Полная версия

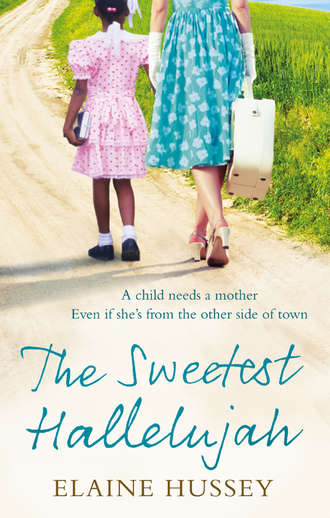

The Sweetest Hallelujah

Joe used to say she could live at The Bugle, and it was true. She loved the clatter of the presses and the smell of ink. Cassie settled Joe’s plaque on the corner of her desk and her coffee cup on a ceramic trivet painted with rainbows. Give Your Soul a Bubble Bath, it proclaimed.

Searching her phone book for the number, Cassie dialed Betty Jewel Hughes.

“Hello.” The woman at the other end of the line spoke with dark, honeyed tones that made you want to sit outside in the sunshine and listen to the universe.

It turned out the woman was not Betty Jewel, but her mother, Queen Dupree. Her daughter, she said, wouldn’t be home till late that afternoon. Though Queen sounded both ancient and anxious, she finally agreed for Cassie to come to Maple Street.

Cassie glanced at her calendar. “I’ll be there today at five.”

A dying woman doesn’t have any time to lose.

Seven

SITTING IN THE PASSENGER side of Sudie’s old car, Betty Jewel wondered if it was possible that miracles are not prayers answered but the answer to prayers you didn’t even know you should pray. Maybe she should have left off praying for a cure for cancer and the freedom for her daughter to walk into the Lyric theater downtown and sit anywhere she pleased. Maybe she should have been praying that her life would be ordinary. Wake up, cook breakfast, plant your collard greens and watch your child grow up. The things millions of women took for granted.

She had been on the front porch swing, wrapped in one of her mama’s quilts and sick from her soles to her scalp, when Sudie’s ten-year-old Studebaker with most of the black paint missing had chugged to a stop in front of her house. Out stepped Merry Lynn wearing a pink hibiscus-print swimsuit—Esther Williams, except colored. Sudie came around the car, her sprigged-green-print skirt swinging as she walked, and her bosom, large for a woman her size, supported by enough black latex to cover a barge.

“Grab your suit, Betty Jewel,” Sudie had said. “We’re going to the old swimming hole.”

“I can barely walk, let alone swim.”

“Sudie took the day off, and don’t you dare try to say no.” Merry Lynn marched onto the front porch with Sudie where the two of them made a packsaddle of their crossed arms and joined hands. “Hop on.”

“I can walk.”

“Not today, you don’t,” Sudie said. “Get on, Betty Jewel.”

“I’m not doing a thing till you promise I won’t hear any talk of finding a cure in Memphis.”

“I promise and so does Merry Lynn, though I can tell by that stubborn look she won’t say so. Now, get your butt in gear and get on this packsaddle before I put it in gear for you.”

She climbed aboard her not-too-steady seat and they hauled her off to the car, thankfully before she toppled off and added broken bones to her list of troubles. Merry Lynn raced back into the house, then returned with a quilt and her blue swimsuit, the one Betty had bought in Memphis the year she’d married the Saint.

“I’m not wearing that. I don’t have any meat on my bones.”

“If you don’t want to wear it, we’ll all swim naked. How’s that, missy?” Merry Lynn fanned herself with a church fan she’d pulled out of her straw handbag. “Start the car, Sudie. I’m melting.”

“Well, roll down the windows.”

“It won’t help till you get moving.”

By the time Sudie had turned the car and headed out of Shakerag, Betty Jewel knew this outing was exactly what she needed.

Surrounded by the hum of tires and the scent of pulled pork Tiny Jim had sent for their picnic lunch, she waited for her first sign of the river. It came to her as the scent of childhood, water so cool and deep it smelled green.

Around the bend, the Tombigbee meandered through ancient blackjack oaks and tall pines, cutting a path that created sloping grassy banks and carved sharp knolls into the red-clay hills.

“Remember that summer I said I was quitting college to marry Wayne?” Sudie found their old haunt, a paradise canopied by spreading tree branches and hidden by a bank of wild privet and honeysuckle. She parked under the deep shade.

