Полная версия

Ting Tang Tommy

The Scissors Game

This game works best with plenty of people. Everyone sits in a circle, and only a small number (ideally no more than two) should know the rules of the game. A pair of scissors is passed around and around the circle. Each time you pass it to the person next to you, you have to say ‘I PASS THE SCISSORS CROSSED’ or ‘I PASS THE SCISSORS UNCROSSED’. The recipient has to say ‘I RECEIVE THE SCISSORS CROSSED’ or ‘I RECEIVE THE SCISSORS UNCROSSED’. The people who don’t know the rules will begin by assuming that the words relate to the state of the scissors and whether the blades are open or not, and the people who know the rules can take advantage of this. Actually, each statement refers to whether the players who are passing and receiving the scissors have their LEGS crossed or uncrossed. As you go around the circle, as people make statements that are false they lose a life. Three lives lost and they’re out. People become more and more frustrated but eventually they begin to cotton on to the rules and subtly try and keep the people who don’t understand from working them out. When all the players left in the circle get it, the game is over and everyone can have another drink.

Word Tennis

The school was one big studio in which all the classes took place. At the back of the room, on a raised platform, sat three washing baskets filled with props and costumes, a bus stop sign and a small record player. Every week I would enter, pay my pound for the class and sit quietly at one side of the room. There would be little talking, just an atmosphere of silent expectancy as we waited for the arrival of Anna. Everyone would sit, carefully scanning each other.

There were sixty of us in a class. Kids came from all over London but especially from the areas nearby—King’s Cross, Islington and Highbury. These were not privileged stage school types, but local working-class kids who loved acting. There was no audition or interview, just a four-year waiting list. When your name came up you would start the following week.

The school was like a boxing club. You went there and for two hours you improvised the most intense, unflinching scenes you could. Domestic violence, drugs, alcoholism and broken families all featured heavily. For the first six months I was practically silent. I felt nervous and confused. Acting had always been about scripts. Doing a play involved being given a part, learning my lines and then performing on the night. But in this world spontaneity was everything. With your partner you would be given a first line (‘That was bang out of order!’, ‘You do nothing round the house!’, ‘I’ve had it up to here with you!’) and, in front of everyone, you would have to improvise a situation. There was no time for throat clearing—bang, you were in the scene. And the style was direct, confrontational and fast. The scenes rocketed up the emotional scale as you let rip on your colleague. This training taught me a lot about how to play games. My eight years at Anna’s taught me that thinking on your feet and embracing the unexpected is the place where creativity begins.

Some weeks, if the class had been particularly intense, we would end with a game. The one I enjoyed most was Word Tennis. Since learning the game at Anna’s I’ve played it in many different contexts. It can be played standing up in a line or sitting down and children and grannies love it. It’s called Word Tennis because the aim is to keep the word rally going for as long as possible.

Everyone sits in a circle, either on chairs or round a table. Someone starts by suggesting a category with lots of members, for example, Sports. The person gives an example of the category (football) and the game begins. Travelling in a clockwise direction, each person must give an example from that category. If it’s Sports, people might say basketball, hockey, or tennis. You keep going until someone hesitates, repeats a name or can’t think of another one. After a few trial runs you can start eliminating people. When someone is out you start again with a new category. If you have been playing sitting down, when you get to the last four people still in, ask them to stand up. This increases the stakes. You keep going until only two people are left in. Everyone suggests categories for the final and you have a dramatic showdown.

Fun categories really help. Here are some you might like to try:

Sweets and Chocolates Fairytale Characters Things that Live Under the Sea Five-Letter Words Types of Footwear Fairground Rides Things People Do to Keep Warm Three-Letter Words Things You Might Find in a Convent Precious Stones Things People Do When They’re in Love Horror Films Dwellings Fashion Designers Things that Cost Under £1 Sandwich Fillings High-Street Stores Objects with Doors Contents of a Lady’s Handbag PoliticiansEmpire

Everyone writes the name of a famous person down on a scrap of paper. They then fold up their bits of paper and throw them into a hat. The umpire also writes a name on a piece of paper and adds it to the hat. This name will be known as the Wild Card.

The umpire takes the names out of the hat and reads them aloud to the group twice through, explaining to the group that they must remember as many names as possible. The names are now put back into the hat, which is placed to one side. The umpire then selects a player to start. This player must try and guess which player has written which name. They might start by suggesting that their bookish elder brother is Paul Auster, or their trendy younger sister Vivienne Westwood. If this player guesses correctly then the person whose name they have guessed must join their empire. They may confer with their new recruit to keep remembering names and guessing who wrote them. If they keep guessing correctly, their empire expands accordingly.

If a player guesses wrongly, the turn passes to this player whose name hasn’t been guessed. They take over and begin to guess names. If they manage to guess the name of a person who has already accrued an empire, this person and all her captured players move to this new emperor. The game ends when one person has subsumed everyone into one huge domain. The aim is to remember all the names and to match them all accurately to their source.

