Полная версия

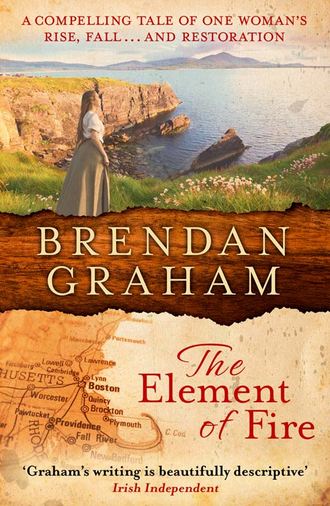

The Element of Fire

‘I’m clean enough! I don’t need you to wash me!’ elicited no sympathy. She was taking no chances after the episode with the boy and his dead brothers – who knew what they carried? She rolled up her sleeves and scrubbed him to within an inch of his life, until his skin was red-raw. He thrashed about in the water trying to get away from her but to no avail. She did not relent until she was satisfied he was ‘clean’, until she had found every nook and cranny of his body. Then, lugging him by each earlobe in turn, she stuck long sudsy fingers into his ears, to ‘rinse’ them. When she had finished he was like a skinned tomato. Sullen, jiggling his shoulders so as not to allow her to dry him with the towelling cloth. She gave up, threw her coat over his shoulders and led him back to the room. ‘Dry yourself, then,’ she ordered him.

The two girls she put together into the tub. She was not so worried about them. But even from Katie they might have taken something; and much as she didn’t want to think of it, she had to be careful about that too. Disease passed from person to person, even from the dead to the living. Ellen thought the girl would be shy about letting her touch her. This proved not to be the case. Mary, though, seemed to recoil from the girl, not wanting their arms and legs to touch, get entangled. Maybe it was a mistake putting them in the bath together, so soon after Katie. She was as gentle as she could be with Mary, kept talking to her.

‘Katie is with the angels in Heaven, with the baby Jesus … with –’ She paused, thinking of Michael, the hot steam of the tub in her eyes. ‘I was too late … too late a stór … but they’re looking down on us now … it was hard, Mary, I know … and on Patrick … and Katie too, with your poor father laid down on the Crucán and me fled to Australia. What must have been going through your little minds?’ Maybe it would have been better if she had taken Annie and with the three of them, crawled into some ditch till the hunger took them instead of her splitting from them. But how could she have watched them waste away beside her, picked at by ravens, their little minds going strange with the want of a few boiled nettles, or the flesh of a dog. She thought of the boy and his brothers – or any poor manged beast that would stray their way. She had had to go, it was no choice in the end – leave them and they had some chance of living, stay and they all would surely die.

Mary, head bent, said nothing, her hair streaming down into the water, red, lifeless ribbons. What could she say to the child? She pulled back Mary’s hair, wrung it out, plaited it behind her head.

‘God must have smiled … when He took Katie. He must have wanted her awful badly …’

Mary turned her face. ‘Then why did He leave me?’ she asked limply, boiling it all down to the crucial question.

‘I don’t know, Mary,’ she answered. ‘There were times when I prayed He’d take all of us. He must have some great plan for you in this life,’ she added, without any great conviction.

How could the child understand, when she couldn’t understand it herself – the cruelty of it – snatching Katie from them at the last moment. She fumbled in her pocket, drew out the rosary beads.

‘The only thing is to pray, Mary; when nothing makes sense the only thing is to pray, Mary,’ she repeated.

Already on her knees, arms resting on the bath, Ellen blessed herself.

‘The First Joyful Mystery, the … the Annunciation,’ she began.

They had to have hope in their hearts. The sorrow would never leave, she knew, and maybe there would never be full joy in this life. But they had to have hope, keep the Christ-child in their hearts.

She and Mary passed the Mysteries back and forth between themselves, each leading the first part of the Our Father, the Hail Marys and the Glory be to the Father as it was their turn. Once, before the Famine, there were five of them – a Mystery each.

The silent girl gave no hint that she had ever previously partaken of such family devotion, merely exhibiting a curious respectfulness as the prayers went between Ellen and Mary through the veil of bath-vapour – the mists of Heaven. Ellen’s clothes were sodden, her face bathed in steam, the small hard beads perspiring in her hands. The great thing about prayer was that you didn’t have to talk to a person while you prayed with them. Yet souls were joined talking to each other, while they talked to God. She beaded the last of the fifty Hail Marys. There was only so much time for prayers and she whooshed the two out of the tub before they could get cold.

