Полная версия

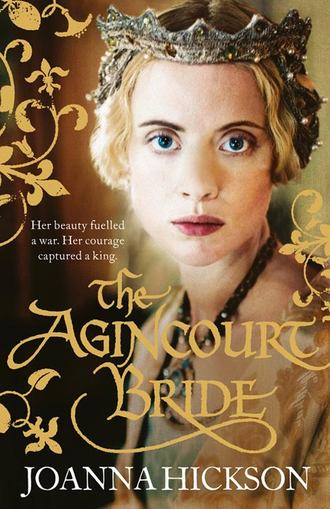

The Agincourt Bride

However, the present argument was not about who sat on what throne. This high-powered English embassy was apparently only interested in settling the dispute over territories, and in sealing the deal by acquiring a French wife for King Henry V of England, who was the great-grandson of Edward III. Well, you didn’t have to be a genius to conclude that the return to court of our king’s youngest and only unmarried daughter might have something to do with this. I decided there and then that if my darling Catherine was coming back to St Pol to be dangled before the King of England as a prospective bride, then she was going to need help – and who better to help her than her faithful old nursemaid?

Gone were the days when everything closed down if King Charles had a bad turn. From a powerful man with periodic delusions, he had dwindled into a predominantly childlike creature, only occasionally violently mad; a puppet-king to be manipulated by whoever guided his hand to sign the edicts. As a consequence, the palace was brimming with courtiers on the make, all looking to fill any official posts that might put them within reach of the pot of gold that was the royal treasury, which meant that accommodation was at a premium. If you lived in servants’ quarters, you had to earn them and therefore our whole family was employed in the royal household, even Luc.

In fact, he was the happiest of all of us, for although he was only eight, he was in his element as a hound boy in the palace kennel. He had grown into a bony-kneed, cheeky-faced lad with an affinity for animals like his father and a stubborn streak like me. I had tried hard to teach him the rudiments of reading and writing, but with an ambition to be a huntsman, he could not see the point. Alys had taken to her letters easily, but now had little time to practice since she worked in the queen’s wardrobe, where she hemmed linen from dawn till dusk. How she bore the tedium, I’ll never know but she’d grown into a docile, long-suffering little maid and I consoled myself that seaming was better than steaming, which was my unhappy lot. Since females were banned from working in the bake house or kitchens, where I might have used my skills to their best advantage, I was forced to become an alewife – the lowest of the low. I was used to hard work and fermenting barley was no harder than baking bread, but it was different when it wasn’t your own business.

The worst thing for me, living in the palace, was being constantly reminded of Catherine. I saw her face at the windows of the nursery tower, heard her laughter in the old rose garden and her footsteps on the flagstones of the chapel cloister. Only her imminent return looked set to stir me out of the deep, persistent melancholy I had been feeling without admitting it to myself.

The day after Jean-Michel dropped his bombshell, I went to the grand master’s chamber in the King’s House and, mercifully, my powers of persuasion did not desert me. Within minutes, the clerk charged with assembling staff for Catherine’s new household had agreed that I was ideally suited for work as her tiring woman and arranged for my transfer from the palace brewery. I would be on familiar ground, for she had been allocated the very rooms in which she had spent the first years of her life. We were both going back to the nursery tower. My feet scarcely seemed to touch the ground as I sped to my new post, gloating over the fact that soon, very soon, I would once more be as close as any mother to the child of my breast.

The first-floor chamber of the tower, once Madame la Bonne’s bedchamber, had been turned into a salon where Catherine and her companions would be able to read and embroider and entertain themselves and her visitors. The former governess’ crimson-curtained bed had been long ago removed and the chamber walls were hung with rainbow silks and jewel-coloured tapestries. It was furnished with cushioned stools, polished chests and tables and a carved stone chimneypiece framing a deep hearth, where a blazing fire would keep the air a good deal warmer than it had ever been in the old days. It was while I was lighting this fire a few days later, that the door opened without warning and a young lady entered and stood staring at me.

Catherine! I sank to my knees, glad to do so as my legs had turned to jelly. Dumbstruck, I gazed up at a vision of loveliness, dressed in a cornflower-blue gown, her beautiful Madonna face framed by neat little horns of netted blond hair and a filmy white veil.

‘Do not look at me, woman!’ the vision snapped. ‘I will not be gawped at by a servant.’