The first time you play this, you might want to ask every-one just to write down names without telling them what is to come. People will write names that clearly reflect their interests and tastes. They will be easy to guess. You will play the first round and people will be a little non-plussed. Then, having played the game, ask everyone to disguise themselves by writing a name no one would expect. So the young proto-feminist in the group might write Jeremy Clarkson, the bookish elder brother Sporty Spice and the mild-mannered granny Sid Vicious. This time the game takes longer and becomes fascinating as everyone tries to guess who is behind each name. The names act like masks. Crucial to the game’s success is the Wild Card. The status of the Wild Card cannot be established definitively since the umpire who wrote it cannot be questioned. Empires have to establish for themselves which name is the red herring.

The aim of the game is world domination. So what’s new?

Cheeky Golf

You need a fifty pence piece and a pint glass. Establish a line a few metres from the glass and ask a volunteer to stand behind it. The player then takes the fifty pence piece and clenches it between his buttocks. Keeping hold of the coin, the player then attempts to walk forward before successfully releasing it into the glass. Players can either drop the coin from a height or try and squat over the glass. Although the idea may strike the assembled company as too awful for words, it’s actually very straightforward. Our muscles in this area are strong and carrying a coin around is actually pretty easy. There is also the most remarkable joy in hearing the tinkle of the coin landing in the glass: it’s probably the nearest we’ll come to the satisfying pleasure of laying an egg.

If you have the appetite to go further, you can think about creating an obstacle course between you and the pint glass, using chairs and other bits of furniture.

The Cereal Game

The aim of this game is to pick up the cereal box using your teeth, with only your feet touching the ground.

Place the cereal box in the centre of the circle, far away from any coffee tables or furniture. Go around the circle, with everyone having a go. Most people will manage to bend over and lift the box into the air using their teeth without too many problems. Next, using a pair of scissors cut off a strip around the top of the box, so that it’s something like a fifth lower. Now, go round again, remembering that if any part of the body—apart from the feet—makes contact with the ground the person goes out. This includes players losing their balance. Keep going for about five rounds, with the packet being cut down lower and lower each time. More and more people will go out until you are left with your finalists. If the remaining individuals are demonstrating a rare expertise, then for your very final round you can cut off the lip of the packet entirely so that players have to suck the horizontal piece of card off the floor while essentially being upside down.

I have seen it done.

Clap Volleyball

We had decided to tour The Winter’s Tale, with a cast of ten and minimal props. Even with no scenery, transporting cast and equipment became a major headache. Trains were cumbersome and journeys time-consuming. We only had a month during our holidays and Charles was determined that we made all our dates. I was becoming more and more anxious but Charles reassured me that he would find a way and that I should simply concentrate on casting and rehearsing the show.

On the first day of the tour we gathered outside the Maypole pub in Cambridge to find one large coach and two rather confused-looking drivers. The plan was simple. We were to climb aboard and then drive, via Berlin, to Moscow for our first performance. From there we would drive across the former Soviet bloc, criss-crossing countries to deliver our pared-down version of Shakespeare. And so began a remarkable month of eleven overnight journeys, bus drivers being taken to the verge of madness, passionate love affairs, late-night border inspections and unending streams of vodka.

Somehow we made it on time for our first performance in Moscow. The show went well and the cast and I were invited to attend a workshop at the Moscow State University, given by a director and expert in the Stanislavski Method. We expected two hours of rigorous emotional exercises. What we got was a lot of clapping. The director explained how awareness, contact and speed were at the heart of his approach to theatre. And so he taught us this simple but potent game, which I have played in practically every rehearsal room I have been in since. It works with friends, too. You need a big space, but the joy is that, although it’s a kind of volleyball, you can play it indoors since there is no ball to break anything with…

You need a minimum of seven players: two teams of three plus one umpire. Begin by asking the teams to choose names, and then get them to stand opposite each other in two lines. Just as in real volleyball, appoint someone on Team A to serve. Their job will be to make clear eye contact with someone on Team B and fire the clap to them. Without hesitation, this player must send the clap back to someone else on Team A and so a rally begins. Teams drop points by indirect clap throwing. Equally, if the clap is clearly aimed at someone but they are dozing and there is a split-second lull, the other team gains a point. The aim is to create fast and furious rallies that last until concentration reaches breaking point.

Smashes are allowed, but they carry risks. Rather than directing the clap straight to the opposite team, players may pass the clap down the line to someone on their own side. However, if this person is distracted and hesitates then the other team wins a point. The clap may be passed along a team as many times as players wish, but everyone must maintain their position in the line and any hesitation must be leaped on and penalized by the umpire. The first team to score five points wins.

