Полная версия

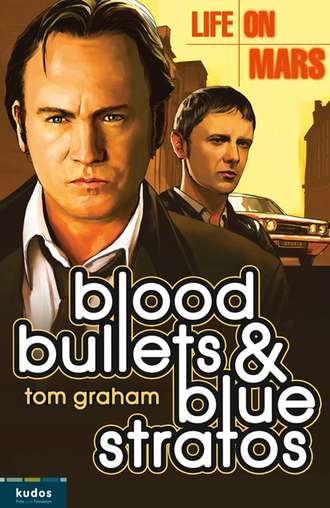

Life on Mars: Blood, Bullets and Blue Stratos

And, stationed as ever behind the bar, like a skipper at the helm of his ship, was Nelson, all gleaming teeth and proud dreadlocks and overflowing Jamaican charm. He looked up as Gene, Sam, Ray and Chris bundled noisily into his pub, and, like an actor on cue, he immediately fell into his regular routine. He grinned like a big, black Cheshire cat, planted his heavily bejewelled hands in readiness on the beer pumps, and sang out, ‘Well, here dey are again, da boys in blue. You must really love dis place.’

‘Home from home,’ growled Gene, planting himself at the bar. ‘You got four horribly sober coppers on your premises, Nelson. Remedy the situation – pronto.’

‘Sober coppers?’ said Nelson from behind the bar, rubbing his chin and raising his eyes in a mime of deep thinking. ‘Sober coppers? Now dare’s a thought.’

Ray lounged casually beside Gene, fishing an untipped Woodbine from behind his ear and sparking it up. Chris hovered uncertainly nearby, still quiet and withdrawn after his morning of undignified trouserless adventures.

But Sam felt distant. He had no heart for drinking with the boys tonight, not even after the deadly events of that morning. Cheating death had pumped Gene and Ray up nicely, leaving them feeling indestructible, like a couple of fag-stained Mancunian James Bonds. Chris had been badly shaken up, but was stronger and more resilient than even he himself believed, and would soon be back to his usual youthful self. But for Sam, the whole business with the shootout and the bomb had heightened his sense of vulnerability. It had stirred up deep and yet nameless feelings that he could not share with the boys. Annie was the one who would understand him. And, if she didn’t understand, then she would at least listen to him without constantly interrupting and taking the piss.

He had tried to make his excuses and avoid coming out with the lads tonight, but his presence at the Railway Arms this evening had proved to be non-negotiable. In the end, it was easier just to give in than keep arguing.

‘You go ahead and join them for a drink, Sam,’ Annie had told him, leaning across his desk in CID. ‘I’ll drop by the Arms later, once you boys have wetted your whistles.’

The sudden close proximity to her had made Sam’s heart turn over. She was fetchingly turned out in a salmon-pink waistcoat neatly buttoned over a cream turtleneck sweater; nothing showy, nothing sexy – practical work clothes for a day at CID – and yet somehow all the more alluring for their ordinariness.

‘But I want to talk to you, Annie,’ Sam had said.

‘Then talk to me.’

She subtly flicked her chestnut hair and the abundant curls above her shoulders bounced gracefully. Sam swallowed.

‘I can’t talk here,’ he said.

‘Okay. We’ll talk later, at the pub.’

‘At the pub? With Gene and Ray looking over our shoulders? And Chris banging on about his near-death experience in the toilet?’

‘I see what you mean.’

‘We need some real time, Annie. You-and-me time.’

‘Then we’ll make time, Sam – one way or another.’

At that moment, Annie had looked up at him with such a sweet and serious expression that Sam had felt the sudden reckless compulsion to lean forward and kiss her. And, if the boys in the department shrieked and wolf-whistled like a pack of adolescent schoolboys, so what?

But his nerve failed him and he hesitated. By then the moment had passed and Annie had turned and headed back to her desk, the opportunity – as ever – lost. As she walked away from him, Sam had felt that same pang of loss he always experienced when she was away from him. To be apart from her was far harder than being apart from the world he’d once come from – the yet-to-be world of 2006 that existed only in his memory, the world he had striven so painfully to return to, believing it to be home, only to find when he got back there that it was a foreign country, devoid of feeling and vitality, a place without meaning, without colour, without life. The shoddy, backward, nicotine-stained world of 1973, for all its faults and flaws, was at least alive – and, what was more, it had Annie in it, the bright, steady light at the centre of his strange and dislocated life.

But, even so, something was troubling him. It was a feeling he could not put into words, a vague but persistent sense that something was calling to him, summoning him, urging him to move on. It continually preyed on his mind. In the thick of his police work he could forget all about it, focus solely on his job – but the moment he glimpsed Annie the feeling would return.