I flinched and lowered my eyes. A thousand times I had imagined a reunion with Catherine, but this reality jarred alarmingly. Everything looked as it should – the stylish velvet gown neatly trimmed with fur, the small oval face, the royal-blue eyes and the creamy complexion – but the sweet nature I remembered seemed to have vanished, the vibrant, loving spirit of the child had apparently withered into brittle pride. With a sinking heart I was forced to conclude that my darling, winsome girl had become a haughty mademoiselle.

‘Who are you?’ she demanded. ‘What is your name?’

‘Mette,’ I replied, struggling to control my shock.

‘Mette? Mette! That is not a name. What is your full name?’

I was prepared to forgive the fact that she had not known me by sight, but she had known my name as a toddling infant – surely she would not forget it. But I heard the cold scorn in her voice and I neither wanted nor dared to look up and see it in her eyes. Suddenly I was consumed with anger against the nuns of Poissy. What could they have done to destroy the gentle essence of my Catherine?

‘Guillaumette,’ I gulped and had to repeat the word to make it audible. ‘Guillaumette.’

I risked a fleeting glance. Not a flicker of recognition.

‘That is better. What you are doing here, Guillaumette?’ The lady began to patrol the room, peering at its hangings and furnishings, viewing them without any visible sign of approval.

‘I have been appointed your tiring woman, Mademoiselle. I thought you might need a fire after your journey,’ I said meekly.

‘In future, if you are needed you will be summoned,’ she declared, fingering the thick embroidered canopy of a high-backed chair as if assessing its market worth. ‘Servants should not loiter in royal apartments. Remember that. You may wait below in the ante-chamber.’

‘Yes, Mademoiselle,’ I murmured and scuttled for the door, as eager to leave as she clearly was to be rid of me.

I stumbled down the stairs in a state of disbelief. Of course I had considered it possible that Catherine might not remember me after such a long period of separation, bearing in mind how young she had been when we parted, but such an evident change in character was a tragedy. I felt as if my heart was being squeezed in a giant fist.

The ante-room where I had been ordered to wait was on the ground floor, off the main entrance. It had been a bare, cold room when Louis and Jean used to have their lessons there, but now there was a brazier to warm the draught from the door and a tapestry on one wall depicting a woodland scene, with benches arranged beneath. No candles had been lit however and only a few dusty beams of twilight slanted in through the narrow windows.

Such gloom echoed my mood. Angrily dashing tears from my eyes, I cursed myself for being so foolish as to believe that my former nursling would automatically greet me with warmth and joy. She had been sent to Poissy to be educated as a princess and royalty was used to receiving personal service from noble retainers. Courtiers fought amongst themselves for the honour of pulling on the sovereign’s hose or keeping the keys to his coffers. I knew that my duty as a menial servant was to be invisible, performing the grubbier tasks in my lady’s absence and, if caught in the act, turning my face to the wall and scuttling out of sight. To gaze directly at a princess and expect her to remember the affection she had shared with me as a child, had been to defy the social order. I might harbour a lifetime’s love for the tiny babe I had suckled, but there was no rule which said she must return the sentiment. Quite the reverse, in fact. She was far more likely to have closed her mind to her neglected past and embraced her glittering present. Downcast, I nursed my injured feelings and contemplated a future which seemed once more joyless and bleak.

7

‘Mette? It is Mette, is it not?’

I’d been huddled on a bench in the far corner of the ante-room, too wrapped in misery to look up when I heard someone open the door. Then the low, sweet voice startled me to my feet with such an acute pang of recognition it made my very bones tingle. A hooded figure stood hesitating in the doorway, the face in shadow.

‘Yes, Mademoiselle. It is Mette,’ I whispered, my hands flying to my breast where my heart was leaping and fluttering like a caged finch.

I caught a faint hint of indignation as she eased back her hood and asked, ‘Do you not know me, Mette?’

‘Oh dear God! Catherine!’ Tears swamped my eyes and I must have swayed alarmingly, for she rushed across the room and I felt her arms go around me, supporting me as my knees buckled. We fell together onto the bench.

Even the smell of her was familiar; the soft, warm, delicate, rosy smell of her skin was like incense to me. How could I have mistaken another for her? Every inch of my body knew her without looking, like a ewe knows her lamb on a dark hillside or a hen knows her chick in a shuttered coop.

