Полная версия

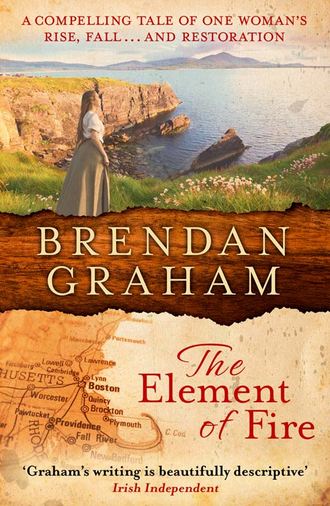

The Element of Fire

‘So, they have become nameless?’ she replied brusquely.

He looked at her, surprised at her obvious lack of geniality.

‘If they are all to be called “Bridget”, then they are all without identity,’ she stated, with little patience.

‘Oh, not all, madam!’ the gentleman from Chestnut Street assured her. ‘Our “Bridget” is a Mary, and next door’s is an Ellen; they are all named with their own names, eh, before becoming “Bridgets”,’ he explained, wondering at her slowness, and why on earth Peabody had ever introduced them in the first place.

Whatever about the turmoils Boston was experiencing with Bridgets or otherwise, she and Lavelle settled into a happy and tranquil state. ‘A pool of contentment’, was how Mrs Brophy (‘Wasp-waist’ to Lavelle) described it. Harriet Brophy had an opinion on most things in life – and most people. Furthermore she was not one bit backward about coming forward with these opinions – in whatever company she might find herself.

‘He, Mr Lavelle, is such a dashing man, always good-humoured. It was made in Heaven … made in Heaven, Mrs Lavelle, as my own and …’ she added quickly, ‘… all good marriages most surely are,’ she informed Ellen.

Ellen, was careful not to reveal too much of anything to Harriet Brophy, for by the following Sunday after Mass the whole parish would have it. But ‘Wasp-waist’ was right about her and Lavelle. They were ‘a pool of contentment’. Lavelle was everything the woman described him as and more, being as well an industrious worker and a good father to her children and ‘the fosterling’. Ellen knew he would have liked a child of his own and she was full in her desire to grant him that wish. But so far they had not been blessed.

Lavelle never asked, but every month or so he would look at her. When she said nothing, she would see the hope dashed from his eyes. But it never lasted with him, nor did he ever attach any blame to her, saying only she was the ‘plenty of all happiness’ in his life.

Once she had told him that for the six years before Annie was born, she had been barren.

‘She must have been born hard,’ was all he said, ‘taken a lot out of you.’

Sometimes of an evening he spoke of Australia, its vast bushland, its sounds, its redness. She neither naysayed nor encouraged him in this. Australia had been a dark experience for both of them. But it had, after all, been where she had first met him.

‘You miss it,’ she stated, during one such reminiscing.

‘I suppose I do, Ellen,’ he told her. ‘I grew up on an island, wild as winter. Australia always reminded me of that wildness, though it was hot and red instead of wet and green. I miss the wide-open spaces, the smell of the gum trees – the silence. This Boston’s a noisy place.’

‘It is that,’ she replied.

‘Would you ever return?’ he asked, turning the question on her.

‘No …’ she said, ‘… to neither. Australia is a far country and Ireland even farther in my mind. I’ll do with being buried in America.’

12

Whatever about dying in America, living in America was an excitement that barely disguised itself. There was always something happening, some new discovery. She followed the newspaper reports of how life was progressing in her adopted homeland as assiduously as ever.

‘See, Lavelle, all we need is a chance! A chance to prove ourselves. We can be as good as the rest!’ she said, reading of how the electric telegraph, developed by two County Monaghan brothers, had carried a message from President Polk throughout the United States. ‘They have five thousand Irish employed and are as well building a railroad across Panama to join the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans!’

Lavelle was not so impressed. ‘And why wouldn’t they, at a dollar a day on the broken backs of their countrymen?’

‘Lavelle, why do you always down your own, those who have advanced in America?’ She was annoyed with him.

‘Because if we don’t say how America was built – at what cost – then it will all soon be forgotten,’ he answered. ‘Forgotten that Paddy’s shovel filled the coffers of this Commonwealth, the same way that Paddy’s green fields filled the granaries of the British Commonwealth. Everything has a price.’

‘At least the Paddies here have a chance, a chance to be part of this Commonwealth,’ she answered him.