And now, in the aftermath of their brush with death, those same feelings had returned with a vengeance. Here in the smoky confines of the Railway Arms, with Nelson grinning knowingly at him from behind the bar, he felt that sense of longing deep within him, a feeling like homesickness, or nostalgia, but at the same time unlike them. Indescribable. Unfathomable.

Sam’s reverie was shattered as Nelson slammed down four pints of bitter.

‘Here ya go, gentlemen,’ he grinned. ‘That’ll put hair on ya chest.’

‘Hear that, boys?’ said Gene, lifting his pint. ‘I’ll make a man of you all yet.’

‘Not if you get us shot first,’ Sam said, looking wearily into the froth of his beer. ‘You’re a liability, Guv, the way you carry on.’

‘Oh, do put a sock in it, Samuel. If I’d listened to you this morning, we’d all still be sitting around waiting for Bomb Disposal to show their faces.’

‘You’re not the sheriff of Dodge City, Guv. You can’t just go running in, blazing away, whenever you feel like it.’

Gene glugged his pint, licked away a beer moustache, thought for a moment, and said, ‘Actually, Sam – I can.’

‘No, you can’t. Running around like Clint Eastwood puts everyone in danger. You’ve got a duty of care to fellow officers as well as the public.’

‘I sometimes wonder why you got into this job, boss,’ Ray put in, halfway through his pint already. ‘It’s almost like you don’t enjoy it.’

‘I know I’m banging my head against a brick wall with you guys, but things have got to change in this department,’ Sam said. ‘You understand what I’m saying, Chris, surely.’

‘Why me, boss?’ Chris frowned.

‘Because you nearly died today.’

‘Don’t remind me!’

‘But that’s the point,’ Sam ploughed on. ‘This job, it ain’t a joke. It’s serious. People get hurt – and not always the ones that deserve it.’

‘I think we’ve all had enough of your speeches for one day, Tyler,’ Gene put in. ‘This is a pub, not a bloody pulpit. Save the sermons for that soppy bird Cartwright you’re always sniffing after. Nelson, we need chasers with these pints. Doubles – on the double!’

Nelson reached towards the optic holding an upturned bottle of Irish whiskey.

‘I ain’t touching that stuff!’ pouted Chris. ‘I ain’t touching anything Irish, not never again – whiskey, spuds, leeks …’

‘Leeks are Welsh,’ said Sam.

‘Don’t care. I’m not taking any chances.’

‘And I’m not dying of thirst just because you tripped over your own knickers this morning,’ declared Gene. ‘Nelson – four Scotches. Scotches, Chris, you listening? Jock water, not Paddy piss.’

Nelson obliged with four shot glasses of Scotch whisky.

‘Scots are as bad as the Irish,’ muttered Chris, but he grudgingly agreed to join the others in knocking them back.

‘Your prospective bit of leg-over Annie’s been earning her pennies today,’ said Gene, blowing smoke at Sam through his nostrils. ‘She’s been doing some productive police work – unlike some, Christopher.’ Again, Chris averted his face. ‘Looks like she’s come up with a juicy lead, a possible link in the Paddy chain.’

‘The what chain?’ frowned Ray.

‘I’ll show you,’ said Gene, and he planted an empty whisky glass on the bar. ‘This glass is a bunch of Paddies over in Ireland, stashing up guns and explosives. And over here’ – he plonked down another glass, twelve inches from the first – ‘is another bunch of Paddies, but this lot’s on the mainland, all Guinnessed up and looking to blow eight barrels of shite out of anything with a Union Jack fluttering out the top of it. What links this bunch of Paddies to this one is this’ – he placed a smouldering dog end between the two glasses – ‘the link in the chain, the couriers fetching the goodies from over the water and supplying the terrorist cells on the mainland. Now, Annie’s dug up a likely ID for that middle link, a husband-and-wife double act, and – no surprises here – Paddies an’ all. Looks like they might have been involved in supplying the fireworks for this morning’s fun and games.’

‘If it was the IRA,’ said Sam. ‘I’m not so sure it was anything to do with them.’

Gene threw his head back and rolled his eyes to the fag-stained ceiling. ‘Oh, Christ, not all this again.’

‘Think about it, Guv,’ Sam pressed on. ‘The hand painted on the wall – the letters RHF …’

Gene exhaled smoke like a bored and rather tetchy dragon. Sam looked to Chris and Ray for support, but neither of them looked much impressed.

‘I’m sticking to my guns on this,’ Sam insisted. ‘We’re dealing with some kind of terrorist organization, but it’s not the IRA. Even the way the explosives were rigged up – in a toilet for God’s sake! It doesn’t smell of the Provos to me.’

