Полная версия

Blood, Tears and Folly: An Objective Look at World War II

1

BRITANNIA RULES THE WAVES

For the bread that you eat and the biscuits you nibble,

The sweets that you suck and the joints that you carve,

They are brought to you daily by all us Big Steamers

And if any one hinders our coming you’ll starve!

Rudyard Kipling, ‘Big Steamers’

It is not in human nature to enshrine a poor view of our own performance, to court unnecessary trouble or to wish for poverty. Myths are therefore created to bolster our confidence and well-being in a hostile world. They also conceal impending danger. Having temporized in the face of the aggressions of the European dictators, Britain went to war in 1939 without recognizing its declining status and pretending that, with the Empire still intact, the price of freedom would not be bankruptcy.

In 1939 the British saw themselves as a seafaring nation and a great maritime power, but the two do not always go hand in hand. In order to understand the Royal Navy’s difficult role in the Atlantic in the Second World War, it is necessary to return to the past and separate reality from a tangled skein of myth. Later in the book similar brief excursions will give historical perspective on the performance of the army and the air force, both in Britain and in the other main wartime powers.

After the Renaissance it was Portuguese and Spanish sailors who led the great explorations over the far horizons, while the English concentrated upon defending the coastline that had insulated them from the rest of Europe for centuries. By the middle of the sixteenth century Spain and Portugal had established outposts in America, Asia and Africa, and their ships carried warriors, administrators and freight around the globe in 2,000-ton ships made in India from teak and in Cuba from Brazilian hardwoods. But when England’s shores were threatened, small and less mighty vessels made from English oak and imported timber, sailed by skilful, intrepid and often lawless Englishmen, came out to fight. Using fireships, and helped by storms and by the hunger and sickness on the Spanish vessels, Francis Drake and his men decimated the mighty Armada.

Such dazzling victories have prevented a proper appreciation of the maritime achievements of our rivals. While English privateers were receiving royal commendations for preying upon the Spanish galleons from the New World, the Dutch and the Portuguese were fighting on the high seas for rule of the places from which the gold, spices and other riches came.

The Dutch were an authentic seafaring race. They had always dominated the North Sea herring fishing, right on England’s doorstep, and traded in the Baltic. Their merchant ships carried cargoes for the whole world. By the early 1600s one estimate said that of Europe’s 25,000 seagoing ships at least 14,000 were Dutch. The English sailor Sir Walter Raleigh noted that a Dutch ship of 200 tons could carry freight more cheaply than an English ship ‘by reason he hath but nine or ten mariners and we nearer thirty’.

In 1688 the Dutch King William of Orange was invited to take the English throne. Dutch power at sea was subordinated to English admirals. At this time England had 100 ships of the line, the Dutch 66 and France 120. England’s maritime struggles with the Netherlands ended, and France – England’s greatest rival and potential enemy – was outnumbered at sea. The French were not a seafaring race, they were a land power. Their overseas colonies and trade were not vital to France’s existence. Neither were exports vital to England, where until the 1780s the economy depended almost entirely upon agriculture, with exports bringing only about 10 per cent of national income.

The Dutch king’s ascent to the English throne was the sort of luck that foreigners saw as cunning. It came at exactly the right moment for England. From this time onwards the French seldom deployed more than half of the Royal Navy’s first-line strength. Soon the industrial revolution was producing wealth enough for Britain to do whatever it pleased. But that wealth depended upon the sea lanes, and the Royal Navy had to change from a strategy of harassing and plundering to escorting and protecting merchant shipping. It was not easy to adapt to the shepherd’s role. The Royal Navy was by tradition wolflike; its speciality had always been making sudden raids upon the unprepared. ‘It could be fairly said,’ wrote the naval historian Jacques Mordal, ‘that with the exception of Trafalgar, the greatest successes of the British navy were against ships at their moorings.’1 Damme, Sluys, La Hougue, the Nile, Copenhagen, Navarino and Vigo Bay were all such encounters. So were the actions against the French navy in 1940.

