Полная версия

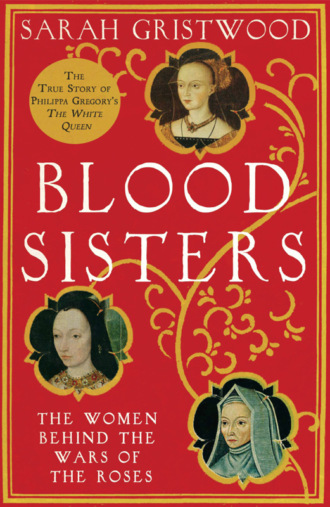

Blood Sisters: The Hidden Lives of the Women Behind the Wars of the Roses

The business of their lives was power; their sons and husbands the currency; the stark events of these times worthy of Greek tragedy. Cecily Neville had to come to terms with the fact that her son Edward IV had ordered the execution of his brother George, Duke of Clarence, and the suspicion that her other son Richard III had murdered his nephews. Elizabeth Woodville is supposed to have sent her daughters to make merry at Richard III’s court while knowing that he had murdered her sons, those same Princes in the Tower. Elizabeth of York, as the decisive battle of Bosworth unfolded, could only await the results of what would prove a fight to the death between the man some say she had incestuously loved – her uncle Richard III – and the man she would in the end marry, Henry VII.

The second half of the fifteenth century is alive with female energy, yet the lives of the last Plantagenet women remain relatively unexplored. The events of this turbulent age are usually described in terms of men, under a patriarchal assumption as easy as that which saw Margaret Beaufort give up her own blood right to the throne in favour of her son Henry; or passed the heiress Anne Neville from one royal family to the other as though she were as insentient an object as any other piece of property.

Of the seven women who form the backbone of this book, the majority have already been the subject of at least one biographical study. The aim of this work, however, is to interweave these women’s individual stories, to trace the connections between them – connections which sometimes ran counter to the allegiances established by their men – and to demonstrate the way the patterns of their lives often echoed each other. It tries to understand their daily reality: to see what these women saw and heard, read, smelt, even tasted. The bruised feel of velvet under the fingertip, or the silken muzzle of a hunting dog. The discomfort of furred ceremonial robes on a scorching day: a girl’s ability to lose herself in reading a romantic story.

The stamping feet of the ‘maid that came out of Spain’ and danced before Elizabeth of York, and the roughened hands of Mariona, the laundrywoman listed in Marguerite of Anjou’s accounts who kept the queen’s personal linen clean. The tales of Guinevere and Lancelot, popularised in these very years by a man who knew these women; along with the ideal of the virginal saints whose lives they studied so devotedly. To ignore these things and to focus too exclusively on the wild roller coaster of military and political events results in a distorted picture, stripped of the context of daily problems and pleasures.

The attempt to tell the story of these years through women is beset with difficulties, not least the patchy nature of the source material. To insist that the women were equal players with the men, on the same stage, is to run the risk of claiming more than the known facts can support. The profound difference between their ideas and those of the modern world must first be acknowledged; but so too, conversely, must recognisable emotions – Elizabeth of York’s frantic desire to find a place in the world, Margaret Beaufort’s obsessive love for her son. It is the only way we can imagine how it felt to be flung abruptly to the top of Fortune’s wheel and then back down again. And though the tactics of the battlefield are not the subject of this book, each one meant gain or loss for wives, daughters and mothers whose destiny would be decided, and perhaps unthinkably altered, in an arena they were not allowed even to enter.

The Tudor wives of only a few decades later have a much higher profile, and yet the stories of these earlier figures are even more dramatic. These women should be a legend, a byword. Perhaps their time is coming. The months between hardback and paperback publication of this book have seen the first distant rumbles of change – word that Philippa Gregory’s novels about the women of the Cousins’ War are to become a BBC series, and the furore of interest surrounding the question of whether the bones unearthed in a Leicester car park would prove to be those of Richard III. It seems appropriate that the answer could come through the strain of mitochondrial DNA passed down only in the female line, from Richard’s mother Cecily.

In a time not only of terror but of opportunity, the actions of the women forged in this furnace would ultimately prove to matter as much as the battlefields on which cousin fought cousin.2 Their alliances and ambitions helped get a new world under way. They were the mothers and midwives if not actually of modern England, then certainly of the Tudor dynasty.