‘You are here,’ she crooned. ‘I felt sure you would be. Oh, Mette, I have longed for this day.’

We drew back from our close embrace to study each other. The curves of her brow and lips were like glowing reflections of my dreams and even the gloom of the chamber could not leech the colour from those brilliant blue eyes. I gazed into their sapphire depths and felt myself submerged in love.

‘I have crawled on my knees to St Jude,’ I cried, my voice breaking on a sob, ‘asking him to bring us back together, but I never thought it would happen.’

Catherine gave a little smile. ‘St Jude – patron of lost causes. That was a good idea. And, you see, it worked.’ She shook her head in wonder, her eyes still roaming my features. ‘I have seen your face in my dreams a thousand times, Mette. Other girls at the convent pined for their mothers, but I pined for my Mette. And now here you are.’ Her arms slid around my neck and her soft lips pressed my cheek. ‘We must never be parted again.’

Her words were like balm to my soul. During those long years when I had secretly kept her image locked in my heart, she had also cherished mine. She was the child of my breast and I was the mother of her dreams. I could have crouched in that shadowy corner for ever, feeling her breath on my cheek, our hearts beating together.

‘Ah, you are here, Princesse. This lady said you had arrived.’

There were two figures outlined in the doorway against the light of the hall, but it was the aggrieved tones of the lady I would never forgive myself for mistaking for Catherine that shattered our idyll. Whoever she was, she came rushing forward, clearly horrified at finding the princess in close embrace with a servant. ‘For shame that this impudent woman should accost you, Mademoiselle! Let me have her removed. I fear she does not know her place.’

With her back to the door, Catherine rolled her eyes, gave my hand a reassuring squeeze and smothered a little giggle; that blessed giggle which had echoed in my head down the years. Then she stood up and turned to face the outraged newcomer. The real Princess Catherine was dressed more plainly – a drab hood and travelling mantle covering a dark robe – than the girl I had thought to be her, yet there was something in her carriage which made the haughty creature in her fashionable attire fall back.

‘On the contrary, she knows her place well. Her place is with me,’ my nursling told her, casting a hand back to encourage me to rise. ‘Her name is Guillaumette. Who are you?’

The haughty girl sank into a courtly obeisance; a skilled crouch which I presumed was of precisely the right depth to honour the daughter of the king. ‘Forgive me, Mademoiselle. My name is Bonne of Armagnac. The queen has appointed me your principal lady in waiting. She sent me to welcome you and to command you to attend her as soon as you have recovered from your journey.’

Catherine turned to me with an expression of exaggerated surprise. ‘Do you hear that, Mette?’ Her voice had suddenly acquired a crystal hardness which startled me. ‘My mother wishes to see me. There is a first time for everything.’ Then she stretched out her hand to the other girl, who still hovered uncertainly in the doorway, gesturing her forward. ‘Agnes, this is Guillaumette – my Mette about whom you have heard so much. Mette, this is my dear friend Agnes de Blagny, who has bravely agreed to accompany me to court. She and I have been close companions for the last four years, ever since Agnes came to Poissy abbey after she lost her mother.’

Agnes de Blagny was dressed like Catherine in a simple kirtle and over-mantle, with a plain white veil. I assumed it to be some sort of school habit worn by all the abbey pupils, but somehow Agnes did not wear it with the same easy elegance as her royal friend. She looked swamped and nervous, but she returned my smile with a shy one of her own.

‘There is no time to linger down here, Princesse!’ An older and more forceful female presence bustled into the room stirring dust off the flagstones with her flowing fur-lined mantle. ‘Court attire has been prepared for you. We will help you dress to meet the queen.’

Fittingly, it had been the Duchess of Bourbon who had fetched Catherine from Poissy, just as she had delivered her there nearly ten years before, and it was she who now made a brisk entrance, greeted Bonne of Armagnac graciously, gave me a dismissive glance, then swept all the young ladies off to Catherine’s new bedchamber, the room that had once been a day nursery but which was now transformed by silken cushions and hangings and some fabulous flower-strewn Flemish tapestries.

‘Do not go away, Mette,’ Catherine had whispered as she reluctantly left my side. Nothing could have made me leave, but I thought it prudent to keep a low profile, so I took up position on the stair just beyond the entrance to her bedchamber, carefully hidden by a turn in the spiral, and waited patiently, rendered impervious to the cold draughts by the knowledge that I was only a few steps from my life’s love.