Afterwards, she boiled all of the clothes they had worn, along with her own, before at last climbing into the tub herself. It was a blessed relief. When she had finished rinsing out her hair she lay there, head back on the rim of the tub, her eyes closed. Everyone and everything done for. A little snatch of time to be on her own. Just her and Katie.

The memories flooded back to her. How when she’d send Katie and Mary to the side of the hill for water, they would become distracted, forget. Instead, would lie face-down on the cooling slab of the spring well, watching each other’s reflections in the clear water. Then, when she called them they would scamper down the hill to her, pulling the bucket this way and that until half its contents was left behind them. The times when she did the Lessons, teaching them at her knee what she had learned at her father’s knee, passing it on. While Mary would reflect on what she had learned, Katie just couldn’t. Always bursting with questions, one tumbling out after the other, mad to know only about Grace O’Malley, the pirate queen of Clew Bay, or Cromwell and his slaughtering Roundheads. God, how Katie had tried her patience at times! The evenings, when as a family they would kneel to say the rosary, Katie’s elbowing of Mary every time the name of the Mother of God was mentioned, which was often! At Samhain once when the spirits of the dead came back to the valley, Katie had thrown one of the bonfire’s burning embers into the sky. No amount of argument could shake her belief but that she had hit an ‘evil spirit’ with it.

That was Katie, a firebrand herself, filled to the brim with life. But she had the other side too; like the time she had dashed to the steep edge of the mountain as they crossed down to Finny for Mass. It had put the heart crossways in Ellen. But Katie had returned safely and clutching a fistful of purple and yellow wildflowers, a gift for her mother.

Her fondest memory of Katie was of the time when Annie was born. Katie had crept to her side, to be the first one to see ‘my new little sister’. Like an angel touching starlight, one tentative finger had stretched out to touch Annie’s cheek. How Ellen herself had cried at the beauty of the moment, then laughed at her own foolishness. Katie, as always, asking the ever-pertinent question. ‘A Mhamaí, why are you crying when you’re laughing?’ And she couldn’t answer her. They had lain there together, she and Katie and Annie, into the gathering dawn; touching, whispering, rapt in wonder until the others came. Both of them now snatched from her, Annie in far-off Australia, Katie on her own doorstep.

‘You in there!’ The loud rap at the door startled Ellen. ‘You’ve been there all night, we have others waiting!’ The gruff voice of Faherty’s cousin was matched by further rapping.

‘I’m sorry,’ she called back, clambering out of the tub, ‘I’m coming.’

She was relieved when she opened the door to find he had gone downstairs. Briskly she padded along the corridor, marking it with her wet footprints, the only sound ringing in her ears, not that of the gruff innkeeper but a child’s question.

‘Can we make wonder last, a Mhamaí?’

And her answer, those two and a half years ago. ‘Yes, Katie, we can.’

Back in the room, Patrick, Mary and the girl were already asleep. She dried herself freely, nevertheless, keeping at a discreet distance from the window in The Inn’s west wing. The window looked out across the Carrowbeg river. Directly opposite she could see St Mary’s Church, with its imposing parapet. The thought of the boy with the sack being evicted from the House of God because of his wretched condition angered her. Why had she felt responsible for the boy – as she had for the silent girl? Why for some and not for others, when thousands were dying? Faherty had told her thirty-nine poor souls had received the last sacraments in that day alone.

‘And it’s the same every day, ma’am. Monday to Sunday. They say there’s thirty thousand of the destitute getting outdoor relief around here – they’ll be joining with them soon enough.’

She could well believe it. Thirty thousand in one small area. She wondered if there was any hope for the country at all. But why didn’t she feel as bad about these, about the nameless hordes, as she did about the boy? She had never asked his name. That way, he was just a boy, any boy. But she was ridden with guilt when after giving him some food and a few coins with which to send him off, he had thanked her saying, ‘I’ll pray for you, ma’am.’ Faherty was right, she couldn’t save them all. But what would the child do, where would he go? For how long would he survive?

The limestone façade of St Mary’s looked back white-faced at her from the South Mall. Nothing much had changed since she had left Ireland. If you had money you lived proper and you died proper, as Faherty might have put it. You had the Church behind you. Otherwise it was a pauper’s life and a pauper’s grave.

