Полная версия

Sitting Up With the Dead: A Storied Journey Through the American South

Copyright

The author and the publishers of this work would like to express their gratitude to the following: Louisiana State University Press for permission to quote from Black Shawl by Kathryn Stripling Byer (Copyright © 1998 by Kathryn Stripling Byer); Copper Canyon Press for permission to quote from Deepstep Come Shining by CD. Wright; Vintage Press for permission to quote from North Toward Home by Willie Morris; J.M. Dent and Sons for permission to quote from ‘Eheu Fugaces’ from Collected Poems 1945–1990 by R.S. Thomas; and Universal Music Publishing Ltd for kind permission to quote lyrics from ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ (King/Vanzant/Rossington). Although we have tried to trace and contact all copyright holders before publication this has not been possible in every case. If notified, the publisher will be pleased to make any necessary emendations at the earliest opportunity.

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Fourth Estate is a registered trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Limited

First published by Flamingo 2001

Copyright © Pamela Petro 2001

Copyright disclaimer: All of the material printed in optima retains the copyright of the storytellers featured in this book.

Pamela Petro asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007292295

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007391073

Version: 2016-02-17

Dedication

For Marguerite Itamar Harrison,

who introduced me to the American South

and the Southern Hemisphere.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

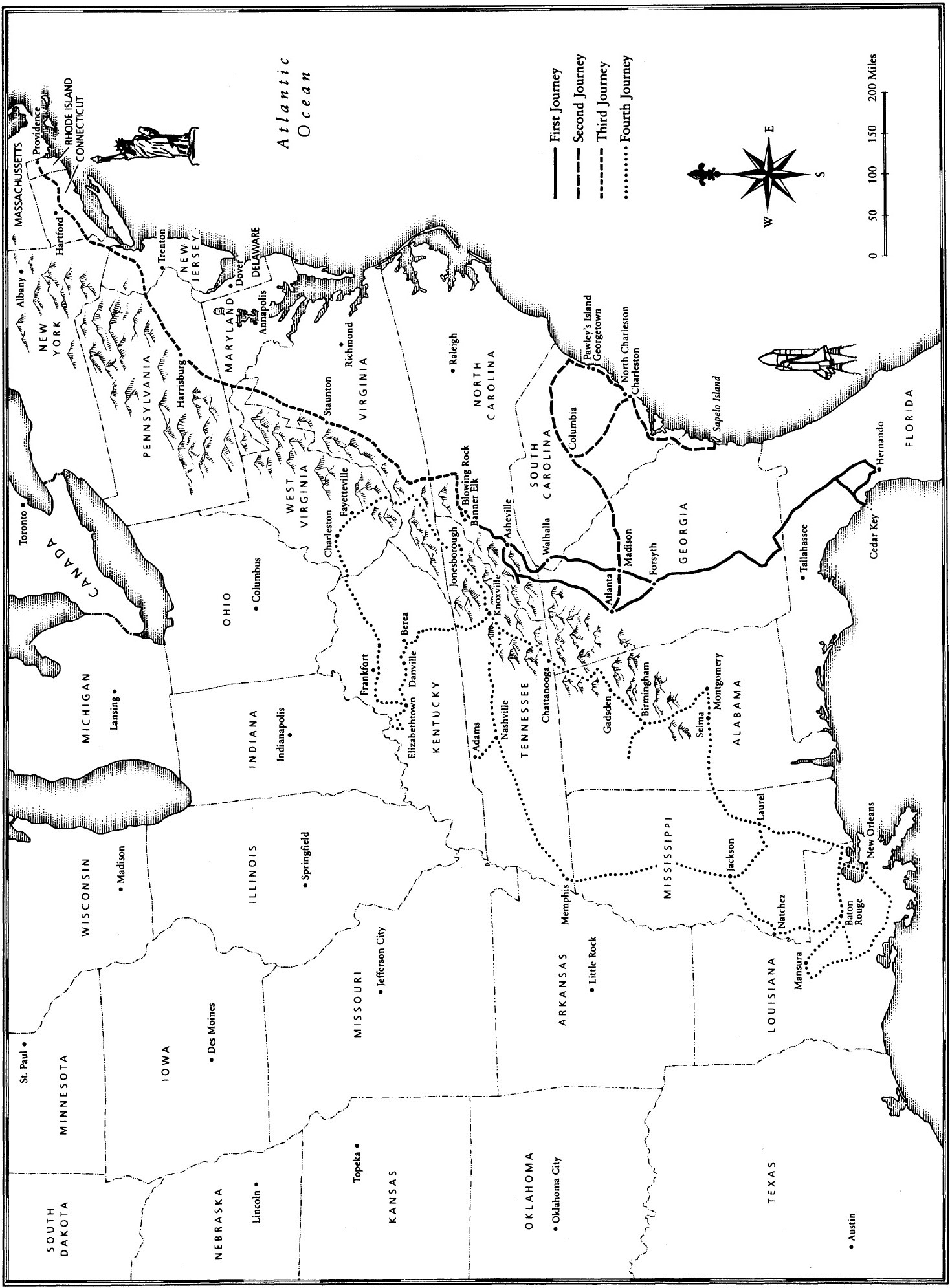

Map of the American South

The Prologue

JOURNEY 1

AKBAR’S TALE

Tar Baby

COLONEL ROD’S TALE

The Mule Egg

VICKIE’S TALE

ROSEHILL’S TALE

The KUDZU’S TALE

Grandfather Creates Snake

ORVILLE’S TALE

Jack and the Varmints

DAVID’S TALE

Ross and Anna

JOURNEY 2

VERONICA’S TALE

A Polar Bear’s Bar-be-cue

Taily Po

KWAME’S TALE

The Story of the Girl and the Fish

ALICE’S TALE

CORNELIA’S TALE

The Plat-eye

FOUCHENA’S TALE

The Flying Africans

MINERVA’S TALE

TOM’S TALE

The Story of Lavinia Fisher

JOURNEY 3

RAY’S TALE

JOURNEY 4

OLLIE’S TALE

KATHRYN’S TALE

The Grandfather Tales

DAVID JOE’S TALE

The Peddler Man

KAREN’S TALE

Rosie and Charlie

The Tale of the Farmer’s Smart Daughter

OYO’S TALE

MITCH AND CARLA’S TALE

How My Grandma was Marked

Wicked John

The Bell Witch’s Tale

ANNIE’S TALE

Shug

My First Experience with a Flush Commode

ANGELA’S TALE

ROSE ANNE’S TALE

The Song In The Mist

Granny Griffin’s Tale

The Dead Man

Keep Reading

Index of Stories/Storytellers

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map of the American South