When I next saw her, I might have been forgiven for not recognising her. She was encased in a weighty jewel-encrusted gown and mantle, her head crowned with gold and stiffened gauze. The stair was hardly wide enough to accommodate her voluminous skirts and the two noble ladies were too busy assisting her descent to notice me peering around the central pillar. The brief glimpse I had of Catherine’s face showed me rouged cheeks, stained lips and a wary, closed expression. In less time than it took a priest to say mass, they had turned my sweet girl into a painted doll. Agnes had been found a simpler court costume and scampered after the grand ladies like a little mouse. I did not think the timid school friend would make much of a mark at Queen Isabeau’s court.

I had plenty to occupy me as I waited for Catherine’s return. The chamber bore all the signs of a major upheaval. Her travelling clothes had been flung to the floor, brushes, combs and hair-pins were scattered on dressing-chests and pots of face-paints and powders had spattered polished surfaces. I set about restoring the chamber to the pristine condition in which I had left it and preparing for the return of what I was sure would be a drained and exhausted Catherine, lighting candles and setting glowing coals in a hot box to warm the bed. Guessing (correctly as it turned out) that the queen would have dined and would not think to offer Catherine any refreshment, I also set some sweet wine and milk to curdle near the fire and put out some wafers. As I worked, I tried to imagine what the conversation would be like between mother and daughter, meeting as strangers.

The candles had burned down several inches when a noise like birds twittering roused me from my sentinel stool. It was the high-pitched chatter of excited young ladies drifting up the stair and I swiftly retreated to my previous hiding place. Catherine’s retinue had obviously expanded and fortunately, as they tripped into the bedchamber, they left the door open, so I was able to hear Bonne of Armagnac’s authoritative voice begin allocating various tasks concerning Catherine’s toilette.

‘With your permission, Mademoiselle, Marie and Jeanne will help you to undress whilst I secure your robes and jewels …’

Catherine’s voice broke in, low and sweet but firm enough to silence her attendant. ‘No, Mademoiselle Bonne. You do not have my permission. What I would like you to do is call Guillaumette. She is the one I need to help me.’

‘Do you mean your tiring-woman, Mademoiselle?’ Bonne protested. ‘A menial cannot be trusted to handle your highness’ court dress or safeguard your jewels! That is a task for someone of rank.’

I smiled at the steely determination audible behind Catherine’s deceptively mild reply. ‘Mette is not “a menial”, as you put it, she is my nurse. When I was a child she was trusted with my life. I’m sure she can be trusted now with a few rags and baubles. Summon Guillaumette if you please.’

I heard my name called from the doorway and waited a timely minute before responding. Meanwhile Catherine was gently attempting to mollify her affronted lady-in-waiting. ‘You are older and wiser than I, Mademoiselle Bonne, but I suspect that even you have a nurse who cared for you in childhood and who knows all your little ways …’

‘Well, yes,’ Bonne of Armagnac admitted reluctantly, ‘but I thought …’ Her voice trailed away uncertainly.

‘… that mine would have long gone?’ Catherine suggested gently. ‘But you see my faithful Mette has not gone. She is here …’ As indeed I was, entering the salon exactly on cue and dropping humbly to my knee inside the door, head bowed to deflect the angry glare of Mademoiselle Bonne. ‘… and I have decided that she and she alone will have full charge in my bedchamber.’

I had to pinch myself to remember that she was not yet fourteen. I sent up a silent prayer of thanks to St Catherine, for it was surely she who had inspired this combination of sweetness and obstinacy in her namesake.

Peeping under the edge of my coif I watched Catherine stifle a yawn and say wearily to the assembled bevy of young ladies, ‘I am very tired. There will be much to do tomorrow. The queen seems to have commissioned half the master-craftsmen in Paris to fit me out for court life and I shall need all your advice on the latest fashions. So now I will bid you goodnight and I know you will show kindness and assistance to my friend Agnes de Blagny who, as you know, will be one of your number.’

I felt quite sorry for the timorous Agnes as she was carried off by four court damsels who obviously found the prospect of a day spent picking clothes and jewels so enchanting that their excited chatter died only gradually away down the stair. Bonne of Armagnac remained behind however, sidling up to Catherine and dropping her voice to a confidential murmur. I tactfully retired to the hearth to re-heat the curdled posset, but I have sharp ears and easily caught the gist of her speech.