ONE

Fatal Marriage

O peers of England, shameful is this league,

Fatal this marriage, cancelling your fame

Henry VI Part 2, 1.1

It was no way for a queen to enter her new country, unceremoniously carried ashore as though she were a piece of baggage – least of all a queen who planned to make her mark. The Cock John, the ship that brought Marguerite of Anjou across the Channel, had been blown off course and so battered by storms as to have lost both its masts. She arrived, as her new husband Henry VI put it in a letter, ‘sick of ye labour and indisposition of ye sea’. Small wonder that the Marquess of Suffolk, the English peer sent to escort her, had to carry the seasick fifteen-year-old ashore.1 The people of Portchester in Hampshire, trying gallantly to provide a royal welcome, had heaped carpets on the beach where the chilly April waves clawed and rattled at the pebbles, but Marguerite’s first shaky steps on English soil took her no further than a nearby cottage, where she fainted. From there she was carried to a local convent to be cared for.

This would be the woman whom Shakespeare, in Henry VI Part 3, famously dubbed the ‘she-wolf’ of France, her ‘tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide’. The Italian-born chronicler Polydore Vergil,2 by contrast, would look back on her as ‘imbued with a high courage above the nature of her sex … a woman of sufficient forecast, very desirous of renown, full of policy, counsel, comely behaviour, and all manly qualities’. But then Vergil was writing for the Tudor monarch Henry VII, sprung of Lancastrian stock, and he would naturally wish to praise the wife of the last Lancastrian king, the woman who had fought so hard for the Lancastrian cause. Few queens of England have so divided opinion; few have suffered more from the propaganda of their enemies.

Marguerite of Anjou was niece by marriage to the French king Charles VII, her own father, René, having been described as a man of many crowns but no kingdoms. He claimed the thrones of Naples, Sicily, Jerusalem and Hungary as well as the duchy of Anjou; titles so empty, however, that early in the 1440s he had settled in France, his brother-in-law’s territory. At the beginning of 1444 the English suggested a truce in the seemingly endless conflict between France and England known as the Hundred Years War; the arrangement would be cemented by a French bride for England’s young king, Henry VI. Unwilling to commit his own daughters, Charles had proffered Marguerite. Many royal and aristocratic marriages were made to seal a peace deal with an enemy, the youthful bride a passive potential victim. But in this case, the deal-making was particularly edgy.

In the hope of ending the long hostilities the mild-mannered Henry VI – so unfitting a son, many thought, to Henry V, the hero of Agincourt – had not only agreed to take his bride virtually without dowry but to cede the territories of Anjou and Maine, which the English had long occupied. This concession would be deeply unpopular among his subjects. Nor did the thunder and lightning that had greeted Marguerite’s arrival augur well to contemporary observers.

The new queen had been ill since setting out from Paris several weeks before. She progressed slowly towards the French coast, distributing Lenten alms and making propitiatory offerings at each church where she heard mass, dining with dignitaries and taking leave of her relations one by one along the way. But gradually, in the days after her arrival England, she recovered her health in a series of convents, amid the sounds and scents of Church ritual with all their reassuring familiarity. On 10 April 1445 at Southampton, one ‘Master Francisco, the Queen’s physician’ was paid 69s 2d ‘for divers aromatic confections, particularly and specially purchased by him, and privately made into medicine for the preservation of the health of the said lady’.

If Suffolk’s first concern had been to find medical attention for Marguerite, his second was to summon a London dressmaker to attend her before the English nobility caught sight of her shabby clothes: ‘to fetch Margaret Chamberlayne, tyre maker, to be conducted into the presence of our lady, the Queen … and for going and returning [from London to Southampton], the said Margaret Chamberlaune was paid there by gift of the Queen, on the 15th of April, 20s.’ Among the various complaints the English were preparing to make of their new queen, one would be her poverty.

