Полная версия

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed

But there has to be some attempt to define the term ‘thriller’, a term used as loosely in the past as ‘noir’ is today (‘Tartan Noir’, ‘Scandi Noir’, etc.) to describe an important segment of that exotic fruit which is generally known as crime fiction. Whether it matters a jot to the reader who simply wants to be entertained is debatable, but again, it probably does. Crime fiction is a recognised genre, just as horror, science fiction, romance, fantasy, westerns and supernatural are all genres of popular fiction and genres tend to have dedicated followers.

The idea of genre fiction evolved in the late nineteenth century and blossomed in the Thirties with the advent of cheaper, paperback books with crime fiction among the first instantly identifiable genres thanks to the famous green covers used by Penguins and logos such as the Collins Crime Club’s ‘gunman’. Dedicated readers were steered to genres they liked and genre readers appreciated the guidance – though they did not want to read the same book again, they did want more of the same.

Within a genre as big as crime fiction, which could be described as a broad church (albeit an unholy one) readers tended to specialise often to a slightly frightening degree. There are those who only read spy stories (and some who only read spy stories set in Berlin), those who only read the Sherlock Holmes canon, those who refuse point blank to read anything written after 1945, those who only want to read about serial killers, those who always prefer the private eye novel, those who disparage the amateur sleuth preferring police detectives, and these days there are those naturally light-hearted optimistic readers of nothing but Scandinavian crime fiction.

Thankfully only a few crime fiction readers go as far as some science fiction fans and attend conventions dressed as their favourite fictional heroes but all like the security of identifiable categories and so some attempt must be made to define the terms used in this book.

As a recognisable genre, the thriller is certainly as old if not older than the detective story which, casually ignoring the interests of students of eighteenth-century literature and languages other than English, is generally dated from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841. With reluctance, the honours could also go to America, with James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy (1821) and The Last of the Mohicans (1826) for the earliest examples of the spy thriller and the adventure thriller.

Already the dissection of the term ‘thriller’ has begun, yet by the time the British had flexed their writing muscles things were becoming clearer. Both Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883) and Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885), published in the same decade in which Sherlock Holmes took his first bow, were fully-formed adventure thrillers. They were adventure stories which thrilled and distinctly different from the detective story, which could of course be thrilling but in a different, perhaps more cerebral, way. If that was not confusing enough, the 1890s saw the early days of the spy novel – albeit in the shape of a string of xenophobic potboilers which revelled in the fear of an invasion of England by Russia, France, or even Germany.2 They were certainly meant to be thrilling, if not hysterical, but a quality mark was soon achieved with Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands (1903) and the work of John Buchan, seen by many as the Godfather of the quintessential British thriller, although he preferred the term ‘shocker’ presumably in the sense that his stories were electrifying rather than revolting.

When the Golden Age of the English detective story dawned, it suddenly seemed important that the thriller was publicly differentiated from the novel of detection which offered readers ‘fair play’ clues to the solution of the mystery, usually a murder. At least it seemed important to the writers of detective stories, who saw themselves as, if not quite an elite, then certainly a literary step up on the purveyors of potboilers and shockers.

The Golden Age can be dated, very crudely, as the period between the two world wars, beginning with the early novels of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers (when it actually ended is still a matter of some debate – an often interminable and sometimes heated debate). Although a boom time for detective stories, it was also a boom time for spy thrillers. Donald McCormick in his Who’s Who in Spy Fiction (1977) claims that the years between 1914 and 1939 were the most prolific period of the spy thriller, the public’s appetite having been whetted by the First World War and real or imagined German spy-scares. ‘The spy story became a habit rather than a cult’ was his polite way of saying that this was definitely not a Golden Age for the thriller. Names such as Edgar Wallace, E. Phillips Oppenheim, Sydney Horler and Francis Beeding (Beeding’s books were publicised under the banner ‘Breathless Beeding’ or ‘Sit up with …’ after a review in The Times had declared that Beeding was an author whose books made ‘readers sit up [all night] until the book is finished’) are now mostly found in reference books rather than on the spines of books on shelves, whereas certain luminaries of the Golden Age of detective fiction, such as Christie, Sayers, Margery Allingham, Anthony Berkeley and John Dickson Carr are still known and respected and, more importantly, in print somewhere.3