This thought reminded her she needed to be careful with the money. She had depleted what she had carefully squirrelled away over many months in Boston, by coming to Ireland. Now, with The Inn, and who knew for how long, and the extra cost to Faherty for the two coffins, she had eaten further into her reserves. The silent girl could only come with them because Katie wasn’t. If they had long to wait in Westport, Ellen might not even be able to afford that passage. She would be forced to leave the girl behind. At one stage, she had almost decided to disentangle herself from the girl and give her to the nuns, if they’d take her.

The waif, who watched and shadowed her everywhere, seemed to be a manifestation of the past dogging her, a spectre of loss, separation, Famine. It unnerved her the way the girl never asked anything of her, just was there like a conscience. But, given a little time, she might make a companion for Mary. Not that anybody could replace Katie; it wasn’t that. But maybe Mary might find some echo of her own unvoiced loss in the silence of the mute girl, some small consolation in her companionship on the long journey across the Atlantic.

Now, Ellen prayed across the waters of the Carrowbeg to the House of God that she would not have to change that decision. She closed her mind from even having to think about it. Instead, she tried to recall what it was Faherty had said about the church opposite. About the inscription from the Bible that its foundation stone carried?

‘This is an awful place. The House of God.’

Faherty knew all these things.

4

The days dragged by. Each day she trudged with the children to the quayside and scanned out along Clew Bay for the tell-tale line against the sky. Each day they returned dispirited, almost as much by what they had witnessed on the way, as by the lack of a ship. Was there to be no let up in the calamity? The scenes of despair and deprivation seemed to her to have worsened. Droop-limbed skeletons of men – and women – hauled turf on their backs through the streets, once work only for beasts of burden. When she mentioned this at The Inn, they laughed at her naïveté.

‘There’s not an ass left in Westport that hasn’t been first flayed for the eightpence its pelt will bring, then its hindquarters eaten,’ a well-cushioned jobber jibed. ‘Now the peasants who sold them have to make asses of themselves!’

She was shocked at the indifference of the commercial classes to the plight of ‘the peasants’.

Nervous of everything, she kept the children close by and was cross with them if they wandered, terrified that she’d lose them. That they’d be swallowed in the hordes of the famished who filled the streets with the smell of death and the excrement of bodies forced to feed inwardly upon themselves.

Once she traipsed them with her to Croagh Patrick. They climbed to where they could look across the dotted archipelago of the bay, out past the Clare Island lighthouse. She could see no tall ships, only boats far out, maybe tobacco smugglers, or those ferrying the contraband Geneva, an alcoholic liquor flavoured with juniper and available from under the counter – if asked for – at The Inn.

They climbed higher for better vantage, Ellen straining her eyes against the gold and green of sun and sea. Here, on this age-old mountain, St Patrick had fasted for forty days and forty nights. ‘Those who worship the Sun shall go in misery … but we who worship Christ, the true Sun, will never perish.’ In the writing of his Confession the saint had denounced the sun and its worshippers. Now she prayed to the sun to bring them a ship. Sun-up or sun-down, it didn’t matter, as long as it came. To the west her eye caught a rib of white stone rising heavenwards against the bulk of the mountain. A ‘Famine wall’ going nowhere, built on the Relief Works to exact moral recompense from the starving stone-carriers. They in turn given ‘relief’; a few pence in pay, a handful of soup-tickets.

She remembered how on the last Sunday of summer, Reek Sunday, as it was widely known, the Clogdubh – the Black Bell of St Patrick – was brought there for weary pilgrims to kiss, for a penny. Black from the holy man pelting it at devils, they said. She had never kissed it. For tuppence, those afflicted with rheumatism might pass it three times around the body, for relief. Another superstition of the shackling kind that bred paupers to pay priests. Like the legends about the reek itself. Legends, she guessed, grown to feed misery and repentance, to keep the people out of the sun.

She thought of ascending the whole way – making the old pilgrimage, beseeching the high place where the tip of the mountain disappeared into the lower heavens, to send a ship. But what was it, anyway? Only a heap of piled-up rocks, only a mountain. And what could a mountain do? Still, she called the children and followed the path to the First Station. Seven times they shambled around the cairn of stones intoning seven Our Fathers, seven Hail Marys and one Creed. She wondered why once of everything wasn’t enough, why it had to be seven times.