‘In America, perhaps more than any other country, and in the South, perhaps more than any other region, we go back to our dreams and memories, hoping it remains what it was on a lazy, still summer’s day twenty years ago – and yet our sense of it is forever violated by others who see it, not as home, but as the dark side of hell.’

WILLIE MORRIS, North Toward Home

The Prologue

Chaucer said it was in April that people long to go on pilgrimages. I was two months late; the desire didn’t come upon me until June. His Canterbury-bound pilgrims were moved ‘to seek the stranger strands/Of far-off saints, hallowed in sundry lands.’ A nice idea, but again, my journey differed in the details. No sundry lands for me. Like a contented lodger taken in by a big, unruly family, I lingered in just one place, or one household, you might say, within the United States: the American South. And I wasn’t seeking saints.

What Chaucer’s pilgrims and I have in common is that we chose stories as our waymarks. I traveled from the Atlantic seaboard across the high country of Appalachia to the Gulf Coast, listening to Southern storytellers tell me their tales. Like the Knight, the Nun and the Wife of Bath, stories served all of us – listeners and tellers alike – as compasses of understanding to high country and low, to the past and present, to ghosts and the living, to right, wrong, and finally, to the way home. Chaucer knew that stories are the surest guides on any journey. They are, in fact, journeys themselves, leading out of the graspable, sweaty present into the vanished or imaginary worlds that support it. They give depth and shading to the here and now, comment on it, contradict it, and crosshatch all that we think we know about a particular place with the shadows of lives long gone and schemes of characters who never actually breathed, but flourish in communal daydreams.

Visit the old coal-mining region of eastern Kentucky these days and you’ll see the green hills roll by like a bright, inland sea, buoying up Interstate 64 and the service industries moved down from the Northeast to take advantage of lower taxes. Then find someone with a minute or two to spare, and ask him to tell you a local tale. Maybe over a cup of coffee, or lunch of tinned fruit and cottage cheese at a diner, he’ll spin out The Black Dog, which is about a coal-mine collapse and the heroic pet who protected his master even in death. It’s a tale about community and the fear of outsiders, even outsiders offering help; about trust and the habitual acceptance of death and the forgotten bond between men and animals. This is the heritage of the upland, coal-mining South, and it’s invisible to the eye. But stories like The Black Dog are able to unearth an older Kentucky, one that still has relevance because it lives in the memories of service industry employees who drive to work on the Interstate, even though it may no longer be reflected in their daily landscapes. Travelers can’t see it, but they can hear it if they listen.