Before Marguerite’s party set out towards the capital there was time for something a little more courtly, if one Italian contemporary, writing to the Duchess of Milan three years later, is to be believed. An Englishman had told him that when the queen landed in England the king had secretly taken her a letter, having first dressed himself as a squire: ‘While the queen read the letter the king took stock of her,3 saying that a woman may be seen very well when she reads a letter, and the queen never found out it was the king because she was so engrossed in reading the letter, and she never looked at the king in his squire’s dress, who remained on his knees all the time.’ It was the same trick that Henry VIII would play on Anne of Cleves almost a century later – a game from the continental tradition of chivalry.4

Henry VI, if the Milanese correspondent is to be believed, saw ‘a most handsome woman, though somewhat dark’ – and not, the Milanese tactfully assured his duchess, ‘so beautiful as your Serenity’. At the French court Marguerite had already acquitted herself well enough to win an admirer in the courtly tradition, Pierre de Brezé, to carry her colours at the joust; and to allow the Burgundian chronicler Barante to write that she ‘was already renowned in France for her beauty and wit and her lofty spirit of courage’. The beauty conventionally attributed to queens features in the scene where Shakespeare’s Marguerite first meets Henry VI: it was the lofty spirit that, in the years ahead, was to prove the difficulty. Vergil too wrote that Marguerite exceeded others of her time ‘as well in beauty as wisdom’; and though it is not easy to guess real looks from the conventions of medieval portraiture, it is hard not to read determination and self-will in the swelling brow and prominent nose that are evident in images of Marguerite of Anjou – in particular the medallion by Pietro di Milano.

The royal couple met officially five days after Marguerite had landed, and had their marriage formalised just over a week later in Titchfield Abbey. The first meeting failed to reveal either the dangerous milkiness in the man, or the capacity for violence in the young woman. But the first of the problems they would face was – as Marguerite moved towards London – spelt out in the very festivities.

Her impoverished father had at least persuaded the clergy of Anjou to provide funds for a white satin wedding dress embroidered with silver and gold marguerites; and to buy violet and crimson cloth of gold and 120 pelts of white fur to edge her robes. As her party approached the city she was met at Blackheath by Henry’s uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, with five hundred of his retainers and conducted to his luxurious riverside ‘pleasaunce’ at Greenwich. Gloucester had in fact opposed the marriage, seeing no advantage in it for England.

Marguerite’s entry into London on 28 May, after resting a night at the Tower, was all that it should have been. A coronet of ‘gold rich pearls and precious stones’ had been placed on the bride’s head, nineteen chariots of ladies and their gentlewomen accompanied her, and the conduits ran with wine white and red. The livery companies turned out in splendid blue robes with red hoods, while the council had ordered the inspection of roofs along the way, anticipating that eager crowds would climb on to them to see the new queen pass by.

The surviving documentation details a truly royal provision of luxury goods for Marguerite’s welcome. A letter from the king to his treasurer orders up ‘such things as our right entirely Well-beloved Wife the Queen must necessarily have for the Solemnity of her Coronation’. They included a pectoral of gold embellished with rubies, pearls and diamonds; a safe conduct for two Scotsmen and their sixteen servants, ‘with their gold and silver in bars and wallets’; a present of £10 each to five minstrels of the King of Sicily (the nominal title of Marguerite’s father) ‘who lately came to England to witness the state and grand solemnity on the day of the Queen’s coronation’; and 20 marks reward to one William Flour of London, goldsmith, ‘because the said Lord the King stayed in the house of the said William on the day that Queen Margaret, his consort, set out from the Tower’.

The ceremonies were ‘royally and worthily held’, the cost reckoned at an exorbitant £5500. All the same, Marguerite had had to pawn her silver plate at Rouen to pay her sailors’ wages; and as details of the marriage deal began to leak out, the English would feel justified in complaining that they had bought ‘a queen not worth ten marks’. In the years ahead, they would discover they had a queen who – for better or worse – would try to rewrite the rules, and indeed the whole royal story.