“I said you were crazy.” Merry Lynn reached for the quilt Queen had made and the towels she’d brought.

“And I said you should follow your heart.” Advice Betty Jewel would take back if she’d understood how we color another person with our own heart’s desires. What we see is not the truth, clear and unvarnished, but a fantasy built of imagination and stardust.

“Forget that heavy stuff and let’s go have some fun,” Merry Lynn said. “Get the picnic basket, Sudie.”

As they lolled on the quilt, eating pork barbecue, they were reeled backward to a place where the dreams of yesterday might still come true. Betty Jewel could almost believe she’d turned back time.

Afterward, they stretched out on the quilt, side by side, and called out the objects they found in the clouds. Merry Lynn found two angels and Sudie found a frog. When Betty Jewel found a heart, she thought of the locket and felt a pinch of pain that stole her breath.

“Let’s go in the water.” Sudie stood up and peeled off her skirt. “Merry Lynn brought inner tubes. It’ll be like old times.”

“You two go on. I don’t have the strength to struggle into latex.”

A look passed between her friends, and they both started stripping.

“Betty Jewel,” Sudie said, “if you don’t want to see me down on all fours buck-naked, you’d better peel off that dress before I do it for you. I don’t have all day.”

She thought about the cancer that steals all your dignity, and friends who give it back.

“Why the heck not?” She tried to stand up and found herself lifted by Sudie and Merry Lynn. They unbuttoned her dress and folded it onto the quilt, then led her into the shallows and helped her into a black rubber innertube, the kind they’d used as river rafts when they were children.

With the cool green water lapping over her, Betty Jewel leaned back and closed her eyes. For a blissful hour she vanished into the realm of childhood where boundaries between what was real and what was imagined vanished, where things lost might be found, and anything at all was possible, even a future.

When Sudie’s car chugged to a stop on Maple Street, Queen was waiting on the front porch with four yellow plastic glasses of iced tea.

“Did ya’ll have fun, baby?”

“We took her skinny-dipping, Miss Queen.” Merry Lynn plopped on the porch steps with her tea.

“I ain’t never done that, but now I wisht I had.”

Sudie sat in a rocking chair, leaving the seat on the swing to Betty Jewel. “I can’t stay long. I gotta get home and fix supper for Wayne and the kids.”

True to her word, Sudie herded Merry Lynn into the car and drove off ten minutes later, both of them waving out the window, calling goodbye, and Betty Jewel was so grateful for friends who pick you up when you fall that she could do nothing but wave.

“Where’s Billie?”

“I give her a dime an’ she done gone to the movin’-pichure show. Gone see that Tarzan swingin’ on a rope.”

“Lord, Mama, she can’t walk home by herself.” Ever since Alice’s murder, only the foolish let their little girls walk home in the dark.

“I ain’t dum. Tiny Jim gone pick her up.” Queen studied Betty Jewel over the rim of her plastic iced-tea glass. “That newspaper lady’s a comin’.”

“What newspaper lady, Mama?”

“Said her name was Bessie. Miss Bessie Malone.”

Betty Jewel felt like a dying star spinning through the sky, leaving burning bits of herself behind. “Not Cassie. Tell me it wasn’t Joe Malone’s wife.” Queen just sat there with her lips pursed. “You know I can’t talk to her.”

“Maybe it’s bes’ is what I been thinkin’.”

“No, Mama. I can’t talk to her.”

“Lies’ll eat you up inside,” Queen said.

Betty Jewel turned her face from her mama, then wished she hadn’t. Wisps of Alice spun slowly around the yard, phantom legs floating over the grass that needed mowing and arms spread like the broken wings of a little brown bird. But the thing that made Betty Jewel turn away was Alice’s eyes, deep as Gum Pond and clear as mirrors. Look too long into Alice’s eyes and you’d see yourself; you’d see your past bound to your future, the sight so disturbing it could paralyze you.

“What time is Cassie coming?”

“‘Bout five.”

Betty Jewel thought of her options. Hide. Not answer the door. Bar the door and not let her in.

Or let her in and tell the truth.

She’d rather walk into the darkness of her own death than face Cassie with the truth.

Eight

BY THE TIME SHE Left The Bugle, Cassie’s yellow linen sundress was a wrinkled mess. As if that weren’t enough, it was blistering hot in the car. She rolled down her windows, and the first thing she noticed as she drove into Shakerag was the abrupt change from paved streets to dirt roads. Sinking into a pothole big enough to swallow a beagle, her tires spun. As she stomped on the gas, dust swirled through her open windows and settled over everything inside, including Cassie.

