Полная версия

Plague Child

Most of the workers had drifted away to find other work, he told me. After the keel of the ship outside had been laid down, the money had run out. Three gentlemen had shares in the boat. When one had been imprisoned for debt, the others had refused to pay until they could replace the shareholder. Until the arguments between King and Parliament were settled, he said, all business was marooned, like the skeleton of the ship which was slowly beginning to rot.

I asked him who the sailors were who had stayed with Susannah that night.

‘Sailors?’ He shook his head. ‘Weren’t sailors. Boatman brought them from the City. They said they were friends of yours. Hoped they might find you here.’

‘Did you believe them?’

He spat and went to the window again. ‘Wouldn’t have them aboard ship,’ he said. ‘One looked like a soldier.’ He spat again. ‘Or had been. He had a long face. Wore a beaver hat. The other I wouldn’t like to argue with. Said they were helping you find your father.’

‘Matthew? What did you tell them?’

‘Same as I told the other man that came looking for him, soon after he vanished.’

‘What other man?’

For the first time he looked at me directly. ‘In trouble, are you?’

I said nothing.

He hesitated, then went on. ‘I told them and the other man that Matthew was looking for a berth on a boat to Hull, or maybe a coal boat back to Newcastle.’

‘Is that where he went?’

He looked at me searchingly, spat again, then moved some charts from a stool and told me to sit down. He took down a flask from the same shelf on which stood the bottle of London Treacle they gave me the day I burnt myself with pitch, and I remembered the strange dream of the old gentleman bending over me that day as I slept in this very room.

‘How’s your scar?’ he asked.

I showed him the discoloured, slightly puckered flesh. He looked at it almost approvingly as he shoved to one side of his desk drawings of ships that might be, or might never be, and poured a dark brown liquid from the flask.

‘You’ll have a few of those before you’re done.’

I coughed as I swallowed the fiery brown liquid and tears came to my eyes. This seemed to put him in better humour.

‘And a few of those.’

He swallowed what he said was the best Dutch brandy-wine, duty paid (a wink), poured himself another and stared out at the half-finished boat in the silent dock.

‘Matthew stood here, the day you went. He wanted to go down and say goodbye. He heard you shout “Father” and he very nearly went down then. But he was too frightened.’

‘Where did he go?’

He pointed at the river. ‘He went upstream, not down, the day after you left – the very next tide. I got him a berth in a barge. I heard him say he wanted to be dropped off somewhere between Maidenhead and Reading. I’ve no idea where he was going from there, but he reckoned it was a day’s travel, by the green road, whatever that means.’

I embraced him. ‘Thank you, thank you! You said there was another man came looking for Matthew. Just after he vanished. Who was that?’

The shipwright gave me something between a shake and a shudder. ‘I never seen him before, and I’m not very particular about seeing him again. Told me where to send knowledge of Matthew, but I never had no knowledge to send him, did I?’

During this he rummaged in a drawer amongst old charts and tidal tables until he unearthed a slip of paper. The hand was crabbed and uneven, with short, angry downstrokes that dug into the paper; the hand of a man who had learned to write later in life and with difficulty, and with many loops and flourishes designed to display his status. He had written: R. E. Esq., at Mr Black, Half Moon Court, Farringdon, London.

The shipwright did not know who R.E. Esq was, but said he had a scar on his face, drawing a line from cheek to neck, exactly as Matthew had done when he had warned me about the scarred man over the camp fire six years ago.

Before I was out of the door he was pouring himself another brandy. I was halfway down the steps when he shouted:

‘Wait! All that talk and I nearly forgot . . .’

Again he rummaged in a drawer, then another, muttering to himself before finally unearthing a coin. ‘Matthew said it was yours, not his.’

It touched me to the heart when I thought that my father, even in such a panic, and when he must have needed all the money he had, had left me what he could. ‘Mine?’

‘Belonged to thee. That’s what he said.’

Puzzled, I took the coin from him, turning it over and over, as if I could read some message from the inscriptions. But it was a silver half crown, like any other, showing the King on a charger.

Chapter 6

They – whoever they were – would find me if I stayed in Poplar. So I did what I judged they would not expect. Like Dick Whittington, I turned again, walking back towards the City.

