Полная версия

The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom

Life for the villagers was tough enough without having to put up with this, and around 1610 they attempted to oust their austere rector. ‘The calling of a Minister, is a painful and laborious, a needful and troublesome calling,’ Attersoll lamented.21 Nevertheless, he was not prepared to go, and appealed for help to Sir Henry Fanshaw, another scholar and his mentor at Cambridge, who had since become an official in the Royal Court of Exchequer.

The manner of Fanshaw’s intervention is unknown, but it was successful, and Attersoll would continue as rector of the parish for decades to come. Perhaps as a snub to his parishioners, and probably encouraged by the appearance of King James’s Authorized Version of the Bible in 1611, he devoted more time than ever to biblical analysis, producing a number of hefty tomes over the next eight years: The Historie of Balak the King and Balaam the False Prophet (1610), an exposition on the Old Testament Book of Numbers that continued The Pathway to Canaan of 1609; A Commentarie vpon the Epistle of Saint Pavle to Philemon (1612); The Neuu Couenant, or, A treatise of the sacraments (1614); and a massive combined edition of his expositions on Numbers, the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses, in 1618. This was prolixity even by Puritan standards, in the case of the commentary on St Paul’s letter to Philemon, five hundred plus pages arising from just one in the Bible.

He was working on the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses when his daughter Mary appeared at his doorstep, carrying his infant grandchild Nicholas. Attersoll was unlikely to have welcomed the interruption, particularly as he may have been expecting the Culpepers to provide for his widowed daughter. Sir Edward Culpeper had innumerable properties scattered across his Sussex estate, including many close to Attersoll’s parish. Any one of these would have provided a comfortable home for Mary and her fatherless boy. Perhaps such offers had been made, and Mary had declined them in preference for her father. If that was so, the decision was one both he and she would come to regret.

Whatever the circumstances of Mary’s arrival in Isfield, Attersoll had no option but to accommodate mother and child in the cramped rooms of his ‘cottage’ and assume responsibility as Nicholas’s guardian. Being but a ‘poor labourer in the Lord’s vineyard’, the extra cost of having to provide once more for a daughter and now a baby must have a put a strain on Attersoll’s finances, and exacerbated the bile that had built up over his material circumstances.22

There is no mention of Attersoll’s wife at the time Nicholas was in Isfield, suggesting that he was a widower and had been living alone. He had at least one son, also called William, but he was at Cambridge at the time of Mary’s return to the household, preparing dutifully to follow his father into the Church. The university fees and maintenance costs would have added a further strain on the old man’s fixed income.23 This must have made the presence of a child in the midst of Attersoll’s cloistered, scholastic world all the more disruptive.

He certainly did not like children. ‘We see by common experience, that a little child coming into the world, is one of the miser-ablest and silliest creatures that can be devised, the very lively picture of the greatest infirmity that can be imagined, more weak in body, and less able to help himself, or shift for himself, then any of the beasts of the field.’ Looking at an infant, all he could see was the image of men ‘through sin & their revolt from God fallen down into the greatest misery, and lowest degree of all wretchedness’.24

Nevertheless, the care of children was a theme of great concern to him, because it related not only to the children of parents, but also to the children of God. Protestantism was a rebellion against the father-figure of the Pope (whose very title was derived from ‘papa’, the childish word for father). Some Protestants saw this as a liberation, allowing every Christian to find their own way to Christ, carrying the Bible and their sins with them, like Bunyan’s burdened hero in The Pilgrim’s Progress. But it worried Attersoll greatly. He saw ‘godly’ Protestants as being like the Israelites of the Old Testament, escaping the tyranny of the Pope just as the Jews had thrown off the tyranny of the Pharaoh. But the Jews had needed their Moses to guide them to the Promised Land.25 This is what drew Attersoll to the study of Numbers, the fourth book of the Bible, and the penultimate section of the ‘Pentateuch’, the five books said to have been dictated directly to Moses by God. Numbers told the story of the Israelites in the Sinai desert, and Attersoll noted how, as they gathered there, they ‘murmured’ against Moses. Led by Korah, Datham, and Abi’ram, they became idolatrous, conspiring and threatening to destroy, as Attersoll put it, the ‘order and discipline of the Church’ – his intentionally anachronistic term for the religious organization around the Tabernacle, the portable structure used by the Israelites as their place of worship during the Exodus.26 ‘Thus … the wicked multitude usurped ecclesiastical authority,’ Attersoll railed, ‘and endeavoured to subvert the power of the Church-government, and to bring in a parity, that is, an horrible confusion.’ The wicked multitude of his own parish had done the same thing, as had others across the country. All around there were rebellions and usurpations, and there was a social as well as religious need for figures of authority. ‘Magistrates and rulers are needful to be set over the people of God,’ he wrote. They are the ‘father[s] of the country’. Similarly, though ministers of God like himself were no longer called padre, fatherhood was still their role: ‘The Office of the Pastor and Minister of God, is an Office of power and authority under Christ.’27

And here before him was a little child who, like the Protestant children of God, was without a father. It was his responsibility to take on the role.