Saying an unladylike word that would have given her father-in-law a heart attack, she bumped her way down the gutted road. No wonder unrest was brewing. If she had to travel on roads like this every day, she’d be mad, too. Add to that the mean wages and scarcity of jobs for people who lived in places like Shakerag, and Cassie had to wonder if Ben was right. Was she stepping into a boiling cauldron?

She forged forward, pulled by her own stubborn will and the smell of barbecue that made her mouth water and gave her the shivers all at the same time. There was no escaping the scent of roasting pork on the north side of town. Except on rare occasions, Tiny Jim kept his smoke pits going around the clock.

His blue neon sign was flashing, and, as she drove by, Cassie caught the strains of a soul-searing harmonica. Real this time, not the stuff of myth and magic. The musician could be anybody from a blues legend to some teenage kid with a gut-punched feeling and a harp in his pocket.

The harmonica walked all over Cassie’s heart. It was Joe’s second love. That’s one of the things she missed most: the sound of blues at unexpected moments. She could be in the tub or putting a casserole in the oven or arranging roses she’d picked, when all of a sudden the blues would pull her heart right out of her chest.

Joe, she’d say, and he’d come around the corner, blues harp in his mouth, eyes shining with devilment or laughter or sometimes unshed tears. It was his love of stomp-your-heart-flat music that drew him to Shakerag.

Cassie had begged to go with him, but he’d said, Women don’t go to places like that. Besides, Daddy would disown me if I took my wife to a Negro juke joint.

“I’ve already been there when I interviewed Tiny Jim, and nothing bad happened to me. Even when I drank a glass of sweet tea from their cup.”

“For God’s sake, Cassie. Be serious. Exposing beautiful white women to randy young coloreds is causing race riots.”

“No, the riots are caused by ignorant, hysterical women and hot-tempered men who settle differences with guns and lynching ropes. You’re not ignorant and I’m not foolish. Please, Joe.”

She finally wore him down on his birthday. To avoid unnecessary talk, they took care that nobody in their neighborhood knew where Cassie was going, and, aside from a few raised eyebrows in the juke joint, nothing happened. In their society, white was not merely a color but a privilege, one Joe took for granted and Cassie agonized over.

That evening, he’d driven home with one hand so he could hold his harp to his mouth with the other. The only sound in the car was an old Delta blues song whose words Cassie didn’t know until Joe alternately played and sang.

That was the only time he ever took her, and she’d finally stopped asking to go. She couldn’t remember when. Or why. Or even if she’d ever wondered.

The lyrics Joe had sung on that otherwise silent car trip home suddenly played through Cassie’s mind. Ain’t no use cryin’, baby. The world done stomped us flat. Ain’t no use cryin’, baby. Your tears won’t change all that.

Li’l Rosie had composed that particular blues song. Cassie remembered because she’d asked Joe. She’d wanted to know who knew her so well she’d written lyrics especially for Cassie.

Or had the lyrics been for Joe? Had he been trying to tell her something, but she had looked the other way, shut her ears and walked around him?

Maple Street came into view, but as far as Cassie could see, there was only one maple tree on the entire street. The neighborhood was made up of one wooden saltbox house after the other, mostly unpainted, with a scattering of them featuring washed-out and peeling paint. The rest of the view came to Cassie in snatches—skimpy yards, many of them overgrown with Johnson grass and honeysuckle that will strangle anything in sight if it’s not cut back, old tires stacked under tired-looking oak trees, sagging porches with swings on rusty chains.

Still, they were homes for somebody, raggedy havens where men with grease under their fingernails and women with detergent-cracked hands could lie together on a squeaky bed frame and forget the world outside. The houses sat back from the street on long, narrow lots. Cassie leaned down so she could peer at the numbers tattooed over the front doors.

The frame house she was looking for was painted a pastel blue faded the color of an old chambray shirt, blue gingham curtains at the windows, navy blue shutters, the one on the left side of the small wooden porch pulled loose at the top and hanging crooked. Several scrawny petunias and a few caladiums pushed their way through weeds that were trying to take over the flower beds. The gardener in Cassie wanted to grab a spade and set to work. The reporter saw the dying gardens as a metaphor for their owner.

On the porch an empty swing with a beautiful patchwork quilt thrown over the back swayed as if it had just been vacated.