I would find out who they were, the men who, I was convinced, had killed my mother. Try and find the answer to the questions that whirled endlessly in my head like so many angry bees. Why had Mr Black taken me on as an apprentice? What was his connection to the man with the scar?

The man who could answer these questions, or most of them, was Mr Black.

The wind was driving dark, scudding clouds over the marsh when I set off next morning, after spending a second night at Mother Banks’s. I reached the outskirts of the City at midday. There I stopped. I would not get far in my apprentice’s uniform, and the seaman’s jaunty scrap of a cap barely concealed my red hair.

Just inside the City I found the kind of market I needed. From Irish Mary at a second-hand clothing stall I bought thin britches – because they had bows that tied at the knee, which I fondly imagined to be the height of fashion – and traded my give-away apprentice’s boots for a pair of shoes with fancy buckles like those ‘worn at court’, she said. A leather jacket tempted me, and I drew out the coin Matthew had left for me. She bit it, saying it was not only a good one, but one of the first to be minted.

‘How can you tell that?’

‘See? On the rim there – the lys?’

Her long fingernail pointed to a tiny fleur-de-lys, above the King’s head. She said the mint mark showed that it was coined in 1625, the year of the King’s Coronation.

‘About as old as you are,’ she cackled.

An unaccountable shiver ran through me; the sort of shiver that used to make Susannah ask: ‘Has someone walked over thy grave, Tom?’

Matthew had told the shipwright it was mine and I took it back, turning it round and round between my fingers, feeling that perhaps it was a magic coin and, if I spent it, I would be spending part of my past. I reluctantly took off the expensive jacket, and put the coin back in my pocket. Instead I bought what she called a Joseph, perhaps after the coat of many colours, although these colours were those of various leather patches that held it together, larded with grease and other stains I did not care to question. At another stall I exchanged my apprentice’s knife for a saw-tooth dagger. The upper part of the blade was lined with teeth that would catch the tempered blade of any sword and snap it.

The City looked different. Cornhill was swept clean. In spite of drizzling rain, groups of scavengers were out in Poultry, throwing household filth, dead birds and a dead dog into their carts. They did not argue, as they usually did, that a pile of refuse was ‘over the line’ in the other’s ward, or, when the other cart was out of sight, dump it over the boundary. Planks were being laid so that coaches would not get stuck in the muddy streets. A group of men were arguing fiercely outside St Stephen, Walbrook, where the bells were ringing. I asked one man what o’clock it was and what was the service? He told me it was four of the clock and there was no service. They were practising the bells for the King.

‘The King?

I stared at him stupidly. ‘Do you not know? The King has set up a government with the Scots. He arrives tomorrow from Edinburgh to talk to Parliament.’

To talk to Parliament! I stood there, stunned. The King was going to listen to Parliamentary demands! I walked away in a dream. I felt that what Mr Ink had said was coming true, and we were on the brink of a new world.

It was beginning to grow dark, but it was too early to find Will, my drinking companion, in the Pot. I hoped to beg a bed from him. Once, when it had been too late to return to Half Moon Court after a heated debate, I had slept in his father’s tobacco warehouse. I made my way towards the red kites, which always dipped and soared above Smithfield in the evening, searching, like the poor, for what the butchers had thrown away. In Long Lane I stopped. When I ran from Half Moon Court, Mr Black had shouted that I was in great danger. Just words to entice me back? Or a genuine warning? I seemed to recall a note of real desperation in his voice. I still carried my apprentice’s uniform, rolled in a bundle. I turned it over and over in my hands, unable to admit to myself that the bond between us was quite broken.

From Half Moon Court came the sound of horses. A voice I did not recognise was shouting brusque commands.

A woman with a boy and girl running round her skirts came out of the market clutching a bloody bundle in a scarf, full of high spirits at finding their evening meal. The girl had a battered wooden toy and the boy tried to grab it. The girl ran from him into the street just as a Hackney hell-cart came out of Cloth Fair into Long Lane.