‘Chris was certainly smelling of the Provos when he jumped off that khazi,’ grinned Ray.

‘That ain’t fair, I was keeping it in,’ protested Chris.

‘We all saw the inside of your drawers this morning, Christopher,’ put in Gene. ‘Barry Sheene don’t leave so many skid marks.’

Nelson leant close to Sam’s ear and whispered, ‘I’d not be botherin’ tryin’ to talk sense to these boys, Sam – not tonight I wouldn’t. They ain’t in da mood.’

‘You’ve got that right, Nelson,’ said Sam, and he took a slug of bitter.

It was at that moment that Annie appeared, stepping out of the night into the warm glow of the pub. She had wrapped herself in a brown leather coat, pulling the wide collar up around her neck to keep out the cold. As if to greet her, the Rolling Stones’ ‘Angie’ sobbed from the loudspeakers behind the bar:

Seeing her round face, with its Harmony hairsprayed curls and warm, mischievous eyes, Sam once again felt a sudden stirring of his heart. He told himself to stop being so adolescent, that he was too old for such gushing, seething emotions.

But then Annie glanced across at the bar, caught his eye, and at once her face lit up. It made Sam’s heart beat a little faster – for a brief second, he felt he was the king of the world – and he forgave himself such a schoolboy response to her. It felt too good to feel bad about.

Annie clip-clopped over in her heeled boots and examined the four pints and four empty shot glasses crowding the bar.

‘Taking it easy tonight, are we?’ she said.

‘Nelson – another round of pints!’ ordered Gene. ‘And some sort of poofy squash for the bird.’ Turning to Sam he said, ‘Don’t let us stop you taking your pint and totty to another corner, Sam.’

‘Why’d you say that?’

‘A lifetime in the force, Sammy – it’s made me sensitive to picking up vibes. And I’m picking up vibes right now – ones that say you and her would rather be alone just now.’

‘Well, Guv, I would like a chance to be with Annie in private. You know, for a little tête-à-tête.’

‘I’ve never heard it called that,’ muttered Ray. Chris sniggered.

‘Here you go,’ grinned Nelson, passing over drinks. ‘A rum and Coke for the lady of my dreams, and a fresh pint o’ me finest for me good friend Samuel.’

‘Clear off with her and have your chinwag – you’re bugger all company tonight,’ Gene ordered. ‘Just make sure you’re both bright-eyed and bushy-tailed in the morning – we’ve got an IRA arms-smuggling chain to break.’

‘The incident this morning, Guv – it wasn’t the IRA,’ said Sam.

‘Discuss it with WPC Crumpet,’ Gene replied flatly. ‘I’ve got a liver to abuse.’

And, as Sam and Annie carried their drinks away, he lifted his glass in a toast to them, growled, ‘Cheerio, amigos,’ and tossed three fingers of neat whisky down his gullet.

‘Sometimes,’ Sam whispered as they walked away, ‘sometimes, Annie, I really do think seriously about killing him.’

‘The guv?’ Annie smiled back. ‘You’d have your work cut out. I reckon you’d need a silver bullet. Or a stake through the heart.’

‘Or an atom bomb,’ said Sam. ‘Come to think of it, he’d probably survive – him and the cockroaches.’

‘And he’d be radioactive. He might go all big like Godzilla.’

‘Oh, God, Annie, not even in jest …’

They settled themselves into a corner, the Rolling Stones still weeping from the speaker on the wall above them.

‘Well then,’ said Annie, ‘here we are, having our moment, just the two of us.’

‘I was hoping for something a little bit more … A little less …’

They both glanced briefly at Gene, Ray and Chris sharing a filthy joke only feet away. Ray was using his hands to describe the shape of some sort of enormous saveloy in the air.

‘Just carry on like they’re not there,’ said Annie. ‘Believe me, Sam, that’s what I do. Every day. You think I’d have stuck this job so long if I didn’t?’

Sam played agitatedly with his pint glass. ‘It’s crazy, isn’t it? I’ve been going on and on about us two finding the time to sit and talk – and now we’re here, I don’t know how to say what’s on my mind.’

‘The job getting you down?’

‘It’s not the job, Annie. It’s … It’s like … Ach, I don’t know how to put this without sounding like an idiot.’

‘Well, say it anyway. You can’t sound more like an idiot than some people I can think of.’

‘I’ve been dreaming,’ said Sam at last.

‘Oh, aye?’