Stories provide the connective tissues of a community, a region, or even a big, overgrown household like the South. They link the skin of the present to the unseen organs of the past, binding them into a continually shapeshifting body by turns beautiful and terrible and occasionally – disturbingly – oddly reminiscent of looking into a mirror. In my case, the glass reveals a surprise: a Northern woman, a Yankee who came of age in Britain, and now lives within the gravitational pull of Boston, Massachusetts – the geographic butt of nearly every dumb joke I heard in the South (‘Hey,’ the Texaco cashier would say, as I paid for the gas I’d just pumped, ‘hear the one about the guy from Boston who bought his girlfriend a mink coat?’ Or, ‘There was this guy from Boston with a chicken …’ in which case I’d affect a Southern accent and say I was from Virginia). It’s a fair question to ask what I was doing there.

Tony Horowitz wrote in Confederates in the Attic that, ‘The South is a place. East, West, and North are nothing but directions.’ When I read that my kneejerk reaction was to agree; I couldn’t explain why, but I wanted to find out. In my previous book, a journey round the world in search of Welsh expatriates – a group for the most part anchored by a concrete sense of identity – I had written of myself, by way of contrast, ‘To be an American, I sometimes feel, is to be blank, without a nationality or language.’ It was easy for me to write that sentence. I grew up in the suburban New York area, the heartland of the American communications industry that daily beams a facsimile of itself to the world. To be Northern, for me, is simply to be American. But Southerners – at least those in print – seemed to feel very differently, branded on the soul by the geography of their birth. Why? What place-bond did they have that I didn’t? In North Toward Home, Willie Morris, a Southerner from Mississippi, wrote of himself, ‘The child … was born into certain traditions. The South was one, the old, impoverished, whipped-down South; the Lord Almighty was another; … the Negro doctor coming around back was another; the printed word; the spoken word; and all these more or less involved with doom and lost causes, and close to the Lord’s earth.’ I had no such waymarks, and however fraught the Southern identity might be, I yearned for such a bond.

Growing up in the Sixties I had learned that the South was a scary place. Whenever I tried to conjure images of the things I knew to be there – tobacco fields, sharecroppers’ shacks, flat-roofed stores on Main Streets and old-fashioned buses – I saw them in my mind’s eye through an eerie blue light. These Gothic stage sets of mine had origin in a mundane reality: the fact that most of my childhood impressions were thrown into our safe, Northern living room by my parents’ black and white television set. Unfortunately, they were usually disturbing: blurred scenes of race riots and fierce men with firehoses, dogs attacking crowds of protesters and marchers in pointy hats and white sheets. It didn’t help that the picture used to roll a lot (usually set right by a whack on the side), making the images even stranger. The South looked like the site of a haunting: a dream world, not a waking one.

I was a dramatic child, given to extravagant musings – usually involving hauntings closer to home, principally in my closet – and eventually outgrew most of my darker impressions. But scratch the surface of nearly all Yankees and there remains a prejudice against the South – an unvoiced, but understood, moral superiority. We won the Civil War because we were right. ‘Be careful down there.’ I heard that advice from more than a few Boston friends. ‘Will you be safe alone?’ ‘You know, it’s still pretty rural down there. All kinds of things go on.’

Down There. The South has always been somewhere below my home. I have a strange semantic prejudice, probably endemic to the Northern Hemisphere, that North is ‘up’ and South is ‘down’. So to go down there was to descend geographically. And in many ways, I discovered that it was also to descend metaphorically, Orpheus-style, not so much into the Underworld as a kind of national Otherworld, an ornery, land-wedded, once-and-future counterbalance to the here-and-now America of my experience, the latter made generic through self-promotion. In much of the world’s oral literature – the old stories explaining the external world that lived through a spoken chain of memory – travelers went to the Otherworld because theirs was missing something, usually some critical means of reproducing itself (hence the ceaseless abduction of magic women in Celtic lore). They were thieves, to put it bluntly, but their plunder usually saved the day.

In my case, I was missing two things: a sense of my country as a place, not simply a well-oiled machine ceaselessly turning out the future, and, on a personal level, a voice. I am a relentless daydreamer. I tell myself tales so intricate and involved that they blot out whole days of my life. Like storytelling, like travel, like madness and violence, daydreams lead out of the known world into exceptional places – some of which no one in his or her right mind wants to visit, others wondrous and wise. But unlike those other means of transportation, daydreaming is a solitary sport in which stories are hoarded rather than shared. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard asked, ‘What is the source of our first suffering?’ only to answer himself : ‘It lies in the fact that we hesitated to speak. It was born in the moment when we accumulated silent things within us.’