It was Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo that gave the Royal Navy mastery of the seas. France, Holland and Spain, weakened by years of war, conceded primacy to the Royal Navy. Britain became the first world power in history as the machines of the industrial revolution processed raw materials from distant parts of the world and sent them back as manufactured goods. Machinery and cheap cotton goods were the source of great profits; so were shipping, banking, insurance, investment and all the commercial services that followed Britain’s naval dominance. The British invested abroad while Britain’s own industrial base became old, underfinanced, neglected and badly managed, so that by the mid-nineteenth century the quality of more and more British exports was overtaken by her rivals. Manufacturing shrank, and well before the end of the century service industries became Britain’s most important source of income. The progeny of the invincible iron masters dwindled into investment bankers and insurance men.

To cement the nineteenth century’s Pax Britannica Britain handed to France and the Netherlands possessions in the Caribbean, removed protective tariffs and preached a policy of free trade, even in the face of prohibitive tariffs against British goods and produce. The Royal Navy fought pirates and slave traders, and most of the world’s great powers were content to allow Britain to become the international policeman, especially in a century in which restless civil populations repeatedly threatened revolution against the existing order at home.

The British fleet showed the flag to the peoples of the Empire in five continents and was a symbol of peace and stability. Well-behaved children of the middle classes and workers too were regularly dressed in sailor costumes like those the British ratings wore.2 But appearances were deceptive. The Royal Navy was unprepared for battle against a modern enemy.

As the nineteenth century ended the importance of the Royal Navy was diminishing. Population growth, and efficient railway networks, meant that armies were becoming more important than navies. The new-found strength that industrialization, much of it financed by Britain, had given to other nations ended their willingness to let Britain play policeman. Although in 1883 more than half of the world’s battleships belonged to the Royal Navy, by 1897 only two of every five were British3 and countries such as Argentina, Chile, Japan and the United States had navies which challenged the Royal Navy’s local strength.

Since the time of Nelson the cost of the Royal Navy had increased to a point where it tested Britain’s resources. Nelson’s ships were cheap to build and simple to repair. Needing no fuel, sailing ships had virtually unlimited range, and by buying food locally cruises could be extended for months and even years. But the coming of steam engines, screw propellers and turbines, together with the improving technology of guns, meant supplying overseas bases with coal, ammunition and all the tools and spares needed for emergencies. Full repairs and maintenance could only be done in well-equipped shipyards. A more pressing problem was the steeply increasing cost of the more complex armoured warships. In 1895 the battleship HMS Majestic cost a million pounds sterling but HMS King George in 1910 cost almost double that.

The time had come for Britain’s world role, its methods and its ships, to be totally revised. An alliance with Japan, and the recognition that cultural ties made war with the USA unthinkable, released ships from the Pacific stations. An alliance with France released ships from the Mediterranean so that the Royal Navy could concentrate virtually its entire sea-power in home waters facing the Germans. Germany had been identified as the most potent threat, and anxiety produced a climate in which talk of war was in the air.

The German navy

Germany dominated Europe. Prussia, where in 1870 nearly 45 per cent of the population was under twenty years of age, dominated Germany. Otto von Bismarck (nominally chancellor but virtually dictator) had remained good friends with Russia while winning for his sovereign quick military victories over Denmark and Austria-Hungary. Then to the surprise of all the world he inflicted a terrible defeat upon France. Reparations – money the French had to pay for losing the war of 1870 – made Germany rich, universal conscription made her armies large, and Krupp’s incomparable guns made them mighty. After the victory over the French, the German king became an emperor and, to ensure France’s total humiliation, he was crowned in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. Bismarck now had everything he wanted. He looked for stability and was ready to concede the seas to Britain.

But in 1888 a vain and excitable young emperor inherited the German throne. Wilhelm II of Hohenzollern had very different ideas. ‘There is only one master in the country, and I am he.’ He sacked Bismarck, favoured friendship with Austria-Hungary instead of Russia, gave artillery and encouragement to the Boers who were fighting the British army in southern Africa (a conflict that has been called Britain’s Vietnam), spoke of a sinister-sounding Weltpolitik and, in an atmosphere of vociferous anti-British feeling, began to build his Kaiserliche Marine.