The boy stopped short, but the girl stood frozen in front of the approaching cart. The driver, who was riding one of the two horses, pulled frantically at the reins. The horse he was on responded but the other reared, dragging the coach forward at an angle towards the child. The child stared upwards at the rearing horse, wonder rather than fear on her face. The woman was screaming.

A man in the coach shouted, his voice cut off as he was thrown against the side. The flailing hooves were descending towards the child. Only then did she turn to run.

I flung my uniformed bundle at the horse’s head. The horse shied away, whinnying frantically, falling against the other horse, hooves coming down inches from the girl as I snatched her up.

I stood there holding her while the driver struggled to calm the panic-stricken horses. I was shaking, but she seemed unmoved.

‘Horse,’ she said, stretching her hand out to the animal the driver was preparing to remount.

‘Horse,’ I agreed, stroking her hair. ‘Horse.’

Her mother, sobbing with relief, was moving towards us when the curtain in the coach slid back. All I could see was the scar. A livid scar running from cheek to neck. The man had twisted round in his seat, and the scar seemed to be doing the cursing, swearing at me.

Petrified, I gripped the little girl to me. My hat had come off, and it was still light enough for him to see me. But he was righting himself, cursing and rubbing his head where he struck it.

He turned towards me. I glimpsed fine linen and eyes as cold as money. Before he could see my face I lifted the little girl high in the air, dandling her up and down in front of me to conceal my red hair. She squealed in delight.

‘Are you trying to get your children killed? One less mouth to feed?’

I felt all the fear and hatred that I had heard in my father’s voice when he had spoken of the man. And anger that there was not a trace of concern for the child or her mother. An almost uncontrollable urge filled me to pull him from the coach. Then the woman spoke:

‘I am sorry, sir. I am truly sorry. It is my fault.’

Hearing the beseeching, pleading note in her voice, taking all the blame when the coach was travelling so recklessly, I could stand it no longer. I handed her the child and walked up to the coach.

But he had turned away with a grudging satisfaction at her apology and was now shouting at the driver, who, with some difficulty, had quietened the horses. ‘Come on, come on, man! I must get to Westminster before dark.’

He shut the curtain. The driver scuttled for his whip, cracked it and the carriage lurched off. I stood there, staring after it. Although there was a chill in the evening air, my body crawled with sweat at how near I had come to giving myself away. There was a timid touch at my elbow. The woman was holding out the scarf, which wrapped the bloody remains she had scavenged. I felt a double pang: that she should offer me her supper, and that I could look as if I needed it. She whispered something to the little girl.

‘Thank you,’ the girl said.

I smiled, moved to gallantly sweep off my hat and bow, discovered the hat was not there, affected great surprise, which drew a giggle from the girl and a smile from the woman, and could not seem to find it although it lay in front of my eyes, which drew peals of laughter from the girl.

‘It’s there!’

‘Where?’

‘There!’

This welcome little game was interrupted by a familiar voice.

‘What’s going on?’

George had come out of Half Moon Court. He still had a plaster on his head where I had struck him, but his darting eyes seemed as sharp as ever. I turned away, retrieving my hat. The woman told him what had happened. All that seemed to concern him was that the coach and its occupant had gone. I moved to pick up my uniform, torn and muddied by the wheels of the coach. I felt his eyes on me, but then I heard Anne’s voice.

‘George, are you going?’

My heart lifted. If only I could speak to her before her father!

‘I must get my coat,’ George said. ‘It’s a chill evening.’

‘Please hurry!’

‘All right, all right,’ he muttered.

He gave me another curious look. I bent and picked up a rotting apple from the sewer, which seemed to satisfy him I was a beggar, for he went back into the court. Under the overhanging jetties it was darker and easy to follow him, keeping to the shadows of the opposite building. Although my new shoes leaked, they made less noise than the clumsy boots. Candles were lit in the house. The last of the light always came into my window in the evening, and I could see the edge of my mother’s Bible on the sill.

At least, I determined, I would take that away.

Anne came to the doorway. She wore a pale-blue, high-waisted dress which I knew to be her best, presumably for the benefit of the visitor. Over that she had put on an apron. She carried George’s coat. He seemed to take an interminable time putting it on, during which he shook his head gravely before finally coming to a decision to speak.