Back in the day though, the fact of the matter was that the Oppenheims and Breathless Beedings et al were the bigger sellers. Edgar Wallace’s publishers once claimed him to be the author of a quarter of all the books read in Britain (which even by publishing standards of hype is pretty extreme) and they were to inspire in various ways, often unintended, a new generation of thriller writers. In 1936, a debut novel, The Dark Frontier, arrived without much fanfare marking the start of the writing career of Eric Ambler, who was later to admit that he had great fun writing a parody of an E. Phillips Oppenheim hero.4 Two decades later, the eagle-eyed reader of a certain age could spot certain Oppenheim traits in another new arrival, James Bond. In fact, the reader didn’t have to be that eagle-eyed.

The question of what was a thriller, and how seriously it should be taken, seemed to exercise the minds of the writers of detective stories and members of the elite Detection Club, confident in the superiority of their craft, rather than the thriller writers themselves.

One writer closely associated with the Golden Age, though happy to experiment beyond the confines of the detective story, was Margery Allingham. In 1931, Allingham wrote an article for The Bookfinder Illustrated succinctly entitled ‘Thriller!’ trying to explain the different categories then evident in crime fiction. It was a remarkably good and fair analysis of the then current crime scene, identifying five types (and one sub-type) which made up the family tree of the ‘thriller’, which were:

Murder Puzzle Stories – which could be sub-divided into (a) ‘Novels with murder plots’ by writers ‘who take murder in their stride’ (such as Anthony Berkeley), and (b) ‘Pure puzzles’ such as those by Freeman Wills Crofts;

Stout Fellows – the brave British adventurer or secret agent, usually square-jawed and later to be known as the ‘Clubland hero’ type (as written by John Buchan);

Pirates and Gunmen – the adventurers and gangsters as found in the books of American Francis Coe and the prolific Edgar Wallace;

Serious Murder – novels such as Malice Aforethought by Francis Iles (Anthony Berkeley) which Allingham put ‘in the same class as Crime and Punishment’;

High Adventures in Civilised Settings – crime stories ‘without impossibilities and improbabilities’ for which she cited Dorothy L. Sayers as an example.

Whether Dorothy L. Sayers was pleased with this somewhat lofty and isolated categorisation is not recorded, but it is likely that she bridled at being lumped, even in a specialised category, in the general genre of thrillers. She was crime fiction reviewer for the Sunday Times in the years 1933–5 and was not slow off the mark to say that a novel she did not approve of had ‘been reduced to the thriller class’. Responding to a claim, real or imagined, that she had been ‘harsh and high hat’ about thrillers, she claimed to hail them ‘with cries of joy when they displayed the least touch of originality’, whenever she found one that is, which seemed to be rarely and she clearly felt the detective story the purer form. (This in turn provoked the very successful thriller writer Sydney Horler, creator of ‘stout fellow’ hero Tiger Standish, to remark rather acidly that Miss Sayers ‘spent several hours a day watching the detective story as though expecting something terrific to happen’.)5

In fairness, during her time as the Sunday Times critic, Sayers did attempt to provide a working definition of what a ‘thriller’ was and how it differed from the (in her opinion) far superior detective story. Indeed, she had three goes at doing so, which suggests the lady might have been protesting a little too much.

In June 1933 she suggested: ‘Some readers prefer to be thrilled by the puzzle and others to be puzzled by the thrills.’ She refined this in January 1934 to: ‘The difference between thriller and detective story is one of emphasis. Agitating events occur in both, but in the thriller our cry is “What comes next?” – in the detective story “What came first?”. The one we cannot guess; the other we can, if the author gives us a chance.’

Now Sayers believed in writing detective stories to a set of rules which gave the reader the chance, if they were clever enough, of guessing the solution to the mystery/problem posed before the author revealed the solution. She did not realise that there were readers out there who did not want the author to give them a chance, they just wanted to be thrilled however outrageous and implausible the story.