‘No, not like that. Stupid dreams. I’m always alone. I’m always lost, stuck somewhere I shouldn’t be, unable to get home. Everything’s broken … Like the world’s come to an end and I’m lost, and …’ He shrugged and threw up his hands. ‘I told you I’d make myself sound like an idiot.’

‘These dreams you keep having,’ said Annie, ‘the way they make you feel. Does that feeling stay with you, even when you wake up?’

‘Yes. Yes, it does.’

‘Is it the feeling that you ought to be somewhere else? Somewhere really important?’

‘Yes.’

‘But you don’t know where it is, or why you need to be there. And that feeling doesn’t go away, even when you ignore it and tell yourself it’s just the job or you’re having an off day. It keeps coming back, creeping up on you, all the time.’

Sam leant forward, looking intently into her face. ‘Annie, it’s like you’re reading my mind.’

‘It’s like you’re reading mine, Sam. I know the feeling you’re talking about. I have it too.’

‘You do? Annie, you never said.’

‘Yes I did. Just now.’

‘But … Why didn’t you tell me this before?’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

Sam squeezed her hand, and she squeezed back. He could feel the warmth of her skin, catch the hint of her Yardley perfume, see the light reflecting from her eyes as she looked intently at him. It was a quietly intense moment – a real moment, more real by far than anything he could recall from his old life amid the laptops and iPods, satellite channels and Bluetooths.

‘What does it mean, Annie? Why do we feel like this?’

He could feel it right now, and he supposed that Annie could, too. A restlessness. A deep feeling of a job to do, a train to catch, an appointment to be met, important business to be concluded. Holding Annie’s hand, he looked back across the pub towards the bar. There was Ray, grinning and joking, the empty glasses piling up in front of him; and there was Chris, looking youthful and uncertain as he squirmed from the good-humoured bullying. And, looming over them, there stood Gene – solid, rocklike, wreathed in blue fag smoke that caught the light and glowed all about him like an aura.

But now Sam become acutely aware of Nelson standing just beyond them, pumping bitter into a pint glass and grinning at some inane comment from his CID regulars. Without changing his expression, Nelson glanced slowly up at Sam and Annie; knowingly, he tipped them both a wink.

For a brief moment, Sam felt the sudden conviction that everything here in this crappy, filthy pub was alive with meaning – the bar, the ashtrays, the rings of sticky beer on the tables, and, even more so, the people: Chris and Ray and Gene. Annie too, and Sam himself. And Nelson most of all.

We’re all here for a reason, Sam thought. There’s a plan at work here – and we are all part of it.

And in the next heartbeat, everything faded back into drab normality, the sense of imminent revelation gone. Gene, Ray and Chris were just three mouthy coppers sharing a drink. Nelson was just Nelson. The pub was just yet another reeking Manchester boozer.

‘What’s going on in that noggin of yours, mm?’ Annie asked, leaning closer to him.

‘I was thinking,’ Sam breathed softly. ‘I was thinking that I thought I was here to stay. This place. This life. I thought it was home. But now I’m starting to suspect home’s somewhere else.’

‘Me too,’ murmured Annie.

‘I can’t explain it better than that.’

‘Me neither.’

‘But I do know one thing,’ said Sam, and he looked into Annie’s eyes. ‘Wherever I go, I won’t be able to call it home without y—’

But, before he could say anything more, Ray’s boozy voice cut across them, ‘Look out, lads, it’s Brief En-bloody-counter over there.’

Chris placed a limp hand to his heart, fluttered his eyelids, and gave his best Celia Johnson impression. ‘Oh, dahling, I do so frightfully love you and all that. Merry meh – at once. Oh, do say you’ll merry meh.’

Gene shut him up with a clout to the back of the head, like a headmaster cuffing an unruly schoolboy. For a moment, he seemed unsure why he’d done it – then he turned his back on Sam and Annie and complained to Nelson that he wasn’t drunk enough. Not half drunk enough!

‘Is this a conversation for another day?’ Annie asked, very quietly.

Sam sighed and nodded. The moment was broken. He would have to wait for another.

CHAPTER FOUR

THE PADDY CHAIN

More fag smoke, more unshaven coppers, more testosterone hanging in the air like the scent of musk – but it wasn’t the Railway Arms this time, it was A-Division at Greater Manchester CID. Harsh strip lights burned in the ceiling, casting their unblinking glare over the criminal mugshots and Page 3 pinups Sellotaped over the drab grey walls. Telephones chimed, typewriters clacked, mountainous heaps of paperwork leaned perilously from trays.

Hung over and bleary-eyed, Chris propped himself up at his desk, not even pretending to be fit for work. Across from him, Ray chewed gum and lounged about.