‘Commonwealth me arse!’ he said, forgetting himself.

She ignored his outburst. ‘You’re still caught up in the wrongs of Ireland, and all of that … all of what we’ve left behind us,’ she said, calmly.

‘But have we left it behind us, Ellen?’

‘Well, I have,’ she said, more firmly.

Her assiduousness in gleaning every scrap of new information from the periodicals and magazines led her to a most unexpected bounty – Mr Horace Mann, an educator of high standing.

She read how Mann, following travels in Europe, had published a report on a new departure in the education of deaf-mutes, a sort of ‘silent talking’, advocating it be introduced to the schools in America. Her hopes were raised for Louisa and she pursued this new avenue whereby in Germany ‘the deaf can now read on the lips, the words of those who address them, and in turn use vocal speech’.

When, all of an excitement with this news, she sat them down and through Mary tried to explain it to Louisa, she was met with total indifference. Not the hazelnut eyes sparkling with hope as Ellen had expected. Not the joy such news must surely bring. Louisa, it seemed, did not want to be liberated from her affliction. Almost as if she wanted to remain locked away in her own silent world, Mary to be the sole key-holder.

It perplexed Ellen. She tackled Mary on the matter.

‘I think she’s afraid of something,’ Mary told her.

‘But what, Mary? It can only be to her benefit.’

‘I don’t know, Mother. She wouldn’t tell. Maybe she likes being the way she is … not part of everything.’

That night, she tucked Louisa into bed, prayed with her as always, whispering the prayers up close to the girl’s face, so that Louisa could at least see the shape of their sounds, feel them, if nothing else. The child, hands angelically clasped, lay there, eyes fixed on her adoptive mother’s lips, until the final breath of blessing. Then Ellen folded Louisa’s arms across her bosom in the shape of a diagonal cross, pulled the bedclothes up about her neck, and pressed her lips to Louisa’s forehead. She sat with her longer than usual, caressing the girl’s brow, soothing her to sleep, with touch and talk.

‘It’s all right, Louisa dear, you won’t have to do it any more. Sleep now, and don’t be fretting yourself. I only wanted what I thought was best, but maybe I was wrong. Maybe, after all, I was wrong.’ She put her face next to Louisa’s, fingered the hair back from her far temple. ‘My little fosterling.’

She remained until Louisa had fallen away from the world and its noise.

Despite the huge influx of paupers, these years were Boston’s golden years and the city continued to grow and prosper in every direction. At the Massachusetts General Hospital, an ether anaesthetic had been used on the operating table for the first time. It was the start of a new era in surgical medicine. Where previously brandy and even opium had been used, now ether – the ‘Death of Pain’, as Bostonians proudly proclaimed, had arrived.

The ether of the Irish – alcohol – continued to provide the ‘death of pain’ of deprivation, disease and displacement, suffered by the city’s immigrant population. This, despite the fact that Ireland’s Temperance priest, Father Mathew, had visited the city to admonish the frequenters of Boston’s twelve hundred taverns about ‘the evils of the bewitching glass’. But nothing, it seemed, not even the ethered Irish, could hold back the city’s progress.

Added to its horse-drawn streetcars, on which one could travel for a nickel, Boston now had eight railroads, bringing twenty thousand people daily into the city. She vowed that one day she would travel every single one of its new iron roads.

The Cochituate Water System had already opened to meet the increasing demands of a swelling population and much to the delight of Boston’s children, the Frog Pond on the Common was now regularly filled with water from Lake Cochituate. She had taken the children there when first it opened and Mayor Josiah Quincy had ordered a column of water to rise eighty feet above the Pond – immortalizing himself in water with a sky-high statement that Boston’s citizens would never again be short of it.

There was nothing, it seemed, Boston and its citizenry could not achieve. The city filled her with a breathlessness as much for herself as for what it opened up for her children. Regularly, she brought them to the Frog Pond, to skate and tumble and laugh on its winter ice, to wade in its cooling waters in the summer, often taking one of the horse-drawn trams to make it a special treat. The Long Path, which diagonally traversed Boston Common, was her favourite stroll, a walk long favoured by those in love. She explained its tradition to them.

‘A young man, too timid, perhaps, to directly propose to his Boston beauty, would ask, “Would you take the Long Path with me?” If she said “Yes” it meant she would marry him. They would never part. But,‘ Ellen paused, ‘if she stopped to rest – here perhaps, under this gingko tree, it meant she didn’t love him.’