When she stepped out of her car, an old woman weeding caladiums next door glared at her with such outright hostility, Cassie had to look behind herself to make sure she wasn’t trailing trouble like a blood-stained shawl. She waved and smiled, but the woman stomped inside her house and slammed the door.

What kind of reception would be waiting inside this Shakerag house? When the front door opened, Cassie startled like a cat with its tail in a washing machine wringer.

Miss Queen stood poised behind the screen door. It could be no other, for she looked much the way she had when Cassie had seen her at Tiny Jim’s, pounding out the blues on his old upright. It had been so long ago she couldn’t remember. Ten years? Fifteen? Miss Queen’s face was a map of years, her dress sprigged voile from a vanished era. She had dressed for Cassie. Suddenly she was glad she was wearing her yellow linen dress instead of her usual garb of slacks and a blouse. It seemed more respectful somehow.

“Good afternoon. I’m Cassie Malone from The Bugle.”

Miss Queen unlatched the screen door, but not before she’d put a gnarled hand to the white lace collar at her throat. When Miss Queen stepped onto the front porch, Cassie thought of the Titanic—a ship capable of taking care of thousands of families, a ship that nothing could fell save an iceberg.

“Pleased to meet you, ma’am. I’m Queen. Queen Dupree.”

Cassie climbed the steps onto the porch, and the old wooden floorboards creaked. Through the screen door drifted the mingled smells of lemon furniture polish and freshly baked pies overlaid with the strong fragrance of barbecue. The legend at work or proximity to Tiny Jim’s? Either way, the scent gave Cassie the shivers.

“I remember you from Tiny Jim’s.” Cassie offered her hand to Miss Queen. “You and your daughter used to play piano there.”

“Yessum.” Queen peered closely at Cassie, squinting in the way of the nearsighted, but she didn’t take her hand. Cassie felt foolish. Coloreds didn’t shake hands with whites, not in this ancient, dignified woman’s world. “I seen you there some years back.”

In the way of old people comfortable with who they are and not about to put on airs to impress anybody, Queen didn’t try to hide the fact that she was studying Cassie. Did she pass muster? She wished she’d taken the time to go home and put on a dress without wrinkles. For Pete’s sake, she hadn’t even bothered to comb her hair. She must look as if she had on a Halloween wig.

“I came to see your daughter.”

“Yessum. Do come in, Miss Cassie. She’s waitin’ on you.”

Queen led her down a hallway filled with pictures. The centerpiece was Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane. In the place of honor on his right was the photograph of a little girl with cheekbones slashed high, eyes too big for her thin face and lips compressed tightly together as if she were daring the photographer to make her smile. Something about her eyes made it hard to look away. The arresting shade of green? The frank stare?

Other photographs chronicled her life from laughing babyhood to gap-toothed schoolgirl. Betty Jewel’s daughter, Cassie guessed. Who would take her picture in her cap and gown? Her wedding gown? The pink quilted robe she’d wear home from the hospital when she had her first baby?

Cassie hoped her story would make a difference. Shouldering the awesome responsibility, she followed Queen into a sunlit room where a gaunt woman sat in a rocking chair, staring out the window. Though it was so hot in the house Cassie was beginning to sweat, the woman was wearing a shawl.

“Betty Jewel, honey, look who’s done come to see us. That newspaper lady.”

Betty Jewel’s shoulder blades stuck up through the crocheted shawl like the wings of a skinny-legged bird. The flesh had disappeared from her bones, leaving behind too much skin. But when she saw Cassie, she lifted her chin. It was pride Cassie saw.

“Hello, Cassie. Please do sit down.”

There would be no yessums and Miss Cassie this or Miss Cassie that from Betty Jewel Hughes. Dying strips you of all pretense, carves you down to the essentials.

Betty Jewel’s voice, rich with melodious cadences, was mannerly, but her eyes said keep out. Her posture said don’t mess with me.

Cassie sat in a straight-backed chair closest to the oscillating fan. Words weren’t enough here. She needed to take action. She needed to lasso a couple of guardian angels and say, Look, do something.

“I’m gone leave you two young’uns by yoself so’s you can talk.”

The old woman slipped from the room, leaving Cassie with her purse in her lap, wondering why she felt Betty Jewel’s hostility like a cattle prod. She had to know the consequences of Cassie being here, the gossip she’d endure from the Highland Circle crowd, as well as the suspicions and tongue-waggings of Betty Jewel’s neighbors.