Who better than tellers – people whose role it is to share stories – to help me make a personal voyage from silence to speech (or in my case to writing, which is little more than speech’s shadow), and thereby ditch my accumulation of fictional silence? So I went down into the Otherworld of the American South and I came back with stories. With living, listened-to tales that would be my exemplars, and that also might help me understand the open-ended, unfinished place that Civil War historian Shelby Foote says gives us ‘a sense of tragedy which the rest of the nation lacks’ – not to mention why my sense of America is incomplete without it.

I should note that I opted to plunder spoken stories, as opposed to written ones, because they are chosen for their listeners, not by them, as is the case with readers. It was better, I thought, to have my assumptions made for me by Southern storytellers than to make my own, loaded as my selections would be with outsider’s baggage. I asked each teller for a story or a tale that revealed something of the nature of life in his or her corner of the American South. (These semantics mattered, as the word ‘story’ often invokes the private realm and ‘tale’ the public; this option left tellers free to choose the space in which they felt the most comfortable, or thought was the best cipher of the South). The orality of the stories was important as well. Oral tales are a plural endeavor; they’re the products of generations and geography and weather and all the other ligaments that bind a community together. Written stories, by contrast, are idiosyncratic and individual, and it was a public sense of the South I sought, not a private one. Besides, two covers, a spine, and a few hundred pages don’t have nearly as much personality as living, cussing, dancing, spitting, smoking, eating, drinking humans. Storytellers are often their own stories. They certainly became mine.

First Journey

R.S. THOMAS, ‘Eheu Fugaces’

Between

One story and another

What difference but in the telling

Of it?

Akbar’s Tale

I WAS WEDGED INTO THE AISLE OF THE PLANE, waiting impatiently to exit, when a fellow passenger whispered uncomfortably close to my ear, ‘They say that when you die, you have to change planes in Atlanta to get to heaven.’

Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport is the second-busiest in the United States. Although it looks like every other airport in the world, the talk there is exceptional. As soon as I arrived in the main terminal, a short, squarish security woman called me ‘baby’, which I found unaccountably comforting (as in ‘You lost, baby’, after I’d attempted to retrieve my luggage from the wrong baggage carousel; my suitcase was doing figure-of-eights on another conveyor belt on the far side of the airport). A few minutes later a very tall African-American man questioned me about cigarettes in Japanese. When I looked confused he switched with great courtesy to chewy-vowelled, Georgia English.

The South is a famously talky place. The quintessential Southerner, William Faulkner, wrote, ‘We have never got and probably will never get anywhere with music or the plastic forms. We need to talk, to tell, since oratory is our heritage …’ Even bones talk sometimes. Even when they’re in the ground. There is a story from the South Carolina coast called The Three Pears, or The Singing Bones, about a little girl who exasperates her mother by eating pears meant for a pie. Understandably peeved, the mother chops the girl up with an axe and buries the pieces around the farmyard. The head is packed off to the onion patch, which next spring bears a ‘fine mess’ of onions. Sent to pick them, the son hears the ground singing:

Brother, Brother, Brother

Don’t pull me hair

Know mama de kill me

Bout the three li’ pear

Eventually her bones testify to everyone in the family, and the mother gets so frightened she runs into a tree and dies.

When I first encountered this story I thought, imagine what a ruckus a Southern cemetery would kick up. So many bones prattling on about this and that, that you wouldn’t be able to hear yourself think. Strangely, this old rural tale is what surfaced in my mind as I was swept out of the Atlanta airport in my new rental car, into a twelve-lane funnel of life moving at top speed. ‘Such a metaphor,’ I scribbled on a note pad, risking annihilation as truckers passed me at 80 mph, and Highways 75 and 85 blurred together in a whirlpool of relentless motion. Atlanta is a city on the move, shamelessly advertising America’s infatuation with roads and size and moneymaking right in its freeway-bound heart. No time for death here, much less quaint talking bones. If there were any, I felt sorry for them: no one would be able to hear their chants in the din.

Actually, that is not quite true. Atlanta discovered some of its own old bones a few decades ago, and they shout their message – ‘Make Money!’ – loud and clear, which is probably why the story came to mind in the first place. In the center of the city is a four-block grotto of unearthed, nineteenth-century cobblestones called Underground Atlanta, excavated and rebuilt as a tourist mecca of glitzy shops and restaurants. These skeletal streets were the foundations of the original city, begun in 1837 and first called Terminus, appropriately enough, for the railroad speculation venture that it was. The district wasn’t burned by General Sherman’s Union troops in the Civil War; it was buried to make way for a railway aqueduct. What began as a commercial venture died as one, only to be resurrected over a century later on behalf of yet another kind of commerce. It is the Atlanta way.