The model father was, of course, God. In some moods, this meant for Attersoll a New Testament God: embracing, protective, tolerant. Parents should offer their children ‘good encouragement in well doing’, he wrote, as little Nicholas played around his feet. ‘We are bound to praise and commend them, to comfort them, and to cheer them up.’ Of primary importance was education. Uncultivated childish minds ‘bring forth cockle and darnel’, weeds that grow in cornfields, ‘in stead of good corn’. However, many parents ‘do themselves through humane frailty and infirmity sometimes fail in the performance of this duty’, he noted. They ‘cocker’, pamper, their children ‘and are too choice and nice over them, they dare not offend them, or speak a word against them’. This ‘overweening and suffering of them to have their will too much, God punisheth in their children’ by making them rebellious. So, for the ‘right ordering and good government’ of the home, children must be taught, and their first lesson should be in godly discipline. Here, an Old Testament tone emerged. Youth must ‘learn to bear the yoke of obedience’, and it was the responsibility of parents to place it upon their shoulders: ‘If we have been negligent in bringing [children] unto God, and let them run into all riot, and not restrained them, we have cause to lay it to our consciences, and to think with our selves, that we that gave them life, have also been instruments in their death.’28

Nicholas was in some respects a good student of Attersoll’s lessons. As his work in later life would show, he read the classics and scriptures conscientiously, and became mathematically adept. Attersoll also had interesting and unexpected things to say on such matters as astrology and magic. He had an academic, if not practical, knowledge of the stars, noting that they mirrored the hierarchy of heaven and earth in that they ‘are not all of one magnitude, but there is one glory of the Sun, another of the Moon, and another of the Stars for one star differeth from another star in glory’.29

Discipline was more of a problem. The sparse documentation that survives does not provide details, but young Nicholas did not accept the yoke of obedience willingly. ‘The same affection that is between the Father and the Son, ought to be between the Minister & the people committed unto him,’ Attersoll wrote optimistically in 1612.30 Practical experience seemed to suggest a more negative equation. Just like the villagers of Isfield, Nicholas did not feel affection for his surrogate father, and would not do as he was told. Rumours persisted into his adulthood that Attersoll resorted to locking the boy up in his chamber, and leaving him in the dark.31

Lessons had to be learned, and Attersoll was uncompromising. The Bible was held over the boy, and its message battered into his head. God, like kings, expected unconditional obedience. Those set over us are put there by God, and it is his will that we submit to them, Attersoll believed. ‘Evil parents are our parents, and evil Magistrates are Magistrates, and evil Ministers are Ministers’, and, though he dare not write it, evil kings are kings – the position that underlay the belief of England’s monarchs since Henry VIII in their divine right to rule and expectation of unquestioning obedience from their subjects. ‘Servants are commanded to be subject to their masters, not only unto them that are good and gentle, but them that are froward [perverse], so ought children to yield obedience unto their fathers.’32

Underlying this tough message was Attersoll’s belief in predestination. This was one of the central tenets of Protestant theology, and at the time Attersoll was writing accepted by both the established Church and Puritan radicals.33 God, went the argument, must know in advance who will be saved – the ‘elect’, as theologians called them – and who will be damned. If he did not, then it meant he did not have perfect knowledge of the future, which suggested that his divine powers were limited. Attersoll found confirmation of this principle in the Book of Numbers. The book took its name from the census performed by Moses when the Israelites entered the wilderness of Sinai. ‘We learn from hence,’ argued Attersoll, ‘that the Lord knoweth perfectly who [his people] are.’ But his people, being but human and without perfect knowledge, do not know if they are among the elect. The signs were in their behaviour, which showed whether they tended towards godliness or wickedness. For example, rebellious acts, obstructions in the river of godly authority flowing from heaven, were symptoms of a wicked disposition.