“May I call you Betty Jewel?”

“Suit yourself.”

If Cassie’s maid or her gardener spoke to her like that, she’d fire them on the spot. But in Betty Jewel’s home, Cassie was the outsider. Nothing insulated her in this shack in Shakerag, neither wealth and position nor the color of her skin. It looked as if she had finally let her crusading zeal get her into a situation she might not escape from unscathed.

She tried to melt her unbending hostess with a smile. “I don’t mean to be nosey. I’m here to help you.”

“I don’t need your help, and I certainly don’t need you poking into my private business.”

“Look, I’m no do-gooder who just barges in. Your mother invited me.” Cassie felt her temper rising, and it showed. At the rate she was going, she’d be back on the street before her hubcaps got stolen from a flashy car that obviously didn’t belong in this neighborhood any more than she did.

“Mama shouldn’t have told you to come here. She may sound like some shuffling, obsequious old mammy, but she’s a proud African queen. And so am I.”

The naked expression on Betty Jewel’s face made it painful to look at her. Cassie catalogued the facts. A woman that well spoken had probably attended one of the Negro colleges down in Jackson or the Delta. No doubt Queen had sacrificed to make sure her daughter had a better chance in life. And now Queen’s daughter was making the ultimate sacrifice to ensure her child’s future.

Giving up a daughter in order to save her was a choice of biblical proportions.

Reining in her temper, Cassie held out her hands, palms up. “Look, I’m out of my element here, and you must be feeling as uncomfortable as I. Can we please just start over?”

Betty Jewel bowed her head and stayed that way for a long time. Was she pulling herself together? Regretting her rudeness? Wondering if she’d insulted the wrong person?

Negroes were being lynched for less. With racial violence flaring all over the South, had Cassie jeopardized the safety of this family simply by being here?

“I’m sorry.” She stood up to leave. “I didn’t mean to make things harder for you.”

“No, wait.” Betty Jewel’s eyes were wet with unshed tears. “All I can say in my defense is that cancer has made manners seem superfluous.”

“I’m so sorry. I can’t say I know what you’re going through, because I don’t. But I lost my husband a year ago, so I can certainly understand pain.”

“You and Joe never had children, did you?”

Her familiarity with Cassie’s life was startling until she remembered all those evenings Joe had spent at Tiny Jim’s. Though Joe would never spread his personal life among strangers, he was a well-known public personality. And in a town as small as Tupelo, the gossip grapevine flourished.

“No, we had no children.”

The conversation reminded her all too vividly of the many ways she and Joe had found to blame each other for their childless state. Joe was dead. She wanted him to remain perfect, but a thick blue fog clouded the room, seeding discontent and making sanctifying the dead impossible. If you weren’t careful, you could get lost in that kind of fog and never find your way home. Searching for something solid to hang on to, Cassie spied the piano.

“Tell me about yourself. You play, don’t you?”

“I’m dying. What else is there to know?”

There was no barb in the remark, only soul-searing truth. Cassie took a notepad and pencil from her purse. “Please understand that I’m only here to write a story that might help you find a home for your child.”

Inscrutable, Betty Jewel slipped a pill out of her pocket, then washed it down with a sip from the yellow plastic glass on the table beside her. “Does it make women like you feel good to help women like me?”

Cassie felt as if she’d been slapped. She had better things to do than seesaw between rage and pity with Betty Jewel, even if the woman was desperate.

“You don’t even know me. If you did, that’s the last remark in the world you’d make. I consider us the same.”

“You mean equals? Like I can walk through the front door of your white house and go into your white bathroom without you going in there after me and scrubbing it down with Dutch Boy?”

Anger and admiration warred in Cassie. She thought of Bobo, her gardener, and Savannah, her maid. Had she ever invited them to sit down at her table and enjoy a glass of iced tea? Cassie was beginning to feel like a hypocrite until she remembered how she inquired about their children, went to their homes with soup when one of them got sick.

“Yes,” she said. “Exactly like that.”

Betty Jewel fell silent, her steady stare saying that when you’re dying your life is reduced to the essentials. Eat, sleep, breathe. Tell the truth. The dying don’t have time for lies.

“I’m sorry, Cassie. I’ve been rude and arrogant, and I’ve misjudged you.”

“Thank you. Now will you please give me something I can put into a story?”

“There’s not going to be a story. That ad was a mistake, and I don’t intend to compound it with a news spread I have to hide from Billie.”