Despite Britain’s small population4 and declining economic performance, the strategic use of sea-power had given the British the most extensive empire the world had ever seen. Yet although a large proportion of the world lived under the union flag, Britain had nothing like the wealth and military power to hold on to the vast areas coloured red on the maps. Tiny garrisons and a few administrators convinced millions of natives to abide by the rules of a faraway monarch. The army’s strategic value was in guarding the naval bases where the Royal Navy’s world-ranging ships were victualled, coaled or oiled. Luckily for Britain, its military power was not seriously challenged for many years. Only when the Boers in South Africa erupted was Britain’s tenuous grip on its territories clearly demonstrated.

The German army on the other hand had shown its might and skills again and again, and having seen their army march into Paris in 1870 the German navy itched to test itself against the British. With almost unlimited funds at his disposal Rear-Admiral Alfred Tirpitz was to build for the Kaiser the sort of fleet that would be needed to challenge the Royal Navy. In anticipation of this moment, German naval officers more and more frequently held up their glasses and toasted ‘Der Tag!’ – the day of reckoning.

Admiral Tirpitz claimed to be unaware that his preparations were aimed at war with Britain. ‘Politics are your affair,’ he told the Foreign Ministry, ‘I build ships.’5 And as if to prove his point he sent his daughters to study at the Cheltenham Ladies’ College in England.

The British were alarmed by the prospect of an enlarged German navy. Still more worrying for them was the rise in German trade, which went from £365 million in 1894 to £610 million in 1904, with a consequent increase in German merchant ship tonnage of 234 per cent. In fact Britain’s foreign markets were suffering more from American exporters than from German ones but – still smarting from Germany’s pro-Boer stance – the British resented the Germans, while Anglo-American relations on personal and diplomatic levels remained very good.

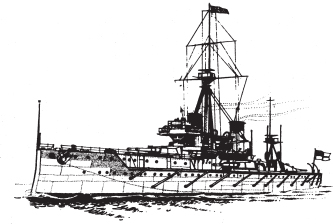

In December 1904 Britain’s new first sea lord, Admiral Fisher, started planning his new all-big-gun battleships. Although naval architects in Italy, America and Japan had all predicted the coming of a super-warship, this one was so revolutionary in design that it gave its name to a new category of battleship.

The big hull had spent only one hundred days on the stocks when King Edward VII launched HMS Dreadnought on a chilly February day in 1906. He wore the full dress uniform of an admiral of the fleet, which Britain’s monarchs favoured for such ceremonials, when he swung the bottle of Australian wine against her hull. The bottle bounced and failed to break and he needed a second attempt before the wine flowed, and the great warship went creaking and groaning down the slipway into the water.

She was completed in record time: one year and a day. The use of the rotary turbine, instead of big upright pistons, made her profile more compact and thus better armoured. According to one admiral the bowels of previous battleships were uncomfortable:

When steaming at full speed in a man of war fitted with reciprocating engines, the engine room was always a glorified snipe marsh; water lay on the floor plates and was splashed about everywhere; the officers often were clad in oilskins to avoid being wetted to the skin. The water was necessary to keep the bearings cool. Further the noise was deafening; so much so that telephones were useless and even voice pipes of doubtful value … In the Dreadnought, when steaming at full speed, it was only possible to tell that the engines were working, and not stopped, by looking at certain gauges. The whole engine room was as clean and dry as if the ship was lying at anchor, and not the faintest hum could be heard.6

FIGURE 1

HMS Dreadnought

Gunnery was also changed. Ships armed with many short-range guns – exemplified by the 100-gun Victory – were no match for ships which could fire salvos of very heavy shells at long range. The big gun had proved itself. For the Americans sinking the Spanish ships at Santiago and Manila Bay, for the Japanese destroying the Russian fleet at Tsushima, the big gun had proved the decisive weapon. ‘Dreadnoughts’ – as all the new type of capital ships were now to be called – would have speed enough to force or decline a naval action. Furthermore the long-range gun would offset the threat of the torpedo; a sophisticated weapon that, wielded by dashing little vessels, threatened the future of the expensive warships.

