal; instead, Frigyesi writes, he can stand in for all humanity, becoming a “metaphor for wholeness.”