‘Oh …’ said Mary, looking around for the ghosts of lost love, ‘that’s so sad – but at least she’d not said “No!”.’

‘That was it!’ Ellen explained. ‘The young man was spared that embarrassment. So ladies, if any young beau asks to walk the Long Path with you, consider carefully if you should rest along the way,’ adding, ‘I’m sure no young lady of Patrick’s choice would ever rest!’

Patrick, however, was not impressed and though he regularly accompanied them to the Common, at fourteen was less interested in marriage-making than in watching the haymaking, a custom that still persisted. Unless, of course, she recounted stories of Paul Revere and the Sons of Liberty, and the military history of the Common, long a mustering-ground for armies of every flag and allegiance.

The Great Elm commanded attention from every element of the family, even boys. The giant tree, whose protective branches offered one hundred feet of shade, stretched heavenwards for seventy or eighty feet. But if Heaven was its aspiration, Hell was its application, for the Great Elm was once a place of executions. Witches, martyrs, adulterers alike, all swung from its gallowed limbs. United in fascination, all three would close in around her, fearing its embrace, wanting none the less to hear its dark history retold yet again. Tales of ‘the Puritans’, or of ‘the Reverend Cotton Mather’, who stalked the condemned, seeking to save their souls from a fate worse than death – eternal damnation!

‘Tell us Mary Dyer!’ Mary asked, though by now they knew the story well.

The Quaker girl had left the early colony, protesting the banishment of another young woman dissenter. On her return she was imprisoned and saved only from the tree by her son. Instead of her life she was banished for ever from the Bay Colony.

‘Mary came back again,’ Ellen told them in hushed tones, ‘to fight for her freedom. But the death sentence previously given had not been lifted. Mary still refused to repent, because she had done no wrong.’ Ellen paused, looked into the branches above them, before delivering the final verdict. ‘So the Great Elm took Mary Dyer.’

‘And her ashes were scattered on the ground here,’ the young Mary O’Malley put forward, fearfully.

‘Yes, we should be careful where we tread,’ Ellen told them, herself almost frightened by the notion of it.

The Great Elm where the dead and the living came together had a sobering impact on all of them. Yet, time and again, Ellen was drawn back to it. Sometimes, she would sit alone there, waiting for them while they played. It reminded her of the Reek – strange, silent, overshadowing. More than its trunk and limbs was the Great Elm, just as the Reek was more than its rocks and steep crags. Tree and mountain, both seemed to her to be warnings posted on the path of life. Grim, penitential listening places, for the strayed and the wayward. While the Long Path had its whisperings of love, the Great Elm had other darker intimations. Of love betrayed. Murmurings too of the terrible consequences its infamous gibbet had wreaked on the necks of those betrayers. She had yet not told them those stories, lest, in innocence, they should have sympathy for adulterers.

13

It took her into the following spring ‘to put a shape’ on No. 29. But she was not foolhardy, hunting down bargains – crockery ware on Washington Street, ‘sensible’ curtains from the Old Feather Store, a thick-in-the-hand, good-wearing Turkish counterpane for the floor of the good room; sturdy chairs, slightly shop-soiled, a chip or two gone from them but still perfectly good for sitting upon.

Lavelle did the heavy work – painted and decorated and put a snas on the backyard. Then Patrick wanted to ‘get at’ the gone-to-seed cabbages, but at her request left it. She decked the front and back borders of the cabbage patch with small yellow flowers – a Latin name, ending in ‘ium’ – she couldn’t remember when Mary had asked her. Peabody had told her when he’d given her the seeds, but she’d forgotten. The other two sides she left open, so she could ‘pluck the new cabbages, when they grew’, she hoped.

Eventually, the house was the way she wanted it; for the moment, at least. She had one other idea for the good room, but that could wait a while.

Lavelle, who had always maintained close links with those Boston Irish interested in the ‘Irish Cause’, had recently begun to attend meetings for the repeal of the Union of Ireland with England. She would have preferred he didn’t, that he’d leave ‘the past to the past’. Lavelle’s view was that ‘the past never goes away – the past is a road – always coming from somewhere and leading somewhere else’. She couldn’t win with him, so she gave up trying. She did once remark that with his increasingly frequent absences on ‘matters of Ireland’, ‘Now that the house is settled here, I have a mind to move back to Washington Street – and you could pay court to me every evening, as before!’