In this fateful atmosphere, every act was subjected to providential scrutiny. The most trivial prank could mean the child was doomed, as deadly a sign as a cough indicating consumption. And whichever destiny was signified, salvation or damnation, nothing could be done about it. ‘God keepeth a tally … & none are hidden from him, none escape his knowledge, or sight.’

No absolution could be provided, no repentance sought, no comfort or consolation given. Every time Nicholas broke the ‘bands asunder’ and cast off ‘the cords of duty and discipline’, and the admonishing finger directed him into the dark, it was not the bogeyman who awaited him there, but Satan.34

The daylight world of the scullery was Nicholas’s escape from this predestinarian tyranny. This was where the women were, his adoring mother Mary, wives from the village, the maid. Here, salvation and damnation were replaced by blood and guts. Peeping over counter-tops, crouched in a corner, scurrying alongside blooming skirts, he could watch the preparation of meals and medicines, the skinning of a ‘coney’ (rabbit), its fur being dipped in beaten egg white and applied to heels that were ‘kibed’ or chapped by worn and ill-fitting shoes; cowslips being candied in layers of sugar; tangles of fibrous toadflax being laid in the water bowls to revive ‘drooping’ chickens.35

No fear of religious instruction here. Women were not expected to engage in such pursuits, at least not in Attersoll’s household. He acknowledged that there were ‘many examples of learned women’, his own daughter perhaps among them; but the Bible ‘requireth of them to be in subjection, not to challenge dominion’ of male discourse. The ‘frailness and weakness’ of their sex made them ‘easier to be seduced and deceived, and so fitter to be authors of much mischief’.36 Their place was in the pantry, their role to preserve the frail body, while the male ministry of Attersoll administered to the soul.

Thus, in the company of women, Nicholas encountered the more practical arts of nurturing and healing. Food and physic, chores and hygiene, were inextricably entwined. Here Mary, her awareness sharpened by the tragedy in Ockley, would treat wounds and mix medicines, as well as feed the family and clean the house, using traditional recipes, ingredients and methods handed down the generations, or shared through the village.

The supplies needed to sustain this regime all came through the back door, and it was a young boy’s job to go and fetch them. Outside lay one of the most beautiful and botanically rich areas of the country, a fertile valley on the southern fringes of the Ashdown Forest, the enchanted place into which future generations of children were enticed when A. A. Milne made it the setting for Winnie the Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood. This landscape became Nicholas’s catechism, the meadows and woods his Sinai desert, the local names of medicinal flowers and shrubs his census of the elect. He attained an intimate botanical knowledge of Sussex, learning, for example, where to find such ingredients as ‘fleur-de-luce’ (elsewhere known as wild pansy, orris, love-in-idleness, and heartsease, the constituent of Puck’s love potion in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and ‘langue-de-boeuf’ (bugloss or borage), noting in later life how their ‘Francified’ names echoed the Norman invasion, which had taken place in 1066 at nearby Hastings.

He heard the women talk of the use of lady‘s mantle to revive sagging breasts, syrup of stinking arrach37 to ward off ‘strangulation of the mother’ (period pains), honeysuckle ointment to soothe skin sunburned by summer days in the fields. They talked of ‘kneeholm’ (‘holm’ is the Old English for holly), ‘dogwood’, ‘greenweed’, and ‘brakes’, the local names for butcher’s-broom, common alder, wold, and bracken. He discovered how every plant had its use, even one as predatory and toxic as brakes. Bracken was, and is, everywhere in Sussex. He would find it erupting in nearby woodland, wherever the undergrowth was disturbed by human activity, harassing stockmen who, during parched summers, would have to drive their animals away from grazing on its fronds, which are suffused with a form of cyanide. Yet the roots, bruised and boiled in mead or honeyed water, could be applied to boys’ itching bottoms to get rid of threadworm. A shovel-load of the burning leaves carried through the house would drive away the gnats and other ‘noisome’ creatures that ‘molest people lying in their beds’ in such ‘fenny’ places as the Sussex lowlands.38

In the graveyard of his grandfather’s church he would pick clary,39 a wild sage, the leaves of which, battered and butter-fried, helped strengthen weak backs. Wandering further up the valley towards the neighbouring village of Barcombe, following the lazy course of the Ouse, negotiating the network of sluices and ditches draining off into the river, he would visit a clump of black alder trees standing next to the brooks and peel back the speckled outer bark to reveal the yellow phloem, or inner bark. Chewed, it turned spittle the colour of saffron; sucked too vigorously, or swallowed, it provoked violent vomiting; but boiled with handfuls of hops and fennel, the grated root of garden succory, or wild endive, and left for a few days, it turned into a bitter, black liquor which, taken every morning, drew down the excess of phlegm and bile that during winter accumulated in the body like the floodwater in the fields outside.