The introduction of the Dreadnought design was a denial of Britain’s decline. It signalled that Britain had started to build its navy afresh, and that its sea-power could be equalled only by those who kept pace with the building programme. Almost overnight Admiral Tirpitz found his 15-battleship fleet completely outclassed. The Kaiser responded at once. SMS Nassau, the first of Germany’s Dreadnoughts, was ready for action by March 1908. On paper the German ships seemed inferior in design to the Dreadnoughts of the Royal Navy – for instance Nassau employed reciprocating engines and had 11-inch guns compared with HMS Dreadnought’s 12-inch ones. But the Nassau’s guns had a high muzzle-velocity, which gave a flat trajectory for better aim and penetration. The ship’s interior was very cramped, but top-quality steel was used as armour. Her small ‘honeycomb-cell’ watertight compartments made her extremely difficult to sink; a feature of most German warships.

The big new German ships provided the Berlin planners with an additional problem. The 61-mile-long Kiel Canal was essential to German naval strategy, for it eliminated a long and hazardous journey around Denmark, and the need for a separate Baltic Fleet to face the threat of Russian sea-power. But the Kiel locks had been built for smaller warships; there was no way that the Germans could squeeze a ship the size of a Dreadnought through the Canal.

Churchill – first lord of the Admiralty

In 1911, when the 36-year-old Winston Churchill was appointed first lord of the Admiralty (the minister responsible for the Royal Navy), he was appalled to find his Whitehall offices deserted, and ordered that there be always officers on duty. On the wall behind his desk he put a case, with folding doors which opened to reveal a map on which the positions of the German fleet were constantly updated. Churchill started each day with a study of that map.

Churchill revolutionized the navy. His principal adviser was the controversial Sir John Arbuthnot Fisher, who predicted with astounding accuracy that war against Germany would begin on 21 October 1914 (when widening of the Kiel Canal for the new German battleships was due to be completed). The Royal Navy did not welcome Churchill’s ideas. When he wanted to create a naval war staff, they told him they did not want a special class of officer professing to be more brainy than the rest. One naval historian summed up the attitude of the admirals: ‘cleverness was middle class or Bohemian, and engines were for the lower orders’.7

Churchill forced his reforms upon the navy. He created the Royal Naval Air Service. Even more importantly, he changed the navy’s filthy coal-burning ships, with their time-consuming bunkering procedures, to the quick convenience of oil-burning vessels with 40 per cent more fuel endurance. As industry in Britain was built upon coal but had no access to oil, this entailed creating an oil company – British Petroleum – and extensive storage facilities for the imported oil. He ordered five 25-knot oil-burning battleships – Queen Elizabeth, Warspite, Barham, Valiant and Malaya – and equipped them with the world’s first 15-inch guns. Normally a prototype for such a gun would have been built and tested, but rather than waste a year or more, Churchill put the guns straight into production so that the ships could be ready as soon as possible.

Britain’s need for naval alliances had dragged her into making an agreement with France that should war come Britain would send an army to help defend her. This was a dramatic change in Britain’s centuries-old policy of staying out of mainland Europe. Cautious voices pointed out that no matter what such an expeditionary force might achieve in France, Britain remained vulnerable to foreign fleets. It was a small offshore island dependent upon imported food, seaborne trade and now oil from faraway countries instead of home-produced coal. The extensive British Empire was still largely controlled by bureaucrats in London. Defeated at sea, Britain would be severed from its Empire, impoverished and starved into submission.

The First World War

To what extent Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm was set upon war with England in 1914 is still difficult to assess. If there was one man who, by every sort of lie, deceit and stupidity, deliberately pushed the world into this tragic war, that man was Count Leopold ‘Poldi’ Berchtold, Austrian foreign minister. But the German Kaiser stood firmly behind him and showed no reluctance to start fighting.