He knew she wasn’t serious, grabbed her and kissed her, laughing as he exited the door.

She read, instead, sitting at the rosewood bureau he had restored, her book on the baize-covered writing surface, vanishing her away from the world.

Her visits to the Old Corner Bookstore had been less frequent since they moved here, yet more precious. So that when she did go there she lingered over its store of treasures, lovingly fingering the gold-lettered spines, imprinting into memory the works and the lives within. The English poets: Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads, Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience – the two contrary states of the human soul – Byron and Donne. These were her favourites, opening her eyes to an England, pastoral, passionate, spiritually provocative, different from the ‘perfidious Albion’, she had known, an England of Cromwell and Queen Victoria, ‘The Famine Queen’.

At Christmas, Lavelle had presented her with Legends of New England, in Verse and Prose, by the Massachusetts-born John Greenleaf Whittier – ‘to wean you away from old England’. And she was much interested in New England writing. Emerson with his spiritual vision, his belief that all souls shared in the higher, Over-Soul, that nature is spirit, rang with a resonance close to her own, one which the organized pulpitry of the Catholic Church could never achieve for her. The women writers of New England, she also sought out, as much for their ‘Bloomerist’ agenda as for anything. However, the Old Corner Bookstore, Lavelle’s ‘Repeal’ meetings, and even the aggrandizement of No. 29 were only the trimmings of life in Boston. The education of her children, the steady growth of the business, and the unerring stability of life in general was what mattered, what she had always craved. What now was within her keeping.

The children all were flourishing. Patrick at the Eliot School, Mary, and even Louisa, with a little additional schooling from Mary, at Notre Dame de Namur. Peabody had now opened yet a further store, his third, in the affluent suburb of West Roxbury. And she had settled more easily than she had expected into the marriage life, seldom a cross word between them, Lavelle, unlike many, remaining sober in manner. Mrs Brophy’s ‘pool of contentment’ continued to surround them, if not indeed deepen.

She thought that maybe the time was now right to try again some of Boston’s better establishments which had once refused her, given that they themselves were better consolidated now. But upsetting the arrangement with Peabody worried her.

‘We are too much in his hands already,’ was Lavelle’s view. ‘I wouldn’t put it past Peabody to go directly to Frontignac himself. What’s stopping him – except you?’ he added, teasingly.

She swiped at him with her apron. ‘You might be right, Lavelle,’ she teased back, ‘but underneath everything, Jacob is all business,’ adding more seriously, ‘he is at no risk financially. That is what’s stopping him. He doesn’t pay until he sells. Nobody else affords him that arrangement.’ She paused. ‘But if we are to give the same terms to enter business with others, then what little reserves we have will be strained. We will need to approach the banks – or R.G. Dun, the credit agents!’

‘Well we didn’t give it to Higgins …’ Lavelle started, referring to the customer he had secured while she was in Ireland; a steady, but not startling account. ‘I mean, I wouldn’t …’ he corrected himself, so as not to appear critical of her arrangement with Peabody. ‘The city is bursting at the seams. It cannot develop quickly enough. There is such wealth here that we can scarce go wrong by expansion, and without having to extend excessive credit,’ was Lavelle’s final word.

She told Peabody of their plan, reassuring him that they would not supply anybody within a certain radius of his own stores.

‘I wondered how long it would take you. Of course, you must expand – God forbid anything should happen to me!’ was all he said. ‘Come, sit now a while and we will discuss life, instead of business – all only business with you Irish,’ he mocked.

She was relieved at his generous response. There were times when Jacob seemed more interested in philosophy than profit, and she did love these discussions with him. He seemed to know so much, quoted freely from poem and psalm alike and had such seeming wisdom. How like her father he was in that respect. Yet, unlike the Máistir, Jacob never revealed much about himself; his defence to veer off into being flirtatious with her, if she probed too deeply. Not that he needed much excuse for that either.

Jacob, how did you come to know so much … of everything?’ She had decided to try some probing of her own. ‘Was it from your father or through schooling?’

‘Neither,’ he quipped, ‘but from gazing into the eyes of beauty. Much wisdom is to be found there.’ Then he turned it around, asking questions of her. ‘That song at your wedding – I was reminded of it again recently,’ he began. ‘The “Úna” in your song intrigues me. Love beyond death? Death in love? Which is it?’