In these fields, he pored over the book of nature in the same fine detail as his grandfather combed the book of God inside. However, when Nicholas was ten, his days of wandering the countryside came to an abrupt end. Attersoll decided the boy needed a more formal education. He was packed off to a Sussex ‘Free School’ ‘at the cost and charges of his mother’ – probably the grammar school in Lewes, six miles away, or perhaps further afield, where he could no longer disturb his grandfather’s work.

Attersoll had also decided upon a vocation for the boy. ‘Every one must know & learn the duties of his own special calling,’ he wrote, and, like Attersoll’s more dutiful son William junior, Nicholas’s was to be the Church. At school, he would learn Latin, a prerequisite for an education in divinity, and a preparation for university.40

Nicholas was sent to Cambridge in 1632, when he was sixteen years old. Little is known about his time there. He may have gone to his father’s college, Queens’, or to his grandfather’s, Peterhouse.41 In any case he would have followed the standard curriculum of the time, covering the seven ‘liberal arts’ – first the core subjects of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, followed by arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy. The way these subjects were taught rested on the authority of the text. Teachers would read out sections from set books, mostly by classical authors, all in Latin, elucidating where necessary. These were gospel. Students were not expected to question or challenge them, only to study and gloss them.

Nicholas’s mother had given him £400 for his ‘diet, schooling, and being at the university’. This was a lot of money, and it is not clear where she got it from – certainly not from the ‘poor labourer’ Attersoll, nor from her late husband’s estate (Nicholas senior’s short career more likely diminished than increased his £120 inheritance). Perhaps it was donated by a benefactor, a Culpeper relative such as Sir Edward’s son William, who had recently inherited his father’s title and estate and would later be described by Nicholas as a godfather figure. Or it may have come from a member of the local gentry to whom Attersoll dedicated his books, such as Sir John Shurley, owner of Isfield Manor.

Wherever it came from, £400 was enough for a comfortable life, leaving a sufficient surplus after board, lodging, and fees for a young student, later famous for his ‘consumption of the purse’, to develop an indulgence, such as smoking tobacco.

Nicholas’s passion for smoking was legendary. Even friends accepted that he took ‘too excessively’ to tobacco. It was the rage in 1630s Cambridge, attracting ‘smoky gallants, who have long time glutted themselves with the fond fopperies and fashions of our neighbour Countries’ and were ‘desirous of novelties’. Smoke-filled student chambers and taverns were an exhilarating change from the stuffy rooms of his grandfather’s cottage, and so were the apothecary shops that acted as the main outlets for tobacco, with their snakeskins and turtleshells in the window, and smells of incense, herbs, and vinegars inside.