‘What has happened to Mr Black is God’s visitation on you, Miss Anne,’ he said.

She looked at him in terror. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I think you know,’ he said steadily.

‘Indeed I do not! Please go for the doctor.’

I stared up at the window of Mr Black’s bedroom. In the wavering candlelight I could just see Mrs Black passing restlessly by the bed, peering out of the window.

George stopped buttoning his coat, glanced up at the window, not speaking until Mrs Black had passed out of sight. ‘You let the devil out of the cellar,’ he said softly.

‘I did no such thing!’ Her voice was equally low, but sharp and contemptuous, as if it was the last thing in the world she would dream of doing.

‘I saw you.’

‘I came down when I heard the disturbance.’

‘I saw you going up.’

There was a trace of uncertainty in his voice which she leapt on. ‘You cannot have done. You make too much of yourself. Get the doctor!’

Perhaps he was lying and merely suspected. Or had seen something, but, groggy after my blow, could not be sure. At any rate, he began to move away reluctantly, and my heart went out to her for standing up to him.

All would have been well, but then she added bitterly: ‘You should have let him have a candle.’

She knew what she had said as soon as the words were out of her mouth. He stopped and turned very slowly. As he did so I caught the smile of satisfaction on his face. It vanished as he looked at her with grave concern.

‘How did you know about the candle?’

She gave a little moan. ‘Please go.’

‘Mr Black needs more than a doctor to cure him. We must root out the cause of the illness: your sin.’

He spoke so solemnly, so gravely, I had to struggle against the feeling that he was right, had been right all the time, and that the devil was within me. When George and Mr Black had first brought me here from Poplar, before the boat bumped against Blackfriars Stairs, had I not sworn a pact with him to be as evil as possible?

‘You must confess,’ George demanded.

She staggered. I thought she was going to faint.

‘I cannot tell my father – it would kill him!’

‘Then you must confess to God.’

‘Yes, yes. You will not tell my father?’

‘If you are good, child, and accept my guidance.’

She nodded perfunctorily, turning away. I could see she was on the edge of tears. ‘Please go now.’

He was insistent. ‘You will? Accept my guidance?’

‘Yes!’

He smiled. ‘God be praised! The sinner repenteth!’

He took her hands and began murmuring a prayer. At first she submitted, head bowed, but when she tried to take her hands away he only held them more tightly, murmuring away. Half a dozen times I nearly broke out of that doorway. Half a dozen times I forced myself back until suddenly I no longer cared whether he was pure good and I was pure evil. I jumped out.

‘Leave her! Leave her alone!’

Nothing George had said could have made his point better. For a moment I must have looked like some foul spirit coming out of the ground. Anne screamed and backed away to the door. George ran. ‘Anne!’ Mrs Black shouted from upstairs. ‘What is it? Has George gone for the doctor?’

There was no sign of him. ‘I’ll go,’ I said.

Guilt drove me: I felt that Mr Black’s illness was my fault. And breaking a bond is not just a matter of throwing away a uniform and selling boots. I went because I could not get out of my head it was no longer my job. Several times a year Mr Black had these strange attacks. He would stop what he was doing and stare at me like a blind man. Once, he dropped back on his chair, missed it, and fell to the floor. The first time I was very frightened, but Mrs Black drummed into me that when he had one of these attacks I must run and fetch Dr Chapman, for my master’s life depended on it.

The doctor practised near St Bartholomew’s in Little Britain but, luckily, was returning from a patient only two streets away. He was a bustling little man, of great good humour.

When I first met him I had told him I hated my hair; he offered to cup me for nothing, in the light of the discoveries of Mr Harvey, who declared that blood circulated and nourished everything. If enough was taken, he said, it might drain the colour from my hair. I thought he was serious and backed away hastily, at which he burst out into roars of laughter.

Now he said slyly, as we hurried back to Half Moon Court: ‘I like your court dress, Tom. Are you to be presented to the King tomorrow?’

He went upstairs laughing, but that soon died. I always knew from the sound of his voice how serious the attack was. Now his greeting and his banter dwindled almost immediately into silence. There was no sign of George or Anne. It was very quiet, apart from the murmurings of the doctor, and the occasional creaks when he moved across the floor above me. There was no chance of my confronting Mr Black, but I might get my Bible.