As Marguerite rode into her new capital, the pageantry with which she was greeted spelt out her duty. It was hoped that through her ‘grace and high benignity’:

Twixt the realms two, England and France

Peace shall approach, rest and unite,

Mars set aside, with all his cruelty …

This was a weight of expectation placed on many a foreign royal bride. Earlier in the fifteenth century the Frenchwoman Christine de Pizan had written in The Treasury (or, Treasure) of the City of Ladies that women, being by nature ‘more gentle and circumspect’, could be the best means of pacifying men: ‘Queens and princesses have greatly benefitted this world by bringing about peace between enemies, between princes and their barons, or between rebellious subjects and their lords.’ After all, the Queen of Heaven, Mary, interceded for sinners. Marguerite would be neither the first nor the last to find herself uncomfortably placed between the needs of her adopted country and that of her birth. The Hundred Years War had been a conflict of extraordinary bitterness. This bitterness Marguerite, by her very presence as a living symbol, was supposed to soothe; but it was a position of terrifying responsibility.

Her kinsman the Duke of Orléans wrote that Marguerite seemed as if ‘formed by Heaven to supply her royal husband the qualities which he required in order to become a great king’. But the English expectations of a queen were not those of a Frenchman, necessarily. Marguerite’s mother, Isabelle of Lorraine, had run the family affairs while René of Anjou spent long years away on campaign or in captivity. Her grandmother, Yolande of Aragon, in whose care she spent many of her formative years, had acted as regent for her eldest son, Marguerite’s uncle; and she had been one of the chief promoters of Joan of Arc, who had helped sweep the French Dauphin to victory against the English. Those English, by contrast, expected their queens to take a more passive role. Uncomfortable memories still lingered of Edward II’s wife Isabella, little more than a century before: the ‘she-wolf of France’, as Marguerite too would be dubbed, who was accused of having murdered her husband to take power with her lover. Had Marguerite’s new husband been a strong king, the memories might never have surfaced – but Henry showed neither inclination nor ability for the role he was called on to play.

Henry VI had succeeded while in his cradle, and had grown up a titular king under the influence of his older male relatives. Perhaps that had taught him to equate kingship with passivity. For although Henry had now reached adulthood he still, at twenty-three, showed no aptitude for the reins of government. There has always been debate over what, if anything, was actually wrong with Henry. Some contemporaries describe him as both personable and scholarly; others suggest he may have been simple-minded, or had inherited a streak of insanity. But what is certain is that he was notably pious, notably prudish – described by a papal envoy as more like a monk than a king – and seemed reluctant to take any kind of decision or lead. He was the last man on earth, in other words, to rule what was already a turbulent country. At the end of Henry IV Part 2 Shakespeare vividly dramatises the moment at which the new Henry V, this Henry’s father, moves from irresponsible princedom to the harsh realities of kingship. There was, however, no sign of Henry VI reaching a similar maturity. It was a situation which left Marguerite herself to confront the challenges of monarchy.

It is difficult to conjure up a picture of Marguerite or her husband in the first few years of their marriage. Anything written about them later is coloured by hindsight, and the early days of Marguerite’s career tend to be lost in the urgent clamour of events just ahead. But there is no reason to doubt that her expectation was that of a normal queenship, albeit more active than the English were accustomed to see. Though her husband’s exchequer may have been depleted, though English manners might not compare to those across the Channel, her life must at first have been one of pleasant indulgence.

Christine de Pizan gives a vivid picture of life for a lady at the top of the social tree. ‘The princess or great lady awaking in the morning from sleep finds herself lying in her bed between soft, smooth sheets, surrounded by rich luxury, with every possible bodily comfort, and ladies and maids-in-waiting at hand to run to her if she sighs ever so slightly, ready on bended knee to provide service or obey orders at her word.’ The long list of estates granted to Marguerite as part of her dower entitlement forms an evocative litany:

To be had, held and kept of the said Consort of Henry, all the appointed Castles, Honours, Towns, Domains, Manors, Wapentaches, Bales, county estates, sites of France, carriages, landed farms, renewed yearly, the lands, houses, possessions and other things promised, with all their members and dependencies, together with the lands of the Military, Ecclesiastic advocacies, Abbotcies, Priories, Deaneries, Colleges, Capellaries, singing academies, Hospitals, and of other religious houses, by wards, marriages, reliefs, food, iron, merchandize, liberties, free customs, franchise, royalties, fees of honour … forests, chaises, parks, woods, meadows, fields, pastures, warrens, vivaries, ponds, fish waters, mills, mulberry trees, fig trees …