Sayers had a third go, in her Sunday Times column in March 1935, where she defined the thriller as something where ‘the elements of horror, suspense, and excitement are more prominent than that of logical deduction’. By that time an intelligent woman such as Sayers must have realised that the fair-play, by-the-rules detective story as an intellectual game was running out of steam and that other types of crime fiction were taking over. She herself effectively retired from crime writing after 1937.

Margery Allingham, who by her own set of definitions wrote most types of thriller, continued writing until her death in 1966 and kept a watchful eye on developments in the genre as a whole. In 1958 she was still wary of the superior status given to the detective story noting that ‘In this century there is a cult of the crime story as distinct from any other adventure story (thriller) – mainly read by people ill in bed.’6 Allingham’s gentle analysis was that the detective story had been an intellectual exercise, whereas the thriller had included adventure stories, almost modern fairy stories – by which she presumably meant Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. Now there was the crime story (in which she included the works of Georges Simenon and John Creasey) and the mystery story, a loose term which covered everything from the Gothic to the picaresque. In 1965, shortly before her death, like Sayers she predicted that the mystery story was ‘going out’ and would be replaced by the novel of suspense.

To further confuse matters, in 2002 in The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction compiled by Mike Ashley (one of the most respected anthologists in the business) Ashley excluded thrillers from his truly mammoth work on the grounds that ‘whilst some crime fiction may also be classed as a thriller, not all thrillers are crime fiction’. For his purposes, Ashley defines crime fiction as a book which involves the breaking and enforcement of the law, which is fair enough, but then he also excludes spy stories and novels of espionage – on the grounds that they constitute such a large field they deserve a study in their own right and even though spying usually involves breaking someone’s laws.

Even excluding thrillers and spy stories, as well as stories involving the supernatural or psychic detectives and anything labelled ‘suspense’ or ‘mystery’ (when describing the mood rather than content of a story), and then only dealing with authors writing since WWII, Ashley’s splendid encyclopedia weighs in at almost 800 pages.

Does any of this soul-searching by people in the business (writers, editors, reviewers) over terminology really matter? Because the field of crime fiction, or what the Victorians would have called ‘sensational fiction’, is now so large – so popular – it probably does, at least if one is trying to make a point about a particular aspect or time period.

To keep it simple, let us say that the overall genre of crime fiction encompasses crime novels (which contain danger, a puzzle or a mystery centred on an individual or individuals, the outcome of which is resolved by more or less lawful means by characters who are usually law-abiding citizens or officers of the state) and thrillers where the perceived threat is to a larger group of people, a nation or a society and a solution is reached by heroic action by individuals taking action outside the law, usually having to deal with extreme physical conditions or an approaching deadline.

Paraphrasing Dorothy L. Sayers, in the crime novel it is what happened in the past (who did the murder? what motive did the murderer have? how did a particular cast of characters happen to come together?) which is important; in the thriller it is what is going to happen next.

A good dictionary will define a thriller as a book depicting crime, mystery, or espionage in an atmosphere of excitement and suspense, which could, of course, also define the crime novel – accepting that espionage is a crime, or it certainly is if you are caught. So perhaps, to quote Sayers again, it is all a question of emphasis. In the crime novel the emphasis is on the crime and its consequences. In the thriller the emphasis is on thwarting or escaping the crime or its consequences and the thriller usually requires a conspiracy rather than a crime.

P. G. Wodehouse is reputed to have called readers of thrillers ‘an impatient race’ as they long ‘to get on with the rough stuff’ and rough stuff, or action, is certainly more predominant in the thriller, often taking place in a hostile environment – at sea, under the sea, in the Arctic, or under a pitiless desert sun, sometimes cliff-hanging from the edge of a precipice. In keeping with Edgar Wallace’s ‘pirate stories in modern dress’ description (of which Margery Allingham would have approved – she was keen on pirates and treasure hunts), the exotic foreign location became a popular trait of the British thriller. More than that, it became a major component and though it would be too simplistic to say that crime novels happened indoors whilst thrillers happened outdoors, the concentration on action and ‘rough stuff’ thrills did often require a large, open-air canvas.