I opened the door to the kitchen, where a kettle was heating by the side of the fire. I crept to the bottom of the stairs; from there I could see that the door to Mr Black’s bedroom was closed. There was the faint clink of metal against a basin. I had watched Dr Chapman cup him once. After tightening a bandage round Mr Black’s arm he would warm a lancet in the candle flame and draw it across a bulging vein. After a spurt of blood there would be a steady flow. It would take about ten minutes.

I took a step or two up the stairs. A shadow fell across the small landing above. I glimpsed the edge of Mrs Black’s dress and pulled back against the wall. Never able to stand the blood-letting, she had gone into her own room. Anne was probably with her.

I stood indecisively. I could see straight through to the print shop, and beyond that to Mr Black’s small office. The door, normally locked, was open. Papers littered the writing desk and the floor around it. A chair had been knocked over. I took a candle from the kitchen and went past the printing press into the office. Mr Black must have been working here when he had the attack.

As I picked up the chair I saw it: a bound black accounts book, of the type Mr Black used to keep a note of deliveries of ink and paper, and sales of pamphlets. But on the cover of this one was inked a single letter T.

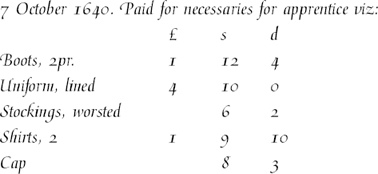

Whatever I hoped to see when I opened it, it was not dull accounts. But there they were in Mr Black’s neat hand, items of purchase and columns of figures.

I flicked through the pages rapidly. There was my life in Half Moon Court, from the cost of the watermen that had brought me here and the tutorials with Dr Gill, down to the very bread and cheese I had eaten, faithfully recorded right to the last halfpenny. I stopped as a word which seemed out of place with the others half-registered in the turning pages: portrait. Portrait?

I turned back, to see an entry whose amount dwarfed all the others.

8 August 1635. Paid to P. Lely. Portrait in oils & frame. £20-0-0.

I had had no portrait done. The very idea was laughable. Only people at court had their pictures painted. No. That was not quite true. Each Lord Mayor had his portrait painted and hung in the Guildhall. I went very still.

The summer of 1635 I had taken a message to the clerk in the Guildhall and been told to wait for a reply. While I was in the waiting room a young man wandered in. His smock and hands were daubed with paint. He spoke with a thick Dutch accent and said the Mayor had gone out to a meeting, and he too was waiting for him.

He pushed my face to one side so he could see the profile and grunted something in Dutch. He said he was tired of painting old men who wanted to look young and dashing, and as an exercise he would really like someone young and dashing to sketch.

I was flattered and amazed by the incredible speed with which he sketched. By the time the clerk came with the reply, and to say that the Mayor was ready again, the painter had caught me like a bird in flight. A grin. A sulk when I grew bored with him. In profile. Staring with wide eyes straight out of the paper.

As the charcoal flew across the paper he grunted, ‘The eyes you have. The nose. Everything but the hair.’

‘What do you mean?’

He seemed too absorbed in the next sketch to answer. ‘Turn. No no – the other way!’

I begged him for a sketch but he said he needed them all. ‘Perhaps the painting you may one day see, mmm?’

He smiled, patting me on the cheek, leaving traces of charcoal and paint which I left there until they disappeared.

Peter – that was his name. I stared at the account book: P. Lely. Peter Lely. Perhaps Mr Black had commissioned him to do a portrait of himself. No. No printer could afford it, and if he could he would surely hang it prominently. Somebody had paid for a picture of me. But who? Why? And where was it?

I heard sounds upstairs; the doctor’s deep voice and Mrs Black’s low murmuring answer. Quickly I riffled through the remaining pages. A folded piece of paper, which I supposed was used as a marker, flew out of the book. I picked it up and placed it on the table. There was nothing of interest in the rest of the accounts, but there was a whole new section at the end. Mr Black had turned the book upside down to start the section on the last page. It was a cross between a diary and a tutor’s report on my progress, or lack of it.