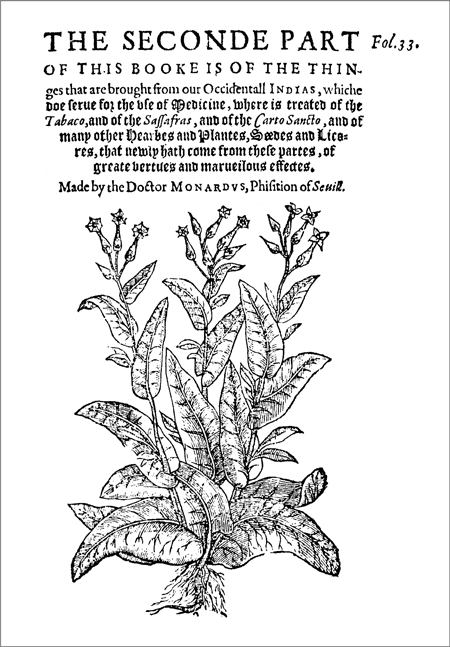

Tobacco had been in the country since Elizabethan times. Its introduction to England is attributed to Sir Walter Raleigh, but it was already known before Raleigh’s voyages to America in the 1580s. In 1577, an English translation of an influential herbal by the Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes appeared under the poetic title Ioyfull Nevves out of the Newe Founde Worlde. An entry for ‘the Tabaco, and of his great virtues’ appeared prominently among a variety of exotic discoveries, such as ‘Herbs of the Sun’ (sunflowers), coca, and the ‘Fig Tree from Hell’. Monardes dwelt mostly on tobacco’s medicinal virtues (he claimed it was effective for treating headaches, chest complaints, and the worms), which he had exploited in his own practice in Seville. But he also included a detailed and scintillating report of a religious ritual performed by ‘Indian priests’ in America that had been observed by Spanish explorers. The priest would cast dried tobacco leaves upon a fire and ‘receive the smoke of them at his mouth, and at his nose with a cane, and in taking of it [fall] down upon the ground, as a dead man’. ‘In like sort,’ Monardes added, ‘the rest of the Indians for their pastime do take the smoke of the Tabaco, for to make themselves drunk withal, and to see the visions, and things that do represent to them, wherein they do delight … And as the Devil is a deceiver, and hath the knowledge of the virtue of herbs, he did shew them the virtue of this herb, that by the means thereof, they might see their imaginations, and visions, that he hath represented to them, and by that means doth deceive them.’ For this reason, Monardes placed the herb among a class of herbs ‘which have the virtue in dreaming of things’, hallucinogenics such as the root of ‘solarto’ (Belladonna or Deadly Nightshade), which, taken in wine, ‘is very strange and furious … and doth make him that taketh it dream of things variable’. Such properties encouraged English merchants with Spanish contacts to source samples of the herb for an eager market back home. The translator of Ioyfull Nevves, John Frampton, noted in the book’s dedication to the poet and diplomat Edward Dyer how the ‘medicines’ Monardes mentioned ‘are now by merchants and others brought out of the West Indies into Spain, and from Spain hither into England, by such as do daily traffic thither’.42

The tobacco plant featured in Nicolas Morandes’s herbal.

England, however, was at war with Spain during the latter years of the sixteenth century, and tobacco remained a rarity. That all changed in the 1620s, when bountiful supplies of a sweet, pungent variety, superior even by Spanish standards, began to be cultivated in England’s newly-established colony of Virginia in North America, fuelling a surge in consumption.

The sudden spread of such a potent herb among the young alarmed the authorities. In the House of Commons, knights of the shires demanded that it be banned ‘for the spoiling of the Subjects’ Manners’. In his Directions for Health, first published in 1600 and one of the most popular medical books of the time, William Vaughan warned against the ‘pleasing ease and sensible deliverance’ experienced by young smokers, and, targeting his health-warning at the area that was likely to cause them greatest concern, urged them ‘to take heed how they waste the oil of their vital lamps’. ‘Repeat over these plain rhymes,’ he instructed:

Tobacco, that outlandish weed,

It spends the brain, and spoils the seed:

It dulls the sprite, it dims the fight,

It robs a woman of her right.43

The sternest critic was King James himself. In 1604, he published his Counterblaste to Tobacco, in which he condemned the ‘manifold abuses of this vile custom of tobacco taking’. ‘With the report of a great discovery for a Conquest,’ he wrote, recalling Sir Walter Raleigh’s voyages to colonize Virginia, ‘some two or three Savage men were brought in together with this Savage custom. But the pity is, the poor wild barbarous men died, but that vile barbarous custom is yet alive, yea in fresh vigour.’

The King was particularly affronted by the medicinal powers claimed for the plant. It had been advertised as a cure for the pox, for example, but for James ‘it serves for that use but among the pocky Indian slaves’. He examined in detail its toxic effects, displaying an impressive grasp of prevailing medical theories. Following the intellectual fashion of the time, he also drew an important metaphorical conclusion about his own role in dealing with such issues: he was ‘the proper Physician of his Politic-body’ whose job was ‘to purge it of all those diseases by Medicines meet for the same’.

But even the efforts of an absolute monarch could not stop the spread of this pernicious habit. ‘Oh, the omnipotent power of tobacco!’ he fumed, consigning it to the same class of intractabilities as religious extremism: ‘If it could by the smoke thereof chase out devils … it would serve for a precious relic, both for the superstitious priests and the insolent Puritans, to call out devils withal.’44

His ravings had no effect on consumption. Imports of tobacco boomed: 2,300 pounds in 1615, 20,000 in 1619, 40,000 in 1620, 55,000 in 1621, two million pounds a year by 1640.45 The more popular it became, the more James found that even he could not do without it. ‘It is not unknown what dislike We have ever had of the use of Tobacco, as tending to a general and new corruption, both of men’s bodies and manners,’ the King announced in a proclamation of 1619; nevertheless, he considered ‘it is … more tolerable, that the same should be imported amongst many other vanities and superfluities’ because, without it, ‘it doth manifestly tend to the diminution of our Customs’.46 In other words, the health risks of smoking were less important than his need for money.