Then she turned her back on St Patrick’s mountain, angry, yet disquieted by her rejection of it, and dragged them down the miles with her to Westport. Westport, relic of the anglicization of Ireland. A Plantation town of well-mannered malls, the canalized Carrowbeg outpouring the grief and suffering of its hapless inhabitants.

St Patrick and the Protestant Planters could have it between them.

5

Whether her anger had moved the sullen mountain, or whether it was merely favourable winds, the next morning produced a miracle. A ship out of Londonderry – the Jeanie Goodnight – had rounded Achill Island under cover of darkness and now sat at the quay: and she was Boston-bound. Word of the ship’s arrival had spread like wildfire, igniting all of Westport into frenzied quay-life once again. The Inn emptied.

Ellen left the children behind her in the room, admonishing them not to leave it. Wild with excitement, she threw off her shoes and ran bare-stockinged all the way to the office of Mr John Reid, Jun., the dress hiked up behind her like a billowing sail and with every stride storming Heaven that she wasn’t too late.

The quay was teeming with people. Would-be travellers clutched carpetbags to their breasts – food and their entire earthly possessions within. Many were young, single women, who vied for ground with barking agents and anxious excise men. While late-arriving jobbers had their own solution, jabbing at obstructive buttocks with their knob-handled cattle-sticks.

Already the ship agent’s door was mobbed, cries of ‘Amerikay!’ ascending at every turn. Call the damned at the Gates of Hell. Like it was their last hope.

It was her last hope. If they didn’t embark on this ship, who knew when another would come. She and her children would be fated to stay in Ireland. Her money would run out, and in time they would sink lower and lower, until they, too, ended up on scraps of pity and charity and the off-cuts of ass-meat. She lunged into the crowd, all thought of her gender put aside. Nor did the opposite gender give ground to her, unless she took it. Pushing and elbowing, she scrimmaged her way forward until she reached the front.

‘Mr Reid! Mr Reid!’ she shouted, money in her fist, shaking it above her head. ‘Passage for four to Boston!’ she beseeched.

At last he beckoned her forward, she banged down the money onto his desk.

Fifteen minutes later she left, four sailing tickets to Boston clenched like a prayer between her two hands.

Their passage was secured.

The children were overjoyed, Mary more restrained than the others, at the thought of leaving Katie behind. Ellen wondered if the silent girl really understood what all the excitement was about. Sometimes, you just didn’t know with her. But the girl clapped her hands, looking from one to the other of them, her hazel-brown eyes shining, her pert little nose twitching with delight.

Thrice daily, morning, noon, and at eventide, Ellen went to check on the Jeanie Goodnight lest the ship slip out again unexpectedly, just as she had ghosted into the western seaboard town.

Three days later they were headed out into the bay, Westport behind them in the mist, like a shaken shroud. She hated the place. Its workhouse which had taken Michael; the hordes of its hungry, clawing to get aboard the ship ahead of her, the lucky ones, their passage paid by land-clearing landlords.

Once aboard, she had changed her clothes, shaking the stench of Ireland out of them, then boiled them. As the Jeanie Goodnight threaded its way through the drumlin-humped islands, she was aware of the Reek to her left, the cursed mountain always looking down on them, whichever way you went, by land or by sea; watching, judging. She wouldn’t look at it directly. It was part of the Ireland of the past drawing away behind them. An Ireland of Famine; of vacant faces and outstretched hands – an island of beggars, no place for her and her children.

There they had been, she, Michael, all of them, back there in the mountains, waiting, year in year out, for the potatoes to grow. Beating their way down the road to the priest to give thanks, prostrating themselves, when they did grow; beating their breasts in contrition for imagined sins when they didn’t. Then, trudging over and back to Pakenham’s place to pay the rent, hoping he wouldn’t raise it on them when they had it, grovelling for clemency, citing ‘the better times to come’ when they hadn’t.

Always on their knees, giving thanks or pleading. They were to be pitied, the whole hopeless lot of them. It wasn’t the mountains of Maamtrasna that imprisoned them, or the watery arms of the Mask that landlocked them. It wasn’t even, she knew, the landlords and the priests. It was themselves. Going round in circles, beholden to the present and beholden to the past, with its old seafóideach customs, handed down from generation to generation. Tradition, woven around their lives from before they were born, like some giant web. She wanted to strip it all away from her now, never return. If it wasn’t for Michael and Katie back there on its bare-acred mountain, in its useless soil.