It is the same genial picture of a queen’s life that can be seen in a tapestry that may have been commissioned for Marguerite’s wedding – there are Ms woven into the horses’ bridles, and marguerites, her personal symbol, are sported by the ladies. It depicts a hunting scene bedecked with flowers and foliage, the ladies in their furred gowns, hawk on wrist, wearing the characteristic headdress of the time, a roll of jewelled and decorated fabric peaking down over the brow and rising behind the head. Hunting, with ‘boating on the river’, dancing and ‘meandering’ in the garden were all recreations allowed by Christine de Pizan in a day otherwise devoted to the tasks of governance (if relevant), religious duties and charity. Visiting the poor and sick, ‘touching them and gently comforting them’, as she wrote, sounds much like the work of modern royalty. ‘For the poor feel especially comforted and prefer the kind word, the visit, and the attention of the great and powerful personage over anything else.’ Letters show Marguerite asking the Archbishop of Canterbury to treat ‘a poor widow’ with ‘tenderness and favour’; and seeking alms for two other ‘poor creatures and of virtuous conversation’.

But Marguerite had been brought up to believe that queenship went beyond simple Christian charity.5 Not only did she have the example of her mother and grandmother, but her father was one of the century’s leading exponents of the chivalric tradition, obsessed with that great fantasy of the age, the Arthurian legends. Indeed, when Thomas Malory wrote his English version of the tales, the Morte d’Arthur, completed in 1470, his portrayal of Queen Guinevere may have been influenced by Marguerite. It may have been on the occasion of Marguerite’s betrothal that René organised a tournament with knights dressed up as Round Table heroes and a wooden castle named after Sir Lancelot’s Joyeuse Garde. A bound volume of Arthurian romances was presented to the bride.

René was the author not only of a widely translated book on the perfect management of the tournament, but also of the achingly romantic Livre de Coeur de L’Amour Epris. He may have illustrated it, too; and if so, it has been suggested that his figure of Hope – who repeatedly saves the hero – may have been modelled on Marguerite. Queens in the Arthurian and other legends of chivalry were not only active but sometimes ambiguous creatures. Ceremonious consorts and arbiters of behaviour, they were also capable of dramatic and sometimes destructive action: it was Guinevere who brought down Camelot.

The two visions of queenship came together in the Shrewsbury – or Talbot – Book, a wedding present to Marguerite from John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. Although one of England’s most renowned military commanders, he would not play much part in the political tussles ahead. On the illuminated title page, Henry and Marguerite are seated crowned and hand in hand, her purple mantle fastened with bands of gold and jewels, the blue background painted with gold stars. At her feet kneels Talbot, presenting his book which she graciously accepts, the faintest hint of a smile lurking under her red-gold hair. All around are exquisite depictions of the daisy, her symbol. The image is at once benign and stately, an idealised picture of monarchy – for all that the facing page, tracing Henry VI’s genealogical claim to be king of France as well as of England, hints at political controversy. An anthology of Arthurian and other romances, poems and manuals of chivalry, the book also includes Christine de Pizan’s treatise on the art of warfare and one on the art of government – a guide not only to conducting one’s emotional life but also to running a country.

Henry had had his palaces refurbished for his bride – the queen’s apartments must have fallen out of use in his minority. Marguerite employed a large household and paid them handsomely, exploiting all the financial opportunities open to a queen to enable her to do so. Regulations for a queen’s household drawn up in the year of her arrival listed sixty-six positions, including a countess as senior lady with her own staff, a chamberlain, three chaplains, three carvers, a secretary, a personal gardener, pages of the beds and of the bakery, two launderers and various squires. Less than ten years later, the council had to suggest that the size of the queen’s household should be cut down to 120. She had, however, brought no relations and few French attendants with her, something which had been a problem with previous consorts. But what at first looked like a blessing meant that she would attach herself to new English advisers, ardently and unwisely.

On the journey from France Marguerite had learned to trust her escort Suffolk – the pre-eminent noble whom the Burgundian chronicler Georges Chastellain called England’s ‘second king’. She never saw any reason to change her mind – or to hide her feelings. Suffolk for his part, perhaps from a mixture of genuine admiration and intelligent politics, flattered and encouraged the young queen, even writing courtly verses playing on her name, the marguerite or daisy: