Полная версия

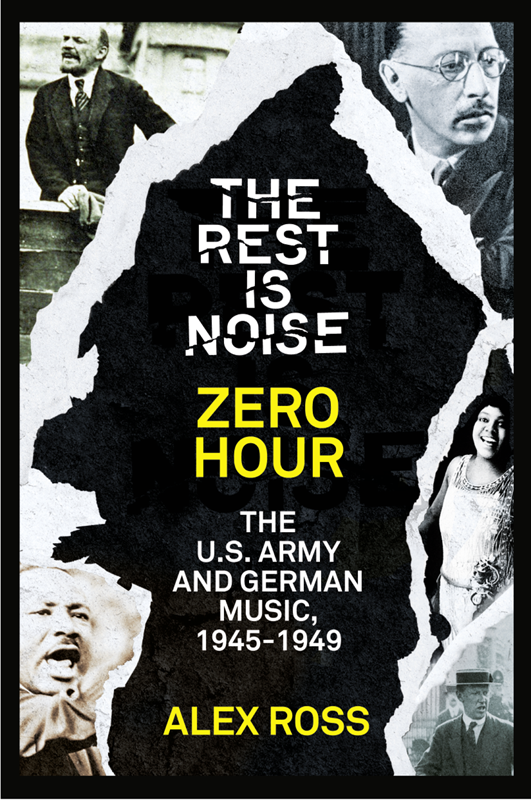

The Rest Is Noise Series: Zero Hour: The U.S. Army and German Music, 1945–1949

This is a chapter from Alex Ross’s groundbreaking history of 20th century classical music, The Rest is Noise.

It is released as a special stand-alone ebook to celebrate a year-long festival at the Southbank Centre, inspired by the book. The festival consists of a series of themed concerts. Read this chapter if you’re attending concerts in the episode

Post-War World: Making a Break with the Past

Alex Ross, music critic for the New Yorker, is the recipient of numerous awards for his work, including an Arts and Letters Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Belmont Prize in Germany and a MacArthur Fellowship. The Rest is Noise was his first book and garnered huge critical acclaim and a number of awards, including the Guardian First Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is also the author of Listen to This.

ZERO HOUR

The U.S. Army and German Music, 1945–1949

From The Rest Is Noise by Alex Ross

Contents

Zero Hour

Notes

Suggested Listening and Reading

Copyright

About the Publisher

10

ZERO HOUR

The U.S. Army and German Music, 1945–1949

On April 30, 1945, the day of Hitler’s suicide, “zero hour” in modern German history, the 103rd Infantry and Tenth Armored divisions of the U.S. Army took possession of the Alpine resort of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which the war had hardly touched. Two hundred Allied bombers had been poised to lay waste to the town and its environs, but the strike was called off at the behest of a surrendering German officer.

Early in the morning a security detachment turned in to the driveway of a Garmisch villa, intending to use it as a command post. When the senior officer, Lieutenant Milton Weiss, went inside the house, an old man came downstairs to meet him. “I am Richard Strauss,” he said, “the composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome.” Strauss studied the soldier’s face for signs of sympathy. Weiss, who had played piano at Jewish resorts in the Catskills, nodded his head in recognition. Strauss went on to recount his experiences in the war, pointedly mentioning the tribulations of his Jewish relatives. Weiss chose to install his post elsewhere.

At 11:00 a.m. on the same day, a squad of jeeps came up the drive, these led by Major John Kramers, of the 103rd Infantry Division’s military-government branch. Kramers told the family that they had fifteen minutes to evacuate. Strauss walked out to the major’s jeep, holding documents that declared him to be an honorary citizen of Morgantown, West Virginia, together with part of the manuscript of Rosenkavalier. “I am Richard Strauss, the composer,” he said. Kramers’s face lit up; he was a Strauss fan. An “Off Limits” sign was placed on the lawn.

In the days that followed, Strauss posed for photographs, played the Rosenkavalier waltzes on the piano, and smiled bemusedly as soldiers inspected his statue of Beethoven and asked who it was. “If they ask one more time,” he muttered, “I’m telling them it’s Hitler’s father.”

All over Europe, young veterans were emerging from the rubble of the war into adulthood. Among them were several future leaders of the postwar musical scene, and they would be indelibly marked by what they had experienced in adolescence. Karlheinz Stockhausen was the son of a spiritually tortured Nazi Party member who went to the eastern front and never returned. His mother was confined for many years to a sanatorium, then killed in the Nazi euthanasia program. By the age of sixteen, Stockhausen was working in a mobile hospital behind the western front, where he tried to revive soldiers who had fallen victim to Allied incendiary bombs. “I would try to find an opening in the mouth area for a straw,” he recalled, “in order to pour some liquid into these men, whose bodies were still moving, but there was only a yellow ball-like mass where the face should have been.” On a given day Stockhausen and his comrades would haul thirty or forty corpses into churches that had been converted into morgues.

Hans Werner Henze trained as a radio operator for Panzer battalions and spent the first part of 1945 riding aimlessly around the ruined landscape. Bernd Alois Zimmermann was drafted at the age of twenty-one and served in Poland, France, and Russia. Luciano Berio was conscripted into the army of Mussolini’s Republic of Salò and nearly blew off his right hand with a gun that he did not know how to use. Iannis Xenakis joined the Greek Communist resistance, fighting not only the Germans but also the British, who, in an early demonstration of Cold War Realpolitik, made common cause with local Fascists when they occupied the country. At the end of 1944 a British shell landed on a building where Xenakis was hiding; after watching a comrade’s brains splatter against a wall, he passed out and awoke to find that his left eye and part of his face were gone.

In July 1945, the young English composer Benjamin Britten, who had just scored a triumph in London with his opera Peter Grimes, accompanied the violinist Yehudi Menuhin on a brief tour of defeated Germany. The two men visited the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen and performed for a crowd of former inmates. Stupefied by what he saw, Britten decided to write a cycle of songs on the Holy Sonnets of John Donne, the most spiritually scouring poetry he could find. On August 6 he set to music Sonnet 14, which begins, “Batter my heart, three person’d God.” Earlier the same day, the first operational atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. There is an eerie coincidence here, for J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the American nuclear program, cherished the same Donne poem, and evidently had it in mind when he gave the site of the first atomic test the name Trinity.

On August 19, Britten finished his cycle by setting Donne’s sonnet “Death be not proud.” The singer declaims the words “And death shall be no more” on a rising scale; fixates for nine long beats on the word “Death”; and finally, over a clanging dominant-tonic cadence, thunders, “Thou shalt die.”

In 1945 Germany was a primitive society such as Europe had not known since the Middle Ages. The former citizens of Hitler’s Thousand-Year Reich were living a hand-to-mouth existence, scavenging for food, drinking from drainpipes, cooking over wood fires, living in the basements of destroyed houses or in hand-built trailers and cabins. In 1948 the glamorous young American musician Leonard Bernstein arrived in Munich to conduct a concert and reported back home: “The people starve, struggle, rob, beg for bread. Wages are often paid in cigarettes. Tipping is all in cigarettes. It is all misery.”

Millions of prisoners of war lived in camps; millions more roamed the roads, having fled the Soviet occupation in the east or been expelled from neighboring countries by policies of ethnic cleansing. No sooner had Hitler made his exit than Stalin replaced him as a threat. The collected might of Anglo-American industry, which had been used to obliterate one German city after another, now became the engine of reconstruction. Germany would be reinvented as a democratic, American-style society, a bulwark against the Soviets. Part of that grand plan was a cultural policy of denazification and reeducation, which would have a decisive effect on postwar music.

Germany and Austria broke apart into American, British, French, and Soviet zones. The head of the American occupation—the Office of Military Government, United States, or OMGUS—was an evenhanded, incorruptible, staggeringly efficient man named Lucius Clay. What made Clay interesting was that his background combined strict West Point training with a whiff of New Deal idealism; in the Army Corps of Engineers he had coordinated building projects with the WPA, and an early evaluation had called him “inclined to be bolshevistic.” The military governor wanted to reshape and lift up Germany as Roosevelt had reshaped and lifted up America. At a conference in Berchtesgaden, near Hitler’s old redoubt, Clay said, “We are trying to free the German mind and to make his heart value that freedom so greatly that it will beat and die for that freedom and for no other purpose.”

The project of freeing the German mind went by the name “re-orientation.” The term originated in the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force, which was led by Brigadier General Robert McClure. Psychological warfare meant the pursuit of military ends by nonmilitary means, and in the case of music it meant the promotion of jazz, American composition, international contemporary music, and other sounds that could be used to degrade the concept of Aryan cultural supremacy.

One key member of General McClure’s staff was the émigré Russian composer Nicolas Nabokov. “He’s hep on music and tells the Krauts how to go about it,” one military man said of this ebullient, charming, and slippery personality. Back in the twenties and early thirties, Nabokov had belonged to Serge Diaghilev’s cadre of composers at the Ballets Russes. His music was relatively negligible, his ability to cultivate high-level social and political connections positively virtuosic; in the postwar era he would show a Zelig-like ability to appear in the middle of any cultural imbroglio.

With the coming of OMGUS, Psychological Warfare evolved into Information Control, taking responsibility for all cultural activity in the occupied areas. In keeping with the re orientation paradigm, military and civilian experts were brought in to guide extant organizations and encourage new, forward-looking ones. Many in Information Control’s Music Branches had thorough training and a progressive outlook on contemporary music. Two of the brightest were stationed in Bavaria, the birthplace of the Nazi Party. John Evarts, who served there from 1946 on, had taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Schoenberg’s pupil Heinrich Jalowetz was on the faculty. Joining Evarts in 1948 was the Mississippi-born pianist Carlos Moseley, who had studied alongside Leonard Bernstein at Koussevitzky’s music school in the Berkshires.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.