If the key building blocks of crime fiction are: plot, characters, setting, pace, suspense and humour (the latter may come as a surprise, but there is a long tradition of humour in British crime writing going back to the days of Wilkie Collins), then one can logically assign large blocks of plot, character, and suspense and smaller characteristics of setting, pace, and humour to the crime novel whereas the thriller’s foundation might be huge blocks of plot, setting, and pace, with smaller proportions of bricks devoted to characters and suspense and sometimes no humour at all. (Ian Fleming disapproved of the use of humour in thrillers, though many other writers found room for a wise-cracking hero.)

Once again, it comes down to a question of emphasis.

For the period under review here – 1953 to 1975 in Britain – our basic division of crime fiction into crime novel and thriller is a starting point only. Any assessment of crime fiction over the period 1993 to 2015, for example, would certainly require a different schema and to cover the entire history of crime writing just in Britain would produce a family tree with so many sprigs and branches it would resemble a Plantagenet claim to the throne.

Such an exercise would be an interesting challenge, but this is not the place. Even so, we must divide our sub-genres into sub-sub-genres, but hopefully not too many. If we can accept that the crime novel is an identifiable entity, and that we know one when we read one, then it is reasonably safe to assume that we can all recognise Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express as a crime novel, but Ian Fleming’s From Russia, with Love, which involves at least two murders on the Orient Express, as something else – it’s a thriller.

In another example of compare-and-contrast, 1954 saw the publication of two novels which were both initially billed by their publishers as ‘adventures’. The Strange Land by Hammond Innes had a lone hero figure in an exotic location (Morocco) struggling with a shipwreck, arid desert and mountainous terrain. Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming had a lone hero in an exotic location (America and the Caribbean) battling gangsters and communists as well as Voodoo and sharks. Both were clearly thrillers, but different types of thriller. The Innes was an adventure thriller, for want of a better term, and the Fleming was a spy thriller, albeit featuring a hero who did little actual spying and who acted more as a secret policeman,7 and not a particularly secret one at that.

Ten years later, that distinction was redundant as a new, more realistic type of spy story began to appear. Live and Let Die may have been one sort of spy thriller but The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was obviously of a different ilk.

For the purpose of this survey, the novels under discussion – all thrillers – can be counted as adventure thrillers (for example, the work of Hammond Innes and Alistair MacLean), and, following the suggestion of Len Deighton, spy fantasy (for example, Ian Fleming and James Leasor) and the more realistic spy fiction (John Le Carré, Deighton, Ted Allbeury).

What makes a good, or bestselling, thriller is anyone’s opinion or guess; there is no set formula though at times it seemed that writers assumed there was. The best thought, if not the last word, on this goes to Jerry Palmer in his 1978 study Thrillers: Genesis and Structure of a Popular Genre: ‘I would say that thriller writing is like cookery: you can give exactly the same ingredients, of the highest quality, to two cooks and one will make something so delicious that you gobble it, the other something that is just food.’

Whatever the quality of the cooking, between 1953 and 1975 Britain’s thrillers certainly fed their readers well. From the dour and austere Fifties, through the fashionable ‘Swinging’ Sixties and into the more severe Seventies, British thriller writers saved the world on a regular basis and in the process achieved fame and fortune, making some of them the pop idols or football stars of their day.

Chapter 2:

THE LAND BEFORE BOND

The Fifties was the decade when Britain had to come to terms with being ordinary. It had emerged from the Second World War as a hero, but an exhausted and almost bankrupt hero. Austerity was Britain’s peculiar reward for surviving WWII unbeaten at the cost of selling her foreign assets and taking on a crippling load of debt to the United States.1

Economically, Britain had been stretched to the point of snapping and it could no longer rely on its Empire for financial support, as it had relied on it for fighting men during the war – a vital contribution without which the outcome may have been different. British overseas assets in 1938 were estimated as being worth £5 billion, but by 1950 had been reduced to less than £0.6 billion and the countries of the Empire had already begun to cut their historic bonds with the mother country. This would not, or should not, have come as a surprise to anyone as independence or ‘home rule’ for many of the colonies, most significantly India, had been suggested or agreed during the war itself. There was also the plain fact that, whilst coping with its debt and a domestic programme creating a welfare state and a National Health Service, Britain could simply not afford the running costs of an Empire any more.