‘Feeling a bit ropy this morning, Chrissie-boy?’

‘I can handle it,’ murmured Chris.

‘Had half a sherbet too many, eh?’

‘I just copped a dirty glass, that’s all.’

Ray grinned and stretched in his chair, flexing his arms and pushing out his chest. ‘Me – I’m laffin’. Fit as a flea. And I matched you drink for drink last night, Chris, which only goes to show …’

‘Lay off, will ya,’ Chris muttered.

‘You gotta learn to manage your drinking,’ Ray went on. ‘You can’t call yourself a bloke, not a real bloke, until you can confidently down it, absorb it, and piss it up a wall like a pro. You think Richard Harris poofs it up like you after a couple of swift ones?’

‘He might do if had my metabolism,’ muttered Chris. ‘Anyway, he’s Irish. I don’t want no mention of anything Irish.’

‘Take my advice, young ’un – stay well within your limits, and leave the heavy stuff to us grown-ups.’

‘I’ll admit it, I might have had one or two more than was good for me,’ said Chris. ‘But I’m a man in trauma. I can’t get that image out of my head – the khazi of doom, all set to blow half a ton of Semtex up me Rotherhithe. It’s haunting me, Ray. Just imagine if that lot had gone off.’

‘You’d’ve ended up feeling no worse than you do right now,’ suggested Ray.

‘God, ain’t that the truth?’ Chris groaned, and slowly sank forward until his ashen forehead rested against his desk.

Without warning, the door to Gene Hunt’s office slammed open, and the guv himself appeared, glaring and brooding like a grizzly bear with a right monk on.

‘DI Tyler, Brenda Bristols, the pleasure of your company, if you please.’

Exchanging looks, Sam and Annie stepped into Gene’s office and shut the door behind them. Gene prowled about behind his desk, not even bothering to conceal the glass of Scotch amid the paperwork. Hair of the dog. His morning pick-me-up. It may be wrecking his liver, but it didn’t seem to be impairing his police work.

‘As you know,’ he intoned, ‘the gunman we so valiantly risked our arses trying to apprehend yesterday managed to elude us. Not only that, he also managed to elude the Keystone Kops outside and their impenetrable “ring of steel”, all of which means I’ve been getting it in the neck from Special Branch for not leaving the operation to them. They’re saying – and I quote – that we made a “right pigging balls-up”. Black mark for A-Division. Black mark for me. And me not well pleased, children, me not well pleased at all.’

He stopped pacing and glowered intensely at Sam for a moment, daring him to come out with an ‘I told you so, Guv’. But Sam knew when to keep it buttoned.

After a few moments, Gene resumed pacing and said, ‘On the plus side, however, our keen cub reporter Annie Cartwright has supplied us with a useful lead. Go on, luv, tell us what you got.’

On cue, Annie produced some typewritten pages and read from them: ‘Michael and Cait Deery. Husband and wife. Irish nationals residing somewhere in Manchester. There’s been a Home Office file on them for months now. It seems pretty certain they’re acting as couriers between Ireland and the mainland, shipping in firearms, ammunition and plastic explosives to supply IRA cells.’

‘If the Home Office know about them, why haven’t they been arrested?’ asked Sam.

‘Because they’re more valuable left alone to do their thing,’ said Gene. ‘The contacts they meet, the people they deal with. It might all just reveal the whole chain, connecting bomb factories in Dublin to attacks being planned on the mainland.’

‘How sure are we that they were anything to do with what happened at the council records office?’

‘For want of anything better to go on I’m working on the assumption that the Deerys are involved,’ said Gene. ‘If there’s an IRA unit at work on our patch, we’ll find it through them. And bagging an IRA unit might just make up for yesterday’s fiasco. Um, excuse me, DI Tyler, but did somebody drop the marmalade in your pants this morning? What’s that gormless face for?’

‘You’re working on the assumption that what happened yesterday was the work of the IRA,’ said Sam.

Gene sighed. ‘Oh, God, Sam, not this Old Mother ’Ubbard again!’

‘I know you’re resistant to my line of reasoning …’

‘To put it poncily.’

‘But I’m telling you, Guv, we’re going to find out sooner or later that what kicked off yesterday had precious little to do with the IRA.’

‘A bomb, a bloke in a balaclava and a certain negativity expressed towards the British constabulary – now, I’m the first to admit I’m not Sherlock bloody Holmes, but—’

‘I’ve already told you, Guv, I’m not convinced,’ said Sam. ‘That bomb in the toilet – it was a message of some kind. It meant something. It was more symbolic than a genuine threat.’

‘Unlike this,’ snapped Gene, raising a balled fist in front of Sam’s face.