Bringing recollections of Fisher’s warning, elements of the Royal Navy were at Kiel, celebrating the opening of the newly widened Canal, when news came of the assassination at Sarajevo. A few weeks later Europe was at war. It was also significant that Britain’s widely distributed warships were told ‘Commence hostilities against Germany’ by means of the new device of wireless.

Germany had 13 Dreadnoughts (with ten more being built); Britain had 24 (with 13 more under construction, five of which were of the new improved Queen Elizabeth class). However, this superiority has to be seen against Britain’s worldwide commitments and Germany’s more limited ones.

Britain’s Admiral Fisher had gloated that the Germans would never be able to match the Royal Navy because of the untold millions it would cost to widen the Kiel Canal and deepen all the German harbours and approaches. The Germans had willingly completed this mammoth task. The British on the other hand had refused to build new docks and so could not build a ship with a beam greater than 90 feet. Sir Eustace Tennyson-d’Eyncourt (Britain’s director of naval construction) was later to say that with wider beam, ‘designs on the same length and draught could have embodied more fighting qualities, such as armour, armament, greater stability in case of damage, and improved underwater protection’.

The Germans built docks to suit the ships, rather than ships to fit the docks. With greater beam, the German ships also had thicker armour. Furthermore the German decision to build a short-range navy meant that less space was required for fuel and crews. More watertight compartments could be provided, which made German warships difficult to sink. This could not be said of ships of the Royal Navy.

The Royal Navy’s planners would not listen to the specialists and experts and continuously rejected innovations for the big ships. While British optical instrument companies were building precise range-finders (with up to 30 feet between lenses) for foreign customers, the Admiralty was content with 9 feet separation. When Parsons, the company founded by the inventor and manufacturer of turbine engines, suggested changing over to the small-tube boilers that worked so well in German ships, the Admiralty turned them down. The triple gun-turrets that had proved excellent on Russian and Italian ships were resisted until the 1920s.

The German navy welcomed innovation. After a serious fire in the Seydlitz during the Dogger Bank engagement of 1915 they designed anti-flash doors so that flash from a shell hitting a turret could not ignite the magazine. On Royal Navy ships cordite charges in the lift between magazine and turret were left exposed, as was the cordite handling room at the bottom of the lift, and the magazine remained open during action. This weakness was aggravated by the way that British warships were vulnerable to ‘plunging fire’ that brought shells down upon the decks and turrets. Typically turrets would have 9-inch-thick side armour and 3-inch-thick tops. This deficiency would continue to plague the Royal Navy in the Second World War.

Churchill’s gamble with his 15-inch guns paid off, but the smaller German guns had the advantage of high muzzle-velocity. The Royal Navy knew that its armour-piercing shells broke up on oblique impact with armour but had not solved this problem by the time the First World War began. Only eight Royal Navy ships had director firing (as against gunners choosing and aiming at their own targets), while it was standard in the German navy. The superior light-transmission of German optics gave them better range-finders, and German mines and torpedoes were more sophisticated and more reliable. The Royal Navy neglected these weapons, regarding them as a last resort for inferior navies. It was a view open to drastic revision when HMS Audacious, a new Dreadnought, sank after collision with a single German mine soon after hostilities began.

As warfare became more dependent upon technology German superiority in chemistry, metallurgy and engineering became more apparent. The German educational system was ahead of Britain. In 1863 England and Wales had 11,000 pupils in secondary education: Prussia with a smaller population had 63,000. And Prussia provided not only Gymnasien for the study of ‘humanities’ but Realschulen to provide equally good secondary education in science and ‘modern studies’.8 The French scholar and historian Joseph Ernest Renan provided an epilogue to the Franco-Prussian War by saying it was a victory of the German schoolmaster. The education of both officers and ratings, coupled to the strong German predilection for detailed planning and testing, produced a formidable navy. Its signalling techniques and night-fighting equipment were superior to those of the British and this superiority was to continue throughout the war. Churchill warned in 1914 that it would be highly dangerous to consider that British ships were superior or even equal as fighting machines to those of Germany.