Britain was no longer the global power it had once confidently assumed it always would be and was now running, or perhaps limping, in third place behind the USA and Soviet Russia in any international race. On the home front it struggled simply to get by, a depressing state of affairs for a country which thought it had won the war. Even seven years after the end of hostilities, basic foodstuffs were in short supply (sweets and sugar rationing ending in 1953), there were uncleared bomb sites in many cities and government restrictions on building materials for anything other than housing meant that many buildings including the morale-boosting British pub were at best badly run-down, at worst still bombed-out shells. Until 1952, Britons were required to carry Identity Cards, something perceived (still) as a very un-British, ‘foreign’ affectation unless there was a war on and in 1953, to add insult to injury, the England football team was soundly thrashed 6–3 by Hungary at Wembley Stadium and a new, small family car called a Volkswagen Beetle was being imported from, of all places, Germany.

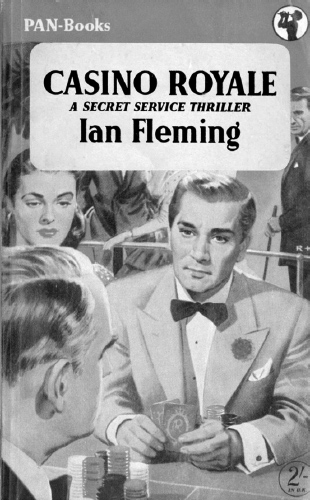

It may have been a scarred country stumbling to find its place in a reshaped world, but it was not all gloom. In 1953 Mount Everest was finally conquered (technically by a New Zealander and a Nepalese, but it counted as a ‘British’ achievement). The number of television sets increased to two-and-a-half million (from around 300,000 in 1950) so that an estimated twenty million proud Britons could watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and two young scientists at Cambridge, James Watson and Francis Crick, discovered something called ‘DNA’. And on 13 April, a thriller called Casino Royale was published.

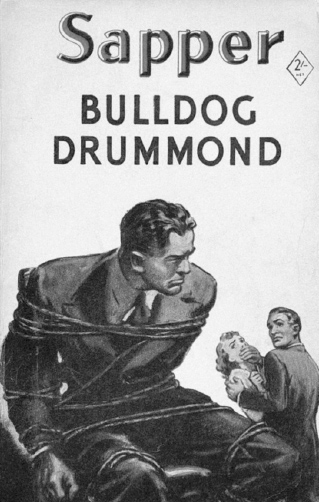

It marked, according to the critic Julian Symons, ‘the renaissance of the spy story’ and it unleashed the character of James Bond on an unsuspecting world. Prior to 1953, new fictional heroes had been compared to Richard Hannay, Bulldog Drummond, or Jonah Mansel, the ‘Terrible Trio of popular fiction between the two wars’ (as created by John Buchan, ‘Sapper’ and Dornford Yates).2 One could add Leslie Charteris’ Simon (the Saint) Templar to this list; but now Bond was the new standard.

Casino Royale, Pan, 1955, illustrated by Roger Hall

Bulldog Drummond, Hodder & Stoughton, 1920

Before Bond, heroes had been upright, square-jawed, patriotic, honourable, and always kind to women, dogs, and horses, though not necessarily in that order. If a John Buchan hero had a gun in his hand it was usually because he was striding through the heather of a Scottish grouse moor – and the same could be said of the heroes of Geoffrey Household’s thrillers of the early Fifties, substituting a Dorset heath for Scotland. Any game that James Bond was hunting with a gun was invariably human and he did not really seem to care too much if an innocent bystander got in the way, and whilst avid fans of E. Phillips Oppenheim and Peter Cheyney would feel right at home with the descriptions of luxury living and thick-eared violence, there was no doubt that Bond was something different.3