‘Coming from the convent, Mademoiselle, you will need more than just advice on jewels and fashions. The ways of the court are complex. It is easy to make mistakes. The queen trusts me to help and guide you, just as my father helps and guides the dauphin.’

‘No doubt she does.’ There was a pause as Catherine gazed steadily at Bonne before continuing with the kind of regal assurance that I now believe cannot be taught. ‘And you may be sure that I will be as grateful to you as the dauphin is to your father, Mademoiselle. But I must remind you that the queen made an announcement at court tonight which you seem to have forgotten. As the only remaining unmarried daughter of the king, I am to have the courtesy title of Madame of France. I feel certain that you of all people will not want to continue making an error of protocol by addressing me as Mademoiselle. Now I wish you a very good night – and please leave the key to the strong-box.’

It was only later I learned that the key in question was tantamount to Bonne’s badge of office. It hung from her belt on a jewelled chatelaine and for a moment I thought she was going to refuse to hand it over. Then she unhooked it abruptly and dropped it on the table beside Catherine.

‘As you wish, princesse. Good night.’

‘Good night, Mademoiselle Bonne,’ replied Catherine, her painted court face unsmiling beneath the ornate headdress.

The Count of Armagnac’s daughter made one of her precise courtesies and stalked out, casting a baleful glance at me and leaving the door deliberately open. As I obeyed Catherine’s mute signal to close it, I heard the lady’s footsteps halt at the curve of the stairs and guessed that she had paused in the hope of catching some of our conversation. With a grim little smile I ensured that the only sound that carried to her ears was the firm thud of wood on wood.

‘Am I to address you as Madame then, Mademoiselle?’ I asked Catherine, confusing myself.

To my delight she giggled again. ‘Well, you certainly do not need to address me as both, Mette!’ she exclaimed. After a moment, she said, ‘I think I would rather you stuck to Mademoiselle. I seem to remember that when you called me a little Madame you were usually cross with me.’

‘I am sure I was never cross with you, Madamoiselle,’ I assured her. ‘You were always a good child, and you are scarcely more than a child still.’

She raised a quizzical eyebrow at me.

‘You may not know, Mademoiselle,’ I said, crossing to the hearth to pour the warm posset into a silver hanap, ‘that while you were away there was much political upheaval and at one time the Duke of Burgundy ordered a number of the queen’s ladies to be imprisoned in the Châtelet. Mademoiselle of Armagnac was among them. It is said that their gaolers abused them and I know that they were mauled and mocked by the mob on the way there. She can have no love for commoners like me.’

Catherine gazed at me steadily for several moments before responding. ‘See how useful you are to me already, Mette,’ she remarked. ‘Who else would have told me that?’

I placed the hanap on the table beside her and began removing the pins that fastened her heavy headdress.

As I lifted away the headdress, she briefly massaged an angry red weal where the circlet had dug into her brow, then she cupped her hands around the hanap and took a sip. ‘Now I will tell you something that you may not know, Mette. Mademoiselle Bonne has recently become betrothed to the Duke of Orleans, he who was supposed to marry Michele but ended up marrying our older sister Isabelle. I went to their wedding when I was five but unfortunately she died two years later in childbirth. I prayed for her soul, but I did not weep because, as you know, I hardly knew her. The queen was at pains to tell me all about Bonne’s betrothal this evening. Apparently Louis does not allow his wife Marguerite to come to court because he hates her for being the Duke of Burgundy’s daughter, so when Bonne marries Charles of Orleans, she will be third in order of precedence after the queen and myself.’

Fast though news spread in the palace, this gossip had not yet reached the servants’ quarters. The present Duke of Orleans was the king’s nephew, heir to the queen’s murdered lover. His Orleanist cause had benefited greatly from the Count of Armagnac’s military and political support, and this marriage would be the pay-back, bringing Bonne’s family into the magic royal circle. Mademoiselle Bonne was definitely a force to be reckoned with and I feared that, by showing me favour, Catherine had already irretrievably soured relations with her.

I bent to unfasten the heavy jewelled collar she was wearing and she put down the posset and raised her hand to my face, pushing under my coif to trace the two puckered scars that ran from cheekbone to jaw.