When I’m the umpire I build tension by winding up both teams as much as possible to win. When you’ve appointed a player to serve, tell them to wait for a visual cue. This gives everyone a chance to regain their focus. Position yourself between the lines at one end and begin by crying, ‘Let’s play Clap Volleyball!’

Mickey Mouse

Touched by my overpowering enthusiasm (if nothing else), the theatre decided to commission the play and so began a two-year process of writing and workshops to develop a new work—Mister Heracles—based on Euripides’ original.

The plot of the play was profoundly serious. The drama tells the story of a triumphant Heracles returning home after the completion of his labours only to suffer a breakdown and murder his wife and children. During rehearsals it was easy to become sucked into the play’s darkness and, to keep our spirits up, we played games. In order to work, these needed to be as silly and lively as possible. One of the actors in the cast taught us this game, which fitted the bill perfectly.

This game doesn’t need many players to work. Playing with a small number of people is actually better as you have to be on your toes even more than usual.

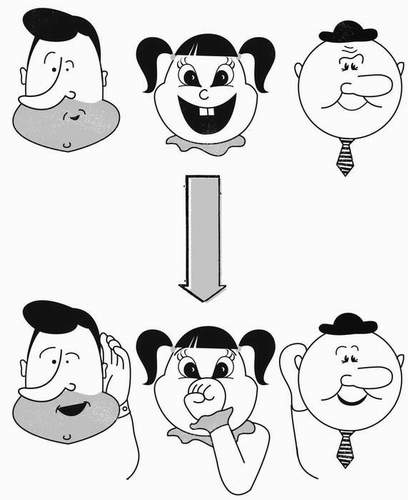

Everyone stands in a circle. The player who starts covers his nose with his fist to make a Mickey Mouse nose. The player to his right places his left hand behind his left ear to make a Mickey Mouse ear. The player to the left places his hand behind his right ear to make a Mickey Mouse ear on the other side. So you now have a nose and two ears made by three different players. The player with the nose now throws it across the circle to another player who ‘catches’ it. That person now has the Mickey Mouse nose and the two players either side of him must make the ears on the correct sides.

The nose is now ‘thrown’ faster and faster around the circle. You will find that people consistently forget to make the ears at the right time on the right side. Keep going until the nose is constantly moving, with hands moving from ears to noses to ears. The aim is to heighten everyone’s awareness of what is happening and to develop fast, intuitive reactions.

You can introduce a competitive edge by eliminating people who make a mistake. Or you can just play for the fun of it—enjoying the swirl of ears and noses. Some years later, I saw one of the actors at a crowded opening night in a theatre in London. Across the crowded stalls he ‘threw me a nose’.

Chinese Pictures

This game is a variant on the Consequences model, which I discuss in Chapter 4. The origins of this game are hinted at in a book called Kate Greenaway’s Book of Games from 1889. Here one player draws a famous scene from history or fiction and the other players have to write down what they think it is, before folding their suggestion over and passing their paper on. At the end players unfold their papers and read out a list of possible definitions. But this version, where everyone is constantly drawing and writing, is a lot more fun.

Everyone begins with a pile of papers, each about the size of a quarter of a piece of A4. It’s crucial that you begin with the right number of papers. For an odd number of players you’ll need the same number of papers; for an even number of players you will need one less. So for nine players you’ll need nine papers, for eight you’ll need seven. On their first piece of paper everyone writes down a film title. Now everyone passes their entire pile, with the title still on top, to the person on their left. This player looks at the title and places it at the bottom of the pile. Now they must attempt to draw the film title on this new piece of paper. They can do this either by breaking down the title of the film or by drawing an image that communicates its essential content. When this is done, players pass the entire pile to the player on their left. This person looks carefully at the picture and then puts it to the bottom of the pile and on the next new piece of paper writes down the title that it suggests to them. When they have done this they pass their entire pile to the person on their left, who reads the title, places it on the bottom and draws the picture that expresses it. It’s essential that the entire pile is passed on each time and this process of reading/writing/ drawing continues until people get their original title back.

After they have been reunited with their original title, each player now reveals their sequence of words and pictures. Players talk through their sequence, holding up one paper at a time. A potential example might go: I wrote down One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Dad drew [show strange drawing of a flying bird]; Granny wrote Chicken Run, Mum drew [an abstract figure distantly related to a chicken fleeing a prison] and Grandpa wrote The Fugitive, and so on.

It’s fantastically rewarding when one series of papers manages to successfully convey one consistent title, but this is pretty rare. There is no winner; the pleasure lies in the often crazy relationship between image and title. Players should do their best to be as precise and detailed as possible but more often than not this is a celebration of distortion. Also, don’t be put off by people being confused or grudging at the start. The game reveals its magic gradually and it’s always thrilling to discover the way you arrive back at your title and the mad journeys everyone has gone on.