‘A Mhamaí …’ The tug at her sleeve startled her.

It was Mary. The child’s eyes, though dry, were blotched from rubbing. Mary would try to hide it from her that she still cried over Katie. That was her way. In the days they had waited for the ship, Ellen had talked to her and Patrick about the need to be strong; the child now beside her looked anything but. Though her first instinct was to take Mary in her arms, Ellen instead led her to the bow of the ship.

‘See, Mary! See out there beyond the horizon – the place where the sea meets the sky?’

Mary nodded.

‘Well, out there is America

‘Is it like Ireland?’ Mary interrupted.

‘No, Mary, it isn’t. America is a big and rich country not like Ireland at all.’

Mary fell silent. Ellen, sensing the child’s disappointment, pressed on. ‘It will be better than Ireland, Mary, I promise you it will be better. But we are going to have to be Americans. We must forget we are Irish. Leave all … all that behind us.’

Mary turned from looking out ahead, trying to see this land where they would be different people. ‘But, a Mhamaí –’

Ellen stopped her, gently. ‘Mary … you mustn’t call me that – “ a Mhamaí ” – any more. We are going to be Americans now. People don’t say that in America. From now on you must call me “Mother”!’

The child said nothing – only looked at her.

‘It’s all right,’ Ellen said, taking her by the shoulders. ‘Nothing’s changed. We’re still the same between us in English as in Irish,’ she smiled. ‘Do you understand?’

Mary once more looked out between the deepening sky and the widening ocean, trying to see beyond where they met. Out to this place, this America.

‘Yes … Mother,’ she answered, giving voice to the strange-sounding word – the wind from America holding it back in her throat, so that Ellen could scarcely catch it.

Out they tacked, past the Clare Island lighthouse, tall and solid-walled. Its white-painted watchtower, lofted heavenwards two hundred feet, would see them safely past Achill Sound. ‘A graveyard for ships,’ Lavelle had told her before she had left Boston. It was his place, Achill. This island, cut off from Ireland’s most westerly shore. ‘Achill – wanting to be in America,’ he always joked.

She hadn’t yet broached the subject of Lavelle with the children, except in a general fashion, like she had mentioned Peabody; both as people in Boston with whom she conducted business dealings. She would have to tell them more about Lavelle – that they were partners, but in business matters only. Albeit that she was fully conscious of his affection for her, and in turn regarded him highly, it was her intention never to remarry. She would be true to Michael to the grave. If, thereby, she was denying herself the tender comforts of marriage life, and a father’s guiding hand for her children, then so be it. That was the price to be paid of her troth to Michael.

An eddy of breeze swirling up from Achill Sound made her shiver slightly. She loosened then re-knotted the blue-green scarf Lavelle had given her at Christmas. She had four long weeks at sea in which to reaffirm her intentions.

The Jeanie Goodnight, a triple-masted emigrant barque, with burthen eight hundred tons, and a master and crew of nineteen, was constructed of the best oak and pine Canadian woods could yield. On her arrival at Westport she had disgorged four hundred tons of Indian corn, twelve hundred bags of the dreaded yellow meal; flour, Canadian timber and East Coast American potatoes. There had been a riot, the poor seeking to seize what supplies arrived with the ship. It was the only way they would get food, by taking it.

When Patrick raised the question of inferior food being shipped into the country crossing with superior food being shipped out, all she could say was, ‘It doesn’t make any more sense to me, Patrick, than it does to you. I don’t understand these things.’ It really didn’t matter what food there was, good or bad. The famished had scarcely a penny between them with which to buy it anyway.

Soon they had sailed beyond the reach of Achill Sound, leaving behind her last view of Ireland – disused lazy beds climbing towards the sky over Clew Bay.

The voyage was a good one, the elements favouring them so that the copper-fastened Jeanie Goodnight sat steady and proud in Atlantic waters. Ellen kept themselves to themselves. Their fellow passengers were a mixed lot. Above deck were the commercial Catholic classes – shopkeepers, grocers, middlemen – and those called ‘strong farmers’, taking what possessions they had, fleeing the sinking ship that was Ireland. There was too a good sprinkling of voyagers from Londonderry and the northern counties.