She laughed; he always did this. ‘It is both … it depends,’ she answered vaguely.

‘On what?’

‘On the love, the lovers – you know that, Jacob!’

‘And is this love a common thing, do you think, or only in songs?’ he pressed.

‘It is uncommon. If it were common, it would not be written about.’ She tried to bring the discussion back within the framework of the song but Peabody was having none of it.

‘So, there is love and there is love. One, the common kind for the many and the other – great, tragic love – for the few. Is that it?’

She knew where this would lead. He could be wicked, Peabody, the way he forced her to uncompromise her thinking.

‘Yes … I suppose so, Jacob,’ she parried.

‘What begets the difference, Ellen Rua?’

It was the first time he had called her that since she had spoken of it to him on her return to Boston – about how she had shortened her name, dropped the ‘Rua’.

‘I don’t know, Jacob, and don’t call me by that name.’ She stamped out the words at him.

‘Do you know the Four Elements of the Ancient World, Ellen … Rua?’ he repeated provocatively.

‘Of course I do!’ she said, angry that he still persisted with her old name. ‘Earth, wind, water, fire,’ she reeled them off.

He held up his hand. ‘Fire – that is it, the Element of Fire. That is what begets the difference, Ellen Rua.’

Sometimes he was hard to follow, the way his mind twisted and darted.

‘The Element of Fire? What on earth are you talking about, Jacob?’ she asked. ‘And I told you – it’s Ellen!’

He ignored her reprimand. ‘That is the difference between love for the many and love for the few – the Element of Fire,’ he answered, as if it were all self-evident. Then, seeing the look on her face, he continued, ‘Fire smoulders, it burns, it rages, it purges and purifies, it engenders great passion … and it destroys.’ He paused, took her hand as if passing some irredeemable sentence on her.

‘You were named for fire, Ellen … Rua.’

The talk with Peabody had unsettled her. What was he at with such a statement? That she was named for fire, the element that destroys! Jacob was trying to bait her, to stir something in her. Maybe some tilt at Lavelle and herself? But why? While Peabody was dismissive about Lavelle, he was hardly suggesting that she didn’t love him, that it was merely a marriage of convenience? You never knew with Jacob. Sometimes she felt that if she were to encourage him, he would be quite willing to draw down the shutters, pull her into the storeroom, and fling her on to the nearest flour sack, or chest of tea from the Assam Valley.

He was capable too. More than once when he embraced her, he had pushed in close to her, so that even through her underskirt she could feel his ‘scythe-stone’. Whatever about Jacob’s ‘scythe-stone’, his mind was sharp and dangerous, always trying to cut through her thoughts, to lay them bare.

She didn’t speak to Lavelle about her discussion with Peabody except to say, ‘My fears were unfounded, Jacob was most generous at the news.’

‘I don’t trust him, Ellen; and neither should you,’ was Lavelle’s response.

‘He has always been upright in his dealings, give him some credit,’ she defended Jacob with.

‘It’s not in their nature, the Jews.’ Lavelle would give no ground to her argument. ‘While there’s money to be made, they’re trustworthy. When more is to be made elsewhere, then see how far their trustworthiness stretches,’ he challenged.

‘Lavelle, you can’t say that. They’re not all the same, no more than all the Irish are fighters and drunkards,’ she retorted.

But Lavelle was not for turning. ‘History teaches us – didn’t they betray the Saviour for thirty pieces of silver?’

‘That was just one, Judas,’ she responded.

‘Yes … His friend,’ Lavelle retorted. ‘Kissed Him and betrayed Him, and the rest – all Jews – stood by while it happened. How well the like of Peabody got started here. The wandering Jew will get in anywhere.’

‘Jacob was our saviour when –’ she started to protest, but he cut her short.

‘I know you and Peabody have talks, and I know, too, that at the start, he was our saviour, but he is too familiar in his talk with you, and,’ he added, ‘how he looks at you!’

So that was it. How could Lavelle possibly think that Jacob was a rival for his affections? Nevertheless, this side to him pleased her somewhat, and brought a small flush to her neck. She went to him, embraced him.

‘Oh! Lavelle, please stop it!’ she chided. ‘You know he looks at every woman under fifty years of age like that, it’s just his way. Jacob has never made any indecent approaches to me – yet,’ she teased.