Those who don’t hear the call of money beneath the city chase it toward the sky. Office and shopping towers sprout in clusters throughout the metropolitan area like so many galvanized steel ladders to the future (getting from one to another means that Atlanta residents spend more time commuting in cars than any other Americans, each logging around thirty-five miles a day). It is no accident that Tom Wolfe’s recent novel, A Man in Full, hinged on the fortunes of a reckless Atlanta speculator who built a skyscraper too high for his wallet. Not so much fiction as parable, Wolfe’s story of success-run-rampant tells the tale of the city’s recent history. In the 1990s metropolitan Atlanta saw the greatest population increase in America. It currently consumes fifty acres of forest land per day to pave way for new construction. The city is, in fact, the epicenter of an economic boom so great that if the eleven states of the former Confederacy were lumped together as a separate nation, they could claim the fifth largest economy in the world (equivalent, so I’m told, to Brazil).

This is the ‘New South’ that so many speak of: socially liberal and friendly to big business – an attractive combination paid for in road congestion, air pollution, and overdevelopment. Yet Atlanta was on the make long before CNN, Coca-Cola, and the 1996 Olympics arrived. It has always been what some are complaining it has now become: a work-ethic driven, live-and-die-by-the-dollar, Northern kind of city, noisy and fast and flush with money.

Atlanta was the first stop on my first trip to the South. Over the course of the summer I planned four separate journeys, with brief rest stops at home in New England in between. I knew that my travels would generously overlap themselves and one another: because I was using storytellers rather than states or cities as my coordinates, I expected to leave a messy trail on the map, but gather a rich earful en route. On this first trip I took Georgia for my base, with forays planned both north and south of the state. The other journeys would take in the eastern seaboard, Appalachia, and ‘the Deep South,’ which included Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. More immediately, however, navigating Atlanta was my chief concern.

None of the people behind the desk at the Super 8 Motel in the heart of downtown had ever heard of Ralph David Abernathy Jr. Boulevard, which disturbed me. Abernathy was Martin Luther King Jr.’s right-hand man throughout the Civil Rights Movement. While nearly every town in the South with more than one stop sign has an Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, or at least an Avenue, most of the major cities have named something after Abernathy too, and it’s usually a pretty significant street. Atlanta is no exception, but it took two painters suspended on scaffolding in the motel lobby to shout directions down.

‘No one’s ever asked for Abernathy before,’ said one of the clerks.

I soon discovered why. Abernathy proved a conduit to Atlanta’s West End, an old African-American neighborhood of bungalows with sagging porches, pawn shops, fast-food restaurants, and corner stores hidden behind anti-theft grills. Conversational half-circles of chairs were set up here and there on the sidewalks but were all empty: already at 10 am steamy, near-tropical heat had a stranglehold on the day. Here, at last, was a restful nook in the city – a little ramshackle, but pleasantly quiet. I was no longer surprised it had been so hard to find: this neighborhood was the Atlanta anomaly, more Old South than New, where time was to be had in greater quantities than money.

All the bigger buildings seemed boarded-up, except one. Marooned on the shabby street was a well-kept monument to Victorian whimsy: a many-gabled Queen Anne-style cottage with yellow patterned shingles, tall chimneys, and a giddy wraparound porch that looked like a carnival train of painted wagons. This was the Wren’s Nest, former home of Joel Chandler Harris, the nineteenth-century newspaper man who gave the world Uncle Remus, and wrote down the Brer Rabbit stories.

I made my way onto the tangled grounds and a teenager named Matthew ran up and shook my hand. He lived nearby and was a summer intern at the house, now a museum. We traded confessions of childhood fears. He’d been afraid of hockey masks because the killer in Friday the Thirteenth had worn one; I’d thought pink paint could only be achieved by mixing white paint with blood, and one day insisted (on pain of sleeping elsewhere) that my room be painted blue. After these confessions we were buddies, and he showed me around the musty Victoriana: a full set of Gibbon in the library, windows shuttered against summer heat, tasseled lamps lit in the gloom, and 31 five-year-olds racing up and down the long, ‘dog trot’ hallway, the electric heels of their Nike sneakers flashing red. The five-year-olds and I had come to listen to Akbar Imhotep, a storyteller who had not yet arrived. While I waited for Akbar, I watched a slide show about Harris’ life, slightly unnerved that the rest of the audience consisted of a stuffed bear and rabbit – both dressed for church – and a fox in need of a taxidermist’s touch-up.